In my last post back in June, I introduced a new data structure, the PatchWorkArray, which performs insertions and deletions lazily in an attempt to improve performance over the lifetime of the list. In this post, I'll detail a simple extension to this class which makes it more practically usable and show how it compares with other list implementations over a number of performance tests. A zip file containing all the source code, unit test code, javadoc and a distributable jar file for the classes mentioned in this post are available at: scottlogic-utils-mr.zip.

Making the PatchWorkArray More PracticalAs I mentioned in my previous post, the PatchWorkArray works by maintaining a store of the alterations that have been made to an underlying backing list. In general, the larger the number of alterations, the worse the PatchWorkArray's performance. Although the implementation performs some local optimization, which attempts to minimise the number of alterations, there may be times when it is faster to ensure the list has no alterations prior to performing some operation. For this the fix method is supplied. For example, if you are given a list of indices and you need to return the elements in the list at those indices, as opposed to writing:

public static <T> List<T> getElementsAtIndices(

PatchWorkArray<T> list, List<Integer> indices){

List<T> selectedElements = new LinkedList<T>();

for(int index : indices){

selectedElements.add(list.get(index));

}

return selectedElements;

}It is likely to be more efficient to write:

public static <T> List<T> getElementsAtIndices(

PatchWorkArray<T> list, List<Integer> indices){

List<T> selectedElements = new LinkedList<T>();

if(list.getPerformanceHit() > 10 && indices.size() > 10)

list.fix();

for(int index : indices){

selectedElements.add(list.get(index));

}

return selectedElements;

}Line 4 performs a quick check to see if making a call to fix is likely to have any positive effect on the performance - although it must be said that I picked the values of 10 arbitrarily! The clear problem with this approach however is that making an explicit call to fix is not always possible or indeed desirable. Since it's generally better to write methods so that they are not tied to a concrete implementation of an interface, the above method should really be re-written to have the signature:

public static <T> List<T> getElementsAtIndices(

List<T> list, List<Integer> indices)so without adding some form of type checking hack, you won't be able to call the fix method on the list anyway. To get around this problem, I've written a new simple sub-class of the PatchWorkArray, the AutoFixingPatchWorkArray, which as the name suggests, automatically fixes itself if the number of alterations to its backing list breaches some set limits.

AutoFixingPatchWorkArrayThis class is probably a lot simpler and shorter than you might think since there are only two points within the PatchWorkArray code where the number of alterations to the backing list can increase; in the add and remove methods which take an index as a parameter. So by overriding just these two methods so that they make a call to fix before returning, we are pretty much done. The AutoFixingPatchWorkArray determines whether fix needs to be run by calling its aptly named isFixRequired method - which is non-final and protected and so can be overridden if required. The provided implementation of this method checks whether the list's performance hit (which is essentially the number of alterations to the backing list, and the important metric when it comes to the performance, see the previous post for more details), is more than both a set fixed limit and a set fraction of the total size of the list. The core elements of the source code are given below.

public class AutoFixingPatchWorkArray<T> extends PatchWorkArray<T> {

protected final float maxPerformanceHitFactor;

protected final int minPerformanceHitBeforeFix;

public AutoFixingPatchWorkArray(int initialCapacity,

float maxPerformanceHitFactor, int minPerformanceHitBeforeFix){

super(initialCapacity);

this.minPerformanceHitBeforeFix = minPerformanceHitBeforeFix;

if(maxPerformanceHitFactor < 0 || maxPerformanceHitFactor > 1.0){

throw new IllegalArgumentException(

"The maxPerformanceHitFactor must be between 0 and 1 inclusive.");

}

this.maxPerformanceHitFactor = maxPerformanceHitFactor;

}

@Override

public T remove(int index){

T removed = super.remove(index);

if(isFixRequired())

fix();

return removed;

}

@Override

public void add(int index, T obj){

super.add(index, obj);

if(isFixRequired())

fix();

}

protected boolean isFixRequired(){

int performanceHit = getPerformanceHit();

return (performanceHit >= minPerformanceHitBeforeFix &&

size() * maxPerformanceHitFactor < performanceHit);

}

}It make it easier to use, the AutoFixingPatchWorkArray also has a default constructor that sets minPerformanceHitBeforeFix to 10 and maxPeformanceHitFactor to 0.1 (10%), which, after some testing, seem to be relatively sensible default values.

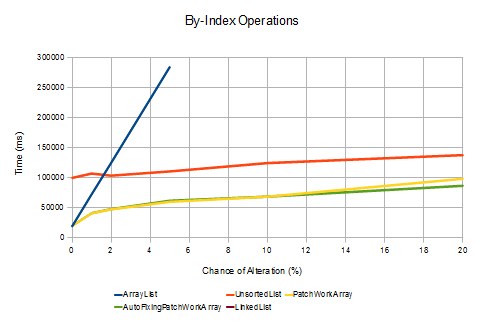

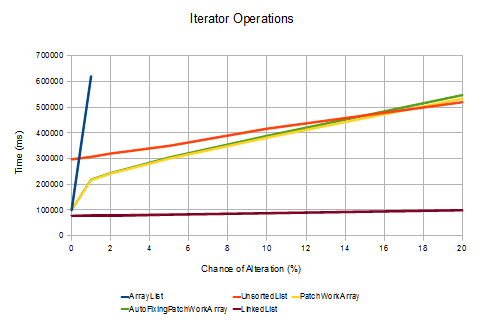

PerformanceTo test the performance of the PatchWorkArray, I set up a simple test rig that allows you to compare the time it takes for different list implementations to perform a series of operations, where the chance that an individual operation alters the state of the list (adds to it, or removes from it) can be set. In general, operations on lists are either performed by accessing the elements via their indices (by-index) or via an iterator. The difference is that an iterator maintains a position in the list, whereas when you perform an operation by index you first need to locate the element in the list - which can take a significant amount of time, depending on the implementation. Due to this, there are two separate test methods - one for each use case.

The "by index" test method looks like this:

private long addRemoveAndGetByIndexPerformanceTest(

List<Integer> listToTest, int numOperations,

int initialSize, double chanceOfAlteration, Random rand){

//initially populate the list..

populateList(initialSize, listToTest);

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

for(int i=0; i < numOperations; i++){

int listSize = listToTest.size();

int nextIndex = ((int) Math.round(rand.nextDouble()*listSize)) % listSize;

double makeAlteration = rand.nextDouble();

if(makeAlteration <= chanceOfAlteration){

double addOrRemove = rand.nextDouble();

if(addOrRemove < 0.5){

listToTest.add(nextIndex, i);

} else {

listToTest.remove(nextIndex);

}

} else {

listToTest.get(nextIndex);

}

}

return System.currentTimeMillis() - startTime;

}This code randomly performs get, remove or add operations on the given list; the probability that add or remove is called is controlled by the given chanceOfAlteration. The iterator based test method is similar, except that operations are performed on the elements of the list as they are presented by the iterator rather than by randomly jumping to a position in the list.

private long iterateThroughAlteratingPerformanceTest(

List<Integer> list, int numIterations,

int initialSize, double chanceOfAlteration, Random random){

//initially populate the list..

populateList(initialSize, list);

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

for(int i=0; i < numIterations; i++){

ListIterator<Integer> itr = list.listIterator();

while(itr.hasNext()){

@SuppressWarnings("unused")

int next = itr.next(); //take the next element out auto-unboxing..

double makeAlteration = random.nextDouble();

if(makeAlteration <= chanceOfAlteration){

double addOrRemove = random.nextDouble();

if(addOrRemove < 0.5){

itr.add(i); //add any old value..

} else {

itr.remove();

}

}

}

}

return System.currentTimeMillis() - startTime;

}The results of running these methods on the PatchWorkArray, the AutoFixingPatchWorkArray (using the default constructor), the UnsortedList and Java's standard ArrayList and LinkedList are given in the charts below. In each case 100,000 operations were performed on lists with 100,000 elements initially, and the times given are the result of running the tests 1,000 times on my work desktop. To make the chart easier to interpret, I've obmitted the results which took too long to process (including all tests involving running the "by index" method on a LinkedList!). I'm always a bit dubious of software performance tests when the person writing the test is the same person writing the thing to be tested, so I've included all the test code in the StandardListPerformanceTests class in the download; so feel free to run them yourself!

The results show, as you'd expect, that data structure choice can have a significant effect on application performance. Whilst the UnsortedList works well in the case that there are many alterations, the LinkedList when used via an iterator and the ArrayList when no alterations are made, the PatchWorkArray offers all-round good performance across all cases tested. Due to the relatively large size of the lists compared to the number of operations, the difference between the PatchWorkArray and AutoFixingPatchWorkArray is negligible. When I tested it over more operations the latter performed better; however, it really depends on how the list is to be used as to which is the most efficient, as there is a trade off between the time it takes to fix the list and the time saved per individual operation when their are fewer alterations to the backing list.

As I mentioned in the previous post, it's likely that with further development the performance of the PatchWorkArray could be improved, even so however, it demonstrates that the effect of lazily performing alterations to a backing list is potentially a useful tool in providing fast data access and manipulation.