Writing software that is concurrent, scalable and fault-tolerant is hard. To achieve concurrency developers have to manage multiple threads, which can be tricky and error-prone. This post looks at how the Actor model makes it easier to write concurrent code. Specifically it renders a Mandelbrot Set using the Akka framework and investigates how Akka can be used with Scala to create highly concurrent and scalable systems.

What is the Actor Model?

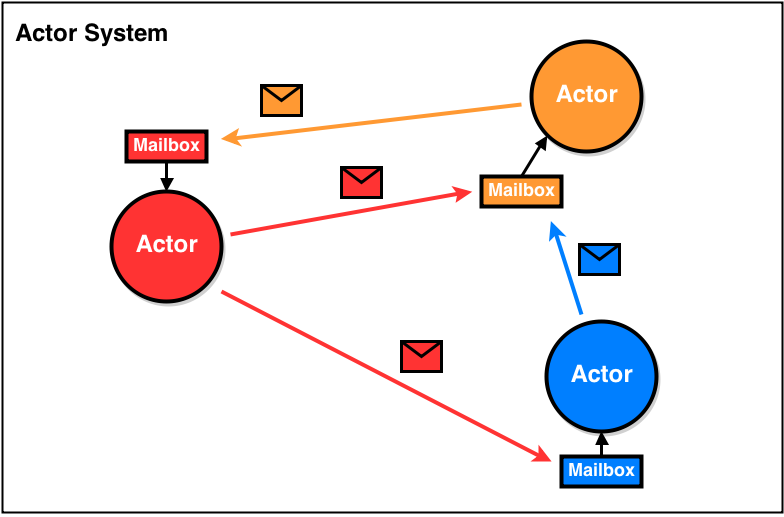

The Actor model allows the developer to write concurrent and distributed systems by abstracting the low-level problems of having to deal with locking and thread management. The model is made up from a set of components known as Actors. They communicate by sending messages, with some content, to one another. There are several key points about how Actors behave: * When a message is received they decide what to do based upon the message type and content. * In addition to normal operations, they can create new Actors or send messages to other Actors. * They each have an address. Messages can only be sent to Actors whose address is known. * They have a mailbox, all messages received go to the mailbox. * Typically, they act upon messages in the order they arrived in the mailbox. * If the mailbox is empty the Actor will handle a new message as soon as it arrives. * Since the Actors can act asynchronously there is no guarantee what order the messages will arrive in.

The diagram below shows multiple Actors in an Actor system communicating through message passing.

There are various implementations of the Actor model. Akka is a framework available for both Java and Scala, in this post I have used it with Scala. Scala used to have its own implementation of the Actor model but this was deprecated in Scala 2.10 in favour of the Akka framework’s implementation.

Implementing the Actor Model using Akka

To demonstrate the Actor model I have looked at the problem of defining which complex numbers lie in the Mandelbrot Set. Specifically, I have used the Escape Time Algorithm to see if each point lies in the set. The algorithm iteratively applies a set of mathematical operations to an input value and terminates when the value reaches a specified threshold or after a maximum number of iterations. The number of iterations performed for each complex number is the value that I have associated with it.

This problem is well suited for the Actor model as it is known as an ‘embarrassingly parallel’ problem. Since the calculations for each individual complex number can be done completely without state and independent of one another, this problem is easy to parallelise. I have split the grid of complex numbers into several ‘horizontal’ segments which can each be calculated concurrently.

I used the Sbt build tool for this Scala project and my build.sbt is as follows:

name := "akka-scala"

version := "1.0"

scalaVersion := "2.11.2"

resolvers ++= Seq(

"Typesafe Repository" at "http://repo.typesafe.com/typesafe/releases/"

)

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"com.typesafe.akka" %% "akka-actor" % "2.3.4"

)

This file defines the project name, project version number, the version of Scala to be compiled against and any dependencies I need. For this project the only dependency is the Akka framework, of which I’m using version 2.3.4.

I can now start creating my Actor model, in which I will use three different Actors:

- Master Actor - keeps track of results for each complex number and will handle the forwarding of segments of work to the workers.

- Worker Actor - performs the necessary calculations for each of the segments of complex numbers.

- Result Handler Actor - handles the result when all points have been calculated.

I have started by creating the following:

object Mandelbrot extends App {

calculate(numWorkers = 4, numSegments = 10)

sealed trait MandelbrotMessage

case object Calculate extends MandelbrotMessage

def calculate(numWorkers: Int, numSegments: Int) {

val system = ActorSystem("MandelbrotSystem")

val resultHandler = system.actorOf(Props[ResultHandler],

name = "resultHandler")

val master = system.actorOf(Props(

new Master(numWorkers, numSegments, resultHandler)),

name = "master")

master ! Calculate

}

}Here I have created an object which extends App so that it is executed when the program is run. The object starts by calling a calculate method with the number of workers and segments to use. numWorkers will become clear later, numSegments is how many ‘horizontal’ segments I have split the grid into. The first thing the calculate method does is create an Actor system, this is a collection of Actors that can share configuration. The method then creates a Result Handler Actor, the address of which is passed into the Master Actor. The final line of the method sends a Calculate message to the Master Actor - this message is used to tell the it to calculate the Mandelbrot Set. Messages in an Akka model should be lightweight and immutable, this makes case objects/classes perfect. I have therefore created a Calculate case object. It extends a trait which will be used for all my messages.

I now add the Master Actor to the Mandelbrot object:

import akka.actor._

import akka.routing.RoundRobinPool

import scala.concurrent.duration._

import scala.collection.mutable

object Mandelbrot extends App {

...

case class Work(start: Int, numYPixels: Int) extends MandelbrotMessage

val canvasWidth: Int = 1000

val canvasHeight: Int = 1000

...

class Master(numWorkers: Int, numSegments: Int, resultHandler: ActorRef)

extends Actor {

var mandelbrot: mutable.Map[(Int, Int), Int] = mutable.Map()

val workerRouter =

context.actorOf(Props[Worker].withRouter(RoundRobinPool(numWorkers)),

name = "workerRouter")

def receive = {

case Calculate =>

val pixelsPerSegment = canvasHeight/numSegments

for (i <- 0 until numSegments)

workerRouter ! Work(i * pixelsPerSegment, pixelsPerSegment)

}

}

}There is a lot going on here so I’ll go through it step by step. The Master Actor is implemented in the Master class which extends Akka’s Actor class. The constant values canvasHeight and canvasWidth are used to define the range of complex numbers I will use.

The Master Actor starts by creating a mutable map, which is used to hold the results for each complex number. Each entry in the map has a tuple as the key (containing the co-ordinates of the point) and the number of iterations it takes to ‘escape’ the algorithm as the value. I have used a mutable map so I can easily add new results as and when they are received.

A round robin router is then created; each time a message is passed to the router it will be forwarded to the next Actor, i.e. if the router contains two Actors the first message it receives will go to the first Actor, the second to the second Actor, the third to the first Actor and so on. numWorkers defines how many Worker Actors are available in the router.

Every Actor in Akka must implement the receive method, this method is called when a message is received. In the Master Actor the message is handled using pattern matching; if the message is a Calculate object then it passes Work messages to the worker router. This is where the problem is parallelised by splitting the complete set of complex numbers into the specified number of segments. Each Work message sent to the worker router states the segment of numbers it should calculate. If the receive method receives a message that is not a Calculate object then it will do nothing and ignore it - in a production environment you would more likely want to throw an exception if this happened.

Next I need to create the Worker Actor:

case class Result(elements: mutable.Map[(Int, Int), Int])

extends MandelbrotMessage

val maxIterations: Int = 1000

...

class Worker extends Actor {

def calculateMandelbrotFor(start: Int, numYPixels: Int):

mutable.Map[(Int, Int), Int] = {

var mandelbrot: mutable.Map[(Int, Int), Int] = mutable.Map()

for (px <- 0 until canvasWidth) {

for (py <- start until start + numYPixels) {

// Convert the pixels to x, y co-ordinates in

// the range x = (-2.5, 1.0), y = (-1.0, 1.0)

val x0: Double = -2.5 + 3.5*(px.toDouble/canvasWidth.toDouble)

val y0: Double = -1 + 2*(py.toDouble/canvasHeight.toDouble)

var x = 0.0

var y = 0.0

var iteration = 0

while (x*x + y*y < 4 && iteration < maxIterations) {

val xTemp = x*x - y*y + x0

y = 2*x*y + y0

x = xTemp

iteration = iteration + 1

}

mandelbrot += ((px, py) -> iteration)

}

}

mandelbrot

}

def receive = {

case Work(start, numYPixels) =>

sender ! Result(calculateMandelbrotFor(start, numYPixels))

}

}This might initially look quite complicated but it isn’t actually doing that much. As with all Actors I need to implement the receive method - if a Work message is received then values are calculated for the complex numbers. The calculation happens in the calculateMandelbrotFor method. Given a start value and the number of values to compute the method calculates the values as defined by the Escape Time Algorithm and returns them in a mutable map.

Once calculated, the results are sent back to the Master Actor. This is done using the sender reference which is always passed with a message in Akka. It is a reference to the sender of the current message. The results are sent using the newly created Result class. The Master Actor can now be updated to handle this message:

case class MandelbrotResult(elements: mutable.Map[(Int, Int), Int],

duration: Duration) extends MandelbrotMessage

...

class Master(numWorkers: Int, numSegments: Int, resultHandler: ActorRef)

extends Actor {

var numResults: Int = 0

val start: Long = System.currentTimeMillis()

...

def receive = {

...

case Result(elements) =>

mandelbrot ++= elements

numResults += 1

if (numResults == numSegments) {

val duration = (System.currentTimeMillis() - start).millis

resultHandler ! MandelbrotResult(mandelbrot, duration)

context.stop(self)

}

}

} Here I have added a new case to the receive method which handles Result messages. The first thing this does is add the new elements to the map. A count of the number of results received is then incremented. Results from all Workers are received once the number of Work messages sent equals the number of Result messages received. When all results have been received the length of time it took for the calculations to be performed is stored. A message is then passed to the Result Handler Actor. This message contains the map of calculated values and the time it took to complete the calculations. At this point the Master Actor is no longer needed so it can be stopped. Stopping an Actor will also stop all of its child Actors, in this case the Worker Actors that it was using.

The final step is to create the Result Handler Actor:

class ResultHandler extends Actor {

def receive = {

case MandelbrotResult(elements, duration) =>

println("completed in %s!".format(duration))

context.system.shutdown()

}

}This is the simplest of the Actors, when it receives a MandelbrotResult message it prints a line in the console displaying the amount of time the computation took. The Actor system is then no longer needed and can be shut down.

The Result Handler Actor has been sent the elements in the Mandelbrot Set but currently does nothing with them. It would be nice if there was some way to visualise the results. I have done this using a JFrame:

import javax.swing.JFrame

import java.awt.{Graphics, Color, Dimension}

import scala.collection.mutable

class MandelbrotDisplay(points: mutable.Map[(Int, Int), Int], height: Int,

width: Int, maxIterations: Int) extends JFrame {

setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE)

setPreferredSize(new Dimension(height, width))

pack

setResizable(false)

setVisible(true)

override def paint(g: Graphics) {

super.paint(g)

var histogram: Array[Int] = new Array[Int](maxIterations)

for(px <- 0 until width) {

for (py <- 0 until height) {

val numIters = points(px,py)

histogram(numIters-1) += 1

}

}

var total = 0

for(i <- 0 until maxIterations) {

total += histogram(i)

}

for(px <- 0 until width) {

for (py <- 0 until height) {

val numIters = points(px,py)

var colorVal = 0.0

for(i <- 0 until numIters) {

colorVal += histogram(i).toFloat / total.toFloat

}

val rgb = Color.HSBtoRGB(0.1f+colorVal.toFloat,

1.0f, colorVal.toFloat*colorVal.toFloat)

g.setColor(new Color(rgb))

g.drawLine(px, py, px, py)

}

}

}

}This algorithm is based on histogram colouring. All it does is extend a JFrame and overrides the paint method. In this implementation each pixel is looped through and given a colour based on the number of iterations it took to ‘escape’ from the algorithm. This can be created by adding one more line to the Result Handler:

class ResultHandler extends Actor {

def receive = {

case MandelbrotResult(elements, duration) =>

println("completed in %s!".format(duration))

context.system.shutdown()

new MandelbrotDisplay(elements, canvasHeight, canvasWidth, maxIterations)

}

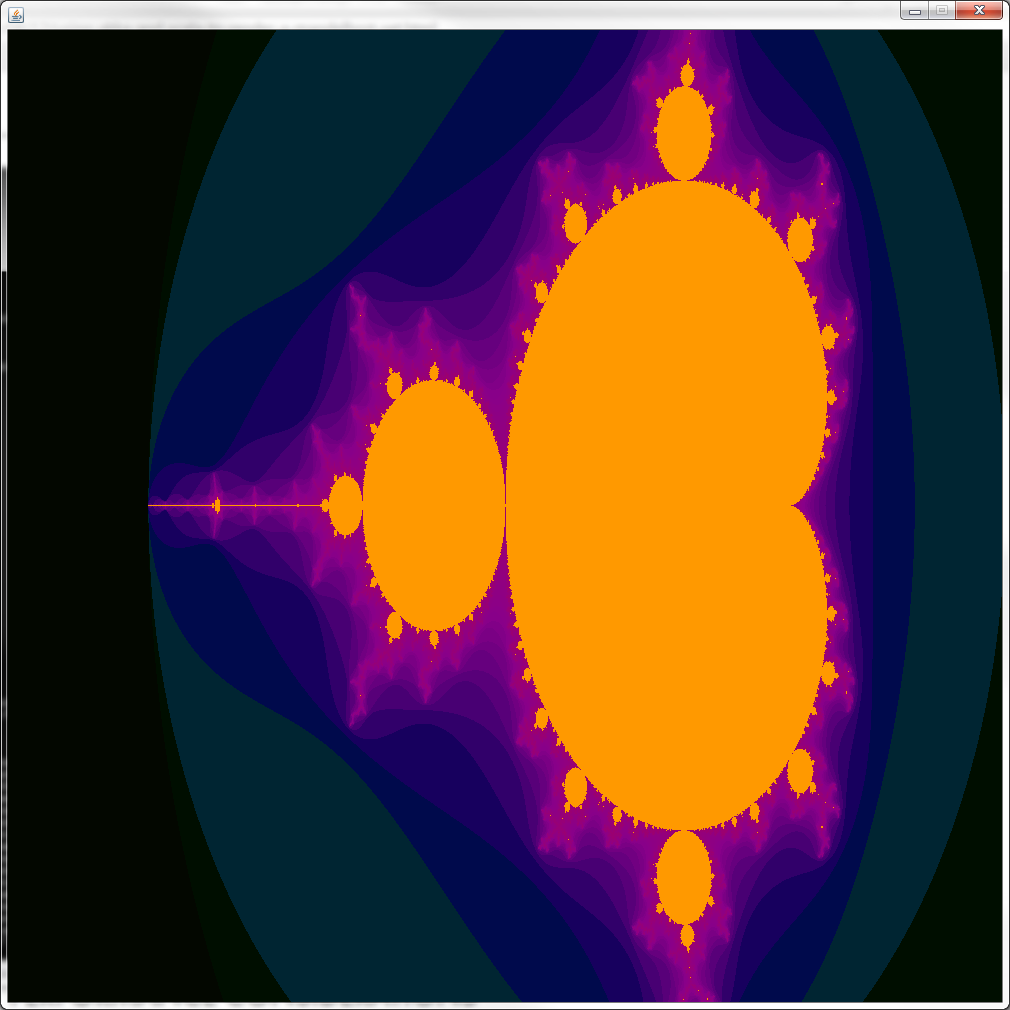

}If I now run the code I see an image similar to the one below, pretty cool! To understand more about what the image shows you should read about Mandelbrot Sets. If you want to see the entirety of my code and try it for yourself you can find it here.

I have now implemented a simple Actor model using the Akka framework and I hope you’ll agree that it was a lot simpler than the alternative of explicitly handling thread management. The workers are the part of the system that act concurrently to calculate the value of points in the set. Here I have used four Worker Actors that work at the same time to calculate values. What do you think will happen if I change the value of the numWorkers parameter in the call to the calculate method?

Performance Considerations

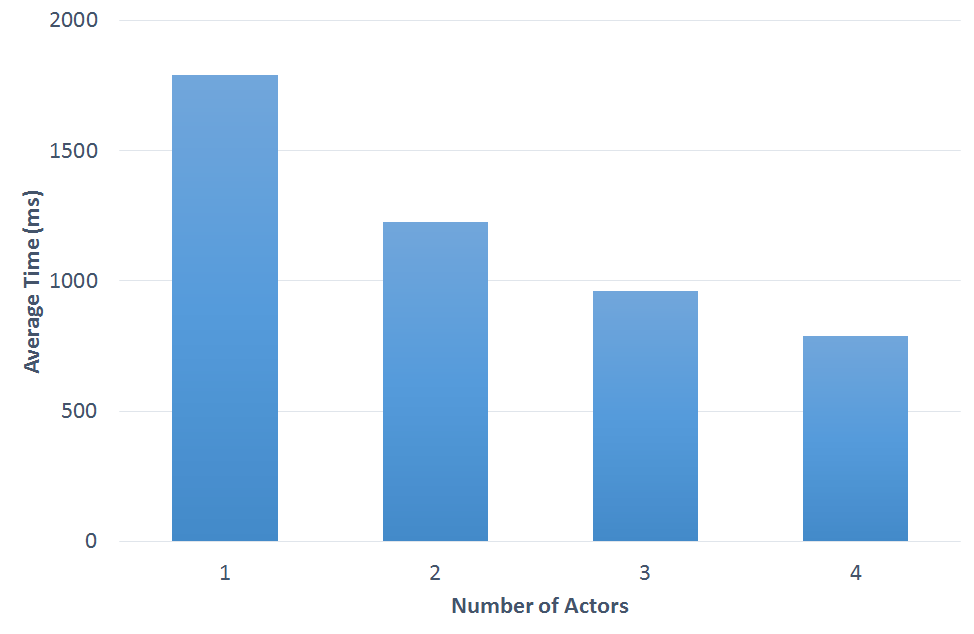

The main advantage of using an Actor model is to easily create highly concurrent and distributed systems, as such you would expect to see a performance benefit from using it. By changing the number of Actors in the router pool in this example I can change the performance of the system. The more Actors in the pool the quicker the calculations will be. I have run the project on a computer with a quad core processor. This means that four Actors is roughly the best performance I can get. Four Actors equates to one thread per core, allowing the core to put all its resources onto that thread. Therefore there is no benefit if I create a pool of eight Actors, as two threads would run on each core, but each thread would have fewer resources and would take longer to calculate.

I executed the program a number of times with one to four Actors in the pool and measured the average time it took for the program to execute. The graph below shows the results. With one Actor the average time was 1790ms, this time was drastically decreased to 788ms when four Actors were used. There is a significant performance improvement each time the number of Actors in the router pool is increased and there was more than a 50% reduction in the execution time by changing from one to four actors in the pool.

In this example I have used Akka’s RoundRobinPool for delegating messages between the Workers. The round robin pool passes messages to each Actor in the pool in turn. This might not provide the best performance or be appropriate, depending on the use case. Akka offers several other routing methods, including:

RandomPool- selects Actors at random to pass the message to.BalancingPool- attempts to distribute work evenly between Actors.SmallestMailboxPool- sends messages to the Actor with the fewest messages in its mailbox.BroadcastPool- The router sends all messages to all Actors in the pool.

When creating an Actor system you should decide which routing method is most appropriate for the situation. It is also possible to create custom routers should none of the routers provided by the framework suit your needs.

Another consideration when using Akka is that of message delivery. There are three basic categories for message delivery; the default, which has been used in this example, is at-most-once delivery. at-most-once delivery means that the message will be sent once and will be received either once, or it will be lost during delivery and will not be received. This is the cheapest message delivery method with the highest performance. The second message delivery method is at-least-once delivery, multiple messages could be sent, such that at least one is delivered - it indeed could be the case that multiple messages are received. The final method has the worst performance - exactly-once delivery. For this method both the sender and receiver need to keep state to check that duplicate messages are neither sent nor received. When designing an Actor model you should decide which delivery method is most suitable for your needs, sometimes the performance trade-off will be necessary to ensure that every message is delivered the correct number of times.

So, Should You Use an Actor Model?

Actor models make concurrent software much easier for developers to write, as the developer does not have to deal with thread management and locking. They can write in simple, high level terms of message passing between Actors and let the framework deal with thread management. This will allow developers to produce correct concurrent software much quicker than was previously possible.

If you have a problem that can be parallelised then I would suggest you consider using an Actor model. The performance benefit can be substantial and the implementation is relatively straightforward. This benefit can be more substantial when used in a production environment when your program is not running on a multi-core processor but on multiple distributed servers.

This post has only scratched the surface of the Actor model and Akka framework but hopefully you have seen their benefits. I would encourage you to try using an Actor model when you next get the chance.