This blog post explores the novel approach taken by the React.js team, where the UI is expressed as a function of the current application state, and re-implements it with Swift.

Introduction

Before getting into the details of the blog post, I want to make something quite clear, I am not trying to port React to Swift, and have no intention of embarking on such an undertaking! Furthermore, this post will not provide a terribly useable UI framework. React is coming to iOS soon, in the form of React Native, and will be the subject of an article I am writing for Ray Wenderlich’s website.

So why am I doing this? And what is this blog post all about then?

React takes a novel and in some respects surprising approach to UI development. The framework is deeply functional and focusses on immutability and reducing complexity. This should cause any Swift developer to take interest!

Hopefully this post will draw your attention to something new and exciting, and perhaps make you view things differently in future? I know that my perspective on UI patterns has changed a lot since I first started learning about React.

Battling UI State

The Swift language features (an expressive closure syntax, structs, let, etc …), have allowed us to minimise mutable application state, which results in simpler, more expressive code.

However, that beauty ends when you encounter the UI!

The problem with user interfaces (in pretty much any technology) is that they are heavyweight. There is a significant cost associated with constructing UIView instances, which is why as the state of the application changes, we update the state of the current views, rather than having immutable view objects which are thrown away and replaced with new ones. This is also why table and collection views recycle cells.

There are a number of ways you can update UI state and keep it synchronised with your model. You can do it manually, by updating the properties of the views directly when your model changes, and responding to use interactions, via delegate or target-action, and updating your model accordingly.

There are slight more elegant methods, that minimise the code required to manage these two flows of data (from model to view and view to model), search as ReactiveCocoa bindings:

searchTextField.rac_textSignal() ~> RAC(viewModel, "searchText")(The above uses a few Swift ‘shims’ over ReactiveCocoa)

Or more recent concepts such as Bond:

textField ->> labelHowever, regardless of the mechanism you use to keep your view synchronised with your model, it will always involve replication of state. One copy in your model, and another copy in your view.

Surely there is a better way.

What if the UI state of your application could be expressed purely and simply as a function of the current application state?

We all love the functional features of Swift, map, filter, reduce and the like - what if we could use these techniques to construct our view as a function of the application state, and not have to worry about shuffling data back and forth between the view and model any more?

That would be really cool … right?!

Building React in Swift

I really like learning about frameworks by looking at how they might be implemented. For example, Tero Parviainen does a great job of introducing AngularJS by creating his own implementation. James Long does the same for React, creating a 200-line framework named ‘bloop’ based on the same principles. James’ blog post was very much the inspiration for the one you are reading now, which re-uses some of his examples.

The goal of this experiment is to allow the UI state to be expressed as a function of the application state. We know that UIKit objects (views, buttons, etc …) are heavyweight, so we need a more lightweight replacement.

A lightweight view

The following enumeration constructs a number of simple, lightweight, view primitives:

enum ReactView: ReactComponent {

case View(CGRect, [ReactComponent])

case Button(CGRect, String, Invocable)

case Text(CGRect, String)

case TextField(CGRect, String, Invocable)

func render() -> ReactView {

return self

}

}Which makes good use of the concept of associated values - originally I implemented the above as structs, but found the enumerations to be much more elegant.

The ReactComponent protocol allows the creation of more complex components that are built using the ReactView enumeration:

protocol ReactComponent {

func render() -> ReactView

}ReactView also adopt this protocol, simply returning self.

Let’s take a look at how a UI can be constructed using the ReactComponent protocol and this ReactView enumeration.

The following is a very simple app, defined as a component, that simply renders the current time:

class TimerApp: NSObject, ReactComponent {

var time = NSDate()

func render() -> ReactView {

let formatter = NSDateFormatter()

formatter.dateFormat = "hh:mm:ss"

return ReactView.View(timerFrame, [

ReactView.Text(textFrame, "\(formatter.stringFromDate(time))")

])

}

}timerFrame and textFrame are CGRect instances defined elsewhere (for clarity)

As promised, the UI state is expressed as a function of the application state, which is in this case the time variable.

Rendering the view

In order to render this component, we need a way of taking this lightweight view an constructing a UIKit view hierarchy. That’s the job of the renderer:

class ReactViewRenderer {

let hostView: UIView

let component: ReactComponent

init(hostView: UIView, component: ReactComponent) {

self.hostView = hostView

self.component = component

render()

}

func render() {

// render the component, providing the current view state

let reactView = component.render()

// convert to a UIKit view

let uiView = createUIKitView(reactView);

// send this the host

for subview in hostView.subviews {

subview.removeFromSuperview()

}

hostView.addSubview(uiView)

}

}The above class takes a component and renders it within a host UIView. The final piece of the puzzle is the createUIKitView function used by the renderer class:

func createUIKitView(virtualView: ReactView) -> UIView {

switch virtualView {

case let .View(frame, children):

let view = UIView(frame: frame)

view.backgroundColor = UIColor(white: 0.0, alpha: 0.1)

for child in children {

view.addSubview(createUIKitView(child.render()))

}

return view

case let .Text(frame, text):

let view = UILabel(frame: frame)

view.text = text

return view

case let .TextField(frame, text, invocable):

// ... more UI Kit construction code ....

}

}The above is pretty self explanatory, the switch statement is used to determine the required UIKit control / view, with the associated properties being copied to their respective properties on the UIKit objects.

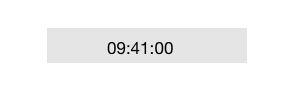

Wiring up the renderer within a view controller results in the following UI:

I’d forgive you for being slightly unimpressed at this point. I’ve simply taken a variable, which never changes, and constructed a UIKit view via some intermediate format.

Bear with me, it gets better!

Updating the view

The app displays the time, but is a pretty useless clock at the moment, time to add some update logic. This is achieved by adding an NSTimer that invokes a tick function every second:

class TimerApp: NSObject, ReactComponent {

var time = NSDate()

override init() {

super.init()

// update the time every second

NSTimer.scheduledTimerWithTimeInterval(1.0, target: self,

selector: "tick", userInfo: nil, repeats: true)

}

func tick() {

time = NSDate()

}

func render() -> ReactView {

let formatter = NSDateFormatter()

formatter.dateFormat = "hh:mm:ss"

return ReactView.View(timerFrame, [

ReactView.Text(textFrame, "\(formatter.stringFromDate(time))")

])

}

}Simple. Our application state is now dynamic, yet the UI is still expressed as a simple function of the current state.

But how do we update the real UI?

One way could be to create some form of notification that informs the renderer that something has changed. But there’s a much easier solution. By adding the following timer to the renderer, the render method is invoked at approximately 60fps:

NSTimer.scheduledTimerWithTimeInterval(0.02, target: self,

selector: "render", userInfo: nil, repeats: true)This repeatedly tears down the UI then re-creates it. As a result the time now updates quite nicely:

If we ignore the rather glaring performance issues, this is a surprisingly elegant solution. There is no need to determine which UI components need to be updated based on the change of application state,removing the need for manual wire-up or bindings. Whilst this is a trivial example, it could be updated to render a much more complex UI with many dynamic parts.

This technique could be used with frameworks like ReactiveCocoa to express an application flow from a network request, through data transformation, right up to the view it constructs.

If you are having a hard time looking beyond the performance implications, I’ll tell you a little more about how React.js works …

With React a virtual DOM is constructed based on the application state. Each time the application state changes the virtual DOM is re-constructed. There then follows a diff (or in React terminology ‘reconciliation’) process, where React works out the most efficient set of changes that need to be applied to the ‘real’ DOM in order to make it match the state of the newly constructed virtual DOM.

I haven’t implemented this in Swift, but I think you will agree that it is entirely possible. The renderer could take the lightweight ReactView hierarchy and diff it with the real UIKit view hierarchy.

This might sound like a crazy an inefficient way to manage the view state, however the React framework, despite early concerns from the community, has proven itself to be remarkably efficient. The creation of the virtual DOM allows React to reason about the most efficient way to update the DOM. You can even use this process for occlusion culling, where off-screen content is not ‘rendered’ to the DOM.

Handling events

The current application doesn’t involve any UI interaction. How does it look when used to construct a more complex application, where the UI is composed of multiple components that allow interaction?

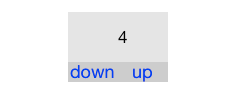

The following code constructs a simple (and ugly) app where a number can be shifted up or down via a couple of buttons:

class CounterApp: ReactComponent {

var count: Int = 0

func changeNumber(newValue: Int) {

count = newValue

_youCannotSeeMe.render()

}

func render() -> ReactView {

return ReactView.View(outerFrame,

[

ReactView.Text(countFrame, "\(count)"),

Toolbar(frame: spinControlFrame, count: count, updateFunc: changeNumber)

])

}

}

struct Toolbar: ReactComponent {

let frame: CGRect

let count: Int

let updateFunc: Int -> ()

func up() {

updateFunc(count + 1)

}

func down() {

updateFunc(count - 1)

}

func render() -> ReactView {

let upHandler = EventHandlerWrapper(target: self, handler: Toolbar.up)

let downHandler = EventHandlerWrapper(target: self, handler: Toolbar.down)

return ReactView.View(frame,

[ReactView.Button(upButtonFrame, "up", upHandler),

ReactView.Button(downButtonFrame, "down", downHandler),

])

}

}Here’s the app in action:

In this more complex example you can see that the CounterApp render function makes use of the ReactView primitives as well as another component, Toolbar. Whilst Toolbar knows the current count, so that it can increment or decrement it, within this component it is a constant.

The EventHandlerWrapper class is from a previous blog post I wrote about eventing in Swift, it provides a mechanism for loosely coupled events without target-action or other UIKit specific concepts.

You might have noticed the line _youCannotSeeMe.render() - as you might have guessed, you weren’t supposed to see that ;-) While the 60fps render-loop works fine for the timer app, it causes issues that interfere with UIButton taps, so I had to add this more manual approach. Please pretend you didn’t see that code!

The simpler app, as well as showing the composition and components, demonstrates the simple process of data flowing down from one component to the next, and events flowing up.

Collections

The previous example still feels a little trivial, how do you render a collection of items? With most UI framework this requires special treatment, concepts such as list views, repeaters, table views crop up everywhere.

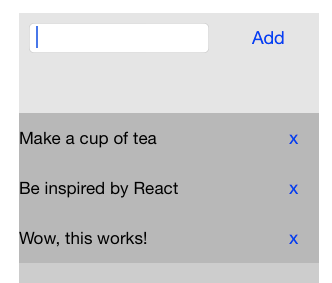

The final example is a simple to-do list app:

The top-level component contains a mutable array of strings, and a variable which represents the current state of the text field at the top of the application:

class ToDoApp: ReactComponent {

var items = ["Make a cup of tea",

"Embrace swift",

"Be inspired by React"]

var newItem = ""

func textChanged(value: String) {

newItem = value

}

func itemDeleted(index: Int) {

items.removeAtIndex(index)

_youCannotSeeMe.render()

}

func addItem() {

items.append(newItem)

_youCannotSeeMe.render()

}

func render() -> ReactView {

let textChangedHandler = EventHandlerWrapper(target: self, handler: ToDoApp.textChanged)

let addItemHandler = EventHandlerWrapper(target: self, handler: ToDoApp.addItem)

return ReactView.View(outerFrame,

[

ReactView.TextField(textFieldFrame, "", textChangedHandler),

ReactView.Button(addFrame, "Add", addItemHandler),

ListItems(frame: listFrame, items: items, deleteAction: itemDeleted)

])

}

}When the Add button is tapped, the text from newItem is added to the to-do list. The items themselves are rendered via the ListItems component shown below:

class ListItems: ReactComponent {

let items: [String]

let frame: CGRect

let deleteAction: (Int) -> ()

init(frame: CGRect, items: [String], deleteAction: (Int) -> ()) {

self.frame = frame

self.items = items

self.deleteAction = deleteAction

}

func rectForIndex(index: Int) -> CGRect {

return CGRect(x: 0, y: 50.0 * CGFloat(index), width: frame.width, height: 50)

}

func render() -> ReactView {

return ReactView.View(frame,

map(enumerate(items)) { (index, item) in

ListItem(frame: self.rectForIndex(index), item: item) {

self.deleteAction(index)

}

})

}

}The constant array of items is rendered using a map operation, with enumerate being used because the frame for each item depends on the index. Each individual item is a ListItem component, which invokes a given function when the delete button is tapped. The render function adds the item index to this ‘event’ which is then passed up to the ToDoApp so that it can perform the required deletion.

Finally the ListItem component is shown below:

class ListItem: ReactComponent {

let item: String

let frame: CGRect

let deleteAction: () -> ()

init(frame: CGRect, item: String, deleteAction: () -> ()) {

self.frame = frame

self.item = item

self.deleteAction = deleteAction

}

func deleteItem() {

deleteAction()

}

func render() -> ReactView {

let addItemHandler = EventHandlerWrapper(target: self, handler: ListItem.deleteItem)

return ReactView.View(frame,

[

ReactView.Text(textFrame, item),

ReactView.Button(buttonFrame, "x", addItemHandler)

])

}

}This simple little example is a good illustration of how data flows down whilst events flow up. There is only a single copy of the applications mutable state, it is not replicated (in a mutable form) within the various components. Once again, the application UI is simply a function of the current application state. Furthermore, regardless of what has changed, we simply re-render the entire application.

Conclusions

Hopefully this blog post has given you an idea of how React works, and why it is so different from the other UI frameworks out there. The functional approach, and minimisation of mutable state, feel quite Swift-like.

And if it has inspired someone to port it to ‘native’ Swift, good luck to you, and I eagerly await the results!

I’ve placed my code from this post on GitHub. Please be warned, it is a concept experimentation, and full of short-cuts, and memory leaks!

Regards, Colin E.

.jpg)