This blog post takes a look at the new ReactiveCocoa 3.0 swift interface, which introduces generics, a pipe-forward operator and an interesting use of curried functions.

This is the first of a couple of blog posts I intend to write about ReactiveCocoa 3 (RC3). The main focus of this post is the Swift Signal class itself, with the next post building on this to show a more complete application.

Introduction

I’ve been a big fan of ReactiveCocoa for a long time, having written a number of articles for Ray Wenderlich’s site, and a few conference presentations on the subject.

When Swift first came out it was possible to bridge the Objective-C ReactiveCocoa API to Swift which results in some significant syntactic improvements to ReactiveCocoa. However with features such as generics, a pure Swift implementation or ReactiveCocoa could be so much better!

Thankfully the ReactiveCocoa team have been working on a brand new Swift API for many months. Just over a week ago they had their first beta release, which is the subject of this blog post.

This post assumes that you are already familiar with ReactiveCocoa, although you certainly don’t have to be an expert!

Creating RC3 Signals

The easiest way to add ReactiveCocoa to a project is to use Carthage, simply create a Cartfile that references RC3:

github "ReactiveCocoa/ReactiveCocoa" "v3.0-beta.1"

Then run carthage update as described in the documentation.

ReactiveCocoa 3.0 contains an all-new Swift API, but also has supported for Objective-C, as described by the detailed changelog. As a result, you’ll find two different types of signal, the Obj-C RACSignal, and the new Swift Signal.

A very important feature of the Swift signal is that it is generic:

class Signal<T, E: ErrorType> {

...

}The type parameter T denotes the type of data associated with the ‘next’ events emitted by the signal, while errors have the type E and must conform to the ErrorType protocol.

Swift signals can be created in a similar fashion to Objective-C signals. Here’s a quick example that creates a signal that emits an event every second:

func createSignal() -> Signal<String, NoError> {

var count = 0

return Signal {

sink in

NSTimer.schedule(repeatInterval: 1.0) { timer in

sendNext(sink, "tick #\(count++)")

}

return nil

}

}(NOTE: The schedule method used above is courtesy of this gist)

The Signal initializer takes a generator, which in this case is supplied as a closure expression. The generator is invoked and passed a sink, which in the above example has the type SinkOf<Event<String, NoError>>. Any events sent to the sink will be emitted by the signal.

The sendNext function takes the value passed as its second argument, constructs an event and passes it to the sink.

Swift signals have a similar memory management model to Obj-C signals, and if clean-up is required when a signal terminates, this should be performed by a disposable which is returned by the closure expression above.

Observing Signals

There are a number of different ways you can observe, or subscribe, to signals. The simplest is to use the observe method, supplying functions or closure expressions for any of the event types you are interested in.

Here’s a simple example where the next event is observed:

let signal = createSignal()

signal.observe(next: { println($0) })Which outputs the following:

tick #0

tick #1

tick #2

tick #3

tick #4As an alternative, you can provide a sink that observes a signal’s events as follows:

createSignal().observe(SinkOf {

event in

switch event {

case let .Next(data):

println(data.unbox)

default:

break

}

})The Event type is an enumeration, with associated values for next and error event types. The SinkOf initialiser in the above code constructs a sink of type SinkOf<Event<String, NoError>>, again a trailing closure expression is passed to the initialiser.

The data that the Event enumeration encapsulates (within next and error events) is boxed, using the LlamaKit Box class which is required due to a Swift language limitation. As a user of RC3 you rarely have to deal with the Event type directly, and the various API methods take care of the boxing / unboxing on your behalf.

The simple code examples above show some of the benefits that Swift brings to ReactiveCocoa. The use of generics for defining signals means that you get type safety when observing events. Furthermore, type inference means that while some of the types you are dealing with are pretty complex, involving nested generics, you don’t have to explicitly declare the generic types.

Transforming Signals

The Swift signal type supports a very similar family of operations to its Obj-C counterpart. However, there is another significant difference in the overall API design.

For a simple map operation, you might expect it to be defined as a method on Signal - in pseudo-code:

class Signal<T, E: ErrorType> {

func map(transform: ...) -> Signal

}However, the map function and all other operations that can be applied to signals are actually free functions:

class Signal<T, E: ErrorType> {

}

func map(signal: Signal, transform: ...) -> SignalUnfortunately by moving from methods to free functions, the interface is no longer fluent. For example a map followed by a filter would look something like this:

let transformedSignal = filter(map(signal, { ... }), { ... })Fortunately ReactiveCocoa has a solution for this problem via the funky looking pipe-forward operator |>, an idea taken from the F# language.

The Swift map operation is actually a curried free function:

public func map<T, U, E>(transform: T -> U)

(signal: Signal<T, E>) -> Signal<U, E> {

}What this means is that on first invocation you supply a transform, which returns a new function that maps from one signal to another using the given transformation.

The pipe forward operator allows you to chain operations that transform a signal to another type (typically another signal).

public func |> <T, E, X>(signal: Signal<T, E>,

transform: Signal<T, E> -> X) -> X {

return transform(signal)

}Putting this into practice, to transform the current signal to emit upper case strings, you can use the curried map function as follows:

let signal = createSignal();

let upperMapping: (Signal<String, NoError>) -> (Signal<String, NoError>) = map({

value in

return value.uppercaseString

})

let newSignal = upperMapping(signal)

newSignal.observe(next: { println($0)})Which results in the following output:

TICK #0

TICK #1

TICK #2

TICK #3

TICK #4Notice that the upperMapping constant has an explicit type of (Signal<String, NoError>) -> (Signal<String, NoError>), this is because there is no way for the compiler to infer the type based on the arguments supplied to the function.

Using pipe forward operator, you can instead transform the signal as follows:

let newSignal = signal |> upperMappingFurthermore, there is also an observe free function that can also be used with pipe forward resulting in the following:

signal

|> upperMapping

|> observe(next: { println($0) })Finally, rather than assigning the result of the curried map function to the upperMapping constant, you can include it within the ‘pipeline’ as follows:

signal

|> map { $0.uppercaseString }

|> observe(next: { println($0) })Notice that you no longer need to inform the compiler of the function type returned by map, it can now infer that from the context.

This is all pretty awesome!

One final observation, you can change the type of data flowing through this pipeline, and the type of the signal. Here’s a quick example:

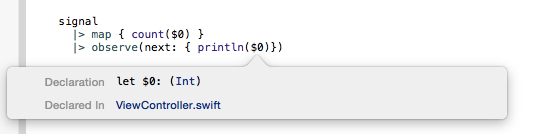

signal

|> map { count($0) }

|> observe(next: { println($0) })The map operation above creates a function that transforms from Signal<String, NoError> to Signal<Int, NoError>.

You can see how the type of the data conveyed by the next event has changed through the pipeline:

The way that pipe forward and these curried functions work together certainly takes some getting your head around. The function signatures are made more complex due to the additional generic parameters associated with Signal.

In order to understand how these all fit together I created a simple example, a string type, with a fluent interface built from free functions and pipe forward. I’ve created a documented playground, available as a gist, which describes it in more detail.

Conclusions

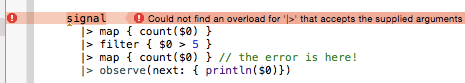

The core concepts of RC3 are the same as RC2, signals that emit events, however the implementation is quite different. While you don’t necessarily need to know how signal operations and pipe forward work, I have this knowledge to be very useful when debugging.

The compilation errors you are faced with when working with RC3 are often misleading and rarely located at the true source of the problem:

It really helps to be able to pull these pipelines apart, so that you can locate the source of the error.

You might also be wondering why build a complex API using curried functions and pipe forward? I had exactly the same thought when I first saw RC3!

One advantage that free functions have over instance methods is that they are not constrained by the rules of inheritance. As an example, the Swift foundation library defines a map function that can be used to transforms anything that conforms to the CollectionType protocol. As a result, you can apply this function to collections that do not have any inheritance relationship (e.g. sets, arrays, dictionaries).

In my next blog post I introduce some of the other new concepts, including signal producers, which are a replacement for cold signals!

Regards, Colin E.