In the last few years prototyping tools, in particular those focusing on animation, have seen tremendous growth. As a designer trying to focus on the busy day-to-day of a project, it’s hard to fit experimentation with new tools into the workflow, and to commit to using new tools for your project.

Fortunately, this past week I had the chance to try out some of the tools that have popped up lately, and get a sense of what they offer and how they can serve the types of projects we do at Scott Logic. To conduct this casual experiment, I came up with a sample design that uses very simple, non-obtrusive animations that were meant to highlight some of the different features/limitations of each tool:

- Manipulating size, position and rotation of shapes

- Control clip size and position of masked shapes

- Manage numerous layers and groups imported from Sketch

- Fine-tune timings for animation triggers

Within this short time-frame, I decided to evaluate 6 tools, and committed to reproducing the general animations in all of these – to properly establish how well they would fit our workflow. The tools I tested were: After Effects, Principle, Atomic.io, Proto.io, Origami Studio and Flinto. The goal was to download each tool, follow some tutorials to learn the basics and create the prototype in less then a day each. Other tools I have previous experience with will also be mentioned along the way.

Flexibility vs Effectiveness

All the tools tested had varying degrees of flexibility and effectiveness, depending on their main goal: to create pixel perfect complex animations, or to quickly prototype an animated interaction.

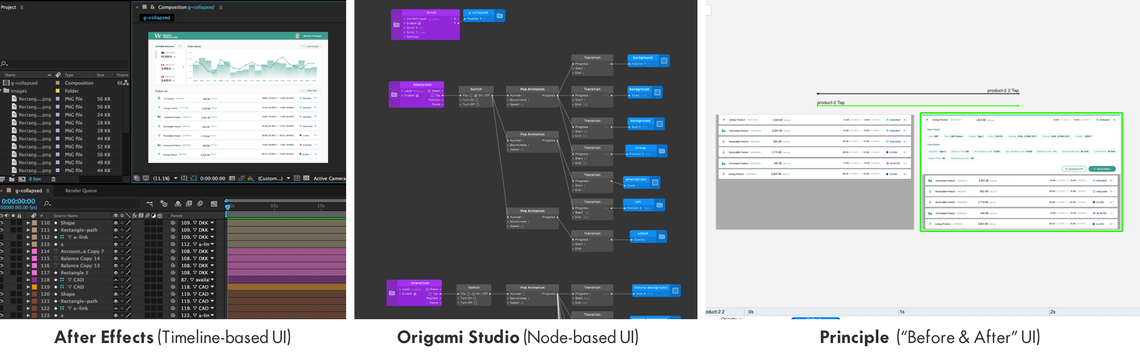

Within the tools designed for flexibility, I would include After Effects and Origami. While boasting completely different animation paradigms, they are both designed to create an animation down to the finest detail, and to that end give you complete control over each animation attribute. After Effects explores animation through the perspective of time, by placing each layer and attribute change to an editable timeline. Origami takes a programmatic approach to animation, by linking attributes and triggers to individual nodes, which combine in tree branches to create the interaction states.

Due to their focus on flexibility, they are also overwhelming and potentially overkill. Hard to learn and to master, they can be great tools in the hands of an animator, but aren’t necessarily designed for rapid prototyping, since they lack automation features and pre-made libraries to speed up the prototyping work. Another tool of this type which I didn’t have time to test is Framer, which combines design tools similar to Sketch, with a code-based approach to creating animation. I would consider any of these tools as ideal for when a specific animation was prototyped and accepted by all important stakeholders, but needs a level of refinement harder to achieve in more simplified tools. This is especially relevant for animated illustrations, loading spinners or splash screens. While After Effects feels more organic to use because of its drag-and-drop style interface, Origami (and in an extreme example Framer) allows you to communicate the design to a developer in an easier way to understand and replicate.

The other group of tools focus primarily on effectiveness: the ability to very quickly produce a good result that conveys the broader strokes of your custom animation, with enough quality to convince your stakeholders. Principle, Proto.io, Atomic.io and Flinto all belong to this group, by approaching animation as a state transition between 2 versions of a design. This means the user designs a “before” and an “after” state for a UI component or screen, and the application builds the animation automatically, without you having to manually plug all the different elements to their animation attributes. This reminded me of Apple’s Keynote (another popular but much more limited tool, built for presentations) and its “Magic Move” transition, which allows you to place objects in one slide, change them in any way in the next slide, and the result is an automatic transformation happening between them.

For prototyping this approach is incredibly powerful, because as a designer you need only design the end states of your animation on Sketch, copy them across to these tools, and create an animation in minutes, with plenty of time spare for further refinements and details. This means that the second group I mentioned inherently felt much more suitable for our workflow – and the rest of this write-up focuses on only those.

Performance is a key factor

As mentioned, the UI concept I used was designed to represent a glimpse at the complexity of the applications we create. Our screens are full of elements, from raw data, to visualisations, imagery, tables and form fields. This means prototyping tools need to not only import all these elements (designed using Sketch), but keep the file structure, namings and relative positions. While all the tested tools with a focus on efficiency had competent import tools, Proto.io flattens every shape and text, requiring you to rebuild any shape you expect to change during the animation. Principle flattens text boxes into images, but keeps shapes as editable vector objects, which at least for the animation I created, was perfectly enough.

As soon as I imported my designs to all these different tools, it was clear that performance was going to be a key factor in this appraisal. Atomic.io and Proto.io are web-based tools, that produce HTML code that runs on any computer and phone, generating links that you can share with stakeholders. While I anticipated this functionality to be a major advantage, the truth is that this web-based nature meant they could not handle the amount of UI elements present on this screen. Not only was it extremely painful and slow to recreate the animations in a sluggish interface, but the output animation was choppy and often buggy – something I wouldn’t share with a client or show to a user.

I believe these tools, especially Atomic.io (which I felt was easier to use, with an interface that feels more intuitive) can be powerful and useful – but only perform well for the purpose of mobile design, where UI elements are fewer by comparison. I could have explored workarounds to this issue, by flattening elements in my Sketch design, but that would mean I would have much less leeway for experimentation.

In contrast both Flinto and Principle, which are native applications for Mac, were extremely snappy and responsive, both in creation mode and preview mode – producing super smooth animations. They felt as good to use as Sketch; moving elements around, editing them, and quickly previewing the result of your actions. They have the downside of not providing a way to easily share the animation with a stakeholder without a Mac computer, but have embedded recording features. Their snappiness combined with the simple-to-use interface meant they were my top picks from this comparison.

Playability as a differentiator

Between Principle and Flinto, the ultimate differentiator is the playability of the interface. For me playability is the ability of an interface to facilitate and encourage the user to go beyond their intentional utilitarian reason for using it and actually start tweaking, experimenting, playing with the tool to achieve unexpected results. Principle was the only tool where I felt I had the time and the means to play with animation, for a few reasons.

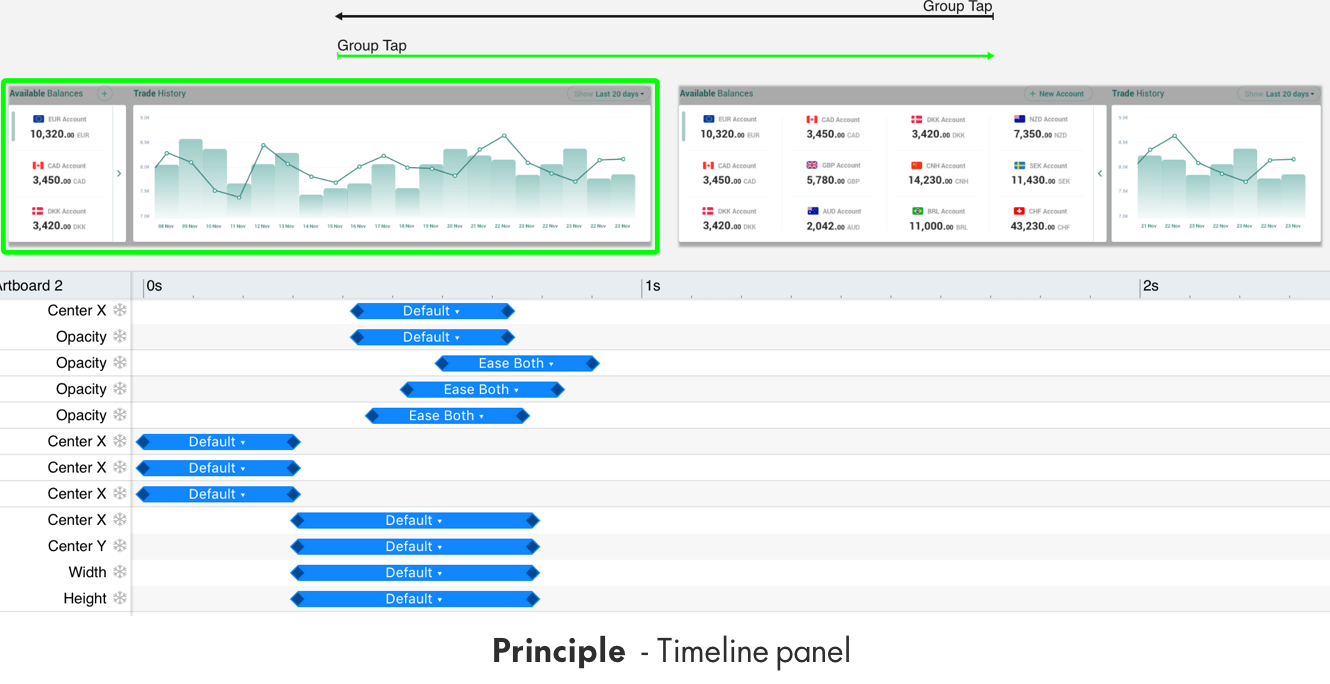

One reason was the super responsive Preview window, which updates live with any change you make, and actually replays automatically when you make a timeline change. The instant feedback it provides is extremely satisfying. Another reason was how it takes inspiration from After Effects by representing the timing of your animations in a timeline interface (Atomic.io and Proto.io do the same but are bogged down by performance issues as mentioned), which makes it easier to create animations with distinct trigger times, animation lengths or easing methods. This tweaking is of course optional, once you’ve quickly prototyped your intention, but adds a lot of power to the tool. Flinto in contrast, forces you to memorise the numeric values (or use a spreadsheet to track them) for these animations, making it harder to experiment.

At the end of the week I was left feeling that Principle has the edge over the competitors, when it comes to the type of work and workflow at Scott Logic, but it was not without some limitations I’d like to see improved. One is improving the synchronicity between layer and object names, which if changed on one side of a state, need to be manually changed on other states for the animation to trigger. Another is improving the timeline interface further, by allowing you to collapse groups, copy animation attributes across elements, or to quickly mirror the entire timeline when performing the reverse interaction.

Conclusion

When I started this week-long adventure I was expecting to find that each application had their strengths & weaknesses and to some extent that is what I found. After Effects and Origami are powerful tools that let you control your animation to the finest detail, to the detriment of efficiency and speed (until you get over their steep learning curves). Atomic.io and Proto.io are tools specifically tailored for mobile design, that let you send out interactive prototypes to stakeholders, to the detriment of performance. Principle and Flinto are easy and efficient tools, that offer a decent level of flexibility while scaling well with complex interfaces.