WebAssembly, despite the name, is a universal runtime that is finding traction on a number of platforms beyond the web. In this blog post I explore just one example, the use of WebAssembly as a smart contract engine on the blockchain. This post looks at the creation of a simple meetup-style event with ticket allocation governed by a smart contract written in JavaScript.

WebAssembly beyond the browser

In 2015 work started on WebAssembly, with engineers from Google, Microsoft, Mozilla and Apple working together to create a new runtime for the web. Just two years later the first version of this runtime was released and implemented in all major browsers. WebAssembly, as the name suggests, is a new low-level language and runtime for the browser that is a compilation target for a wide range of modern programming languages. It provides predictable runtime performance, and is much easier for browsers to decode and compile than JavaScript equivalents.

If you’re new to WebAssembly, I’d thoroughly recommend reading Lin Clark’s cartoon guide, which provides a highly visual explanation of what it is and why we need it!

Despite having “web” in the name, there is nothing web or browser specific about WebAssembly. At runtime it interoperates with a “host” environment that implements the required interfaces; a web browser is just one such host.

Since the launch of WebAssembly in 2017 there has been growing interest in using this technology “outside” of the browser. Its features; a security sandbox, simple instruction set, a lack of built-in I/O operations, language and vendor agnostic have resulted in it being used as a lightweight runtime for cloud functions, an execution engine for smart contracts and even as a standalone runtime.

There are also a growing number of specifications and industry groups looking to extend the capabilities of WebAssembly outside of the browser. Most notable are the WebAssembly System Interface (WASI), that is creating a standard system-level interface, and the recently launched Bytecode Alliance, which has a broad goal of creating a “secure-by-default WebAssembly ecosystem for all platforms”.

There is clearly much to explore! In this blog post I’m going to take a closer look at just one of these out-of-browser use cases, WebAssembly as a smart contracts engine for the blockchain.

A brief blockchain primer

if you’re up to speed on blockchain and smart contracts, feel free to skip this section!

Blockchain was invented as the underlying distributed ledger technology that forms the foundation of Bitcoin. Through a combination of cryptography and a consensus mechanism know as “proof of work”, it is possible for transactions to be processed, and written to a shared immutable ledger, without the need for a trusted authority or central server. The Bitcoin network encodes and executes transactions using a simple scripting language. This language is limited and intentionally not Turing-complete, lacking loops for example, making it deterministic and ‘safe’.

Following the early success of Bitcoin, the Ethereum network was launched in 2014. It is based around a similar set of core concepts, a decentralised, distributed ledger, but with significantly enhanced computing capabilities. With Ethereum, developers can write distributed apps (dApps), which are composed of smart contracts that are deployed to the blockchain network. These contracts are written in Solidity, an object oriented language that was designed specifically for contract authoring, and are executed by the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) that runs on the nodes within the network.

Personally I think Ethereum has more in common with cloud computing than it does with Bitcoin, however, in this case the cloud is not run or controlled by a single company (e.g. Amazon, Microsoft, Google). Instead it is run by the people around the world who operate nodes, and is controlled by the algorithms that govern the operation of the blockchain.

There is of course no such thing as a free lunch, and people who run Ethereum nodes do need to be compensated. This is why Ethereum has its own currency called Ether. Executing smart contracts consumes ‘gas’ which has to be paid for with Ether (similar to the way that executing cloud functions on AWS is paid for with dollars).

So what does all of this have to do with WebAssembly? Good question!

WebAssembly on the blockchain

Ethereum has faced a number of technical challenges and is struggling to scale as adoption increases. As a result, the network has become quite slow, with transaction times running from a few seconds to minutes. It has also become very costly - orders of magnitude more than AWS.

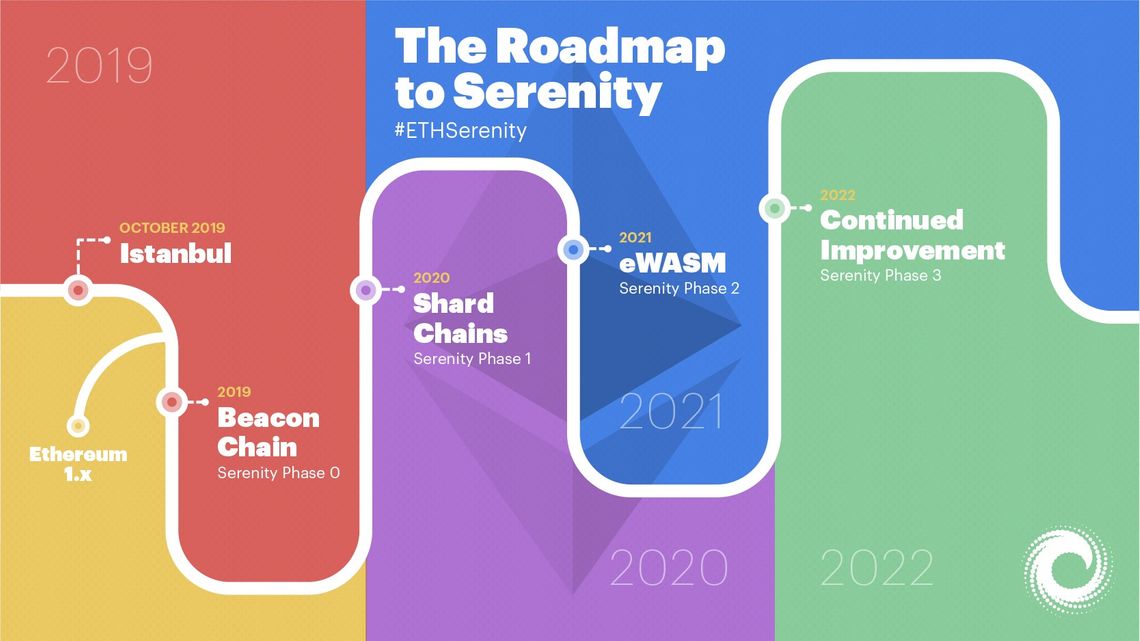

The Ethereum team has a v2.0 roadmap which introduces a number of significant architectural changes that tackle these issues:

Over the next few years the Ethereum team are planning to move to proof-of-stake consensus (as an alternative to the costly proof-of-work), and will introduce sharding - both of which are intended to make the network faster and cheaper. The final thing they want to do is remove the dependency on Solidity and replace their current virtual machine (EVM). With the Solidity programming language numeric types are 256-bit, which at runtime require multiple 32/64 bit operations on the target CPU.

WebAssembly has emerged as a strong candidate replacement for the current EVM. Its host independence, security sandbox and overall simplicity make it an ideal runtime for smart contracts. Furthermore, it also allows the development of contracts in a wide range of modern programming languages (Rust, C++, JavaScript). The Ethereum team have been trialling a WebAssembly-based contract engine, called eWASM, and plan to go live with it at some point in 2021.

Ethereum isn’t the only blockchain company investigating WebAssembly; there are a whole host of others betting on this technology, including Perlin, Parity, NEAR, Tron, EOS, U°OS, Spacemesh and many more - it appears to have become the de-facto standard for building a new blockchain.

Writing a ‘hello world’ smart contract

I wanted to have a go at writing a WebAssembly smart contract, so surveyed the various blockchain implementations to find one that was relatively easy to get started with. After trying out a few different options, I eventually settled on the NEAR Protocol, which I found has the best developer experience, with a hosted testnet, online tools for managing wallets, and an online playground. Furthermore, it has very good support for both Rust and AssemblyScript.

NEAR uses proof-of-stake for consensus and sharding to improve performance, as described in their Nightshade white paper - an interesting read if you want to dig into some of the technical details of how it all works.

Let’s take a look at the process of writing a simple “hello world” smart contract …

Wallet account creation

The deployment and execution of smart contracts and state persistence all costs ‘money’, which is why the very first step of development is the creation of a wallet account. The NEAR network has an online wallet that allows you to create accounts within their test network. To sign up all you need to do is pick a unique username. Once created, your account is funded with 10Ⓝ (i.e. 10 NEAR tokens - the unit of currency for the blockchain), you are also provided with the public and private keys for managing the account.

The NEAR CLI is the primary tool for interacting with the NEAR network, the next step is to install the CLI and login using your wallet account:

$ npm install -g near-shell

$ near login

...

The final step before you can get started with writing some code is to create and fund an account for your smart contract.

$ near create_account hello-world --masterAccount my-wallet-account

Account hello-world for network "default" was created.

$ near state hello-world

Account hello-world

{

amount: '1000000000000000000',

code_hash: '11111111111111111111111111111111',

locked: '0',

storage_paid_at: 1788914,

storage_usage: 182

}

The above has created an account, funding it from my test wallet.

An AssemblyScript smart contract

With NEAR you can write smart contracts in either Rust or AssemblyScript. WebAssembly doesn’t have JavaScript support (the lack of static typing and garbage collection are a challenge), however, it does support AssemblyScript, which is a subset of TypeScript (i.e. JavaScript with types).

Here’s a very simple AssemblyScript smart contract that returns the “hello world” string:

export function helloWorld(): string {

return "hello world";

}

And here is a suitable package.json file with the required dependencies:

{

"name": "smart-contract-hello-world",

"version": "0.0.1",

"dependencies": {

"near-runtime-ts": "nearprotocol/near-runtime-ts"

},

"devDependencies": {

"assemblyscript": "^0.8.1",

"near-shell": "nearprotocol/near-shell"

}

}

This includes assemblyscript which provides the WebAssembly compiler, near-shell which adds a few required compilation utilities, and near-runtime-ts which has additional AssemblyScript code which is required for your contract to communicate with the underlying blockchain.

You can compile smart contracts using a simple compile function from the shell:

const nearUtils = require("near-shell/gulp-utils");

nearUtils.compile("./assembly/main.ts", "./out/main.wasm", () => {});

NOTE: you don’t need Gulp in order to build NEAR smart contracts, I’ve raised an issue with a few suggestion around simplifying this process.

Executing the above via creates a ~9 Kbyte wasm file.

Finally, the NEAR CLI can be used to deploy this wasm file to the network:

$ near deploy --contractName hello-world

Starting deployment. Account id: hello-world,

node: https://rpc.nearprotocol.com, file: ./out/main.wasm

Invoking smart contract methods

NEAR has a JavaScript SDK, nearlib, for interacting with the blockchain network. The following example uses this SDK to connect to the network, then load and interact with the “hello-world” smart contract:

// the configuration required to connect to the network

const nearConfig = {

nodeUrl: "https://rpc.nearprotocol.com",

deps: { keyStore: new nearlib.keyStores.BrowserLocalStorageKeyStore() }

};

// connect to the near network

const near = await nearlib.connect(nearConfig);

// load the smart contract

const contract = await near.loadContract("hello-world", {

viewMethods: ["helloWorld"],

changeMethods: []

});

// invoke the smart contract

const greeting = await contract.helloWorld();

console.log(greeting);

Executing the above code results in the “hello world” greeting being written to the console.

Storing state on the blockchain

Smart contracts can also store state, which is recorded within the blockchain. We’ll demonstrate this by modifying the “hello world” smart contract to record the number of times it has been invoked.

The NEAR runtime provides a key-value store, where you can persist objects of type string, bytes, or u64. The example below stores a u64 value with the key count:

import { storage } from "near-runtime-ts";

export function helloWorld(): string {

const greetingCount: u64 = storage.getPrimitive<u64>("count", 0);

storage.set<u64>("count", greetingCount + 1);

return "hello world " + greetingCount.toString();

}

The contract now effects the state of the blockchain, and is termed a ‘change method’. In order to execute this method from the client, using nearlib, the user must be logged in to a valid wallet account:

// if a wallet account is not present, request sign in

walletAccount = new nearlib.WalletAccount(near);

if (!walletAccount.getAccountId()) {

walletAccount.requestSignIn("hello-world", "Hello World");

}

// load the contract

const contract = await near.loadContract("hello-world", {

viewMethods: [],

changeMethods: ["helloWorld"],

sender: walletAccount.getAccountId()

});

// invoke the smart contract

const greeting = await contract.helloWorld();

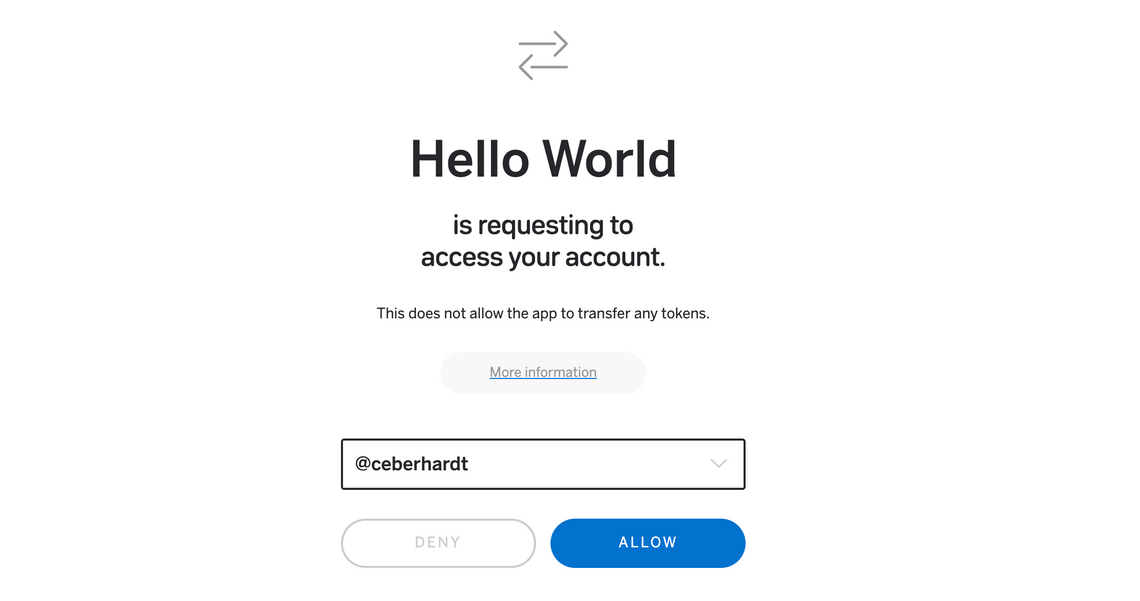

The requestSignIn redirects to the wallet application, allowing the smart contract to request access to your wallet account:

Once access is granted, you are redirected back to the hello world app, where the contract is invoked, returning the greeting with the accompanying invocation count, i.e. hello world 0, hello world 1, …

There’re quite a lot going on here so we’ll review in a bit more detail.

The first thing to note is that you are charged for usage of the network, with charges incurred for various things including contract deployment, storage, contract execution among other things. You can determine the current account balance of a contract via the near state command:

$ near state hello-world

Account hello-world

{

amount: '999999999977548614',

code_hash: '9mfQA5pUKDmH5g3Emi6yqanWXyahLEuauvZEXFZYSNhj',

locked: '0',

storage_paid_at: 1759774,

storage_usage: 12216

}

Note, on the testnet the contract balance, in the amount property, is somewhat arbitrary. However, if you redeploy or execute the contract you will notice that this figure goes down. Also, you can top-up a contract using the near send command to transfer balance from one account to another.

On deployment the contract is distributed across all the nodes within the network (or a network shard). When you execute a ‘change method’ all of the nodes in the network execute the contract to determine the new state and the return value. The proof-of-stake consensus algorithm ensures that that all nodes are in agreement, and a new block is added to the chain.

You can view the blockchain via the online explorer, where you should be able to locate the block that records the transaction which resulted from the contract execution.

You might notice that change methods are slower to return than view methods, this is because change methods result in changes to the state of the blockchain, and that state change must be recorded in a block. With the testnet explorer you can see that a new block is added each second, regardless of whether any transactions occur.

Creating an online meetup group

I wanted to try and create a more meaningful smart contract than a simple counter app. It just so happened that I was due to do a talk at the FinJS conference on WebAssembly ‘out of the browser’. I thought it would be fun to create a spoof meetup, called FinWASM, where the signup process was managed by smart contracts!

Here’s the smart contract code, that allocates a total of 50 tickets, allowing people (who have a NEAR wallet account) to sign up and obtain a ticket:

import { context, PersistentVector } from "near-runtime-ts";

let tickets = new PersistentVector<string>("m");

const TOTAL_TICKET_COUNT = 50;

export function getRemainingTicketCount(): i32 {

return TOTAL_TICKET_COUNT - tickets.length;

}

export function hasSignedUp(): boolean {

for (let i = 0; i < tickets.length; i++) {

if (tickets[i] == context.sender) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

export function signUp(): string {

if (hasSignedUp()) {

return "already_signed_up";

}

if (getRemainingTicketCount() === 0) {

return "event_sold_out";

}

tickets.push(context.sender);

return "success";

}

This contract uses the PersistentVector which allows storage of arrays, other than that, it’s all pretty simple JavaScript (or AssemblyScript) code.

I’ll not show the client-side JavaScript code that interacts with this contract, it’s all very straightforward. If you want to see it in action, the FinWASM event website is online, feel free to sign up!

All the code for this demo is can be found on GitHub.

Conclusions

WebAssembly is starting to gain traction in a number of interesting application areas beyond the browser, I personally think that smart contract development is one of the most interesting. This is a world that is alien to most of us, but perhaps through the broadened language support provided by WebAssembly, more of us can evaluate this technology?

Finally, while my FinWASM meetup website started as a bit of a joke, I soon came to realised that it is actually a perfectly valid and quite sensible use of blockchain. As the contract author, I define the rules for how the event ‘tickets’ are managed, with 50 allocated up-front. Once deployed to the blockchain I am unable to change these rules - I cannot withdraw tickets or decide to give them all to my friends. The system is fair and the rules cannot be changed, even by the contract author.

Smart contracts really are a fascinating and little-used concept. I’d love to see more research and experimentation in this area.