In my first post, I set out why I think we should be Testing with Intent. I set out that, if we focus our tests on the intentions of users, we can improve our test suites and start to tackle accessibility. To keep the content accessible to everyone, I chose to not include anything technical. Now, in this post, I’m going to look at the same subject but through a technical lens.

The essence of this whole approach to testing can be boiled down to one simple golden rule: “Wherever possible, use queryByRole”. We’ll take a look at what we mean by this rule, and start to unpack its consequences.

Those consequences themselves are far reaching. The rule will help direct you to write better tests. The rule will directly improve your web app’s accessibility. The rule will help your team to upskill in accessibility. It’s simple, but it’s powerful.

So, adopting these principles is win-win for a team. With one technique, with one investment, you get better tests, and you get the bonus of tackling accessibility. But how does it work?

What is Testing with Intent?

Testing with Intent is a testing philosophy that is closely related to the Guiding Principles of Testing Library. At a high level, it can be summarised by the following statement:

The more your tests resemble the way your software is used, the more confidence they can give you.

— Kent C. Dodds 🌌 (@kentcdodds) March 23, 2018

When Testing with Intent, we test from the perspective of a user who intends to do something in our system. You might think of this as similar to writing user stories from the perspective of the user. Consider this illustrative example of a user story:

As a user, I want to be able to log out of the system by clicking my avatar and selecting “Log out” from the displayed dropdown menu.

In Testing with Intent, we approach validating a premise within a test in a similar way. To continue this example, consider how to validate the above story. One of our tests would need to go through the very same steps that a user would take to log out. That is to say the test would locate the avatar on the page, click to open the menu, and click the logout option. While this is a straightforward example, the same principles can be applied to more complex test cases.

We’re also not only looking to test the positive outcome. In Testing with Intent, we want to validate that the user was able to realise their intended outcome. We should also validate that there were no nasty side-effects along the way.

Testing with Intent is a subtle yet powerful paradigm shift. A shift away from writing tests that are based on the way we structure code. A shift towards testing based on the way the app is actually used. A shift away from testing the technical implementation details of the software. A shift towards capturing a user’s intention within the test itself.

There are lots of avenues to explore around the awesome impact of Testing with Intent on testing. For this post, I’ll look at Testing with Intent in web frontend automation testing, which is where Testing Library excels.

Meet Testing Library

My journey with Testing with Intent started last year, when I started a new project. My lead, Jim Light, enthusiastically introduced me to Testing Library. Testing Library describes themselves as “a family of packages that helps you test UI components in a user-centric way”. And, their Guiding Principles opens with that same statement from Kent C Dodds above:

The more your tests resemble the way your software is used, the more confidence they can give you.

Have you ever experienced a lightbulb moment when suddenly everything just falls into place? That happened to me here. I’ve always found testing UIs to be cumbersome. I’ve found unit testing every component to be really laborious. It never seemed to offer the rewards to justify the effort. But I also love the confidence that you can get from good automation testing. So, I’ve lived in this uneasy place where I hadn’t found my groove with frontend testing. Testing Library changed all that.

I learnt from Jim. I read the docs. I started implementing tests. It just all made sense. Finally, here was a way of writing the right tests. The tests that give me the confidence that I wanted without costing me hours of tedious work.

Over the course of the project Jim and I discussed lots of aspects of this approach. Those discussions eventually led to this series of blog posts. We both agreed that the ideas here apply irrespective of whether you use Testing Library; Testing with Intent is a way of approaching testing. But, Testing Library provides a set of tools that makes Testing with Intent much more straightforward in frontends. It’s much easier to capture the intentions of a user when you have tools that help you simulate a user interacting with a system. Because of this, Testing Library is a great pairing for this testing approach, and I’ll focus the rest of this post on that pairing.

While explaining how this works, I’ll focus on automated integration tests, although Testing Library is actually broader in scope. To be clear, these tests are broader than unit tests as they are testing a slice of the app’s functionality. These tests can also be run as part of a build pipeline, including as part of automated PR checks.

So how do we go about using Testing Library to write tests?

The Golden Rule: Wherever possible, use queryByRole

In our automated tests, we need a way to identify the elements on the page that are relevant to the test case in hand. For example, if we want to click a submit button, we need a way of identifying that button in our test before clicking it. Testing Library solves this problem with a collection of helper functions called queries. Queries help us in our search for the relevant elements.

When you have a range of queries available, the question that follows is, “Which query should I use?” Testing Library has some great guidance about how to select the right query for the job. It sets out the queries in a prioritised order. However, I’ve gone a step further and boiled that list down into a single golden rule: “Wherever possible, use queryByRole”. If there’s one take away from this post, this is it. Following this rule is powerful. By following it, you create some really positive consequences.

Some might say this rule is a little crude; Testing Library included a priority list for a reason. But, I think there’s a power to following the rule. So, I’m going to unpack how queryByRole works, and why it’s powerful. But before that, it’s about time we see an actual test case!

Show me some code!

Okay, time for an example test using Testing Library. For this, consider the following acceptance criteria of a user story:

When a user clicks the ‘Dashboards’ link in the app’s navbar, they are navigated to the ‘My Dashboards’ page.

Here’s that acceptance criteria written out as a test case:

describe('When a user clicks the Dashboards link in the App Navigation', () => {

it('should display the My Dashboards page', async () => {

// This is a library method to render the app for testing

render(<App />);

// We identify our Dashboards link

const appNavContainer = screen.getByRole('navigation', { name: 'App' });

const dashboardsLink = within(appNavContainer).getByRole('link', { name: 'Dashboards' });

// We use the user-event library to simulate user interactions

userEvent.click(dashboardsLink);

// By convention, our document has a single h1 element that identifies which page we are on.

// So, we wait for navigation, after which the dashboards heading should appear.

// Otherwise the test fails.

const dashboardPageHeading = await screen.findByRole('heading', { level: 1, name: 'My Dashboards' });

expect(dashboardPageHeading).toBeInTheDocument();

});

it('should display the current users Dashboards', async () => {

// ... etc ...

Hopefully, you’ve found this code fairly intuitive to read. There’s a couple of key qualities for tests in this style that I’d like to highlight.

First of all, you’ll see that I’m sticking to my principles and always following the golden rule. I’m using queryByRole, either getByRole or findByRole in this test case.

And secondly, isn’t it simple? Sure, the tests require some extra setup that I haven’t shown. We have a test harness that would help us to mock out parts of the application. That’s always necessary for integration tests. But the test cases themselves really do read like this. They’re simple, and they read like a user interacting with the system.

This brings us nicely back to what I mean when I say that we are testing with User Intent.

Testing with Intent: working with user intentions

To explain this, I need you to put yourself in the shoes of the user in our acceptance criteria:

When a user clicks the ‘Dashboards’ link in the app’s navbar, they are navigated to the ‘My Dashboards’ page.

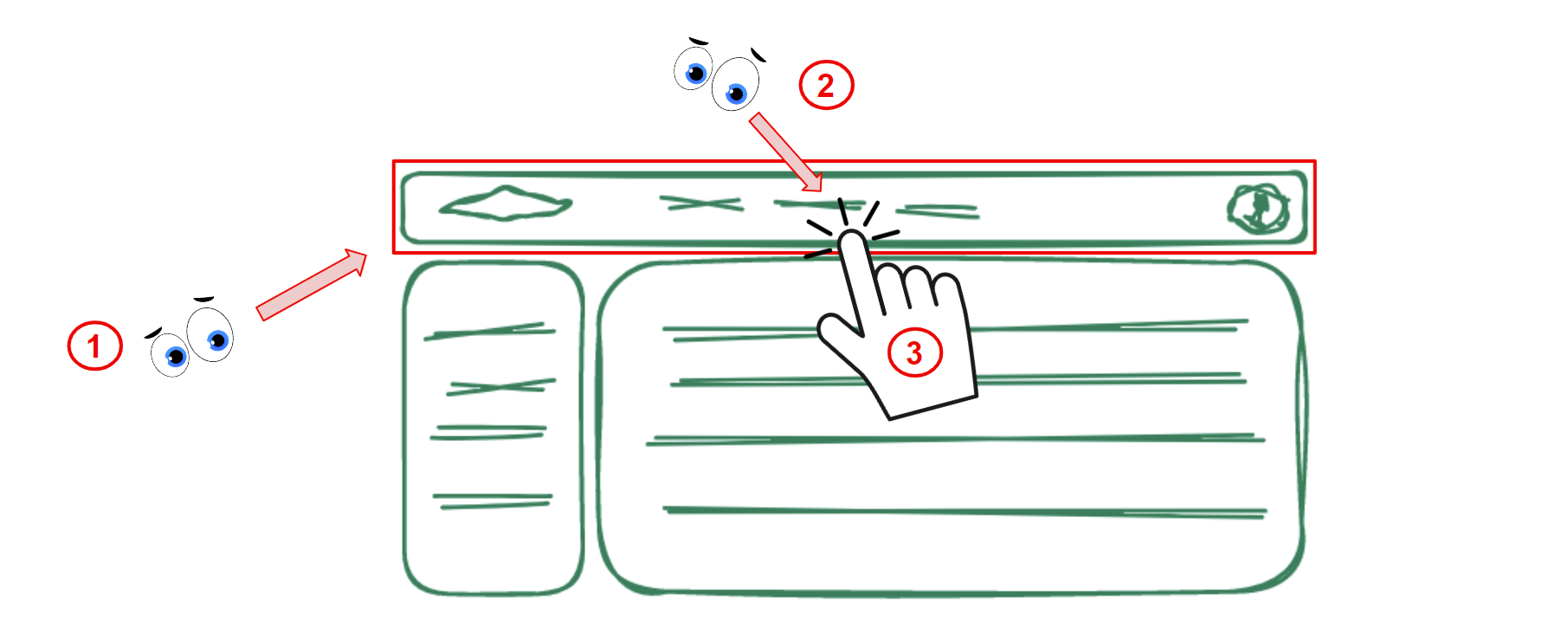

How would you do this? This question isn’t as silly as it sounds. We, as citizens of the internet, have shared Mental Models about the way web pages work. Certain things have a “proper” place. In this example, we generally expect a website’s navigation to be in a bar at the top of the page.

So, if we think of a someone who intends to click the “Dashboards” link, almost every user will:

- Look to the top of the page, where they expect the navigation bar to be

- Within the navigation bar, scan the available links to find the relevant one

- Click it

- Wait for the new page to load

If you go back and look through the test case above, you’ll see that these steps match up exactly with the steps that are coded into the test. This is by design and is exactly what I mean when I talk about Testing with Intent.

This also lives up to the Guiding Principles of Testing Library:

The more your tests resemble the way your software is used, the more confidence they can give you.

Testing in this style is great for our confidence in the product we are shipping. We are actually testing the way we intend a user to interact with the system.

But why is this great for our test confidence? To dig into that we need to consider when we want our tests to fail.

We want tests that fail for the right reasons

The whole reason we spend lots of time writing tests is the confidence they give us. We need to feel confident that our carefully crafted code works. We need to feel confident that nothing is going to blow up when we ship the shiny new version of our app. We need to feel confident that the only changes our users experience are the fancy new features we’ve added.

This is key: our application is only broken if something is broken for our users. Our tests should reflect this; our test failures should indicate that something unexpected has changed for our users. A test failure should say that the way a user experiences the app has changed.

We write our tests to make us feel confident that this is the case. We need to ensure that our app’s existing functionality still works. We need to ensure that rules that define our business logic function correctly. We need to ensure that the user experience is consistent. We need to ensure that our acceptance criteria are all being still met.

Now the opposite of the above is also true. We should never have a test failure if nothing has broken for our users. Have you ever been frustrated by a test that failed due to some unrelated technical change? It’s annoying, and it also costs a lot of time to fix all these incorrectly broken tests.

But this shouldn’t happen. You should be free to dream up whatever whacky technical changes are needed without generating test failures. To go to a theoretical extreme, you should even be able to rewrite your application from Angular to React, with only very minimal changes to your actual test cases.

Our tests are failing for the right reasons

Okay, so coming back to the test case we looked at above. When will it fail?

it('should display the My Dashboards page', async () => {

render(<App />);

const appNavContainer = screen.getByRole('navigation', { name: 'App' });

const dashboardsLink = within(appNavContainer).getByRole('link', { name: 'Dashboards' });

userEvent.click(dashboardsLink);

const dashboardPageHeading = await screen.findByRole('heading', { level: 1, name: 'My Dashboards' });

expect(dashboardPageHeading).toBeInTheDocument();

});

If we work through the test, we can see that our test suite is going to throw an error, and so cause a failure, when:

- We don’t have an

appNavContainer. Our navigation bar has gone missing! - We don’t have a

dashboardsLinkin ourappNavContainer. The user has lost the option to navigate to the dashboards page - Clicking the

dashboardsLinkdoes not cause thedashboardPageHeadingto appear on screen. Something has gone wrong with navigating to the correct page.

That’s it! There’s no other failure conditions. These failure reasons are exactly what we are looking for. In each case, something has gone very wrong for our users. I wouldn’t want to ship the code if any of those cases failed.

Sure, this doesn’t get rid of test failures entirely. You can break the test by doing something like removing the dashboards link. Perhaps you need to move the link to a different menu. But doing so would invalidate an existing acceptance criteria. If we invalidate an acceptance criteria, we should be changing a test; the expected functionality has changed.

Great, our test is giving us the sorts of failures we want. But there’s actually a bit more depth here. Why are we getting the failures we want? The answer to that lies in something about the direction the golden rule sets us in. It makes our tests more resilient by directing us to test the right things. But how? That has everything to do with focusing our tests on user intention.

Testing with Intent or testing implementation details?

When we Test with Intent, our tests are focussed on the way a user intends to use our app. The opposite of that is testing implementation details. We are testing implementation details when any part of our tests touches something that is part of the technical structure of the app.

Kent C. Dodds has a great article about why testing implementation details is bad, In it he defines implementation details as follows:

Implementation details are things which users of your code will not typically use, see, or even know about.

So, we are making a clear distinction between technical things—things that help us build our app—and things that users interact with. When creating an app, we carefully architect its structure and write line upon line upon line of code. All this is implementation details. The purpose of all of this work on implementation details is simply to put something interactive in front of a user.

To use an analogy, think of a light in your room. In this case, our implementation details include most of the light switch, the wiring, the light fixture, and the workings of the bulb. Our interactive elements include the bit of the switch you physically touch, the mechanism to screw in the lightbulb, and whether or not any light is actually being emitted. Those are the only bits that we care about as a user of a lightbulb. Everything else is implementation details.

Let’s look at a simple technical example of what we mean here. Instead of using the above queries in our test case, we could have got the “Dashboards” link using its ID. Something along the lines of:

document.querySelector('#dashboards-link');

But you should ask yourself, does my user interact with my element’s ID? The answer is the same as for the question, am I avoiding testing implementation details? A user simply does not care about an element’s ID; IDs have no consequence for user experience. So, in this case, the answer is no; you’ve not avoided testing implementation details.

So how do we avoid testing implementation details? You can consider yourself safe if your test cases:

- Only touch things that a user would interact with, and

- Only touch those things in a way that a user would.

As a quick aside, part of the beauty of Testing Library is that it gives us the answer to that second point. The whole point of it is that it is a set of tools that help us to code tests that only touch things in a way that a user would.

This is what Testing with Intent is about. It’s about focussing our tests on users. It’s about avoiding implementation details. Now why’s that good?

Test resilience: saying goodbye to implementation details

We’ve already discussed how our tests are failing for the right reasons if something has broken for our users. Well, when testing implementation details, a test failure does not necessarily mean a change to user experience.

| When Testing… | Implementation Details | …a test failure means… | Something changed in our implementation |

| User Intention | Something changed for our users |

There’s some consequences to avoiding testing implementation details. Why’s that?

- If something is an implementation detail, changing it does not impact our users

- If something doesn’t impact our users, it’s for us! We can do what we want with it.

Avoiding getting bogged down in technical implementation detail is fantastic for test resiliency. It is very freeing. Have you ever had the experience of making some technical change that caused havoc in a test suite? A change that didn’t impact user functionality but still broke a load of tests? It’s annoying, but it also shouldn’t happen. The technical details should be there for us, the delivery team, to tweak as necessary.

If you free your tests of implementation details, you free yourself to be able to make sweeping technical changes. You free yourself from having to rewrite tests while refactoring. You are giving yourself the confidence that your sweeping changes haven’t broken anything for your users. So be free. Go wild; re-write your Angular app into React! Why shouldn’t you? (Disclaimer: I take zero responsibility for the outcome of that action!)

Okay, coming back to Earth now. At this point, you may be thinking something along the lines of, “but the example test case above still looks pretty technical”. This brings us back full circle to our golden rule: “Wherever possible, use queryByRole”.

The golden rule revisited

To better understand why we aren’t testing implementation details, we need to unpack what we mean by a role. The role from queryByRole is an element’s ARIA role. Essentially, these roles help to convey some semantic meaning about the purpose of an element. Example roles include link, button and dialog.

Some HTML elements come with a predefined role. An <a>, for example, has the link role. Similarly, you can probably guess the role for a <button> element. There are other roles—such as dialog—that do not have a corresponding HTML tag that uses the role by default. You have to explicitly specify them.

ARIA roles are intended to help tackle issues of accessibility. The roles are meant to be consumed by users in order to help them better understand the context of your webpage. Users with good vision often infer the role from the way an element looks. But still, barring bad UX design, they do understand the role, or purpose of the element. However, not everyone is able to pick up on these visual cues.

We design buttons to have a certain clickable look to them; most users have no need to check their role. But, if you can’t see that clickableness, the role is very important. Similarly, landmark roles support keyboard shortcuts that aid someone with site navigation. They help a user to quickly focus the right part of the page in order to find relevant links.

Now, it’s also best practice to make sure that anything that your users interact with has a role. To be clear, there’s a distinction here between what users passively consume—text for example—and what they actively interact with—headers, inputs, buttons, links,….

With this information, it’s time to revisit our test case. You should now see that it only interacts with things that are intended for our users. There’s no implementation details here. Through Testing Library, we only touch roles and their corresponding text labels:

it('should display the My Dashboards page', async () => {

render(<App />);

const appNavContainer = screen.getByRole('navigation', { name: 'App' });

const dashboardsLink = within(appNavContainer).getByRole('link', { name: 'Dashboards' });

userEvent.click(dashboardsLink);

const dashboardPageHeading = await screen.findByRole('heading', { level: 1, name: 'My Dashboards' });

expect(dashboardPageHeading).toBeInTheDocument();

});

This is one of the powerful consequences of the golden rule. By following it, we are being directed away from implementation details. Instead, we are being directed towards user interaction. In turn, we are being directed towards tests that break for the right reasons—tests that break when something breaks for our users. This means, we are being directed towards being free to make our technical changes.

Beyond better tests: tackling accessibility

Now, improving your test suite is an awesome motivation for adopting this in and of itself. Tests that avoid implementation details and break for the right reason will make your delivery more effective. But, there’s another powerful consequence of following the golden rule; it has a positive impact on accessibility.

On the home page of Testing Library, there’s a claim that it is “Accessible by Default”. This sounds great—and is great—but I couldn’t find any more detail about how this claim works. As I’ve used Testing Library, my understanding of this has grown into what I’m about to describe.

If you follow the golden rule, you will always be looking to use roles in your queries. But which role should you use? The point here isn’t just to pick any old role and hope for the best. As we’ve discussed, the role is directly related to the meaning of an element. You are trying to actualise some intention in your test. You have a reason for interacting with a particular element. There will be a corresponding role for that reason, you just need to look it up. Maybe you are trying to fill in an input; use the correct input role. Maybe you are trying to click a button; use the button role. Maybe you are checking that a confirmation dialog is displayed; use the dialog role. Find the role that corresponds to your motivation and use it.

A quick side note while we are here. It’s best practice, wherever possible, to opt for semantic HTML elements that have a default role. Use a <button> rather than adding a role to a <div role=”button”>. Use a <nav> rather than <div role=”navigation”>.

So how does this help with accessibility? In my first post in the series, I described two barriers teams face in tackling accessibility. The first of these was Accessibility as a Feature. This is the tendency of teams to put accessibility on the backlog and delay—often forever—its implementation. If we are serious about tackling accessibility, we need to address it from the start.

But that’s exactly what we are doing here. By ensuring that we are choosing the right roles for our tests, we are addressing issues of accessibility from the start. If you follow the golden rule, your app will be more accessible by default. It’s no silver bullet that will solve all accessibility issues, but it is a big step forward.

Small, achievable learning opportunities in Accessibility

The second barrier that I described in the first post was a skills gap. Generally, technical teams want to create accessible products, but they don’t have the necessary skills or experience. This makes sense; they don’t have the skills because there’s no opportunity to learn them. We don’t create opportunities to learn if we aren’t building accessible products.

Personally, I find that I learn best when I’m solving real problems as part of my day-to-day work. I must admit that I started practising Testing with Intent with a pretty woeful knowledge of accessibility. I could try and feel better by convincing myself that this was typical of the industry. Really though, it was inadequate for my interests and level of experience.

But through the techniques described in this post, I’ve steadily built my knowledge. In the course of writing tests, small, achievable learning opportunities keep coming up. Each time I take one of these opportunities, I learn something. Consequently, I now code apps that are much more accessible when compared to where I started.

How do these come up? By following the golden rule. When you ask yourself what the correct role is for an element, you are presenting yourself with a learning opportunity. You can go and look it up and learn something along the way.

To highlight this, consider the below scenario:

- I’ve been tasked with implementing a navbar. That’s straightforward, so, in my ignorance, I throw together something along the lines of:

<div class="navbar">

<a href="/">Home</a>

<a href="/dashboards">Dashboards</a>

<a href="/data-entry">Data Entry</a>

<a href="/search">Search</a>

</div>

- I then go to write some tests for this code. I follow the golden rule and opt to use

getByRoleto identify the navbar. But, what role does adivhave? - I look that up and discover that “Non-semantic elements in HTML do not have a role”. Okay, this isn’t the time to abandon the rule. I need to search the page to find the appropriate role for this situation.

- I find the

navigationrole. This looks—and is—perfect, so I read the description. - This, in turn, leads to me reading a bit about landmark roles.

- Using what I learnt, I go back and update my code so that the correct role will be applied:

<nav class="navbar" aria-label="App">

<a href="/">Home</a>

<a href="/dashboards">Dashboards</a>

<a href="/data-entry">Data Entry</a>

<a href="/search">Search</a>

</nav>

- I can then get on with writing my test using the golden rule.

In the course of my work, I spent roughly 10 minutes improving my knowledge. But that small amount of time was really valuable. The topics covered here are actually key accessibility techniques. I’ve learnt useful skills and doing this also has directly improved the quality of my code. It has also made the application more accessible. And, this wasn’t something challenging for me; it was an easy learning opportunity.

So we can break down this second barrier. By following the golden rule, we can make progress by tackling accessibility in steps. While Testing with Intent, small, achievable learning opportunities naturally appear. Each one is a step where we can engage with and learn about accessibility. Oh, and also, writing tests is a lot more fun when you’re learning things along the way…

Encoding intent through accessibility

So, we’ve seen how following the golden rule can help us with both our test suites and accessibility efforts. But there is one final link to make between testing and accessibility.

When we talked about ARIA roles and labels earlier, we talked about how they are used to describe context or meaning for how something works. I like to think of them as our way of encoding how we intend our app to be used. The reason to do something doesn’t have to be inferred—particularly visually—as it’s set out explicitly. That explicitness helps all users to interact with our webpage.

But we can also flip this completely on its head. In Testing with Intent, we are trying to encode user intention into our tests. But how do we do that? That’s not always straightforward. Often the intention of something on a page isn’t easy to get at technically. Often, we encode meaning in ways that are hard to target in code. You’ll struggle to write a selector that manages to capture what we mean by “looking clickable”. Sound familiar? These happen to be the same issues faced by users of assistive technologies.

The answer to how to encode intention? As we’ve discussed, that’s exactly what ARIA roles and labels are for. They encode the intention. This is the golden rule in different words. “Always queryByRole” can be considered the same as “always test with user intention”.

By following the rule, we cause ourselves to expose the intention of each action in our test. Said another way, by targeting the things that convey intention, we represent that intention in code. This is how we encode our user intentions in a test. This is also how, without any textual descriptions, you can read a test and understand what a user is trying to do.

const dashboardsLink = screen.getByRole('link', { name: 'Dashboards' });

userEvent.click(dashboardsLink);

const dashboardPageHeading = await screen.findByRole('heading', { level: 1, name: 'My Dashboards' });

expect(dashboardPageHeading).toBeInTheDocument();

So we use ARIA roles and labels to clearly explain the intention of our application to all users. We use those very same roles and labels to capture and represent user intention within our tests. ARIA is there to assist our tests, as well as users.

In this way we are using one technique to drive better accessibility and drive better tests. Our app is better described so it is more accessible. As it is better described, we are able to code tests through user intention rather than implementation details. And, avoiding implementation details means better tests. In this situation, everyone wins.

Some final thoughts

For me, it’s quite incredible that there can be so much depth behind a simple prioritisation. That, by following the golden rule, you can reap such benefits in your tests and in accessibility. I hope that you’ll give it a go. If you do, please let me know how you get along. I’m always up for refining the ideas here.

This rule goes beyond Testing Library. It can easily be applied to E2E tests for example. But, Testing Library is an awesome tool itself. If you haven’t yet, I really recommend trying it out. If you’re keen, you can jump right in with their getting started guide.

You might also be interested in the other post in this series, and the other view it takes on this topic. Rather than how this fits together technically, the post looks at why this approach is good for testing and accessibility. It’s broader in scope, and talks about why it’s important that we address these issues.

If you’re after more reading, you might want to check out Kent C Dodds—who created Testing Library. He has a fantastic blog. In particular, I found the following posts really insightful:

- The Testing Trophy - which tests should we use most of

- Static vs Unit vs Integration vs E2E Testing for Frontend Apps

- Confidently Shipping Code - why you test

- Testing Implementation Details - why this is bad

Finally, I must also give my massive shout out to Jim Light. We developed these principles and practices while working on a project together. Time got the best of us, and we weren’t able to collaborate on writing these posts together. The original plan was that I would write the other post, and this one would have been his. Safe to say, I may have covered the topic in my own style, but this post has Jim’s stamp all over it.