In November 2009, Google released their previously internal Closure Tools package, consisting of the Closure Library, Compiler and Templates, to the open-source community with the intention of allowing users to create web applications as advanced as their own.

Initially considered a "20% project" for a selection of Google employees, the popularity of the Closure Tools has greatly increased over the last 10 months, with the associated discussion groups attracting a plethora of web developers and JavaScript enthusiasts.

Google's initial release had the intention of seeing what the public could do with their tools. Despite this, it was not until June 2010 and Closure Tools' integration with the "Make Open Easy" toolkit, from the Google Open-Source Office, that community submitted developments really became as important and prevalent as they are now.

The integration with MOE allowed Google to put the patches through their internal version control system with ease, meaning patches (whilst still being closely examined for correct style and design) could find their way into the latest release.

So do the Closure Tools live up to Google's name? How do they work? What are the benefits of them, the drawbacks? These questions and more are asked of the Closure Tools, and in this series of blog articles I intend to document my experience using the Tools.

Putting the Java back in JavaScript?

Alright, so the Java in JavaScript doesn't actually mean anything, but Google have introduced some techniques in their Closure Library to make it more like a classical language such as Java or C#. Take the following example:

// Say what this file provides

goog.provide('com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car');

// Say what this file requires

goog.require('goog.math.Coordinate');

// Constructor of Car object

com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car = function() {

this.miles = 0;

this.gpsLocation = new goog.math.Coordinate();

};

// drive method on the Car object

com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car.prototype.drive = function(milesToDrive) {

this.miles += milesToDrive;

};Naming Conventions

The constructors of objects are always given capital letters and methods begin with a lower case letter, and then styled using camel casing; typical Java naming conventions.

Namespacing

Although not a new idea, the Closure Library uses a concept of namespaces in its JavaScript. This creates an object hierarchy on the global object similar to dot notation in Java packages. It is then assumed that each JavaScript module will be under its own namespace, reducing the chance of global conflicts (we can never be sure that there isn't another JavaScript module using com.scottlogic!)

So what do goog.provide and goog.require actually do?

Namespace Initialization

The provide statement will, for one, ensure that the correct Object is initialized on the global scope. In the above example, this means that making sure there exists an object com on the global object, with a property named scottlogic of type Object, with a property named vehicle of type Object.

Thus, when you define com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car, the function Car will be assigned to the correct object without error.

Assuming no other page in the world uses the com.scottlogic namespace, we are safe to use this and not pollute any pages.

The Library's naming convention favours lower case file names, and the file location mirrors Java's convention, so the file car.js would be found at com/scottlogic/vehicle/.

Dependency Management

The provide statement also plays a part in dependency resolution. When a script runs, the Library has to analyse the dependencies on each file, to ensure the correct files are pulled in. If you're using the Library without the compiler, this is done in the web page, using base.js (part of the Closure Library). Take the following HTML:

<html>

<head>

<script src="closure-library/base.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

<script>

goog.require('goog.date.UtcDateTime');

</script>

</head>

<body onLoad="alert(new goog.date.UtcDateTime().toString());">

</body>

</html>goog.require is a function defined in base.js, so there is a guarantee it exists. The require statement then adds a new script tag to the HTML, pulling in the dependency (goog.date.UtcDateTime). The process then repeats for each dependency of the root, forming what is known as the dependency tree.

Things work a little differently if you're compiling your code with the Closure Compiler. Because there is no concept of a web page, the dependency tree of each input file is analysed before anything happens. The logic for calculating the dependencies is located in the Compiler script.

Once the full dependency tree has been calculated, the Compiler is "fed" the files, in order, as input. The compiled JavaScript file is then guaranteed to have all the necessary files, and in the correct order.

Dependencies for your own namespaces

For this method to work without the Compiler, the Library needs to know the following about every file:

- Where the file is

- What the file provides

- What the file requires

This is all stored in the deps.js file, located in the same directory as base.js. Imagine the require statement in the above HTML as the root of the tree. base.js looks up the namespace that is being required, and pulls in those dependencies as explained. All this is done using the Closure Library file deps.js.

But what if you require a namespace you have provided? Consider the following HTML, using the Car example above:

<html>

<head>

<script src="closure-library/base.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

<script>

goog.require('com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car');

</script>

</head>

<body onLoad="alert(new com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car());">

</body>

</html>The Library has no idea where to find the file that provides com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car, nor where to find its dependencies, because this particular dependency branch is not defined in deps.js. The solution to this problem is the generate your own dependency file, using the Closure-supplied depswriter.py.

Depswriter works similar to the Compiler in terms of its arguments and execution process. Take the following command:

python closure-library/depswriter.py /

--root_with_prefix="com/scottlogic/vehicle com/scottlogic/vehicle" /

--output_file="closure-library/myDeps.js"root_with_prefix defines, unsurprisingly, the root and the prefix to the file from base.js. So if you have depswriter.py and base.js in the same directory, the root and the prefix will be the same.

This will output a file named myDeps.js in the closure-library directory, which will look something like this:

goog.addDependency('com/scottlogic/vehicle/Car.js', // location of the file from base.js

['com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car'], // what the file provides

['goog.math.Coordinate']); // what the file requiresNow the Library knows where to find com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car, and what it requires. You would then add this new dependency file to your HTML as such:

<html>

<head>

<script src="closure-library/base.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

<script src="closure-library/myDeps.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

<script>

goog.require('com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car');

</script>

</head>

<body onLoad="alert(new com.scottlogic.vehicle.Car());">

</body>

</html>A JavaScript file can provide and require multiple Objects, but Google's convention is to keep individual objects to their own file.

Creating a library from the Library

Although there are many examples of the Closure Library being used in web applications, there aren't many publications of the Library being used to create another library, to then be used in web applications.

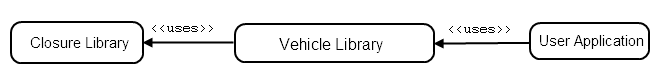

For example, if we were to create a library that gives the user application access to a large range of vehicles, a high level view of the project structure may look like this:

Size issues with including the entire Library

As you'd imagine, the extensiveness and sheer size of the Closure Library meant integrating the entire API into another library doesn't make much sense, and would result in a huge JavaScript file being sent across the wire. This is where the Closure Compiler comes in.

As explained in the Compiler documentation, one of the benefits of using the ADVANCED_OPTIMIZATIONS tag when compiling is the removal of all unused functions and dead code. Take the following code, extended from the above example:

ClosureLibrary = function(){

alert('This is the Closure Library');

};

ClosureLibrary.prototype.unusedFunction = function(){

alert('This is an unused function.');

};

ClosureLibrary.prototype.usedFunction = function(){

alert('This is a used function.');

};

VehicleLibrary = function(){

alert('This is the Vehicle Library');

var closureLibrary = new ClosureLibrary();

closureLibrary.usedFunction();

};So here we have the Closure Library and the vehicle library represented as JavaScript objects. The Closure Library has 2 functions, but only one is used by the vehicle library. Obviously on a larger scale, this would cause a lot of dead code. However, when we run the code through the compiler service, we get the following output (I've added whitespace for clarity):

ClosureLibrary = function() {

alert("This is the Closure Library")

};

VehicleLibrary = function() {

alert("This is the Vehicle Library");

new ClosureLibrary;

alert("This is a used function.")

};We can observe that 2 things have happened here:

- The compiler has completely removed the unusedFunction from the output. Running the entire library through the compiler would result in huge savings of space from dead code removal.

- The compiler has inlined the usedFunction. This is an added optimization offered by the compiler which replaces a function call with the function body. Although this doesn't necessarily document my point of dead code removal, it is a very useful optimization that saves quite a lot of space.

Of course, this only demonstrates one benefit of using the Library and the Compiler together.

Support From Google

Each Closure Tool has its own group, hosted at Google Groups. The involvement of the Google staff within the group is excellent; every day key contributors to the project post answers to user questions and queries.

This close relationship between the developers and the community has definitely been one of the strengths of the project. Not only are specific problems solved, but the backlog of questions and answers provides almost another API to the Tools.

The team also maintain a Closure Tools blog, which is updated with important information about the tools and subsequent releases.

The Fourth Tool - Closure Linter

Very recently, a fourth tool was added to the Closure Tools: Closure Linter.

Although this is very new, it would appear to be a JSLint implementation that uses Google's JavaScript style. It provides 2 scripts: One to check code, and one to attempt to correct code.

This seems to be a fitting addition to the tools, as Google seem to open-source more of their internal toolkits. However, the quote in the API,

"You must use

--strictif you are contributing code to the Closure Library."

could imply that this release prepares the Closure team to accept even more patches to the rest of the Tools.

Conclusion

The Closure Library is a very powerful and capable JavaScript library that allows the user full access to some of the most advanced JavaScript UI widgets and programming functionality currently available. However, its size is quite a large setback, being one of the largest JavaScript libraries.

Of all the Tools I have used, the Closure Compiler is probably the easiest to "pick up and use" in any web project, given that it can optimize code without any bearing on the source or the functionality, whilst providing significant gains.

However, the real power of the Closure Tools comes when you combine the two (or more, thanks to the recent introduction of Closure Linter), resulting in access to the Library whilst reducing it's size by a considerable amount.

The Closure team are very responsive to any issues brought up on the mailing list, meaning getting help is easy. They are also responsive to issues brought up on their tracker, meaning that minor problems are usually solved within a commit or 2.

Building web applications is becoming an increasingly hot topic, and the performance, size and cross-browser benefits of the Closure Library make it a key player in this advancing technology.