The Web Workers API is currently a draft HTML5 specification which defines an API for running JavaScript in a background thread. In this series of blog posts I am going to investigate the practical use of Web Workers.

In this first blog post I want to look at the performance of HTML 5 Web Workers in different browsers. I don't just mean the performance increase that we're going to see by multi-threading our JavaScript, I also mean the difference in performance between executing the same code in a Worker vs. the UI thread, and the set-up cost of creating workers and the associated messaging involved.

Introduction to Web Workers

Web Workers are created by writing a block of code in a separate js file. This piece of code is then executed in an entirely separate context - it has no access to the window object, it can't see the DOM, and it receives input and sends output via messaging. The messages are serialized, so the input and output is always copied - meaning we can't pass any object references into workers. Although initially this seems like a serious downside, it can also be viewed as a great bonus - it forces thread safety.

To implement a worker, we have to create worker code in a new file. It needs to confirm to a specific "interface":

onmessage

implement this function to receive messages from UI thread

onconnect

implement this function in a Shared Worker, to receive notification when multiple UI threads (ie. from multiple windows) connect to the same worker instance

postMessage

call this function to send a message back to the UI thread

Since a Worker doesn't have access to the window object, you can't use all the window functions you are used to (self is the global object in a Web Worker). However you can still use these:

setTimeout

setInterval

XMLHttpRequest

Here is a simple implementation of a prime-number calculating Worker, primes.js:

self.onmessage = function(event) {

for(var n = event.data.from; n < = event.data.to; n += 1){

var found = false;

for (var i = 2; i <= Math.sqrt(n); i += 1) {

if (n % i == 0) {

found = true;

break;

}

}

if(!found) {

// found a prime!

postMessage(n);

}

}

}Here we have implemented a function called onmessage, and that function calls postMessage with its results. To make use of this Worker, we have the following piece of code in our page:

var worker = new Worker('primes.js'); //Construct worker

worker.onmessage = function (event) { //Listen for thread messages

console.log(event.data); //Log to the Chrome console

};

worker.postMessage({from:1, to:100}); //Start the worker with argsThis constructs a new Worker object using our worker definition file. Each time it receives a message from the Worker, it is output to the console.

But this post isn't supposed to be a Worker tutorial: on to the performance measurements.

Worker thread vs. UI thread

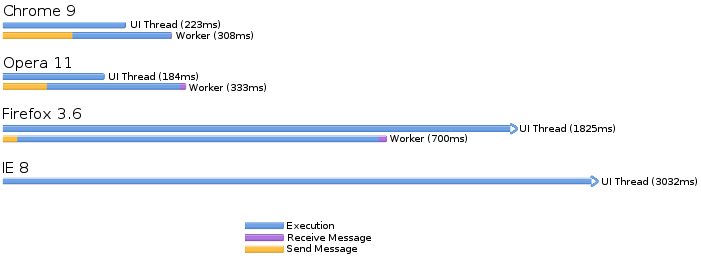

To run the following tests, I updated the worker above by adding timestamp measurements at the start and end of the onmessage function. They are then passed out through the result object at the end. This allowed me to get the exact time when the function started and finished execution, enabling measurement of the time taken to send a message to the worker, the time for it to execute, and the time for it to send a message back to the UI thread.

var time = new Date().getTime();I also ran the same algorithm without the use of any workers. The parameters in both cases were from 1 to 100000. Everything was repeated in Chrome, Firefox, Opera and IE.

In Chrome, the Worker execution time is a little longer than the UI thread, and the setup time is bigger than the other browsers. Since this is a constant, it will become less significant as the Worker does more work, or is reused.

In Opera, execution also takes a little longer in the worker, but again the setup time is a bigger factor as with Chrome.

In Firefox, the Worker is more than twice as fast! I don't know why this is. My only guess is that the UI thread is busy doing other things. The setup time is minimal. Firefox seems to like workers, but in saying that, it's still slower than Chrome and Opera.

In IE...well, it doesn't implement workers, and the UI thread takes a long time. Maybe with IE9 we'll see better JavaScript performance but we won't see Web Workers.

Multiple Workers vs. Single Worker

In all of the tests above, core 1 of my dual-core CPU shot to 100% usage while core 2 remained idle. That's a bit of a waste, and that's where the benefits of Web Workers should be seen.

So let's repeat the tests above, using two workers instead of one. IE is left out this time for obvious reasons. All timing is in milliseconds.

| Browser | Construction | Avg. message sending |

Avg. execution |

Avg. message receiving |

Total time (load to completion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrome 9 | 1 | 175 | 92 | 7 | 290 |

| Firefox 3.6 | 1 | 32 | 525 | 5 | 614 |

| Opera 11 | 200 | 50 | 99 | 50 | 202 |

Consistently we see that two workers are only slightly faster than one, but that is entirely due to the overhead involved in creating each worker - the actual execution time doubled in speed.

But there is definitely something strange going on with Opera! The time taken to construct the workers is almost equal to the total time required. This means the UI thread is busy whilst the workers are running, and the UI thread won't get to see any benefits as is the case with Chrome and Firefox. If Opera was more popular I'd spend time investigating this quirk, but it's not, so I won't!

Sending/Receiving Large Messages

Workers communicate with the UI thread via messaging, and those messages are copied. If we pass an object to a Worker, it's serialised to JSON, and this serialisation and copying process is going to require effort. Let's measure exactly how much effort. I've removed the work from the Worker and I simply pass it an object, and it pings that object back. We take a timestamp within the Worker so we know exactly when it's run. This is the Worker code:

self.onmessage = function (event) {

postMessage({input:event.data, received: new Date().getTime() });

};And this is how we consume it:

var worker = new Worker('ping_worker.js'),

startT = new Date().getTime();

worker.onmessage = function(event){

console.log("Time to send message to worker: "+ (event.data.received - startT));

console.log("Time to receive message from worker: "+ (new Date().getTime() - event.data.received));

};

worker.postMessage({/* test object */});For each browser, I ran the above code both with and without a large (100KB) object in the postMessage argument. This let me find the time delta which indicates the time lag induced by passing the object. Again all times are in milliseconds.

| Browser | Send empty | Receive empty | Send large | Receive large | Send large delta |

Receive large delta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrome 9 | 112 | 9 | 135 | 34 | 23 | 25 |

| Firefox 3.6 | 27 | 3 | 34 | 38 | 7 | 4 |

| Opera 11 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

I think we can safely conclude that serialisation/deserialisation and message passing doesn't take a significant amount of time, especially compared to the overhead of constructing the worker.

Conclusions

Performance

Sometimes workers take longer to execute than they would in the UI thread, sometimes they're faster. However, doing work in a Worker means the UI thread is free to concentrate on a responsive UI. Of course, any potential benefits are totally lost if the Worker is only doing a little work, because it's not worth the overhead required to construct the Worker.

Limitations

Because of the context that a Worker is run in, it has no access to the window object - or any other global variable. Additionally, object references can't be passed into the Worker. This means that there will probably only be specific situations in which a Worker can be used, ie. Long-running algorithms. In my experience the most time consuming operations usually involve DOM interaction and that isn't possible in a worker.It doesn't look like IE9 is going to support workers, so whatever happens, we can't speed up the slowest browser! Additionally, we have to code alternatives for browsers that don't support workers so that the JavaScript doesn't break.