Reading Avi Itzkovitch's article about Creating An Adaptive System To Enhance UX on Smashing Magazine recently brought the notion of adaptive design back to the forefront of my mind again. For those unfamiliar with the concept, from Avi's article:

In computer science, the term "adaptive system" refers to a process in which an interactive system adapts its behavior to individual users based on information acquired about its user(s), the context of use and its environment.

That same evening, browsing around reading various articles about adaptive design, it struck me why when it comes to the practicalities of adaptive design I go a bit cold: the frustration adaptive design causes when it goes wrong often outweighs the delight it creates when it works. What prompted this was not the articles I was reading but the behaviour of the smartphone I was using to access them on. The automatic re-orientation of the screen from landscape to portrait and vice versa based on the device's perception of its orientation is a common example of a generally useful adaptive system.

Assumptions are the termites of relationships - Henry Wrinkler

However, in the context of lying on your side in bed, as I was, you soon realise the flawed assumption this system operates on. The orientation of the screen is based on the orientation of the device relative to the ground, and therefore is essentially assuming you are upright. This means that any context where you are not upright when looking at the device (or the device itself is not upright, for example lying on a desk) becomes an awkward battle. The result is usually that you change your or the phone's position to accommodate this behaviour, i.e. you adapt to suit the device, the polar opposite of the goal of adaptive design. What the device "should" be doing is to orient the screen based on its orientation relative to the user.

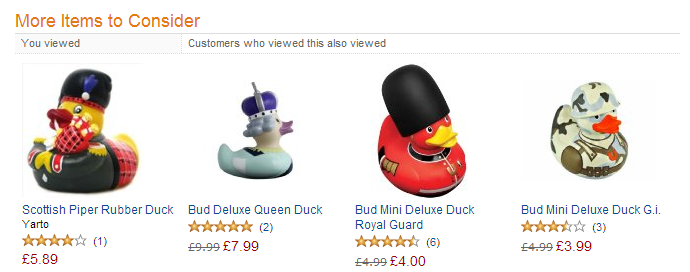

A different kind of of common adaptive system, recommendation services, suffer from some equally strong and arguably misplaced assumption: that a only a single individual will be accessing the service through any particular browser/machine/device. Amazon, for example, recommends other items that may be of interest based on your browsing and purchasing history. At home, my wife and I share a desktop and laptop, and because we are both "lazy" we do not bother with separate user accounts because that would result in half our time spent logging in and out. What this means when it comes to Amazon is that we often get a good idea of what the other one was recently looking at because it doesn't require explicit log-in before it starts tracking the user. As a result, when I saw the More Items To Consider list yesterday it became pretty clear that I, or someone else in our family, is going to be getting a themed rubber duck for Christmas...

Similar frustration results from other services operating on the same, in my opinion, flawed assumption. For example, it is quite grating to suddenly be hit by a blast of horrendous easy listening music from Last.FM just because my wife used the same device as I did to listen to her music.

Although these kinds of frustration are caused by us not using the services as expected, it can be quite hard to rectify. In the cases of both Amazon and Last.FM there are fairly obtuse mechanisms for editing what they have tracked, but should the user have to fix the adaptive system or is this a symptom that the adaptive system is flawed?

Mindless habitual behaviour is the enemy of innovation - Rosabeth Moss Kanter

The Amazon and Last.FM recommendation services fall into a broader category of adaptive systems that attempt to use past behaviour to predict future behaviour. Google use this approach in all sorts of ways, from their searching functionality to the advertising that is presented in some places and beyond. In fact, they are taking this even further to assist us in many aspects of our everyday lives with Google Now:

I believe it is worth considering these kinds of systems in a bigger context, on a more philosophical level. Given that they are based on past behaviour they are (currently) unable to encourage any real change. In fact, they are inherently based on the notion that you as a user don't drastically change. While in some respects this is true, as we become more dependent on these kinds of systems it becomes something of a self-fulfilling prophecy because it takes increasingly more conscious effort on our behalf to essentially override or ignore what the system is doing for you. Furthermore, if we do significantly change our behaviour then the system loses its efficacy for a while, thereby frustrating us and, if our dependency on them becomes sufficiently strong, actually discouraging any other change.

This only scratches the surface of one consequence of the increased prevalence of adaptive systems. However, regardless of where you stand on their consequences, it is important that we do recognise and consider them, especially those involved with creating them, rather than passively allow them to change us.

If there is no struggle, there is no progress - Frederick Douglass

Adaptive systems can greatly enhance the experience of many products, but conversely can also undermine it. By their nature they attempt to infer contexts of use, which are hugely variable and complex, especially when human factors are involved. Therefore they require significantly more comprehensive and well thought out user testing. At the same time, designers and developers should thoroughly examine the system and any assumptions it operates on for flaws, and then consider whether the overall experience of the product can overcome any issues that might arise for users. Furthermore, readily accessible mechanisms should be provided to allow any adaptive system behaviour to be overridden by the user if they so desire.

As device sensors and our understanding of human behaviour improve, adaptive systems are going to become evermore prevalent and hopefully make experiences increasingly productive and intuitive. However, on a more philosophical level, this means we should more readily question them and recognise that adaptive systems are just as capable of creating and altering behaviour (for good or bad) as they are at enhancing existing behaviour.