In my last post Single Page Applications - Angular vs Knockout, I built a Single Page Application (SPA) using Angular and Knockout (with CrossroadsJS and RequireJS). Both solutions unit tested the model code, but I glossed over the idea of end-to-end (e2e) testing, so I’d like to take a closer look at that now.

I’ll start by looking at how we can implement e2e tests in both solutions. Next, I’ll consider the value of having these tests, how brittle they can be, and therefore the cost of writing and maintaining them. Finally, I’ll suggest a couple of ways to reduce the cost by making the tests more robust.

As before, I’ve put the finished project on GitHub: e2e-Angular-Knockout. To make the tests more realistic, I’ve replaced the mocked server I used previously with a real web service (implemented in Node). Having a real server means no live demo this time, but it still looks just like the previous version (Knockout demo and Angular demo).

Test frameworks

Test Angular using Protractor

I used angular-seed to build my Angular solution, and that comes with a sample e2e test that uses a tool called Protactor. The Angular and Knockout websites look identical, so I suggested that the same e2e tests should work in both versions. However, that isn’t entirely true.

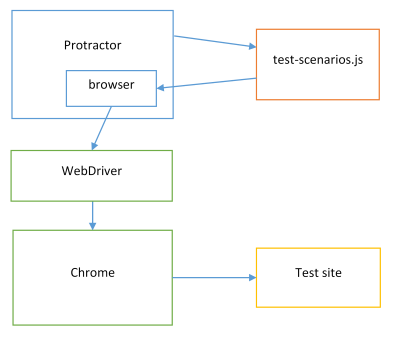

Protractor is an end-to-end test framework built specifically for Angular. It looks for the Angular object in the running web site and interacts with it in various ways. For example, it will automatically wait for $http asynchronous requests to finish, which makes coding e2e tests a lot simpler. Unfortunately it also means that tests written with Protractor won’t work with my Knockout solution.

Protractor is a Node.js program built on top of WebDriverJS (which drives a real browser like Chrome). Install Protractor using npm:

npm install -g protractor

Once installed we can use the webdriver-manager tool to download the necessary binaries for WebDriver and start a server:

webdriver-manager update

webdriver-manager start

Then run the tests:

protractor test/protractor-conf.js

Protractor runs the Jasmine tests, making a browser object available so that the test can navigate to and control the website under test:

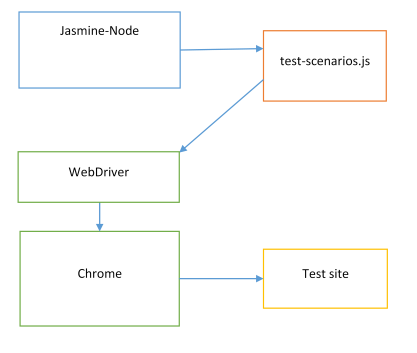

Test Knockout using Jasmine-Node and WebDriverJS

The Knockout solution can’t use Protractor, but we can still run Jasmine tests from Node using jasmine-node, and control the website directly using selenium-webdriver.

npm install jasmine-node -g

Download and install a copy of ChromeDriver, then add the folder to your PATH:

SET PATH=%PATH%;C:\Users\...\npm\node_modules\chromedriver\lib\chromedriver

Then run the tests:

jasmine-node test/e2e/ --captureExceptions

Writing tests

Each test will navigate to a particular page in the application, optionally apply some action to that page, then test the resulting DOM to make sure everything is as expected.

Controlling a browser and waiting for results is inherently asynchronous. As well as the initial page load, each of the components on the home page immediately make their own Ajax requests, so we also need to wait for those to finish before we can start the next step of the test.

Protractor makes this easy. It knows the website is implemented with Angular, so it can wait for Angular’s initialisation process to complete, and for any $http calls to finish. The asynchronous behaviour is hidden away so it’s simple to test, for example, that the Investments table has twenty rows:

it('should list all investments', function () {

browser.get('/#/home');

var rows = getRows();

expect(rows.count()).toEqual(20);

});The browser.get() line won’t return until the page has loaded and all $http requests have finished.

In the Knockout tests, we need to write an asynchronous test to control the browser:

it('should list all investments', function (done) {

// Create a webdriver instance

var driver = new webdriver.Builder().

withCapabilities(webdriver.Capabilities.chrome()).

build();

// Navigate to page

driver.get('http://127.0.0.1:8089');

// Wait until the ajax requests finish (we should have table rows)

driver.wait(function () {

return driver.isElementPresent(

webdriver.By.css('investments-component tbody tr'));

}, 1000);

// Find the table rows

driver.findElements(

webdriver.By.css('investments-component tbody tr'))

.then(function(rows) {

// Check the number of rows

expect(rows.length).toEqual(20);

})

.then(done);

});Yikes! Let’s take a closer look at that. First, we create an instance of WebDriver (which opens up Chrome), then we ask it to navigate to our test page. Next, the driver.wait() call waits for a condition to become true, up to a maximum 1000 milliseconds. We want to wait until the table has been populated, so we’re looking for row elements in the table body. Finally, we can get the table rows and test that we have the right number of them.

Even the last bit, where we’re just checking the DOM, is an asynchronous call. WebDriver goes off to find the matching elements and calls back with the result. WebDriver uses promises to make all these asynchronous calls a bit easier to handle, and it has an internal queue of promises so you can simplify the client code a little. For example, driver.wait() is asynchronous and returns a promise, but so does the next line (driver.findElements()), so WebDriver puts it in the queue to be executed after the first one finishes. The final line (.then(done);) tells Jasmine that the test has finished, and we need to make sure that doesn’t happen until after the last promise in the queue.

The first two parts of the test above are going to be needed for every test, so lets pull that out into a new Node module and generalise it a bit:

var webdriver = require('selenium-webdriver');

function DriverController() {

// Create and initialise the web driver

var driver = new webdriver.Builder().

withCapabilities(webdriver.Capabilities.chrome()).

build();

this.get = function (path, selector) {

// navigate to the requested path

driver.get('http://127.0.0.1:8089' + '/' + path);

if (selector) {

// wait for the specified element to be loaded

driver.wait(function () {

return driver.isElementPresent(webdriver.By.css(selector));

}, 1000);

}

return driver;

};

// Make the selector available

this.by = webdriver.By;

};

// Export an instance of the driver controller

module.exports = new DriverController();Here, we’re creating the driver and offering a get() function to navigate to a path, wait for a particular element to appear, and return the driver instance. This approach means we share one instance of the WebDriver between all the tests, which is much faster, but we also need a way of stopping it at the end. To do that I’ve used a custom jasmine Reporter that tells the WebDriver to quit when the test run completes:

// The Reporter class allows us to stop the server after all jasmine tests

function DriverControllerReporter(driver) {

this.driver = driver;

}

DriverControllerReporter.prototype = new jasmine.Reporter();

DriverControllerReporter.prototype.reportRunnerResults = function () {

this.driver.quit();

};

// Hook Jasmine events so we can stop the server at the end

jasmine.getEnv().addReporter(new DriverControllerReporter(driver));Now we can re-write that test for the Knockout version:

it('should list all investments', function (done) {

var driver = driverController.get('','investments-component tbody tr');

driver.findElements(by.css('investments-component tbody tr'))

.then(function (rows) {

expect(rows.length).toEqual(20);

})

.then(done);

});That’s not quite as easy as the Angular version, but we’re much closer. As it happens, this version of the test would actually work on both the Angular and Knockout websites.

Let’s try a more complicated test. This time, we want to type something in the filter query text box, let it query the server and check that we display the correct number of results.

In the Angular version:

it('should list subset of investments when filtering', function () {

browser.get('/#/home');

// Type something in the filter box

element(by.css("investment-filter input")).sendKeys("te");

var rows = getRows();

expect(rows.count()).toEqual(3);

});Thanks to Protractor, we don’t have to do anything special after entering the filter query, since it automatically waits for the $http requests again. Here’s the same test in the Knockout version:

it('should list subset of investments when filtering', function (done) {

var driver = driverController.get('','investments-component tbody tr');

// Type something in the filter box

driver.findElement(by.css("investment-filter input")).sendKeys("te");

// Wait until there are only 3 rows (just a way to check

// that the ajax request has completed)

driver.wait(function () {

return getRows(driver).then(function (rows) {

return rows.length == 3;

});

}, 5000);

getRows(driver)

.then(function (rows) {

expect(rows.length).toEqual(3);

})

.then(done);

});

// Helper function for getting rows

var getRows = function (driver) { return driver.findElements(

by.css('investments-component .panel-body tbody tr'));

};I’ve chosen to wait for the Ajax request to complete by checking for three rows, but this is not particularly elegant (and also makes the subsequent test for three rows redundant). I think if I was implementing this in production, I’d want some sort of ajax-status object in the application, so that the test can more directly wait for outstanding Ajax requests.

Is it worth the effort?

I’ve written a set of e2e tests in both projects. For each page, the test verifies that the page loads and shows the correct heading. For each component, tests verify that the component makes the Ajax request for data and presents the data on screen. They also test that the component updates itself correctly when the filter changes. The tests for the Investments table verify that the correct formatting is used for dates and currencies, and that clicking on a row navigates to the details page.

This is very valuable stuff. If we’re delivering a build after every two-week sprint, and the application is getting bigger and bigger, it becomes effectively impossible to manually test all that behaviour for every build. The e2e tests should be executed by the Continuous Integration environment, so will let us know as soon as we check in code that breaks something.

However, we can’t verify that the web page actually looks right. We can check the content, but the visual appearance depends on css styles and browsers and still needs a human to look at it.

What about the cost? The behaviour of most websites will depend on the data returned by the web service, so trying to run e2e tests against a production or development version of the database is unlikely to be reliable enough - the data will be constantly changing. A common approach is to have a designated test database with a known set of data for running the e2e tests against. Even this approach is likely to be very brittle as the application grows in scale.

For example, imagine I have written a test that enters a filter query and verifies that I get three specific results back that match the filter. Weeks or months later, I may be working on a new feature that needs new investment records in the database to test it effectively. However, the new data means that my earlier test now returns too many results. It’s been a while, so I may have a tough time trying to figure out how to get that old test working again. Even worse, it could be a different team member working on the feature. With a large application, this sort of thing will happen a lot, and you may find that adding one new piece of test data causes several old tests to fail. Tests that are brittle in this way are difficult and expensive to build and maintain, which will discourage developers from writing them.

So what can we do?

Making e2e tests more robust

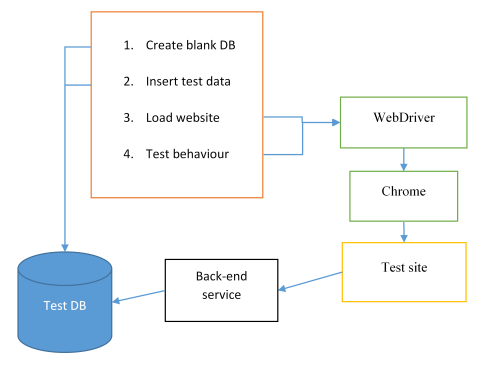

Make tests responsible for their own data

A good way to solve the problem of conflicting data in the test database is to make each test responsible for the data it needs.

We’ll still have a test database, but at the start of each test (or small group of tests), the database is empty (created from the schema, or copied from a template, or emptied from the previous test). The test itself will have a direct connection to the test database, and will insert the data it needs before loading up the website and running the test.

I’ve often used this approach for integration testing of repository code, and it works very well indeed. The tests are robust because they are no longer dependent on each other’s data. Copying an empty database (with just schema) is pretty quick, so the performance is still good.

As the application gets bigger, it may be that a lot more data is required just to get a basic test to run. You may find that instead of starting with a completely empty database each time, it’s better to have some basic seed data. Any data that’s widely used but pretty static is a good candidate. You might also want to have at least one of each type of user too, so it’s easier to have a simple log-in step in tests.

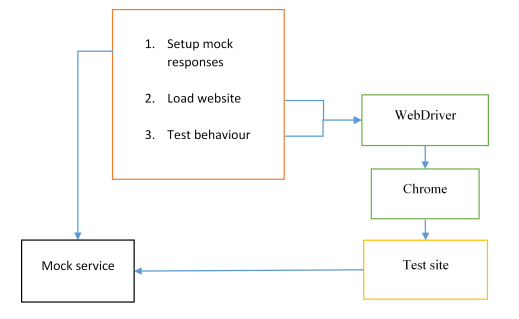

Mock out the back-end server

An alternative to seeding the database is to remove the back-end server completely, and instead provide mocked responses to Ajax requests. If we mock out the server, then it isn’t really an end-to-end test any more (more like a middle-to-end test). However, it may still make sense if you’re developing an SPA and you’re interested in testing the behaviour of the website itself based on predictable responses from back-end services. Another benefit is that you don’t need to get the real server running (with its test database) before running the tests.

Implementing a (very simple) mocked server is easy with a Node module:

var http = require('http'),

url = require("url");

// Create a server that responds with pre-set json fragments

function MockServer() {

var testResponses = [];

// Insert a mocked response

this.get = function get(path, obj) {

testResponses.push({ path: path, response: obj });

};

// Clear the mocked responses

this.clear = function clear() {

testResponses = [];

};

var server = http.createServer(function (request, response) {

var urlParts = url.parse(request.url);

var requestPath = urlParts.pathname + urlParts.search;

// Lookup the mocked response

var result = [];

for (var n = 0; n < testResponses.length ; n++) {

if (testResponses[n].path === requestPath) {

result = testResponses[n].response;

}

}

// Set the headers and return the result

response.setHeader('Access-Control-Allow-Origin',

request.headers.origin);

response.setHeader('Content-Type', 'application/json');

response.end(JSON.stringify(result));

}).listen(54361);

};

module.exports = new MockServer();The mocked server has a get function that creates a mocked response (the JSON object to return for a request to a specific URL). I called it get for HttpGet - a more complete version would have a post method and some way to verify posted arguments. The clear function clears the mocks at the start of each test. As with my DriverController module, we also need a custom Jasmine Reporter to close down the server at the end of the tests (not shown here for brevity, but implemented in the GitHub project).

Now I can setup a mocked response like this:

// Return full investment list for '/analysis'

mockServer.get("/analysis", [

{ name: "Investment-1" },

{ name: "Investment-2" },

{ name: "Investment-3" }

]);

// Return filtered investment objects for '/analysis' with filter query

mockServer.get("/analysis?name=test", [

{ name: "Investment-2" },

{ name: "Investment-3" }

]);Easier to run e2e tests

So far, all my tests still require that the website itself is already running before I start testing. However, I created a Node module that starts and stops a mocked back-end web service, so why not do the same for the web server?

The SPA is just a set of static files (html, css, javascript), so we just need a static web server to listen to a port and serve those files. I’ve used connect and serve-static.

var http = require('http'),

connect = require('connect'),

serveStatic = require('serve-static');

// Create a web server to serve the static pages of the test target

function ServerController() {

var app = connect().use(serveStatic('src',

{ 'index': ['index.html'] }));

http.createServer(app).listen(8089);

};

module.exports = new ServerController();As before, we also need a custom Jasmine Reporter to close down the server at the end of the tests (not shown).

With this in place, we now have a set of robust e2e tests (ok, middle-to-end tests!), which will automatically start and stop the necessary servers for us.

Summing up

I’ve shown how to implement e2e tests for an SPA created with either Angular or Knockout. The Angular version has a clear advantage thanks to the Angular-specific test tool Protractor, which makes tests easier to write. However, it’s possible to do the same things in the Knockout version and it’s not really that much harder.

I promised to talk about the ‘value’ of e2e tests, and the ‘cost’ of creating and maintaining them, due to their often brittle nature. Of course, this boils down to the question of whether you should be writing e2e tests for your application. I won’t presume to answer that for you, but I’ve tried to show how they can be made as robust as unit tests, and nearly as easy to write. Hopefully when you next ask yourself that question, you’ll be more inclined to answer “yes”.