This blog post explores attacks against some pre-made sample web apps running on your own machine. The focus of this post is on securing web apps, rather than the attacks themselves. It is part of an ongoing series of blog posts on web application security, which includes:

Securing Web Applications, Part 1. Man In The Middle Attacks

Securing Web Applications, Part 2. SQL (and other) Injection Attacks

Securing Web Applications, Part 3. Cross-site Scripting Attacks

An important note before starting:

This blog post shows how to perform an attack on a sandboxed sample website. Attacking targets without prior mutual consent is illegal. It is the reader’s responsibility to obey all applicable laws. The writers of this blog post and Scott Logic assume no liability and are not responsible for any misuse or damage caused from the use of this tutorial.

What are these attacks?

In this module we return to the theme of users having their sessions or accounts hijacked - taken over by an attacker. We saw this in previous modules in the context of insecure transport of credentials and session IDs, and in exfiltration of credentials by injection attacks. However, there are many other ways of taking over a user’s account, based on attacking account management features such as registration and login, and we will now take a look at those.

Closely related to this is the detail of how sessions are handled in your application - how the concepts of identity/authentication and authorization persist during the course of a user’s session with a site, and how that increases or decreases their vulnerability to session and/or account hijacks.

Much of this is about the design of features, and the trade-off between security and usability, rather than implementation detail. Unlike the earlier articles on injection and cross-site scripting attacks, there is no single ‘right answer’ to many of these issues.

Real-world examples

Snapchat. Snapchat has had it’s fair share of security-related criticism, perhaps unsurprisingly given that one of their USPs was the additional privacy afforded by the automatic deletion of messages. Amongst the issues they caused themselves was a lack of verification in the registration process, that allowed attackers to create fictitious accounts with other people’s phone numbers. This is now fixed, but the company was the subject of a government law suit about its security and privacy issues. http://resources.infosecinstitute.com/top-5-snapchat-security-vulnerabilities-how-the-app-learned-its-lessons/

iCloud. Apple’s defence against brute force password guessing wasn’t strong enough to prevent a hack of naked celebrity photos. The arms race continues. http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/01/07/idict_icloud_hacking_tool_blunted/

Sarah Palin. Quite old now, but still a classic story of how not to choose security questions, especially when you’re a political figure whose every move is scrutinised. http://www.wired.com/2008/09/palin-e-mail-ha/

GitHub. An automated brute force password guessing from a botnet, which got past their detection systems. A creditable response here https://github.com/blog/1698-weak-passwords-brute-forced

Mat Honan. A frightening tale of a hack facilitated by weak human-operated processes. http://www.wired.com/2012/08/apple-amazon-mat-honan-hacking/all/

Getting Started

This blog post is intended to be a hands-on discussion - at various points I’ll ask you to do things to the sample applications. Obviously you don’t have to - I’m not your boss - but I certainly found doing it a better way to learn than reading about it. This is a bit of a truism, but security is something of a special case, as it you need to get into the mind-set of actually trying to subvert and break your own handiwork. In this particular part of the series, owing to the context-specific nature of the issues, the tasks are rather more loosely defined, and you should feel free to vary them to better suit your own applications, or just use the samples as a sandbox for prototyping.

- Clone the Sandboxed Containers Repo and check out the SQL_Injection branch

- Create the sample apps (and new databases) by running

vagrant upfrom the sub-folders of the ‘samples’ folder. There are two apps, the MEAN stack accessible at10.10.10.10, and Jade, Express & MySQL at10.10.10.20. These apps have basic user login and post making facilities, inspired by Write Modern Web Apps with the MEAN Stack by Jeff Dickey. There’s a third site, an ‘attacker site’ which collects data from the other two apps at10.10.10.30.

Moving on from a previous article

If you’re moving on from a different article in this series you may want to clean up your system somewhat:

- Kill the sample app VMs with vagrant destroy.

- Recreate the sample apps (and new databases) with vagrant up.

Application feature design

There are several ‘standard’ user-visible features related to account and session management, and we’ll be implementing/securing them in some sample apps later on. But before we do that, let’s take a moment to consider the bigger picture.

If you are building a system to launch nuclear missiles, you might want quite a secure authentication process, so as to avoid embarrassing incidents.

On the other hand you might find Gold Codes a burdensome solution for launching a tweet about what your cat had for breakfast. Security is only one concern in application design, alongside others such as usability and performance, and there is always a trade-off to be made. Where you place that trade-off is essentially a business decision and depends on what your application is for and why you are building it. So as a developer it’s not entirely your call.

However (and this is a big one) security is a bit different:

- Security risks and the mechanics of attacks are not widely understood, which makes agreed prioritisation difficult.

- Business/management priorities have a habit of changing rapidly when Something Bad happens, and when the blame game starts, the developers will be finger-pointing magnets.

So this means that as a developer you have to

- Understand security risks and the mechanics of attacks, and be able to explain them clearly to a non-technical audience

- Involve yourself in application design, not just implementation

- Be prepared to push back on business requirements, in a professional and constructive way.

The building blocks

Returning to the account and session management features - login, logout, registration, password reset, etc - there are common themes running through all of them, so let’s now take a look at some of the common issues and solution elements.

User IDs

There is a design choice here - where to use email addresses as user IDs, or to keep them as separate entities, and the choice comes with usability trade-offs to consider in the context of your specific application:

- Email addresses are unique, user-generated names (e.g. fred1) are not, so there is some additional UI and implementation complexity to use user-generated names.

- Email address often contain real-world personal names, and are generally traceable back to individuals, so there may be privacy issues in using emails.

- Using the same user ID (your email address) for multiple sites makes your user ID very guessable, so users may want to have different IDs on different site, to reduce their vulnerability to brute-force attacks.

- People sometimes change their email addresses, or have more than one and want to change which one they use, but may not want multiple accounts on your site.

- It’s generally easier to forget an arbitrary user name than it is to forget your email address, so they are less convenient.

- Email addresses can be used in many of the authentication patterns described below, as a secondary channel for verification, so we may need email addresses even if they aren’t the primary user ID.

The bottom line here, as usual, is that it depends on your application. You have to make a choice, picking the right balance of usability and security for your business case. There is no single right answer.

In the sample apps in the accompanying git repo, we use email addresses as user IDs.

One interesting wrinkle that applies to some of these issues is that some email providers (e.g. gmail) allow addresses to be modified with the addition of dots and suffixes while still resolving to the same address, so (e.g.) rufustfirefly@gmail.com is the same account as rufus.t.firefly@gmail.com or rufustfirefly+grouchomarx@gmail.com. See http://gmailblog.blogspot.co.uk/2008/03/2-hidden-ways-to-get-more-from-your.html for the details. Not everyone uses gmail, of course, so you can’t rely on it, but it does at least allow some users to have unique and arbitrarily unguessable IDs while still allowing the site to use their ID as an email address.

Passwords

A good password should be:

- Unique - not used elsewhere, by anyone

- Difficult to discover by guesswork

- Difficult to discover by enumeration

Happily, while in principle the user chooses his password it is possible to help him to choose one that meets those criteria. Apart from general advice such as “Use a password manager” and “Don’t use ‘P@55w0rd’” you can implement some functionality in the UI to help him:

- Don’t restrict password length. Every additional character in a password multiplies the size of the search space to guess the password by the number of possible characters - i.e. a factor of between 50 and 100 for upper and lower case ASCII + numerals and a load of special characters. You don’t have to worry about database storage because you should be storing hashes, which are all the same length regardless.

- Don’t restrict the allowed characters. You don’t have to worry about XSS, because you are never going to pass the user’s password back from the server to his browser, and you don’t have to worry about SQL (or other) injection attacks because you a re going to hash the password before you store it anywhere. See password storage below for both of these.

- Provide visual strength feedback - e.g. the red/yellow/green bar. Some (maybe spurious?) percentage figure will also motivate a certain type of user.

- Consider more sophisticated server side validation of passwords - e.g. Some organisations check existing password hashes against lists of compromised passwords. This is a more targeted way of ensuring that the same password is not used twice.

- Allow paste on password fields. There is no reason to prevent this, and doing so makes life hard for your savvy user who uses a password generator to create a strong string of alphabetti spaghetti like this:

pMU9hxg650ec%^B8^o7$%LPaHz5al9tB6Z0AqosL@*lcFqmDoEhSXbAp*y2rFRtypsp7kbwahdxFZr72

Out-of-band authentication

This is a design pattern where authentication conversations are split over more than one communication channels - typically web application + email, or web application + SMS. This pattern improves the security of the authentication process by requiring an attacker to subvert more than one channel. It is closely related to Two-factor authentication.

Typically, it works like this:

- The user performs some action, e.g. registration

- The site sends him an email with a URL or a text with a numeric code

- The user clicks on the link or enters the code

This verifies that the user is genuinely entitled to use that email address or phone number. An attacker would also have to have compromised the user’s email or phone, which clearly makes his job a lot harder.

Two-factor authentication

This is a design pattern where authentication depends on more than one form of credential - typically password + a generated token, or password + a pre-defined answer to a secret question. This pattern improves the security of the authentication process by requiring additional credentials that are not compromised along with the password. It is closely related to Out-of-band authentication. In general you should be able to find canned 2FA solutions, rather than writing all of this from scratch.

The second factor can take many forms, often extending the “something you know” password credential with a “something you have” element - a phone maybe, or an RSA key, or the PIN validator devices supplied by many banks, or an email account. There is a clear usability trade-off here - if the user loses the ‘thing’, or just doesn’t have it to hand, you have unintentionally denial-of-serviced them, and they will see it that way, as your fault, not theirs. If an attacker manages to get hold of the ‘thing’ it’s worse, and they will still see it as your fault.

Verification (secret) questions are not a very strong defence, partly because the questions and answers need to be stored along with password, and are equally vulnerable to data breach. That aside, there is also the major problem that it’s hard to think of questions that have unambiguous answers that are not easily discovered or guessed by an attacker. Don’t ask questions with publicly available answers - the more information users make public about themselves, the harder this is, and in the social media age no one really has secrets any more. Don’t ask questions with easily guessable answers - e.g favourite colour. The questions should be concise, specific, unchanging, and easy to automate checking the answer. You should provide many possible Question/Answer pairs, and avoid allowing the user to define their own questions - this would allow unwary users to set questions like “What colour is the sky?”. Like the password strength discussion, you should be trying to protect users who are not aware of the consequences of poor security-related behaviour.

Another issue with secret questions is that your site needs to store the secret answers. This poses you the same problems that you face with password storage. Techniques for password storage are discussed below, but it’s plain that there is little difference between “My password is ‘P@55W0rd’” and “My first pet’s name was ‘Gromit’” - both are privileged user information that must be protected against disclosure.

CAPTCHA

The basic purpose of a CAPTCHA (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) is to provide a step that cannot be automated (though see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CAPTCHA#Circumvention). One downside of this is that CAPTCHAs annoy many people.

Time-limited single-use nonce

The term ‘nonce’ in its technical sense means a number that may only be used once. So far as the number itself is concerned, this implies that they are unique - you never get the same one twice. But the single-usage requirement depends on what you do with it. In this context, it’s a key element in a mechanism for ensuring that a particular operation is only performed once, and that the operation is performed within a specified time frame.

Identity as a service

If you have got this far, and if you carry on into the practical sections below, you will see that there is a lot of work involved in setting up a secure account management system, and many ways to get this wrong. Furthermore, it probably doesn’t really have much to do with your application’s unique selling point, and there will be a lot of repetition from one application to another.

The obvious thing to do here is to make it Someone Else’s Problem, by using some form of identity-as-a-service solution. The basic premise of these is that you trust some third party to handle everything to do with authentication, registration, passwords etc. Widely diverse identity services such as Azure Active Directory, OpenID connect, login with Google etc. provide this kind of functionality. This should not be confused with single sign-on solutions, which have similar implementations, but address a slightly different use case - though the two are often combined.

While this kind of solution has enormous attraction, there a few down-sides to consider:

- To gain the full productivity advantage you would have to not implement any authentication yourself, thus possibly requiring the use to sign up with other services, which they may not want to do. You would also put yourself entirely at the mercy of those services, in terms of cost and availability. If you also provide your own authentication, it still has to be appropriately robust, as described at length below.

- Treating identity services as a black box means that your developers may not have so much idea of exactly what they’re delivering. Presumably a reputable service will provide a secure solution (it’s their main business, after all) but it may not be tuned to your particular needs. It’s easy to follow the vanilla integration instructions and move swiftly on to the next work item, which is a problem if vanilla is not what you want.

- Many (most?) users are baffled by a wide selection of possible login choices, and don’t necessarily understand what it is they are choosing. This tends to get them into the habit of blindly clicking on the “Yes, whatever” button, which is not really a great attitude as more of their lives are conducted online.

If identity as a service is the way you want to go for your application, the rest of this article will be of interest in terms of understanding the issues, and for your behaviour as a user of other sites, but you probably won’t want to do the practical exercises.

Securing the sample applications

The two sample applications (MEAN_stack and Jade_Express_MySQL) in the accompanying git repo both provide very basic and insecure features for registration, login and log out. In the following sections we will update these samples with more secure implementations and good practice.

The sample apps are both implementations of a very simple social media platform. Any logged in user can post a message, which will be tagged with their username and displayed to anyone viewing the site, logged in or not. That’s pretty much the whole spec.

1. Do password storage right

The sample apps store passwords in plain text. This makes them completely vulnerable to exposure as a result of exfiltration via an injection attack or any other form of data breach - e.g. cases where the servers are left unsecured against remote log in, or cases of unauthorized internal access.

Important. You are entrusted with other peoples’ secrets. You should be taking this very seriously.

So, how do we store passwords securely? Clearly, plain text is no good at all - the password strength is irrelevant if the attacker can read it. Reversible encryption is no good either, because once an attacker has the encryption key he can easily decrypt all the passwords, and key management is not easy. Both these solutions allow the password to be recovered from the system and output to the user, which is superficially attractive, but in fact a whole bunch of unnecessary vulnerabilities, particularly when the password is sent to the user via email. SMTP is not a secure protocol, and this practice results in plain text passwords being stored on a variety of servers and visible in transit. There is a name-and-shame site dedicated to this anti-pattern here: http://plaintextoffenders.com/

In any case, as we will see below, your site does not need to ‘know’ a user’s password, it only needs to check it. It is perfectly possible (and desirable) to implement account management features so that they don’t pass passwords to the user in any form. This is done by using a hash algorithm, a non-reversible mathematical process that maps arbitrary input to a fixed size value. The password is hashed and the hash is stored. Password checks are done the same way, by hashing the password and comparing the result against the stored hash.

The problem with this is that while the hash algorithm is non-reversible, it’s possible to guess passwords, and hash them. If the attacker has obtained the hashed passwords somehow, it’s not that hard for him to crack the hashes, and there are many sites that do this for you in various ways, as a search for ‘hash crackers’ will confirm. In the simplest case, the attacker would pre-compute hashes for a long list of potential plain-text passwords, and compare the stolen hashes with the computed ones. In reality, this would be an expensive and inefficient way to proceed, so more sophisticated techniques such as rainbow tables are also used. This technique is described here, but sadly it’s a lot less fun than this:

The (partial) defence against this is to hash with a salt value - a piece of random data added to each password prior to hashing. Salting makes it somewhat harder to crack individual passwords, either by computing hashes on the fly or by using pre-computed rainbow tables, but a lot harder to crack passwords in bulk, as they effectively make the passwords stronger and unique.

Don’t write your own hashing algorithms (or any other crypto functionality), that’s work for specialists. Use a strong publicly accepted hashing algorithm such as SHA256 (not SHA1, it’s obsolete) which can easily be future-proofed against increasing hardware power.

Practical Now update the sample apps, using the bcrypt library to hash and compare the passwords, and changing database schemas as necessary. Bcrypt uses salts and can be tuned to work slowly (many rounds of hashing) - this is a good thing, as it increases the cost for the attacker of trying multiple password guesses. Note that bcrypt is not necessarily the best choice in all cases, and your choices may be limited by regulatory compliance.

Practical So, we’ve now fixed the case where we’re deliberately storing passwords, but the sample apps have another weakness - the log files. By an ‘accidental’ oversight, the apps log the entire HTTP request, so the user’s password ends up in plain text in a log file, and any backups etc. It may (should) have been transported via HTTPS, so was secure in transit, but this is irrelevant once it gets into the servers. Review the logging of the sample apps and fix them so that you only log the following: logged in identity, IP address, requested action, timestamp, user agent, referrer. This will also defend against accidental disclosure of session tokens. Also review the logging of exceptions and ensure that no credentials or other sensitive data is logged.

Further reading: see https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Password_Storage_Cheat_Sheet

2. Redesign and build the user registration feature

The basic use case for this feature is that of a new user who is not already known to the system and wishes to create an account. In this scenario, we cannot apply the usual authentication techniques, because the user is, by definition, unknown to us.

For the same reason, it’s not immediately obvious what ‘useful’ attacks could be mounted against the registration feature - you can’t abuse an account that doesn’t even exist, right?

Wrong.

- An attacker could create an account in a user’s name and cause him reputational or financial damage. e.g. Ashley Madison (yes, those guys again).

- An attacker could determine whether a user has an account, by attempting to re-register you, and follow this up by a password-guessing attack.

- If your site sends confirmation emails (see below) an attacker could cause it to spam the world by registering many new users, causing spam-reputational damage to the site.

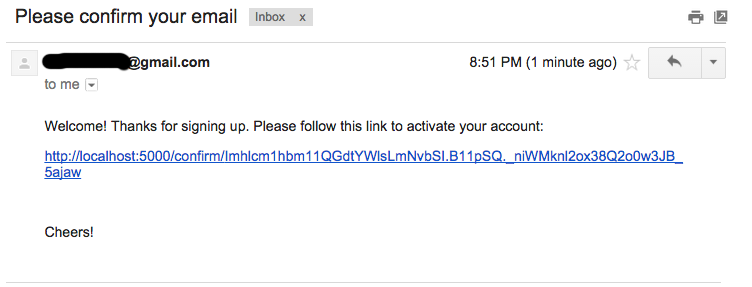

The simple defence against the first attack depends on the site having access to the user’s email address (whether or not it’s actually the user ID). On receipt of the registration request the site sends a confirmation email to the user, typically containing a URL with a time-limited single-use nonce attached as a query parameter. On receipt of this the site completes the request. The attacker doesn’t get the email (assuming he hasn’t also compromised the victim’s email account), and even if he manages to get hold of a copy of the URL later, the nonce has expired and/or been used. Here’s an example:

The same process also defends against the second attack. I didn’t mention this in the previous paragraph, but it is important that the application’s UI displays a non-revealing message to the attacker/user - something like “Your registration request is being processed and a confirmation message has been sent to…”. The point here is that the message in the website gives nothing away about whether the account already exists or not, but the email tells the genuine user the whole story, as well as alerting him that someone is trying to do bad things to him.

The third attack is a problem when the attacker can automate registration requests. If this is likely to be a problem, a CAPTCHA may be appropriate.

Practical Extend the existing registration feature on the sample apps by implementing the first defence above. There’s no need to implement it with emails as such - this would be a load of unnecessary work for a learning exercise - writing to the browser console is sufficient. In order to make this work with a single-use nonce you will have to maintain state on the server, and given the transient nature of the nonce data this might give you some architectural decisions to make, but in the samples, use the database.

Optionally, you might also add a CAPTCHA to the sample apps.

Practical Now add a password strength indication control to the registration page, as described in the section on passwords above.

You’ll notice that I’m not suggesting you implement a ‘secret question’ or password hint feature. That’s not an oversight.

3. Redesign and build the login feature

The basic use case for this feature is for a registered user to authenticate himself with your site. He must present some set of credentials which the site can verify.

There are some very obvious attacks against this feature, and some less obvious ones:

- Brute force guessing. The attacker makes many login attempts

- Obtaining the password by other means - e.g. injection attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, social engineering, etc. - and logging in directly

- Discovering where a user has an account, without actually logging in

One defence against the first and third attacks is to ensure that the failure messages don’t give much away, and particularly that they don’t tell the attacker whether the user name was wrong or the password. The message should just be some polite version of “No”. By telling the attacker “That user name doesn’t exist”, or “You got a valid user name but you still need to guess the password” you have drastically reduced the number of guesses he will need for a brute force attack.

However, if the site uses email addresses as user IDs (most do) this doesn’t help much as a defence for a brute-force attack on a known user, and many such attacks use automation to make a huge number of login requests, sometimes using botnets, with requests coming from many different IP addresses. One possible defence against these automated attacks is to attempt to throttle login requests by making the responses slower after each failure. A botnet will use many different IP addresses, so throttling by IP address won’t work, you have to track the number of login attempts per account. This has to be done server-side, and so requires infrastructure - doing it with a cookie is no good, as automated headless attacks aren’t going to use a browser. Hopefully you will be able to do this with framework features, or some third-party solution. Locking the user out entirely after a number of failures is a bad solution, because it allows the attacker to run a denial-of-service attack, systematically locking out users. You should also log all requests (see the password storage section above) and consider putting in place additional monitoring and defence with web application frameworks such as cloudflare.

The second attack bypasses all the above defences, but 2 factor authentication provides another mitigation. However, as described above, this carries a usability trade-off and it only makes the attacker’s job more difficult, not impossible. Any practical use of 2FA is likely to include human-operated fallbacks for when a user is unable to operate the 2FA process (maybe they lost their phone or whatever) and these channels can of course be used by an attacker as well as by a genuine user.

Practical Ensure that the error message presented by the login UI do not indicate whether the user name or the password is incorrect.

Practical As with the previous section, use the browser console as a 2 factor authentication channel, as if a short numeric code had been sent to the user via text.

4. Implement a robust session management scheme

In the first article in this series I briefly apologized for conflating session tokens and authentication tokens - it was a simplification to make the discussion of transport layer security easier. In this article we’ll dig a bit deeper, and the first step is to explore some concepts involved.

- Session. An ongoing conversation between client and server

- Identity. A very elusive philosophical concept, and one that is a bit too debatable for use here. Is rsillem@scottlogic.com the same identity as robin.sillem@someemailprovider.com? That depends on who’s asking and why, I reckon, so lets use something a bit more formally defined:

- Principal. An independent entity that can be authenticated (Hmm. Sounds like we’re getting into a circular definition here…). A principal may or not represent a person, and you may or may not know who that person is. A principal has some associated identifier - an immutable and unique piece of data.

- Authentication. The process of checking that a received request came from a specific principal. This is another really hard problem, because it’s basically a question of trust. If I say to you “I am Spartacus”, you’ll probably laugh and say “No, I am Spartacus”. If someone you trust (take a moment to unpick what that actually means) then tells you “No, he really is Spartacus”, you’re going to think something funny is going on. If I then show you a passport - i.e. present my credentials - in the name of Spartacus with a picture that looks like me, you might be convinced enough to tweet about it, but not enough to lend me £100,000 - maybe the passport is forged, maybe that’s not me in the picture. And anyway, isn’t Spartacus supposed to be dead?

- Authorization. Granting different access to behaviour/resources to different principals. Now we’re back on slightly safer ground.

It would be nice to say that clarified matters, but the longer you think about identity and authentication the slipperier it all gets. It is always a case of picking some arbitrary protocol by which you can sufficiently assure yourself that you should honour the request, depending entirely on the needs of your application. So let’s consider the requirements of the toy social media site implemented in the sample apps.

The problem with this app is that it is just too simple. The anonymous user scenario has no behaviour that requires a persistent session - it’s just viewing all incoming posts, and there is nothing to remember between HTTP requests. Now let’s look at the architectures as they stand:

- The MEAN_stack sample is entirely stateless up to the point of login, when a JSON Web Token is created with the user name. This JWT is a token for the successful authentication, and the client has the responsibility of holding on to it, and presenting it to the server when it wants authorization to post a new message, for example. There is no real concept of Session here, just authentication.

- The Jade_Express_MySQL sample creates a session cookie whenever it gets a request that doesn’t present a pre-existing session cookie, regardless of whether the request comes from a logged in user. This session ID provides a key into server-side session storage, though the app doesn’t actually use this until the user logs in, at which point his username is stored. So in this case, authentication state is just an attribute of session state.

The stateless, token-based approach taken by the MEAN_Stack sample is more modern, and deals better with architectural issues such as scalability, but also has various security pros and cons, which we’ll address shortly. The specific session management design of the Jade_Express_MySQL sample has some security problems, however. Consider what happens to an anonymous user who visits the site. Let’s assume that an attacker captures the session ID - maybe the site is served to anonymous users over HTTP, not HTTPS. The attacker can use this session, but it doesn’t help him because he’s not logged in. But as soon as the genuine user logs in, he’s logged the attacker in too. The solution to this is to regenerate the session ID after any privilege level change (i.e. log in and log out), so the hijacked session no longer exists (this also defends against session fixation attacks, where the attacker forces the victim to use a specific sessions of the attacker’s choosing). One good way to think about this is as separate conversations:

- Conversation 1, between unknown user and the site. Session ID: 56392476394625342

- Conversation 2, between a.user@foobar.com and the site. Session ID: 87359561048350238

- Conversation 3, between unknown user and the site. Session ID: 12399372621450654

Practical Fix the Jade_Express_MySQL sample vulnerability by regenerating the session on login and logoff. Test by manually capturing the session cookie from the first session and trying to use it as an attacker when the real user has logged in.

N.B. Those session IDs above are just numbers I typed in ‘at random’. Be very careful if you are rolling your own session IDs (not recommended). Don’t use short IDs, they’re easily enumerable - e.g. if your IDs are 4 digits long an attacker could quickly construct all 10000 possible session cookies and hijack by a brute force attack.

In a more complex application you might consider separating session and authentication state, depending on your requirements. This would allow you (for instance) to have a long-running notion of user identity, but only permit sensitive operations after a re-authentication step. However, there are trade-offs here too. Over-frequent re-authentication is burdensome and annoying for the user, and increases their risk of leaking their credentials by MITM attacks or simply by having other people see them typing.

Digression The architecture of both sample apps makes it possible to have multiple independently authenticated sessions on separate browsers/devices. This may or may not be a good thing in the context of your applications. If you need to be able to remotely log off/ de-authenticate users centrally from all sessions, or actively defend against stolen auth tokens, or if you have an application that might suffer data integrity issues from multiple simultaneous user sessions you may need to consider central tracking of authentication state. However, this will give you a complexity overhead and single point of failure. It’s yet another design trade-off, security vs cost this time, but does allow some nice features, such as emailing the user if a login has come from new IP or machine, maybe with geolocation.

There should be a logoff if there’s a login. Make it easily findable to encourage your users to use it - normally it’s found somewhere at the top right of the window.

5. Add a Remember Me feature

Many sites have a ‘Remember Me’ or ‘Keep Me Logged In’ feature, which as the name suggests allows then to access their account without explicit authentication, even after a client browser/machine shutdown. This is a convenience to users, but it also exposes them to some risk of account hijack, particularly if their device is used by someone else. You will need to make a choice about how appropriate this feature is for your app - e.g. whether it is on by default, whether re-authentication is required for sensitive operations. In some cases you may be able to bypass it simply by holding non-sensitive data in the browser.

In terms of implementation, there are a couple of basic approaches:

Storing and passing usernames and passwords is fraught with problems, starting with password storage, as described above, and is not recommended. There have been some terrible examples of this, with projects being killed as a result of practices such as passing user passwords in plain text on a URL. Better is to manage the lifetime of whatever session/authentication tokens your design uses, and the exact way this works will depend on the technology used.

In the Remember Me case, both cookies and JWTs allow an expiry date to be included, and a long expiry date (e.g. a year) does the job. The exact mechanics are not identical, but the principle is - simply check that the expiry has not occurred as part of the authorization check.

What is not so easy is to design a robust and suitable session expiration system for the Don’t-Remember-Me case (I’m assuming this is the default, but it is a choice to be made based on the requirements of your app). Typically you might want authentication to expire after some period of time, or when the browser closes, but there’s a huge variation between apps and user expectations - whatever timeout you have will be wrong for some people. In your choice, bear in mind the following two attack vectors:

- The attacker gains access to the victim’s machine while it is logged in with a long-running session token or cookie.

- The attacker gains access to a still-valid token by some other means, even if the victim has logged out.

The techniques for implementing this revolve around expiry dates for cookies (including session expiry, where the cookie should expire when the browser closes) and tokens. Fixing these times is a problem as you don’t know how long the user might want to stay logged in for, and so you are likely to have to use some form of renewal mechanism (this is the sort of thing that is built into identity-as-a-service offerings). One gotcha with session cookies is that you can completely override the expiry behaviour with browser settings (e.g. Chrome’s ‘Continue where you left off’ setting).

Practical Modify both sample apps so that the login has a Remember Me option. If this is not checked the user should be logged out after 2 minutes of inactivity (That’s ridiculously short for an app of this type, but OK for learning and test purposes). The user should remain logged in if he keeps interacting without as 2 minute gap.

This is just a very light skim of a complex subject, and you should consult OWASP Session Management Cheat Sheet for more details

6. Account Details Change and Password Change features

If an attacker can gain access to wherever your app presents the user’s personal information, he can use that information either for direct gain (e.g. blackmail, unauthorized purchases, ransom etc.), or to leverage other attacks (as additional credentials, for example). In this scenario, email address is sensitive information, because it may be what the system uses for out-of-band authentication or other forms of verification.

If an attacker can change a victim’s password, he can lock the victim out and make it hard for him to regain control. Even if the attacker does no direct harm to the user, this is a denial-of-service attack against your site.

In either case, it’s worth pointing out that users will be less troubled by additional security on these features, because a. The information is obviously sensitive, and b. they don’t actually change account details or password that often.

There are various attack vectors for this: session hijack, by whatever route (including shared computers), credential theft (including social engineering), Cross-Site Request Forgery. The solution is re-authentication for the duration of the operation, preferably with some out-of-band or 2 factor strengthening.

Don’t ask the user for personal information you have no need for. Many users are very sensitive to this kind of thing.

Separate password change from account details change. Ask for the user’s original password. Notify users of password change by email. Likewise notify about any authentication related events - SSH keys, personal details etc. As well as helping to catch unauthorized access, it also lets your users know that you are taking their security seriously.

Require confirmation of email address change by a separate channel (e.g. text, or offline contact with your company). Some edge cases may have to be supported off-line, so you may end up with human-operated processes that have to be documented and followed.

7. The Forgot Your Password feature

Users forget passwords, and you’re going to have to deal with it. It’s not the same as a password change, because the user is by definition not logged in. This makes the solution similar to the one used for registration.

Don’t: email an existing password to user (the app shouldn’t even have access to the plain-text password in the first place, let alone transmit it over SMTP - that password would be insecure in transit and at rest).

Don’t: generate a persistent new password for the user and email it to user - the same remarks apply as above. It also open a Denial of Service vector, because the attacker can reset, and the user is not expecting it and may not immediately check his email - timing is key, a temporary DOS may log a genuine user out while the attacker has control.

Do email a reset link with a time-limited nonce token to the user. The link allows a new password to be submitted without the old one. Nothing actually happens until the final step.

8. Add CSRF protection

Applications are vulnerable to cross-site request forgery attacks whenever an authenticated user can be tricked into making a request. The simplest case is where the user clicks on some link to the vulnerable site in a different (malicious) site. The browser makes the request with the authentication cookie appropriate for the vulnerable site (that’s how cookies work) and the vulnerable site cannot distinguish this from a genuine request. Long-running sessions increase the risk of CSRF - this should be protected against as part of a defence in depth.

The standard defence is the Anti-CSRF token, or Synchronizer token. Basically this is a token associated with the victim’s session which must be passed explicitly in a request header. As it is not available to the attacker’s site, and is not automatically passed by the browser, the attacker needs to forge it but is unable to do so.

For more details, see:

https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Cross-Site_Request_Forgery_(CSRF)

https://www.owasp.org/index.php/CSRF_Prevention_Cheat_Sheet

Practical Add CSRF protection to both sample apps. Note that some front-end frameworks, such as AngularJS already have it built in, but check the details and test - see (e.g.) http://angularjs-best-practices.blogspot.co.uk/2013/07/angularjs-and-xsrfcsrf-cross-site.html. Use Fiddler to check the tokens are being passed back and forth.

Other good practices and considerations

HTTPS everything. See the first article in this series. MITM vulnerabilities can make some of the defences described in this article ineffective.

Protect against XSS and injection attacks.

Consider additional intrusion detection system or web application firewalls (e.g. http://www.iis.net/downloads/microsoft/urlscan or Barracuda https://www.barracuda.com/ or Cloudflare https://www.cloudflare.com/.

Log appropriately - you should be collecting evidence for identifying attacks, but not sensitive user data.

Further reading

Troy Hunt’s Secure Account Management Fundamental course on pluralsight.com is absolute gold, and provided much of the learning for this article. Thoroughly recommended.