The excitement around the potential of conversational UIs and conversational commerce can give the impression that it is THE solution to everything. However, digital conversations are nothing more than an extra channel through which you might want to engage users. The paradigm should be considered in the same way as all other channels, such as mobile, web and physical presence: as part of a (potentially) broader omni-channel strategy. As I have previously written, that strategy should be based around an understanding of your (potential) users, the situations they are in and the tasks they carry out in those situations, i.e. contexts of use.

Only after establishing this insight is it possible to meaningfully evaluate whether and how a conversational UI might support users’ tasks and contexts. To do this, the relative strengths and weaknesses of the conversational paradigm should be considered in order to establish whether it has a genuine place in your overarching strategy or whether it would be a forced gimmick.

What it does and doesn’t do well

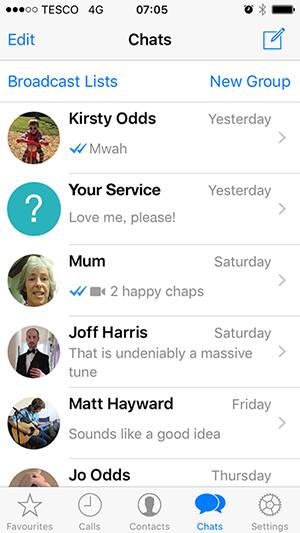

With approximately 3 billion people actively using messaging apps, it’s fair to assume that the basic conversational UI is familiar to anyone with a smartphone. Messaging is inherently personal and direct, so any service with a conversational UI is immediately presenting a similarly personal and direct face, especially when living alongside your existing personal contacts in Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, iMessage or similar. This is both a fantastic opportunity and risk. Get it right and you have a very engaged customer. Get it even slightly wrong, for example by pushing undesired content, and you’ll be shunned as easily and quickly as an annoying friend would be.

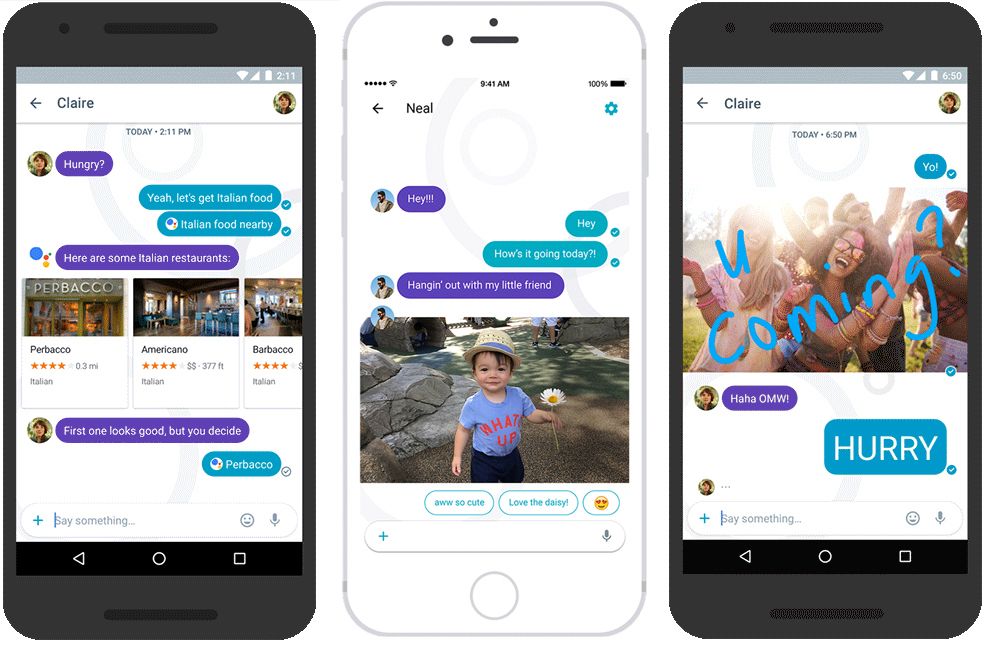

Existing within messaging apps naturally creates opportunities to make your services contextually aware by picking up on explicit or implicit topics in conversation, thereby increasing your services’ relevance and ease of use. Uber is already demonstrating this to great effect, with addresses in conversations being used as potential triggers for ordering transport.

As more of the messaging apps add @mentions, the ability for your services to be brought into discussions will only increase. Even without that level of sophistication, it is still easier for users to switch to a different message thread within the app than to switch apps entirely. Asking your bank-bot for your balance rather than opening your banking app (and going through whatever login process is necessary) is the digital equivalent of peeking at the cash in your wallet compared to walking across the street to a cashpoint. Although this may seem like only a small win in terms of effort, the power of convenience should never be underestimated. Google’s Android Instant Apps announcement earlier this year demonstrates clearly how important convenience is perceived to be.

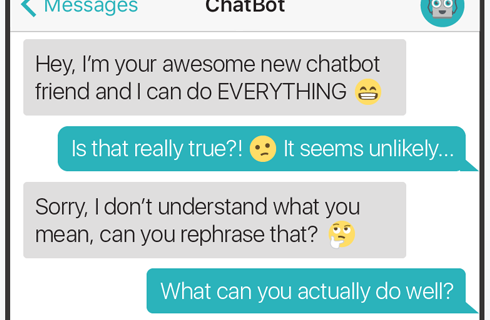

One major difficulty with conversational UIs is that by design they effectively present a blank canvas: we know that we can type/talk to interact with someone or something, but we’ve no idea what we can or cannot do. However, this can be seen as one of the key strengths of conversational UIs: where a typical GUI system for vast or complex functionality will likely be similarly vast or complex because of its adherence to the what-you-see-is-what-you-get (WYSIWYG) notion, conversational UIs leans towards the NUI (natural user interface) paradigm and its idea of what-you-do-is-what-you-get (WYDIWYG).

Importantly, this means a different design mindset. Please don’t carry over GUI concepts such as menu navigation to conversational interfaces. Anyone who has dialled a customer support phone line has experienced the misery of being forced to navigate through menu options in a medium designed for conversation. We all wish we could just tell a person what we’re calling about and get on with things, don’t we?!

This affordance issue is typically mitigated through carefully designed language and, commonly, through the adoption of an anthropomorphised robot, from which the term ‘chatbot’ has arisen. Unfortunately, this term suggests all interactions are driven through conversation – an approach that should likely best be avoided if only because of the almost inevitable ‘uncanny valley’. Ultimately, this issue cannot be entirely eradicated, and there are already suggestions that when presented with a bot, people tend to at worst intentionally ‘troll’ (see Microsoft’s Tay bot), at best unintentionally go off-piste.

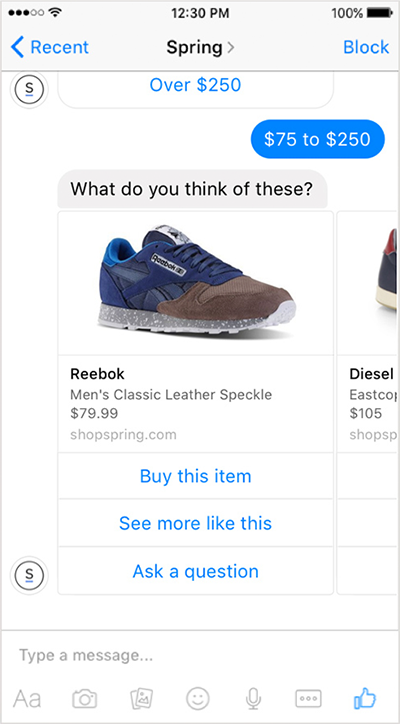

Typing out text is also relatively inefficient. For example, don’t make me type “yes” or “no” to a closed-ended question where some standard GUI buttons or similar would be a lot simpler. Fortunately, the messaging apps are catching on to this issue and are beginning to allow the creation of so-called structured content so that GUI elements can be incorporated into a messaging conversation.

Looking at the bigger picture

Drawing on this understanding of the conversational paradigm’s detailed strengths and weaknesses, it is possible to establish some more general guiding thoughts about the nature of services that do and do not work well with this kind of interaction.

WeChat – the hugely dominant messaging app in China – clearly demonstrates the breadth and variety of opportunities for commerce, big and small, when it is centralised alongside messaging. However, the bot-driven, natural language mechanisms of conversational commerce as pursued by the likes of the Messenger, Skype and Slack actually blends the two worlds of messaging and commerce even more intimately. Unfortunately, the relative infancy of this concept mean the exact manner in which these services are best delivered is still being explored.

It is clear that existing digital services do not necessarily translate well into a conversational UI without significant re-thinking. For example, the existing e-commerce or other search-based service mindset is unsuitable simply because large lists of results cannot be meaningfully displayed in the conversational bubble format. Even with carousel-type structured content, options presented to users should be limited to a handful at most.

To re-orient ourselves, we must consider how we would design the service if the interface was a (super-powered) person. Typically this results in some kind of personal assistant type role, where they might be a lackey to run errands for you, an active part of day-to-day life, an occasional guru to call upon or someone lurking in the shadows keeping sight of your long-term interests. These services take care of menial tasks for you, have an opinion (you trust and agree with!) about matters and make helpful suggestions.

Making it real

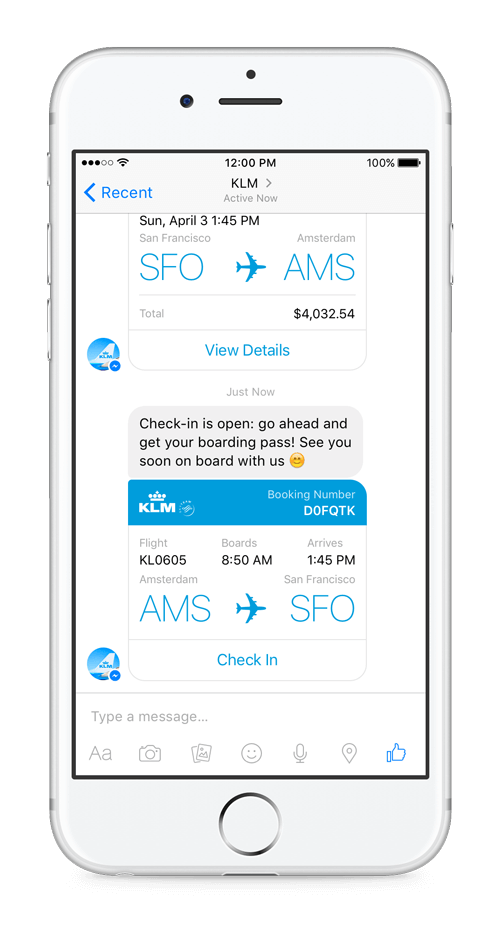

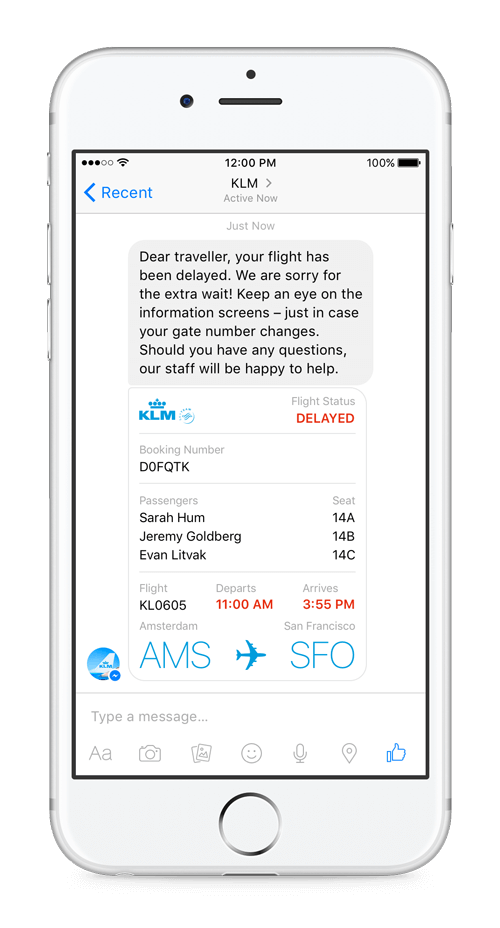

KLM are a high-profile example of an established service that has successfully added a conversational UI as part of its broader strategy. As part of its booking flow, users can opt to receive their boarding pass, flight information and various reminders through Facebook Messenger. Furthermore, they can ask questions and make requests such as changing seats through the same interface.

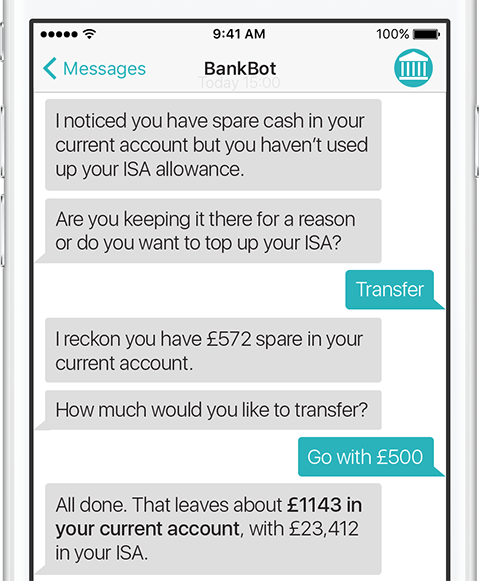

Here at Scott Logic, we have been exploring how banking might add to and enhance its services using conversational commerce. It has highlighted how drastic the change in relationship between service and customer could be using this paradigm, to the extent where it can seem like an entirely new and different service of which the conversational element is only the tip of the iceberg. For example, our savings nudge concept requires some reasonably sophisticated analysis and tracking behind the scenes, but presents itself naturally as a personalised financial advisor:

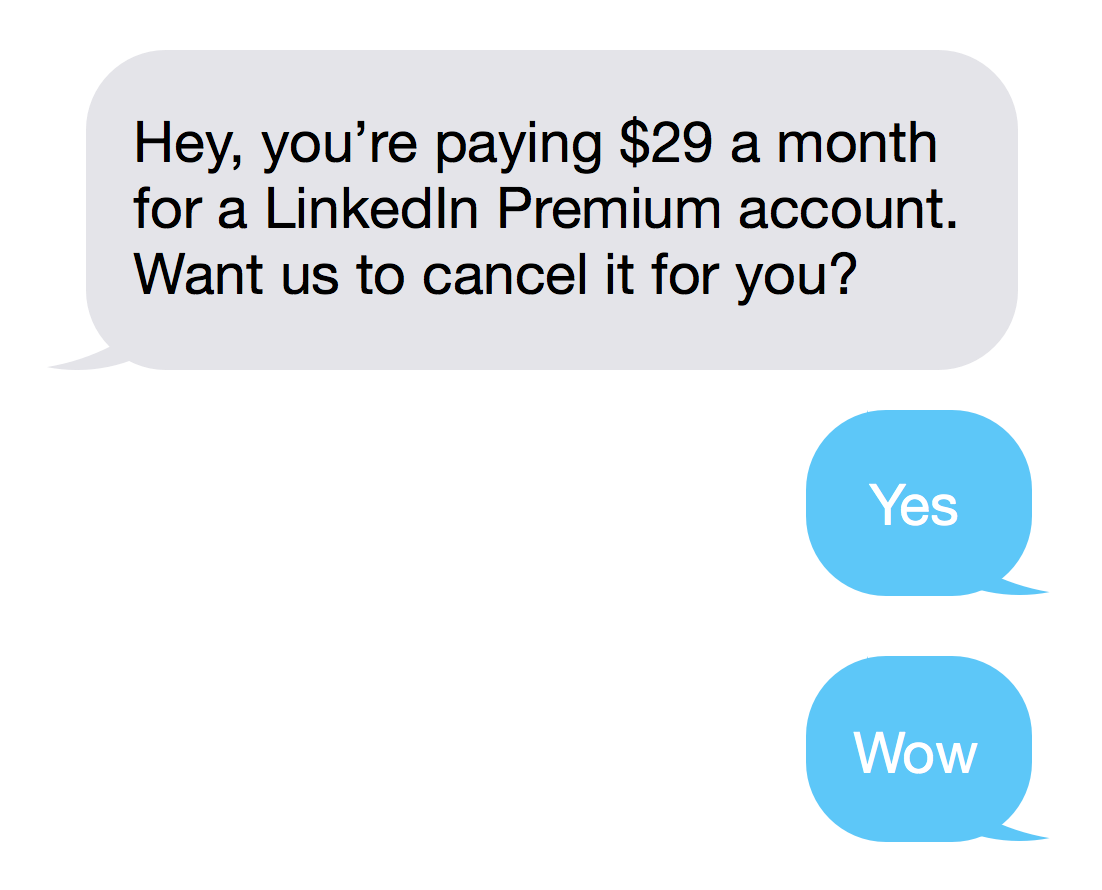

X.ai and Trim are good examples of whole new services that use a relatively simple conversational interface to front sophisticated back-end behaviour. The former allows you to offload the tedium of scheduling meetings by doing little more than CC’ing an email address and then letting a bot exchange emails with the other person. The latter seeks out your paid subscriptions for you, asks whether you want to maintain it or not and then, if desired, cancels it on your behalf; making a tedious task many of us ignore, to our financial detriment, trivial.

Think. Don’t chase technology.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella’s unveiling of the company’s vision of “conversation as a platform” in amongst the flurry of major messaging applications opening up to 3rd party integrations was a clear signal of the gold rush occurring around conversational commerce. The potential of conversational UIs is undoubtedly significant, but, as always with technology hype, it pays not to get blindly swept along with a trend. Take the time to properly understand and explore the technology in question to establish if and how it might be of use to you.

If you would like our help to understand and explore how conversational commerce might be relevant to you, do get in touch.