Introduction

One of the key principles of microservices is that it should be possible to deploy microservices independently. This allows us to avoid the painful ‘big bang’ releases which were common for monoliths and move towards Continuous Delivery. Adopting a Continuous Delivery approach is beneficial because it allows us to deploy features and bug fixes regularly.

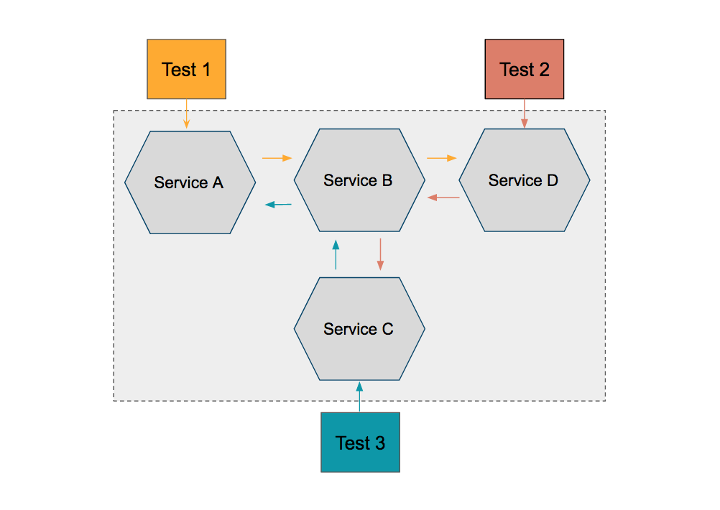

One of the difficulties with achieving independent deployment is that as a system grows the number of dependencies between services increases rapidly. In order to deploy one microservice you need to know that you haven’t broken others downstream.

A common approach to this problem is to have integration and end-to-end checks which ensure that the system still works as a whole. Unfortunately these are often slow, unreliable and hard to debug. Ideally we’d like to check our microservice in isolation which would greatly reduce the complexity .

One way to reduce dependence on integration checking is to use Consumer Driven Contracts or CDCs. The term consumer in this context refers to any service which uses the API of another. Conversely services which provide an API are called providers. A CDC is a form of specification by example that is provided by consumers to providers. The specification usually consists of a set of requests which can be sent to the provider and details of the expected responses.

For example, a CDC may specify that calling the users endpoint should return a JSON object containing a list of users. It could also specify that the user object should have at least the firstName and lastName fields. If the CDC was run against the provider and it instead returned a list of users with a surname field then the check would fail and the developers would know that there was an issue.

Different CDCs can specify different requirements for the same provider, for example another CDC may specify that a lastLogin field should be present. In the future if the provider team wanted to deprecate the lastLogin field then they would know which team to speak to.

Running these checks doesn’t require a running instance of the consumer services which makes them much quicker and more reliable. They can be introduced into the Continuous Delivery pipeline to give greater confidence that things are working before deploying into production.

Pact framework

It is possible to use CDCs without having a framework however there are some great ones available which help you get up and running quickly.

Probably the most commonly used framework at the minute is called Pact. This framework supports a wide range of languages including Java, JavaScript, .net, Ruby, Go and Swift. It can even work for providers written in any language using a command line tool.

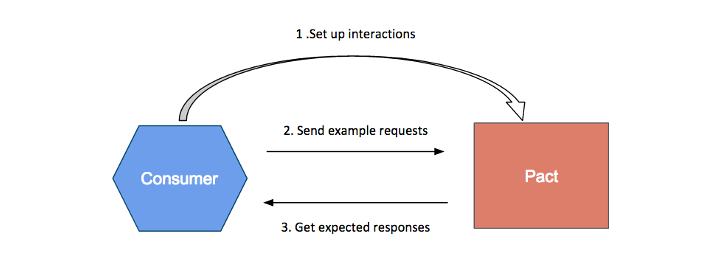

From a consumer perspective Pact acts as a mock HTTP server. The team that owns the consumer write a set of tests which exercise their code against the mock server and set up expected results from the provider.

Pact records these request/response pairs and uses them to generate a contract. The contract consists of the requests sent by the consumer and the required responses from the provider.

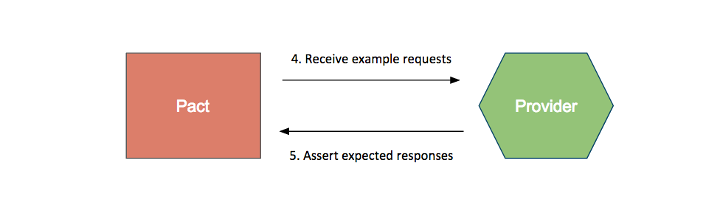

To verify this contract is fulfilled Pact replays the consumer’s requests against the provider API and ensures that the responses match those expected.

Using Pact JS

An example can be helpful to demonstrate the concepts involved. We’ll be creating a simple CDC using the Pact JavaScript library to test the communication between a React application and a backend API.

The frontend application will be created using create-react-app so if you don’t already have this installed globally do so now:

npm install -g create-react-app

Now we can create our example application:

mkdir consumer-driven-contracts-example

cd consumer-driven-contracts-example

create-react-app events-frontend

I’ll be using a Test-Driven Development (TDD) approach with some steps omitted for brevity. This should help show where the Pact code fits into the overall structure of the tests.

First we should create some fixtures to be used by our tests events-frontend/src/fixtures/events-client.js:

const eventOne = {

name: "Event One"

};

const eventTwo = {

name: "Event Two"

};

export const eventsClientFixtures = {

getEvents: {

TWO_EVENTS: [eventOne, eventTwo]

}

};

Using a fixtures file or a factory is recommended in the Pact documentation to help check that there are no invalid mocks used anywhere in your tests. Pact checks that your mocks are correct against the provider but it would be too expensive to use it in every test. Using the same fixtures everywhere ensures that they have been checked by Pact at least once (as long as your fixtures or factories have full coverage). For a more detailed explanation see this Gist.

Pact recommends sending all provider requests through central classes which are tested by Pact. For the Events functionality we will be using an ES6 class called EventsClient.

In order to test-drive the development of this class create a test file called events-frontend/src/EventsClient.test.js with the following content:

import EventsClient from './EventsClient';

import {eventsClientFixtures} from './fixtures/events-client';

describe('returns the expected result when the events service returns a list of events', () => {

it('returns a list of events', async () => {

// Arrange

const expectedResult = eventsClientFixtures.getEvents.TWO_EVENTS;

const eventsClient = new EventsClient({host: "http://localhost:1234"});

// Act

const events = await eventsClient.getEvents();

// Assert

expect(events).toEqual(expectedResult);

});

});

Running this test will give us an error that EventsClient is not defined, so we’ll create that now in events-frontend/src/EventsClient.js with a dummy implementation of the getEvents method:

class EventsClient {

getEvents() {

return [

{"name": "Event One"},

{"name": "Event Two"}

];

}

}

export default EventsClient;

This should give us green tests so now we should refactor to a sensible (non-dummy) implementation. I’ll be using Axios as a http client so install this now:

npm install --save --save-exact axios

Then update the content of events-frontend/src/EventsClient.js to the following:

import axios from 'axios';

class EventsClient {

constructor(options) {

this.host = options.host;

}

getEvents() {

const headers = {"Accept": "application/json"};

return axios({

url: `${this.host}/events`,

method: 'GET',

headers

})

.then(function (response) {

return response.data;

});

}

}

export default EventsClient;

Running this test results in a Network Error since there is no server at http://localhost:1234 (assuming you don’t have anything running locally on that port). This is where Pact comes in, during the tests we’ll start up a Pact server on that port and program it to respond to our expected requests with the correct responses. We will then generate a Pact file containing this configuration which can be run against the provider service.

Install the Pact Node library using npm:

npm install --save-exact --save-dev @pact-foundation/pact-node pact

We’ll need to add quite a lot of code into events-frontend/src/EventsClient.test.js to configure the Pact server, however, before we introduce Pact there is one important change which needs to be made. As explained in this issue when using Pact with Jest you need to set the test environment to node instead of the default jsdom in your package.json file.

Since the application was created using react-create-app it is necessary to edit the test script in package.json to read react-scripts test --env=node instead of react-scripts test --env=jsdom.

Also note that switching to a Node test environment currently breaks the create-react-app tests. To fix these we need to change from using ReactDOM and use Enzyme instead:

npm install --save-dev --save-exact enzyme react-addons-test-utils

Updating src/App.test.js to the following:

import React from 'react';

import {shallow} from 'enzyme';

import App from './App';

it('renders without crashing', () => {

shallow(<App />);

});

Now we can add a Pact server called mockEventsService at the top of the file (after the imports):

import Pact from 'pact';

import wrapper from '@pact-foundation/pact-node';

import path from 'path';

const PACT_SERVER_PORT = 1234;

const PACT_SPECIFICATION_VERSION = 2;

const mockEventsService = wrapper.createServer({

port: PACT_SERVER_PORT,

spec: PACT_SPECIFICATION_VERSION,

log: path.resolve(process.cwd(), '../pact/logs', 'events-service-pact-integration.log'),

dir: path.resolve(process.cwd(), '../pact/pacts')

});

Pact uses the log and dir options to determine where to store the Pact files and logs. Note that these directories are set to outside the npm project due to an issue with create-react-app’s default watch settings. If you prefer you can move these directories inside the project, eject from create-react-app and exclude them from Jest’s watch list.

After creating the Pact server we need to add Jest before and after hooks to start and stop it. We’ll keep a reference to the provider in order to interact with Pact during the tests:

var provider;

beforeEach((done) => {

mockEventsService.start().then(() => {

provider = Pact({ consumer: 'Events Frontend', provider: 'Events Service', port: 1234 })

done();

}).catch((err) => catchAndContinue(err, done));

});

afterAll(() => {

wrapper.removeAllServers();

});

afterEach((done) => {

mockEventsService.delete().then(() => {

done();

})

.catch((err) => catchAndContinue(err, done));

});

function catchAndContinue(err, done) {

fail(err);

done();

}

The final step is to set up the individual test with the correct expectations (this replaces our original describe block from earlier):

describe('returns the expected result when the events service returns a list of events', () => {

const expectedResult = eventsClientFixtures.getEvents.TWO_EVENTS;

const eventsClient = new EventsClient({host: `http://localhost:${PACT_SERVER_PORT}`});

beforeEach((done) => {

provider.addInteraction({

uponReceiving: 'a request for events',

withRequest: {

method: 'GET',

path: '/events',

headers: { 'Accept': 'application/json' }

},

willRespondWith: {

status: 200,

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: expectedResult

}

}).then(() => done()).catch((err) => catchAndContinue(err, done));

});

afterEach((done) => {

provider.finalize().then(() => done()).catch((err) => catchAndContinue(err, done));

});

it('returns a list of events', async () => {

const events = await eventsClient.getEvents();

expect(events).toEqual(expectedResult);

provider.verify(events);

});

});

Now run the tests and check the contents of the Pact directory. We should get passing tests and a pacts folder created containing a single Pact file:

{

"consumer": {

"name": "Events Frontend"

},

"provider": {

"name": "Events Service"

},

"interactions": [

{

"description": "a request for events",

"request": {

"method": "GET",

"path": "/events",

"headers": {

"Accept": "application/json"

}

},

"response": {

"status": 200,

"headers": {

"Content-Type": "application/json; charset=utf-8"

},

"body": [

{

"name": "Event One"

},

{

"name": "Event Two"

}

]

}

}

],

"metadata": {

"pactSpecificationVersion": "2.0.0"

}

}

The next step is to code a provider service which can fulfil this contract. I’ll use the Pact command line provider verifier for this (although the Node.js provider verifier could also be used here).

In the root of the project create a new folder for the provider and initialise it as an npm project:

mkdir events-service

cd events-service

npm init

We’ll be creating a simple Express server with a dummy implementation to check our contract is working correctly so install Express into the project:

npm install --save express

Then create a file events-service/index.js with the following content:

var express = require('express');

var app = express();

app.get('/events', function (req, res) {

res.set('Content-Type', 'application/json');

res.send([

{"name": "Event One"},

{"name": "Event Two"}

]);

});

app.listen(3000, function () {

console.log('Example app listening on port 3000!')

});

To run this server a start script to the package.json:

{

"name": "events-service",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"start": "node index.js",

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": {

"express": "^4.14.0"

}

}

The recommended way to run the Pact Provider Verifier is using Docker (if you don’t want to use Docker there are instructions for using Ruby on the project page). To do this we’ll need to create both a Dockerfile and a docker-compose.yml:

FROM node:6.9-slim

ADD . .

RUN npm install

CMD npm run start

api:

build: .

ports:

- "3000:3000"

pactverifier:

image: dius/pact-provider-verifier-docker

links:

- api

volumes:

- ../pact/pacts:/tmp/pacts

environment:

- pact_urls=/tmp/pacts/events_frontend-events_service.json

- provider_base_url=http://api:3000

Now we can run the Pact verifier:

docker-compose build api

docker-compose up pactverifier

If everything works okay you should see a message like the below:

pactverifier_1 | Verifying a pact between Events Frontend and Events Service

pactverifier_1 | A request for events

pactverifier_1 | with GET /events

pactverifier_1 | returns a response which

pactverifier_1 | has status code 200

pactverifier_1 | has a matching body

pactverifier_1 | includes headers

pactverifier_1 | "Content-Type" with value "application/json; charset=utf-8"

pactverifier_1 |

pactverifier_1 | 1 interaction, 0 failures

Since we see one interaction and no failure this indicates that the CDC passed against our dummy provider.

Conclusion

This was a basic introduction to Consumer Driven Contract testing with Pact. Since it is such a fully-featured library there were plenty of topics which aren’t covered here. To keep things simple I haven’t used regular expression/flexible matching or provider states, however, I would recommend looking into these topics and perhaps implementing them as an exercise.

Pact seems like a really useful and well thought-out tool and I would definitely recommend giving it a go if you’re considering introducing Consumer Driven Contracts into your pipeline. Being able to test your mocks and avoid drifting from the real provider over time feels like a killer feature for me.

To learn more about Pact see the documentation or visit the project Slack.