Learning Go

I started learning Go in March 2016. I felt like I had reached a point with software testing where I would not be able to improve unless I started really putting more effort into my coding skills. I had previously written a bit of test automation in Python but I was seeing and reading lots of cool things about Go. I had heard that Go was 25 times faster than Python and I also really liked the Go song.

As this learning was something I was intending to do in my own time so I had the luxury of being able to choose a language with no pressure from my day job. I chose Go.

The first book I worked through was “The way to Go”. However for some of the more confusing concepts (like interfaces) I also used a fantastic book called “The Go Programming Language”. After reading and playing around with the example code in these books, I started writing my own Go code to solve problems on Project Euler

Everyone I spoke to when I said I was learning Go said I should build something that I cared about, something that I wanted to use and that solved a problem for me. They warned that only by doing this would the project hold my interest enough to see it through to the end. I decided that I was going to build a web app to help me practice violin scales. I found that I was frequently googling scales to look up the corresponding sheet music. Also in my violin lessons, my teacher would either play a scale for me to play along with, or play the root note of the scale for me to play over. I thought it would be nice to be able to practice in the same way at home without my teacher being present.

I’m going to explain how I created a web app called GoViolin which does all of this and little bit more.

This walk through assumes you have already installed Go, set up your workspace and have a basic familiarity with coding concepts.

Building a Go Web Server

I wanted to create a web app that would allow a user to pick a violin scale, display the corresponding sheet music for the scale and allow mp3s of the scale or the root note to be listened to.

If you want to build a web server with Go, the best place to get started is with Go’s net/http package. By reading through examples using the net/http package I was able to create my own web server. Don’t panic this is not as hard as it might sound. In Go, a simple web server can be put together with a few lines of code. This is what a web server written in Go looks like.

To start this server, save the above code as server.go, then on the command line either type “go run server.go” which will start the server, or type “go build server.go” which will generate a server.exe which will start the server when it is executed by typing ./server on linux (or double clicking the server.exe file that is created on Windows). Once the server is running, in a web browser navigate to http://localhost:8080 and you will see “Hello World”.

What’s going on here is that in the main function, we are handling any requests made to “/” by passing these requests on to a function called helloWorld. The http package that has been imported contains the function http.HandleFunc() which is taking care of sending all the requests made to “/” on to our helloWorld function. The http.HandleFunc() takes two inputs, the first being a pattern which is a string and the second is a handler (a function that needs a ResponseWriter and a pointer to a Request). In order to satisfy the http.HandleFunc our helloWorld function receives two inputs, the first input is called w and is of type http.ResponseWriter. W is where a response can be sent. The second input to the helloWorld function is called r and this is a pointer to a http.Request (the * prefix indicates that this is a pointer - A Tour of Go explains pointers really well should you need to remember how they work). The r input is the request that is made to the webserver. These w and r inputs could have longer names but the general convention is to name them w and r as they appear frequently and this makes them easier to type. The helloWorld function doesn’t care about r (the request), regardless of what request is made helloWorld is always going to print “Hello World”. The helloWorld function sends the response (print “Hello World”) to w which prints “Hello World” in the browser.

In server.go, the second line in the main function is where the webserver is started. This is another function from the net/http package. This line creates a webserver and tells it to listen on port 8080 and serve requests on port 8080.

Hopefully, you should be able to get a simple web server up and running. Once this is done we can start building on top of this foundation.

Using Go’s Template package to Generate a HTML Page and Adding Some Logging

In my GoViolin app, to transfer information from the backend web server (written in Go) to the front end (html pages using css) I used Go’s html/template package. The way templating works is that a html page is written with place holders for variables inserted into the html with curly brackets around them. Go code then renders the .html page by filling in each of the variables as needed with the variables it has been told to use.

Also because we are starting to do more complex operations now is also a good time to start adding a little bit of logging. Go has a purpose built log package for this.

I’ve built upon on the “Hello World” example to show how it is possible to pass variables from the backend to the front end using html/template to generate a html page. This example uses two files. the first file is homepage.html which looks like this

The second file is template.go which uses homepage.html to generate and serve a web page.

when template.go is executed (either with go run or via go build) and the user navigates to http://localhost:8080 in a browser, the page displays the current date and time which is generated by the backend code using the time.Now() function from the time package. If any fatal errors occur while running the web server, these are logged. Also if there are any errors generated when the template is parsed to generate the html page, these are also logged.

Responding to Requests

I wanted my GoViolin app to be able to respond to a request for a scale and display an image of the scale and also allow the user to play a .mp3 file. This meant that the web app was going to need to be able to hear a request and respond to it. I wanted my web app to:

- Generate some radio buttons.

- Display them on a html page.

- Allow the user to make a selection.

- Respond based on the user’s selection.

For steps 1 and 2, generating the radio buttons and displaying them, I was able to accomplish this using a template and {{range}} to generate a series of radio buttons using values stored in a struct.

For step 3, when the user makes a selection, I wanted to send the user’s selection in a POST request to the back-end. I was able to do this by creating a form and using jquery to submit the form when a radio button is changed.

I have written some code to demonstrate how a web app can respond to a request. This example uses two files, select.html and select.go which are shown below. When this code is run and the user navigates to localhost:8080, the user is asked if they prefer cats or dogs and presented with two radio buttons. When the user makes a selection, the page updates and their answer is displayed.

Lets start by looking at select.html this the template which will be used to generate both pages (the page that asks the user for their input and also the page that responds to their input and displays their answer). The select.html template uses {{with}} and {{end}} tags to define two sections of html code. The html inbetween {{with $1:=.PageRadioButtons}} and {{end}} will only display if the template is parsed with a variable called PageRadioButtons. If PageRadioButtons is not passed to the template when it is executed, then this section won’t appear and no radio buttons will display. The same thing happens in between the template tags {{with $2:=.Answer}} {{end}}. If the template receives a value for .Answer it displays it, if not this section does not display. The radio buttons are generated using {{range}} this loops through all the values of PageRadioButtons and generates the input tags for each radio button. We also want the page title to update depending on which of the two pages is being displayed so {{.PageTitle}} has been added to the template to control this for us. The snippet of JavaScript between the script tags uses jquery to submit the form when the user clicks on a radio button. The form submits its data to “/selected”

The corresponding select.go file contains the web server code. Generating the default page when a request to “/” is received is handled by a function named DisplayRadioButtons. This function generates the page that asks the user for their input. A second handler responds when a request is made to “/selected” and this handler uses a function UserSelected. The UserSelected function is where the users request is read by parsing the form data which has been sent to “/selected”. The http request received by the UserSelected function has a method called ParseForm which when called parses the submitted form, takes all the url values and makes them available as r.Form. The r.Form.Get method can then be used to find out which animal the user selected.

Once the UserSelected function knows what the user has selected, it renders the response page by passing a value for the page title and a value for the answer into the select.html template.

Deploying to Heroku

After building my app I wanted to be able to share it with other people which meant that I needed to host it somewhere rather than running it locally. I chose to deploy my app using Heroku. Heroku is a cloud based platform as a service which supports Go. Heroku also provide a detailed walkthrough of how to get started with Go. There are however some important things to remember when deploying a Go app to Heroku.

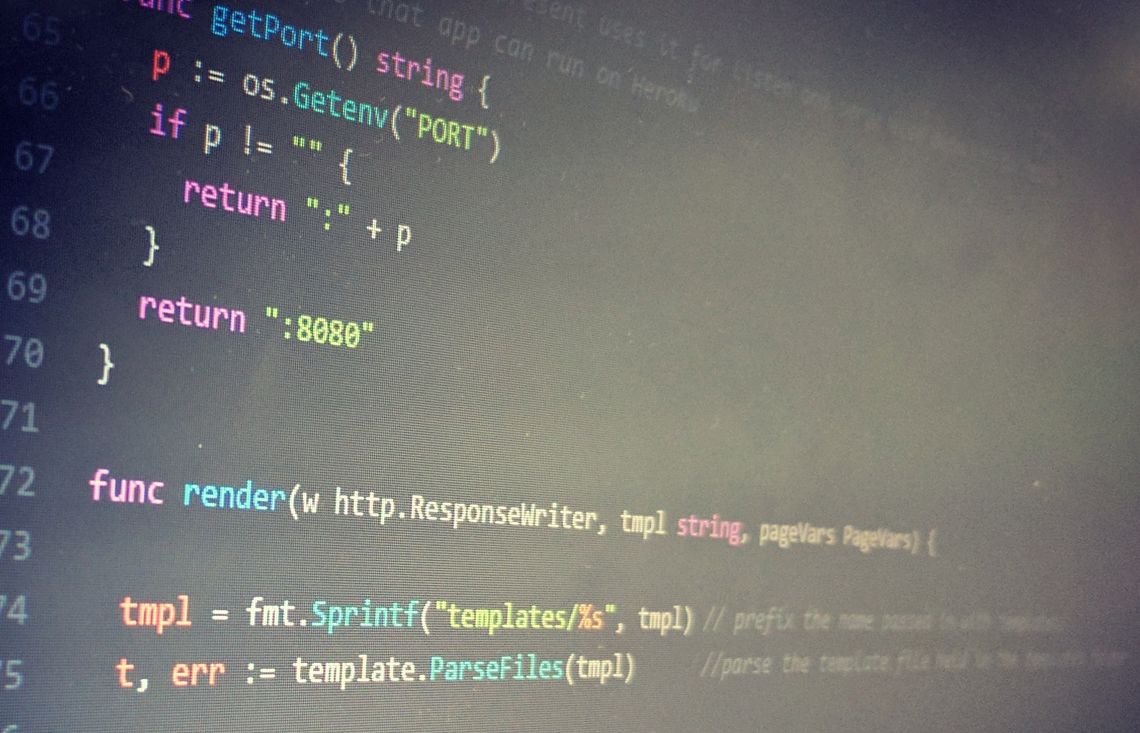

When starting up a go web server inside Heroku, Heroku will assign it a port number. In order for your web server to work, your Go code will need to listen and server on the port number that Heroku gives it. The port number Heroku assigns can be identified using the “os” package and the function os.Getenv(“PORT”). In my app I have used a function to ensure that if running on Heroku, the correct port is used or if running locally port 8080 is used. An example of how to do this is shown below.

It’s also worth mentioning that Heroku identifies native Go apps by the presence of a folder in the project root named “vendor” which contains a “vendor.json” file. If you are not aware of what the vendor folder does, there is a really good explanation on Gopher Academy. For the purpose of my app I was able to create my vendor folder using a package called govendor. Simply typing “go get github.com/kardianos/govendor” installed the package and then while in the root directory of my project typing “govendor init” created the vendor folder and put vendor.json inside it.

The finished Web App

Using web servers, templates, requests and responses I was able to build up my web app for practising violin scales and you can try it out for yourself here. The source code can also be viewed on github.

A Massive Thank You to the Go Community!

While learning Go and working on this project there were times when things got really tough. There were times when I doubted my ability and skill at writing code. I wasn’t sure if I would be able to figure out how to build a web app on my own. I started attending Golang North East, a regular meet up in Newcastle. I have never met another woman at one of these meet ups so when I first started going I did feel a little bit intimidated. I thought that I stuck out like a sore thumb, especially everyone else was a developer in their day job and my day job was in software testing. I was a bit concerned that this group of devs would be prejudiced towards me (sometimes software testing has negativity associated with it and historically some people have seen testing work as inferior to development work). But the months went by and I found everyone at the Go meet up to be very friendly, very knowledgable and also super helpful. I was able to push past my “bunny in the headlights” feeling of not really belonging at development meet ups.

I also joined a Slack group called Gophers on Slack. This is a really large Slack Chat group (at last count over 13,000 members). Again, I felt a bit scared about saying anything or asking questions. Reading the chat left me feeling pretty intimidated. There were so many topics and conversations which were going straight over my head and I felt really out of my depth. I didn’t start chatting straight away on the Gophers Slack. Through Twitter I found out about WomenWhoGo and I was able to connect with them and join their Slack Chat. I have so found the Go community to be incredibly supportive, helpful and inclusive. I am meeting and talking to so many wonderful, passionate people that genuinely care about Go and each other. I’m very proud to be a tiny part of something this awesome.

This post was also published on rosalita.github.io.