Keeping the ‘Hat Shop’ in Business

Welcome to the world’s most popular hat shop. Our database is old and creaky and failing to keep up with today’s demand for our brand new tin foil hats. We need a new, more scalable, solution capable of handling hundreds of order updates per second. We’ll be updating our hat orders so our customers can track their orders with values such as cost, colour and quantity of their desired head gear (our customers are very discerning).

Like comparing Fedora’s and Fez’s…

It’s a foregone conclusion that if horizontal scalability is necessary in a system Cassandra should outperform a traditional relational database. So instead we’ll be looking at how Cassandra performs against MariaDB in a single node setup and how easy it is to use from a development perspective, in particular what the performance of Cassandra is like before we start to scale out.

The Hats

To test our databases, we need some data. We built a system that can generate events as serialised JSON which can be actioned against our databases. We chose standard CRUD operations for our event types, i.e. creating new orders, reading orders, updating the order status and attributes (colour, size, quantity) and deleting orders.

Our Hat Shop relies on Java’s Random library to create a range of events and orders. To ensure that our experiments will be repeatable (that we can run the same data against each database), we seed our random generator so that for each test, it will generate the same set of events and orders.

Generated events look something like this:

{

"type":"CREATE",

"data":{

"id":"4612d1c0-212d-40a0-813d-a17543296896",

"lineItems":[

{

"id":"561cea89-1fd8-4e94-800b-626ca27149f9",

"product":{

"id":"414dfe60-3d7f-445c-8b82-7620f6cea367",

"productType":"HAT",

"name":"Beanie",

"weight":594.81,

"price":6.29,

"colour":"Burnt Sienna",

"size":"XXL"

},

"quantity":9,

"linePrice":56.61

},

{

"id":"cde58d2b-0f60-45d4-b46a-94526f001ec4",

"product":{

"id":"213a29b3-e411-4684-8925-4aca4a1d1e22",

"productType":"HAT",

"name":"Flat",

"weight":168.9,

"price":64.09,

"colour":"Puce",

"size":"S"

},

"quantity":8,

"linePrice":512.72

}],

"client":{

"id":"4612c308-9158-4bbe-bc41-52b25647a2e6",

"name":"Katherine Sims",

"address":"240, frantic Drive, Worcester",

"email":"KatherineSims@fakemail.com"

},

"status":"ORDERED",

"subTotal":2779.22,

"date":1481537772610

}

}…or Cloche’s and Pork Pies

Once we had some data coming in we needed to write the code to handle these events. We made a few design decisions along the way in an effort to make a fairer comparison. We considered, for code-readability and to make database setup easier, using Spring with Hibernate to handle accessing MariaDB data but we opted against this. Instead, for more transparency of how database queries are handled and to ensure equivalency in our testing, we created the database queries ourselves.

We also decided against using the messaging queue software RabbitMQ to send generated events from the hat shop to the databases. Whilst it was useful in allowing us to separate out the data generator code from the databases, fully decoupling the different components of our application, it limited the speed with which we could throw data at the databases. RabbitMQ also had the advantage that it allowed us to play the same events against both databases, however our hat shops seedable random number generator meant that we had this capability already and so we made the decision to leave it out.

The Datastax driver for Cassandra offers asynchronous execution of queries by calling the executeAsync() method. We used Java to run our experiments, so for MariaDB we had to use JDBC for our queries. JDBC doesn’t offer asynchronous execution, so we execute our queries from isolated threads and use a connection pool provided by HikariCP to give use something like the Cassandra driver’s in-built functionality with JDBC.

Lastly we wanted both our databases to be run in an isolated environment which could be easily recreated for testing. To this end we made the decision to use Docker images to run both Cassandra and MariaDB enabling us to run up both database instances quickly and easily. The system however, is written in such a way as to easily allow connections to be made to database instances outside of Docker if necessary.

Logging our results

We wanted to persist the results in a human readable form that was quick to append to and which we could sit a data visualization tool on top of. To this end we logged the following information for each test to .csv files and used Microsoft Excel and PowerBI to produce graphs of our data.

- Test ID

- Database Type

- Event Type

- Time Taken

- Success (If the query succeeded)

- Error Message (If any)

- Time Stamp

We ran tests using identical sets of events and measuring the total times with and without logging, against both MariaDB and Cassandra instances to see if there was a measurable delay due to logging. Indeed, there was a small effect in processing the log, adding between 1 and 5 seconds for 10,000 events but only for our overall time. We are timing each database transaction individually and these timings are not affected by the logger. For tests measuring overall time, logging is disabled.

Thinking cap - Database differences & tweaking performance

Cassandra is a noSQL database, designed to give high performance when distributed at scale. While the database uses terms such as ‘row’, ‘column’ and ‘table’ the underlying data structure is different from a relational database and is more like a Map of Maps. Data in Cassandra is stored at the top level in a keyspace, which is a namespace used to define replication across nodes. Within a keyspace are Column families which are analogous to SQL tables. These map row keys to sorted Maps of column keys and values. Cassandra also ships with its own query language CQL (Cassandra Query Language) which is reminiscent of SQL. The similarities in query language and names like table and row can make it tempting to treat Cassandra as an SQL database when it comes to table design and data query however this can lead to an inefficient approach if you’re not careful, as we found out.

Join operations are not permitted in Cassandra however Primary Keys can be composed of more than one column’s values. The first element in the Primary Key is used as a Partition Key for the table and the others as Clustering Keys. The Partition Key is used to hash the data across the nodes in Cassandra and as such can have a large impact on the efficiency of queries. To maximise efficiency the goal is to distribute data evenly across nodes and to access as few nodes as possible with a single query. This involves structuring the tables in your database in a way that facilitates this.

In Cassandra rather than modifying the data in a table on receiving an ‘update’ query, a new row is created instead. Data in Cassandra is time-stamped and when an update event happens data is written as a new value and the old value is marked with a tombstone and deleted at a later date during the compaction process. This process also helps to increase performance on ‘delete’ events in the same way as Cassandra does not delete the data immediately but simply marks it with a tombstone as with an update.

Tweaking

To ensure that we treated each database as fairly as possible we amalgamated the pre-processing stage of our code such that both Cassandra and MariaDB share as much of the same setup process as possible. Timing is started just before execute is called on each database and stopped once a result is returned. The program remains running until all threads in the thread pool have finished to ensure that we can calculate a reasonably accurate end to end time for the tests. We also made the decision to implement batch statements and asynchronous execution functionality on both databases in order to optimise the queries made on the databases.

Cassandra Tweaks

During the testing process we came across a good example of how the table layout in Cassandra can affect the performance of the database. Our initial tests with ‘update’ events consistently showed MariaDB as being the faster database when processing multiple updates. Cassandra registered times of on average between 10 and 16 milliseconds for transactions to complete. Originally the database tables were similar to the MariaDB tables. An ‘orders’ table and a ‘lineItems’ table. The lineItems table was structured with the following fields:

line_item_id (PK), order_id, product_id, quantity, price

This structure means that the data in the line Items table is distributed across the nodes* in the database using a hash of line_item_id. This is fine for queries on a single line item which require access to just one node but slows performance for querying multiple line items which requires access to multiple nodes.

For operations which require querying multiple line items MariaDB makes use of the foreign key order_id to query all rows with the same order_id. In Cassandra however each line item resides potentially on a separate node and so the query becomes inefficient and functionality to perform such queries is restricted by Cassandra to avoid this. To alleviate this problem the line items table was restructured to better suit Cassandra’s distributed nature and renamed line_items_by_order.

order_id(Partition Key), line_item_id(Clustering Key), product_id, quantity, price

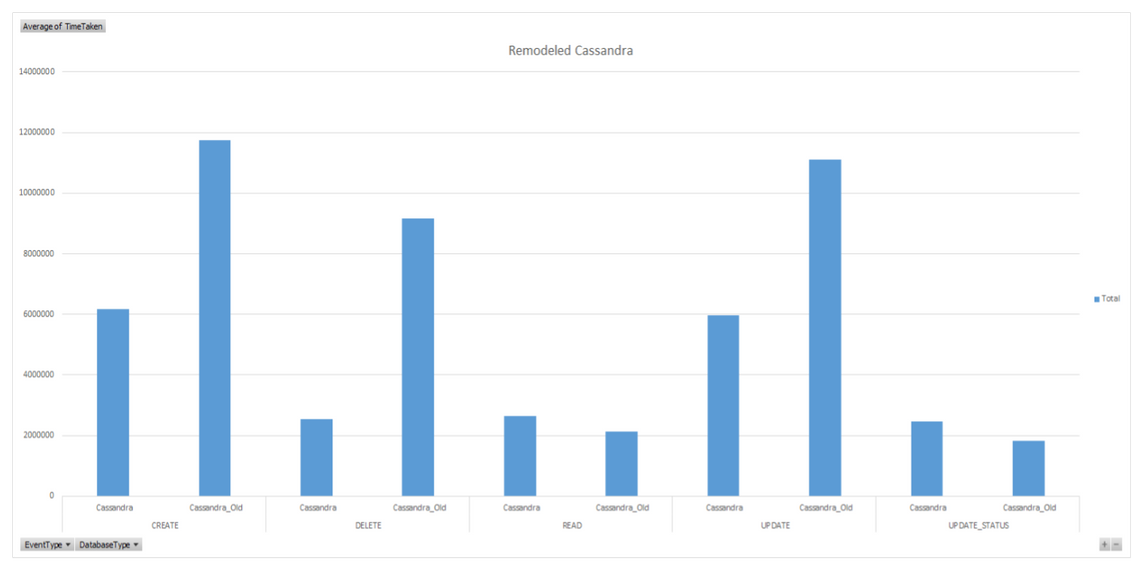

The table now has a composite Primary Key made up of order_id and line_item_id. As discussed the first element (order_id) serves as a Partition Key. This means that now all line items of a given order are stored under the same node in the database, now when a query is made on multiple line items belonging to an order, Cassandra only has to access one node to retrieve all relevant data. Fig 1 shows the times for different queries with the old table style (line_items) and the new (line_items_by_order). As can be seen access times are noticeably improved in most instances.

Fig 1

* Or virtual nodes (vNodes) in our case as we are only using a single node instance

Configuring a Connection Pool for MariaDB

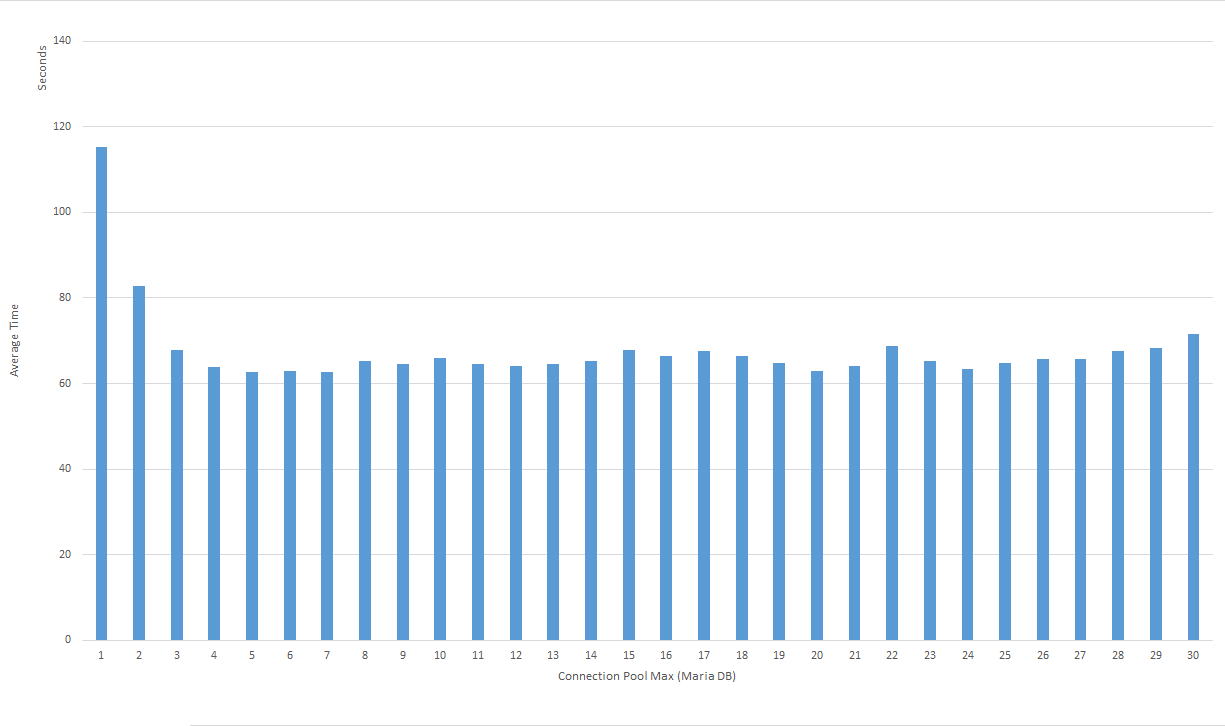

Fig 2 shows the influence of the maximum connections setting on performance in terms of the overall execution time. To produce this chart we took the average of the total execution times of 5 runs of 50,000 ‘create’ operations against MariaDB at each max-connection parameter we tried from 1 to 30.

Fig 2

At a maximum connection pool size of 1, operations are effectively running synchronously, taking nearly 2 minutes to complete the operations. At a maximum of 2, the total execution time is reduced to just over 80 seconds. At 4 we stop seeing the benefit of increasing the size of the connection pool further, achieving an execution time of just over 1 minute.

The connection pool holds a set of threads, each with an independent connection to the database. The machines upon which we’re running our tests have 4 processor cores meaning that at most, we can only be executing 4 threads at once.

Fig 2 shows we could run more, keeping extra threads in memory and switching to them as the cores become free, at no cost to overall time but it would reduce performance in terms of each individual queries response time as the database will respond most quickly when it has the fewest number of clients making requests to it.

Changing hats - how easy is it to update an order?

Starting with the basics, we wanted to know how easy it was to perform the CRUD operations described above.

MariaDB

MariaDB has two tables, orders and line_items set up, respectively, with the following fields:

order_id (PK), client_id, timestamp, order_status

line_item_id (PK), order_id, product_id, quantity

There can be multiple line items to each order. When creating an order, two SQL queries are run, one to create the order and another to create the line items associated with it.

To create a new order:

INSERT INTO order

VALUES('1234-5678-9101-1121', '3141-5161-7181-9202', '1234567890', 'Pending');To add 3 identical line items (primary key is handled automatically) to the order:

INSERT INTO line_item(order_id, product_id, quantity)

VALUES('1234-5678-9101-1121', '0212-2232-4252-6272', 1),

('1234-5678-9101-1121', '0212-2232-4252-6272', 1),

('1234-5678-9101-1121', '0212-2232-4252-6272', 1);To update the order status:

UPDATE order SET status='Out For Delivery' WHERE id='1234-5678-9101-1121';No need to say more about the queries than this, it’s clear enough how they work. This is exactly in line with what one would expect from an SQL database and came together easily. There’s very little to worry about regarding optimising this further, it’s a standard many-to-one relationship.

Cassandra

Setting up Cassandra was also fairly straightforward, we tried both a Docker image running in Ubuntu and the Windows MSI, both allowed a working Cassandra instance to be create quickly and easily with a simple command or double click. Once running we connected to the database using the Datastax Cassandra Java driver allowing us to programmatically create a cluster, session and lastly a keyspace. This again was straightforward with the only issue being to ensure the driver version you are using is compatible with the Cassandra version. Once we were up and running, queries were constructed to setup the database by creating our two tables. Writing queries for the database is almost the same process for Cassandra as for MariaDB, the Cassandra driver supports Prepared statements and Batch statements, and the syntax of the CQL is very similar:

To create a new order:

INSERT INTO order.orders

( order_id, lineItem_ids, client_id, date_created, status, order_subTotal )

VALUES(?, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?);To add line items to the order:

INSERT INTO order.lineItems_by_orderId

( order_id, lineItem_id, product_id, quantity, line_price )

VALUES (?, ?, ?, ?, ?);To update the order:

UPDATE order.orders SET date_created=?, status=?, order_subTotal=? WHERE order_id=?;As can be seen, from this perspective there is no extra effort involved in querying Cassandra vs MariaDB.

Results

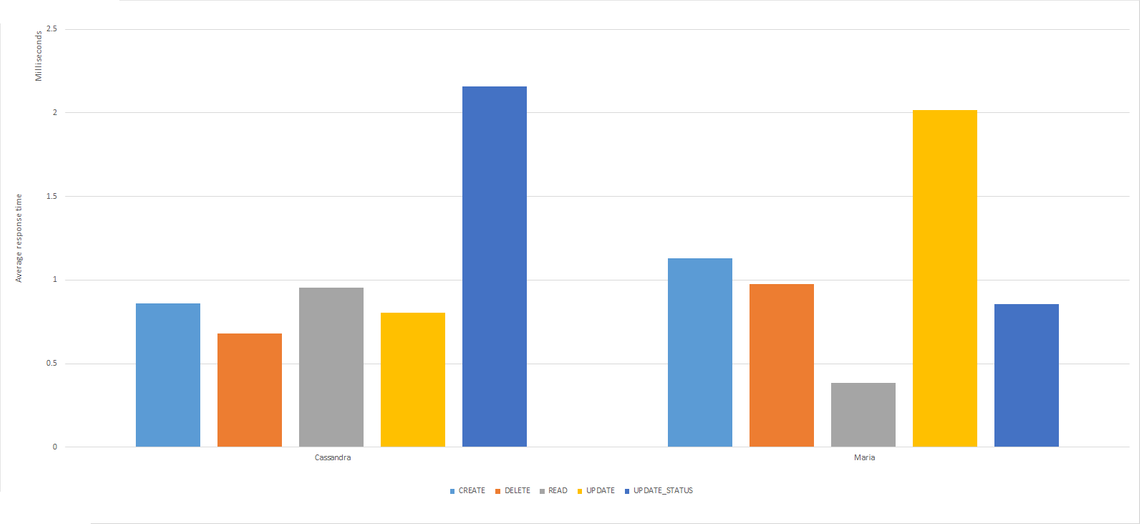

n Random Events

Running 200,000 random events against a relatively small number of orders (500) shows that for ‘create’, ‘delete’ and ‘read’ events both databases are roughly equivalent, managing to return from a query in under a millisecond on average (Fig 4). Reads are on average slightly faster in MariaDB in this configuration but not by much and conversely updates are faster in Cassandra against MariaDB by about the same difference. Updating a single column value however shows a slight difference between Cassandra and MariaDB of on average 2 and a half milliseconds. This may be due to the fact that Cassandra has to access a row to update a column rather than simply write a new row and so it would seem to be more efficient to simply update an entire row with Cassandra. We also found that running these tests with differing sizes of data pre-loaded into the database made very little difference using the simple configuration we set up.

n Update Events

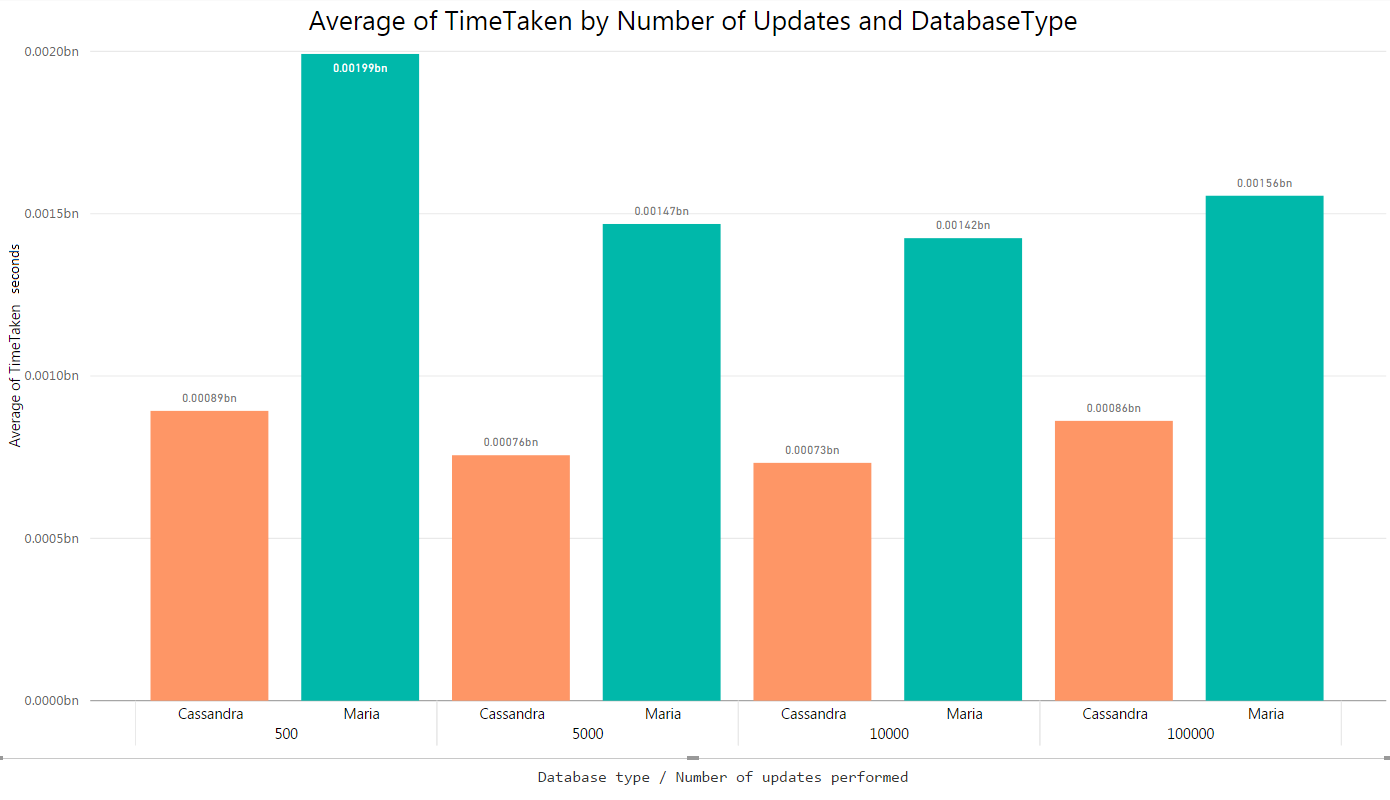

We ran multiple ‘update’ events against both databases in sizes of 500, 5000, 10,000 and 100,000. The results of this showed that whilst the average time taken for an update to succeed remained a relative constant for each database, in MariaDB the time taken to perform updates is roughly double the time taken in Cassandra and there is less consistency. This is perhaps a result of the fact that in Cassandra updates are treated the same as writes to increase performance.

Fig 3

Average Response Times & Overall Execution Times

Fig 4 shows the average response times, by event type, for the same 200,000 events against both of our databases. We made use of the connection pool for MariaDB, setting it to a maximum of 4 connections. As explained under ‘Configuring a Connection Pool for MariaDB’ this should theoretically be the ideal setting to minimise the overall length of execution and to make it a more direct comparison to the Cassandra driver’s executeAsync() function.

These figures should not be considered as rigorous benchmarks, we attempted to bring the MariaDB driver into line with Cassandra driver by making it work asynchronously with the connection pool but neither database has been optimised beyond default settings. Our single-node setup lets us play with the performance features that are under the control of the developer but neither database would be deployed to production in the way we have it set up. That said, it is still interesting to note that as well as having comparable response times to our single-node instance of Cassandra, the overall execution time of MariaDB was just below 55.7 Seconds compared to Cassandra’s 4 minutes and 30.

Fig 4

Conclusion - Hats all folks

Whilst we have gathered interesting results it is worth remembering that we are measuring differences between the two databases in terms of milliseconds. The most dramatic changes we have observed in timings during the course of our investigation have been as a result of configuring how we setup and access the databases rather than differences as a result of volume and velocity of data. Introduction of threading, batch queries, connection pools and remodelling table structures have reduced times by as much as 15 milliseconds on average across both databases. Cassandra handles events as fast, if not faster in some cases, than MariaDB in a simple single node setup without scaling the database out, and using a query language and setup which is similar to, and no more complex than a standard relational setup. This however is dependent on how the database is setup and accessed, knowing the queries that are going to be performed and designing tables around them is of great benefit for performance in Cassandra, as is using the Datastax drivers inbuilt asynchronous execution.

If you know what queries you expect to make on your database, may need your database to scale out and will benefit from a flexible schema then Cassandra would be a good choice. It is very close in comparison to MariaDB In terms of performance and handles row ‘update’ operations particularly well. If your data fits well into a relational model however and you don’t need to scale horizontally then MariaDB provides all the familiarity and benefits of a relational database and performs particularly well for ‘read’ operations as you would expect.