Jest is a testing framework that provides the testing tools we now expect to see in a modern software project. It provides fast parallelised test running, with a familiar assertion syntax, built in code coverage, Snapshots and more. In this post, I’ll be investigating Snapshots and laying out some thoughts!

Why Jest?

Starting a new Javascript project requires you to make some tooling decisions, pick a test runner (perhaps Karma?), pick an assertions library (Mocha? or maybe Jasmine?). Oh, and you’ll want to add code coverage too (Istanbul? Or does Mocha already come with built in code coverage?). Then you’ll need to configure it all.

Let’s be honest, these choices can be a little bit daunting and are just a distraction to your main goal - developing quality software that you have confidence in. On top of that, the less time you invest into configuring your tools, the less reluctant you’ll be to investigate new tooling when appropriate.

The new pattern emerging in software tooling is zero configuration, a la SpringBoot/Create React App, and I couldn’t love the direction more.

Testing React Applications

The general consensus when writing React components is to split them into two categories, smart components & dumb components. Our smart components should be fetching our data, dealing with application state, and wiring together our dumb components. Our dumb components are a pure function of their props returning a virtual DOM representation. They should be responsible for presentation only.

Testing UI code can be time consuming. Asserting the exact DOM structure takes time to write and it can be brittle and thus painful to maintain as the application evolves. The process in general looks something like this:

- Develop the component

- Check the output

- Assert to verify this output

And after making a change:

- Change the component

- Check the output

- Update the test to assert against this new output

What we really want to know is, has anything changed? And if something has changed, is this change expected?

Snapshots

Enter Jest’s Snapshots. The concept is simple and it isn’t a new concept in UI testing. Given a feature, capture the current output and store it. Every time the test runs, assert that the output hasn’t changed. If the output has changed, present a diff and ask whether this change is expected or a test failure.

React already produces an in memory representation of our DOM. Jest simply serialises this representation into a snapshot (.snap) stored alongside the test. This file is then used for future test assertions.

Migrating to Snapshots

I’m going to take Redux’s Todomvc example and convert the tests in their Footer component over to using Jest Snapshots. Here’s the running application.

I’m going to be changing the tests for the Footer component at the bottom of the screen.

Current tests

Here’s an example of one of the current Footer tests.

it('should render container', () => {

const { output } = setup()

expect(output.type).toBe('footer')

expect(output.props.className).toBe('footer')

})

It’s simple enough, render the component with some default props by calling the setup() test helper, which delegates the rendering to react-test-renderer. Make an assertion on the rendered DOM structure.

Now, let’s look at a more complex test that uses the same fundamental approach.

it('should render filters', () => {

const { output } = setup()

const [ , filters ] = output.props.children

expect(filters.type).toBe('ul')

expect(filters.props.className).toBe('filters')

expect(filters.props.children.length).toBe(3)

filters.props.children.forEach(function checkFilter(filter, i) {

expect(filter.type).toBe('li')

const a = filter.props.children

expect(a.props.className).toBe(i === 0 ? 'selected' : '')

expect(a.props.children).toBe({

0: 'All',

1: 'Active',

2: 'Completed'

}[i])

})

})

Both tests are coupled to the UI structure - that’s OK, they have to be. The real burden is maintaining this. Every time your structure changes, you need to come back to a test like this, understand it, get it passing again. Increase the complexity of the tests in question? Increase the complexity of the component? Yep, it’s obvious that this takes effort to maintain. We can mitigate this a little by using libraries like Enzyme for more readable and less brittle DOM navigation.

If we take the second, more complex test, we could do something like this with Enzyme.

it('should render filters', () => {

const { output } = setup()

const filters = ['All', 'Active', 'Completed']

output.find('a').forEach((node, i) => {

expect(node.text()).toBe(filters[i])

})

})

The benefit of this is that we’re not longer so tightly coupled to the structure of our component. All we care about is that there are three <a> tags with the correct names. So we loose coupling, but we loose some of our ability to detect unexpected change. I think we can do better with Jest snapshots.

A change to Snapshots

Let’s change the first test to use snapshots.

it('should render correctly', () => {

const { output } = setup()

expect(output).toMatchSnapshot()

});

Since Jest already ships with Snapshot capability, it’s literally as easy as that. Now when we run npm run test we’ll see Jest create our Snapshots in __snapshots__/Footer.spec.js.snap. (These snapshots should be source controlled along with our tests.) Inside that file we’ll see a serialised representation of our expected output.

exports[`components Footer should render correctly 1`] = `

<footer

className="footer"

>

<span

className="todo-count"

>

<strong>

No

</strong>

...

We can sanity check the serialised DOM should we need to, but we now have our expectation stored alongside our test. Jest has taken away the manual step of writing assertions against the DOM.

Let’s convert the second test from above over to use Snapshots.

it('should render filters', () => {

const { output } = setup()

expect(output).toMatchSnapshot()

})

Once you’ve removed the DOM navigation & assertions, your left with a test identical to our first conversion. This may seem a little confusing at first. How can we take two perfectly valid tests, and replace them with one?

Well, earlier I mentioned that React components are essentially just a function that takes props as input, and returns an in-memory DOM representation. These tests had exactly the same input, so they should have exactly the same output.

Our Snapshots are giving us the ability to capture the entire expected output for a given set of inputs, we don’t have to write multiple tests asserting against specific parts.

We can remove the latter test as it is adding no additional value. Great! One less test to maintain. However, it’s worth keeping in mind that we are losing a little bit of our readable BDD style specification in the process.

Responding to change

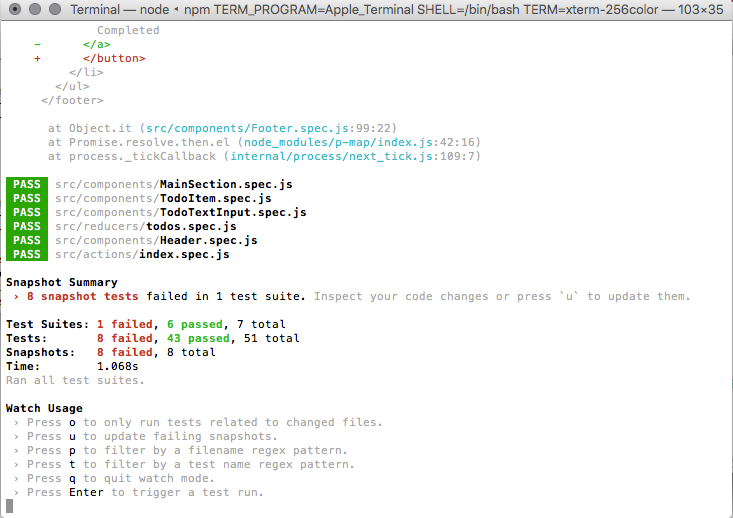

Let’s evolve our Footer component. We’ve now had a requirement to use <button> instead of <a> tags. After I make this simple change. If I run our tests again I get a bunch of failures in our Footer tests.

Jest compares the new rendered output against our saved snapshots, finds a difference and displays a failure. It logs the change to our console as a diff between the old expectation and the new observation.

components › Footer › should render correctly

expect(value).toMatchSnapshot()

Received value does not match stored snapshot 1.

- Snapshot

+ Received

@@ -13,45 +13,45 @@

</span>

<ul

className="filters"

>

<li>

- <a

+ <button

className="selected"

onClick={[Function]}

style={

Object {

"cursor": "pointer",

}

}

>

All

- </a>

+ </button>

...

It’s obvious from the change I made that this diff is expected. So, all I need to do now is tell just via it’s task runner to update the snapshots (as simple as pressing the U key).

Job done.

Why Snapshots are great

Less effort to maintain - Updating our tests were a lot less painful compared to a manual update of all our assertions. This was a simple UI component, but the work is constant even for more complex components with more extensive test suites.

The feedback loop is quick - Jest doesn’t need to render snapshots in the browser, nor does it need to compare images. The result is fast tests that are more reliable, with diffs that are easy to get your head around. We all know the benefits of an efficient development cycle (and the pains of an inefficient one!).

No configuration - Snapshots come packaged with Jest without any extra configuration. There’s no extra effort to set it up, so you can use them where appropriate - with no extra tools to maintain.

What Snapshots don’t do

Not a silver bullet - They give you confidence in your UI rendering, but you can’t rely 100% on mark-up diffs. Especially if you style your components using separate CSS files rather than CSS in Javascript.

They don’t test component logic - Not all component logic is visual. Do you have a UI component that uses callbacks to notify parents of interaction events? You’ll still want to test this!

They don’t replace all DOM coupling in tests - Snapshots reduce how often you’ll need to navigate and interact with your rendered DOM in tests, but not completely. You’ll still want to simulate that user clicking a button! Libraries like Enzyme go a long way to reducing coupling here.

They don’t help with code design/TDD - You could write your Snapshot files up front, manually, but that takes away the advantages. Jest focused on catching unexpected changes. I like to use TDD practices when writing business logic and acceptance tests, but I’m not convinced it’s always a beneficial process when writing UI components.

They don’t keep BDD style contracts - BDD style tests are great, they provide a readable specification for the component. Snapshots tend to result in these readable assertions disappearing. As a result, I think snapshots are best utilized when testing our dumb components. You should also try to keep components relatively small. Picking out a change in business requirements from a diff in a complex UI component isn’t going to be easy.

In Summary

Jest Snapshots take away a lot of the pain I’ve seen when testing the presentational side of components. Any tool we can use that allows us to automate the mundane, and focus on developing features is a win in my book. If you’re already using Jest, there no harm trying them out!

A final word of warning, with test expectations that are so easy to change, it’s important to be sure that the changes are intended. Pressing U on a keyboard is easy to do, but don’t forget that this action is changing the contract of correctness for that UI component. With great convenience, comes great responsibility.

The GitHub project modified alongside this post can be found here.