Last week I attended the CodeMesh conference in London. In their own words:

Code Mesh, the Alternative Programming Conference, focuses on promoting useful non-mainstream technologies to the software industry. The underlying theme is “the right tool for the job”, as opposed to automatically choosing the tool at hand. By bringing together users and inventors of different languages and technologies (new and old), speakers will get the opportunity to inspire, to share experience, and to increase insight.

I also attended last year, where the highlights were Joe Armstrong interviewing Alan Kay (among other things, co-creators of Erlang and Smalltalk respectively); and Joe Armstrong and Sam Aaron’s Distributed Jamming with Sonic Pi and Erlang (why not play a song by scheduling all notes at once?).

As you can imagine I was excited to return this year. There was a selection of talks on topics ranging from rather mathsy, functional-programming oriented, distributed/parallel computing and even philosophical, and on the whole the quality was excellent. The keynote talks however were on another level, so I’ll mention those at greater length here, drawing a couple of themes as I experienced it.

Computer Science history

David Turner gave a keynote on the History of Functional Programming Languages (which I’ll admit to seeing presented before). You could characterise this as “how did Haskell come about?”, and while a little dry (with the distinction of being the only talk I’ve ever seen given in a scrolling A4 pdf format), this was full of interesting details and references to languages I was not familiar with.

Guy Steele’s keynote was in essence an incredible pedantic rant about notation used in Computer Science papers. For me it shows that what seems in essence to be the driest of topics can be most entertaining with a powerful speaker, without any need to avoid technical details (I’ll admit I have exactly the background to have used this notation). Guy has been analysing hundreds (nay, thousands) of papers and categorising their use of notation, and went into detail on such problematic points as the 39 different notations for variable substitution. There was some great history on things like natural deduction, BNF grammars and vectors (see slides).

Doing the impossible

Another theme that spoke to me was achieving the impossible. This started out from the very first keynote, which saw Margo Seltzer describe Automatically Scalable Computation, which is an approach to parallelize computation not by the use of specific languages and compilers, but essentially by predicting the future. Margo described computation as a walk through an immense state space (where a state is basically CPU registers+memory), and pointed out that if we can arrive at a point where we know where the path leads, we can skip ahead to the destination. Essentially the talk consisted of persuading us that this wasn’t just nonsense, sketching out the various components required (such as simplification of the state space based on how instructions actually work, making predictions, executing possible code paths in parallel). And this does actually work - they have a tool which executes an arbitrary binary and learns how to speed it up over repeated runs, speculatively executing predicted portions in parallel, on hardware - with some impressive numbers.

A non-keynote that I’d place in this category was Nada Amin’s Collapsing Towers of Interpreters. This described a layered sequence of interpreters (the notional example was Python -> bytecode -> x86 -> Javascript VM -> ARM) and discussed “collapsing” this into a single compiler. Of course this talk was more abstract and dealt with some particular Lisp variant - but interesting if you’re the kind of person that likes their meta-circular interpreters.

Lastly, the closing keynote was a double-hit, Matt Might with Winning the War on Error: Solving the Halting Problem and Curing Cancer. To quote:

Talk objectives

Solve halting problem. Cure cancer.

The first part of the talk addressed approximating the halting problem, i.e. developing tools to categorise programs as halts / doesn’t halt / don’t know. Matt presented a general approach of finitizing abstract machines to make them amenable to static analysis, and walked us through the consequences of reducing each component to a finite domain (for example reducing numbers right down to -1/0/1, reducing to a finite address space, etc).

The second part took us through Matt’s journey from finding that his son had an unknown rare disease, to becoming (as a qualified computer scientist) the director of a medical institute. This is the story of precision medicine. It’s hard not to over-simplify, so I apologise for my inaccuracy, but essentially this is looking at individual patients’ sequenced genome, identifying mutations that may be linked to a disease, finding possible inhibitors/activators for this (possibly based on modelling), and testing these in the lab. Matt described examples where existing approved drugs which may treat completely unrelated issues appear to be a possible match, and are tested to find a treatment. Matt described his work on a program launched by the Obama administration to work on precision medicine (and there were a few Obama-handshake photos as we went)

The subject matter was powerful enough to start with, and Matt is such an engaging and polished speaker, that this was a really impactful end to the conference.

Wrapping up

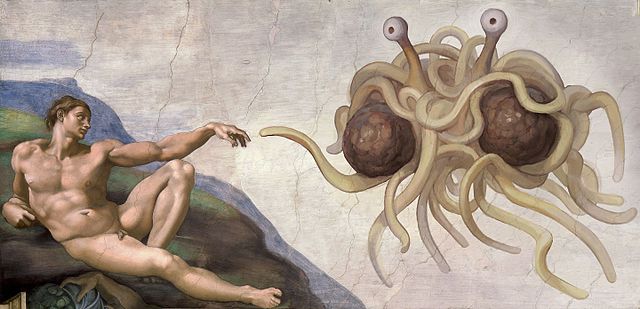

Of course a conference is not just a few headline talks, this was two days of talks plus workshops on top of that. I have plenty food for thought from other speakers, such as 2 talks on the use of finite state machines via indexed monads (blog based on Oscar’s talk here; Flying Spaghetti Monster is worth checking out for the picture alone); a philosophical talk Would Aliens Understand Lambda Calculus; a big hammer and a pony. There are a few talks that I hope to catch later when videos are uploaded - choosing which to attend is hard sometimes.

So is it worth attending a conference like this? Well to me, the value is not in learning specific things, or giving me tools to use in my day to day work (which is not to say that doesn’t happen). I find it reinvigorates me to find software development and computer science interesting and sparks the mind to consider new possibilities. This is a cool field, we can solve interesting problems, and we can develop tools and techniques to do better.