In August 2017 a typosquatting attack was discovered:

@kentcdodds Hi Kent, it looks like this npm package is stealing env variables on install, using your cross-env package as bait: pic.twitter.com/REsRG8Exsx

— Oscar Bolmsten (@o_cee) August 1, 2017

The npm package crossenv was found to contain malicious code that exfiltrated environment variables upon installation.

The attack was executed by the npm user hacktask who authored 40 packages with names similar to common packages.

Examples of package names (and the ones they imitate) in the attack were:

- crossenv (cross-env)

- mongose (mongoose)

- cross-env.js (cross-env)

- node-fabric (fabric)

The attacker tried to use human error and common npm naming conventions to trick users into installing the malicious packages.

A reply to the initial tweet suggested a way to mitigate similar attacks in the future:

would be super useful if @npmjs would deny publishing a package if another one with a #levenshtein distance <3 is already published !!!

— Andrei Neculau (@andreineculau) August 1, 2017

This suggested to create a package name validation based on the Levenshtein distance and reject publication of a new package if the name has a distance of less than 3 to an existing one. This would have identified and blocked the creation of the crossenv package which has a distance of 1 with the name cross-env, and may mitigate most spelling mistakes.

I wanted to investigate whether:

- a Levenshtein distance based validation was a viable solution and see if I could use the npmjs.com infrastructure to find other active typosquatting attacks

- I could use other properties of the attack and package metadata to find other active attacks

Search - Levenshtein distance

The Levenshtein distance is a metric for measuring the similarities of two strings. The distance is an integer which describes the number of single character edits required to transform one string into the other.

We can search the npm repository to find pairings of package names with low Levenshtein distances as these may be cases of typosquatting. If we find low distance combinations of package names and aggregate by author it should be possible to identify authors such as hacktask who have multiple packages with similar names to existing ones.

data

The data required for our search is package name and author, npmjs.com stores package data in a CouchDB database which can be accessed at https://registry.npmjs.com/.

CouchDB is a JSON document store with a REST API for data access/editing. It is built with replication as a first class concept which makes it very easy to make copies of databases.

After installing CouchDB we can locally replicate the npm database with:

# create the database

curl -X PUT http://localhost:5984/registry

# npmjs has two databases, 'fullfatdb' which contains the metadata and attachments and

# 'skimdb' which only contains the metadata, we only need to replicate the 'skimdb' server

curl -d '{"source":"https://skimdb.npmjs.com/registry", "target":"registry"}' \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X POST http://localhost:5984/_replicate

The registry database uses the package name as the key and the value is a JSON document containing information on the package versions.

The data for the package d3fc can be found at http://localhost:5984/registry/d3fc and a reduced representation of the document is:

{

"_id": "d3fc",

"name": "d3fc",

"time": {

"modified": "2017-10-16T16:20:51.718Z",

"created": "2015-06-19T15:46:55.951Z",

"13.1.1": "2017-10-16T16:20:51.718Z"

},

"maintainers": [

{ "name": "chrisprice" },

{ "name": "colineberhardt" }

],

"dist-tags": {

"latest": "13.1.1"

},

"versions": {

"13.1.1": {

"version": "13.1.1",

"description": "A collection of components that make it easy to build interactive charts with D3",

"main": "build/d3fc.js",

"_npmUser": { "name": "colineberhardt" },

"maintainers": [

{ "name": "chrisprice" },

{ "name": "colineberhardt" }

],

"dependencies": {

"d3": "^3.5.4"

}

}

}

}

From this data we want to extract the name of the package d3fc and the authors chrisprice and colineberhardt. Querying data from a CouchDB database requires a View which is written in JavaScript and is similar in concept to a map-reduce query. Views contain a map function and optionally contain a reduce function, these are executed on each document and the results aggregated and returned as a JSON object.

We only need to write a map function to take in the doc as a parameter and call the emit function with the package name and an array of distinct values for the author(s):

function (doc) {

var getNameOrEmailOrNull = function (data) {

if (!data) {

return null;

}

if ("name" in data) {

return data.name;

}

if ("email" in data) {

return data.email;

}

return null;

}

var getSafe = function (p, o) {

return p.reduce(function (xs, x) {

return (xs && xs[x]) ? xs[x] : null

}, o)

}

var namesSet = Object.create(null);

var addToNamesIfExists = function (path) {

var authorOrNull = getSafe(path, doc);

var valueOrNull = getNameOrEmailOrNull(authorOrNull);

if (valueOrNull && (valueOrNull in namesSet === false)) {

namesSet[valueOrNull] = true;

}

};

var searchThroughUsers = function (prefixProps) {

addToNamesIfExists(prefixProps.concat(["_npmUser"]));

addToNamesIfExists(prefixProps.concat(["maintainers", 0]));

addToNamesIfExists(prefixProps.concat(["maintainers", 1]));

addToNamesIfExists(prefixProps.concat(["maintainers", 2]));

addToNamesIfExists(prefixProps.concat(["contributors", 0]));

addToNamesIfExists(prefixProps.concat(["contributors", 1]));

addToNamesIfExists(prefixProps.concat(["contributors", 2]));

}

// doc._npmUser, doc.maintainers[0], doc.contributors[0] etc

searchThroughUsers([]);

// the npm procedure when a malicious package is found is to change the author to npm

// searching for the '0.0.1-security' version of the package finds the original author

searchThroughUsers(["versions", "0.0.1-security"]);

var latest = getSafe(["dist-tags", "latest"], doc);

if (latest) {

searchThroughUsers(["versions", latest]);

}

emit(doc._id, Object.keys(namesSet));

}

After saving the view as getAuthors in the app repoHunt, we can see the results of the view at

http://localhost:5984/registry/_design/repoHunt/_view/getAuthors.

To test the view we can append ?key=%22d3fc%22 which gives us the results of the view run against just the d3fc data and shows the two expected authors:

{

"rows": [

{

"id": "d3fc",

"key": "d3fc",

"value": [

"chrisprice",

"colineberhardt"

]

}

]

}

processing

There are currently over 580,000 package names in the npm repository and applying the algorithm to this many combinations (~1.7E11) presents a challenge. Since we know the set of names to be compared against we can use a Trie and distance upper limit to minimise the search space and then parallelise the computation for each word.

The processing results in a list of name pairings and their Levenshtein distance, we can join this with the authors data and group by author. This should show hacktask and other authors with many packages with similar names to other packages.

The Levenshtein distance between two words can be deceptively small, which may result in a lot of false positive results. To try and reduce noise we can scrape the popular packages from the npm website and join with this data, as attackers are only likely to imitate popular packages.

We can guess the practicality of using a Levenshtein distance based validation on new package names, it will only be practical if new names aren’t rejected a large percentage of the time. We can find the percentage of names with another name of a certain Levenshtein distance to give a rough idea of a new name being rejected.

results

46% of npm package names have another name within a Levenshtein distance of 2 or less (64% for a distance of 3 or less and 26% for 1), this is a high percentage and suggests that the distance name validation may be impractical for new packages unless name choice behaviours change.

We can plot the number of packages and the percentage of names of distance away from another name, against name length:

This graph shows that 100% of names with 1 character are of distance 1 away from a name in npm (logically this is true since the names with two chars include each letter of the alphabet) and that 56% of names with 14 characters are a distance of 3 or less away from another name. The longer the package name, the less likely a package will have a low distance to another name. This is consistent with intuition and supports npm’s recent suggestion to add scopes to package names as part of their new package moniker rules.

The test for this analysis and approach is whether it would catch the hacktask user’s attack. We can aggregate package combinations of distance 1 to popular packages by author name.

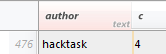

The user hacktask has 4 packages with names close to popular packages and is seen after the 475 users with the same number or more. hacktask doesn’t stand out because of the sheer number of prolific authors in the npm repository (there are 419 users with over a 100 packages and 6 with over 1000). The number of packages, combined with the npm preference for short package names provide a lot of noise to drown out the signal of the low Levenshtein distance.

Searching for low Levenshtein distance pairings has discovered a few authors who are typosquatting but either don’t appear to be doing so with malicious intent or are not engaged in attacks. The authors and packages that look suspicious have been reported to npm.

A disadvantage of the above approach is that aggregating by author name will not catch authors which only have a single, or low numbers of malicious packages. If an attacker wanted to evade this type of analysis they could easily just create an account for every malicious package they published. We can try to look for other traits of the crossenv package for further search inspiration.

Search - package metadata

The similar package name was only one characteristic of the crossenv attack.

There were some other interesting features:

- package used a dependency with a very similar name to it (

cross-env) - package made a call to

nodein one of the script events called on installation. - package versioning does not start at

0.or1..

We can write views to look for all of these characteristics, any packages which fulfil one or more of these criteria might be suspicious.

View - similar named dependency

The crossenv package was essentially a wrapper around the cross-env package that ran malicious code on installation. crossenv needed to have a dependency on the actual cross-env package to function and avoid detection.

We can write a view to find similar packages by running the Levenshtein distance algorithm against a package’s dependencies:

function (doc) {

var getLevDistance = function (a, b) {

if (a.length == 0) return b.length;

if (b.length == 0) return a.length;

var matrix = [];

// increment along the first column of each row

var i;

for (i = 0; i <= b.length; i++) {

matrix[i] = [i];

}

// increment each column in the first row

var j;

for (j = 0; j <= a.length; j++) {

matrix[0][j] = j;

}

// Fill in the rest of the matrix

for (i = 1; i <= b.length; i++) {

for (j = 1; j <= a.length; j++) {

if (b.charAt(i - 1) == a.charAt(j - 1)) {

matrix[i][j] = matrix[i - 1][j - 1];

} else {

matrix[i][j] = Math.min(matrix[i - 1][j - 1] + 1, // substitution

Math.min(matrix[i][j - 1] + 1, // insertion

matrix[i - 1][j] + 1)); // deletion

}

}

}

return matrix[b.length][a.length];

};

var maxDistance = 3;

var latestVersion = doc['dist-tags'] && doc['dist-tags'].latest

latestVersion = latestVersion && doc.versions && doc.versions[latestVersion]

if (!latestVersion) return

if ("dependencies" in latestVersion === false) {

return;

}

var results = [];

var dependencies = latestVersion["dependencies"];

for (var property in dependencies) {

if (property !== doc.name) {

if (dependencies.hasOwnProperty(property)) {

var distance = getLevDistance(doc.name, property);

if (distance <= maxDistance) {

results.push(property);

}

}

}

}

if (results.length > 0) {

emit(doc._id, results);

}

}

View - node script

The malicious code in the crossenv package was executed on the postinstall event. The event executed node package-setup.js, where package-setup.js was the malicious script.

We can create a view to search the scripts node of the latest version of the package and return any calls out to node.

function (doc) {

var latestVersion = doc['dist-tags'] && doc['dist-tags'].latest

latestVersion = latestVersion && doc.versions && doc.versions[latestVersion]

if (!latestVersion) return

if ("scripts" in latestVersion === false) {

return;

}

var scripts = latestVersion["scripts"];

var npmInstallEvents = [ "preinstall", "install", "postinstall",

"prepublish", "prepare", "prepack"]

for (var i in npmInstallEvents) {

var eventName = npmInstallEvents[i];

var script = scripts[eventName];

if (script) {

var scriptContainsNode = script.toLowerCase().indexOf("node ") !== -1

if (scriptContainsNode) {

emit(doc._id, script)

}

}

}

}

View - major version

The first released version of the crossenv package was 5.0.0-beta.0, this is inconsistent with semantic versioning which typically suggests that package versioning initially starts with 0. or 1..

We can write a view to detect if a package is uploaded with the initial package version being greater than 1.:

function (doc) {

if (!String.prototype.startsWith) {

String.prototype.startsWith = function (search, pos) {

return this.substr(!pos || pos < 0 ? 0 : +pos, search.length) === search;

};

}

// detect jumps from nothing to a non 1 major version.

var docTime = doc.time;

for (var name in docTime) {

if (docTime.hasOwnProperty(name)) {

if (name !== "created"

&& name !== "modified"

&& name.indexOf("security") === -1)

{

var firstVersion = name;

if ((firstVersion.startsWith("0.") === false)

&& (firstVersion.startsWith("1.") === false)) {

emit(doc._id, firstVersion);

}

return;

}

}

}

}

results

The package features that these views expose can arise from valid use cases, but when packages adhere to more than one then they become a candidate for inspection.

There are a few packages which meet all of the criteria in the Views but do not appear to be suspicious, an example of these is the package edge-js. This package is a fork of the Edge.js package which explains the initial version number of 6.5.7, has the dependency edge-cs which is a distance of 1 away from it’s name and on install, makes a call to node tools/install.js which appears benign when viewed on Runkit.

Search conclusion

The Levenshtein distance check was not particularly effective due to the nature of the problem and the sheer number of packages in the npm repository. Malicious typosquatting is very hard to detect because behaviour that could be considered as typosquatting is so prevalent.

Examples of this are:

- a package is similar in concept to another package, e.g.

preactandreact. - a package extends a library towards a specific purpose, e.g.

d3fcandd3. - a package bridges two technologies and use the a combination of the words in the new package name, e.g.

bochaandmocha. - someone decides that a package deserves a better name, e.g.

class-namesandclassnames. - a package which parodies another one,

blodashandlodash.

These behaviours aren’t malicious typosquatting, but produce false positives with an analysis based on Levenshtein distance.

The crossenv attack went unnoticed for 2 weeks and isn’t considered to have been very effective due to the low numbers of package downloads. My analysis didn’t uncover any active typosquatting attacks in the npm repository and in this type of investigation, no news is good news. The absence of active attacks leads me to believe that npm must already implement checks similar to those described above and/or attackers don’t consider it to be an effective method. All of the code used in this analysis can be found on github.