In this blog post I hope to talk a little about scaling agile practices upwards (specifically Scaled Agile Framework) and the potential solutions to deal with the big pitfalls involved.

Making agile bigger

One of the most difficult elements of the Agile philosophy is that of scaling. When a single (cross functional) team needs to adopt agile practices, it makes perfect sense to use a system of backlog refinement, estimation, implementation, and retrospective to continually hone and shape the design of a piece of software, test and assess the value the software can add, and (critically) manage expectations of customers / clients on delivery time and work required. The theory is perfect, but all developers will tell you that in practice it can vary widely in its success. Generally, however, the Agile principles work well in software development because they allow teams to be fluid and flexible, adapting to unforeseen problems and more complicated difficulties in the requirements set out by the product owner (PO).

However, as soon as you attempt to scale the agile philosophy upwards to include multiple (dependent) teams, you can end up with a lot of headaches and difficulty in maintaining the fluidity and flexibility that makes agile a useful tool.

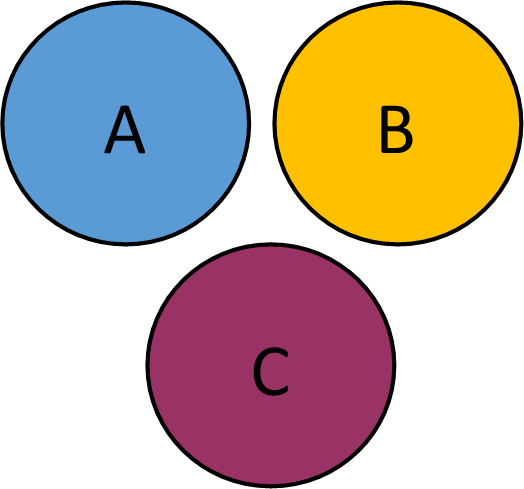

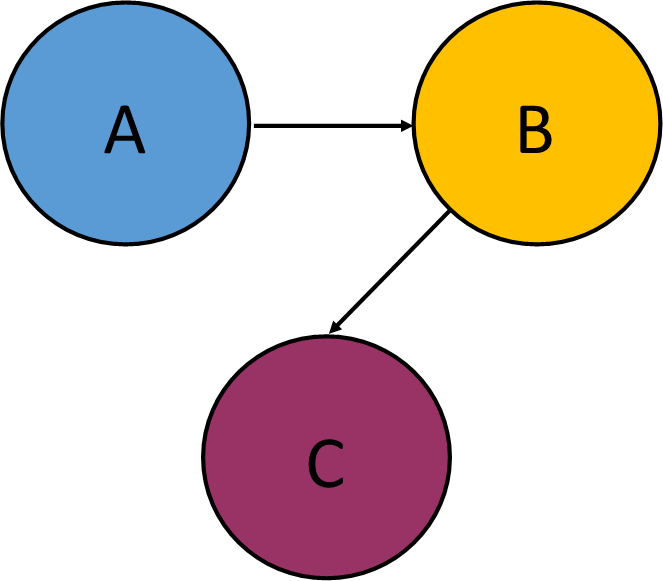

As a demonstration imagine a scenario with 3 teams, team A, B and C, that are all working on different elements of a single large software development. Each of these teams have their own PO that handles backlog refinement. While the elements are different they are not independent of one another and overlap in some crucial areas. Team A has a dependency on team B completing a task in their backlog, and team B in turn has a dependency on team C completing a task. Team C has the item for team B in their backlog.

The Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) approach attempts to take a higher (longer distance) view of the product(s) and timeframes, allowing – in an ideal world – for some flexibility, but with a rough roadmap of the next 8-12 weeks. This bigger chunk of time is known as a product increment (PI) and typically a PI has a large, multi-team planning session at the start. In this PI planning session inter-team dependencies are identified and minimised, allowing the teams to work independently as much as possible. This is usually done via some restructuring of the PI roadmap, and can include:

- Refining the requirements for the PI (Can some requirements be pushed back until a later date? Is the dependency essential or is another technique to achieve the result possible?)

- Prioritisation (How quickly can the dependencies be resolved in the PI so any blockers/issues are made known early?)

- Reallocation of stories and tasks (In our example is team A responsible for a task that should belong to team B or C?)

Each team would only truly do backlog refinement for the next 2-3 weeks, but the rough roadmap of the PI is there as a guide. In theory this can work very well, but is dependent on a few non-trivial assumptions:

- Each development team (A, B and C in our example) are competent with agile practice and capable of successfully estimating their velocity.

- The product owner for each team has a clear view of requirements for the duration of the roadmap. This is not to suggest the PO needs to have every detailed ironed out but understands the general requirements for the next 8-12 weeks’ worth of work.

- (Crucially) Any disruption is easily managed, and the overarching PI requirements are flexible enough to absorb it.

During the PI, blockers can occur, issues can be left to stagnate - this can occur if two teams are responsible for a story and both are under the impression that the other team is working the solution, as an example - and teams can be left unaware of changes to the delivery of their dependencies (which may impact their own velocity and delivery). To mitigate this as best as possible the different teams will each have a representative (typically the scrum master for that team) who will attend regular scrum of scrums sessions to report back on what the team is doing, how the dependencies are being resolved and if there are any team-wide issues or blockers that need resolving. Typically these scrum of scrums occur less granularly than, for example, a daily stand up, but regularly enough that issues can be raised in a timely manner.

The SAFe approach to software development is useful to companies producing or releasing the products exactly because of this longer-term view of the projects. It enables sales and marketing to estimate release dates, finance to consider budget and funding, and it puts the stakeholders / customers at ease to be able to see further into the future than three weeks, even at a coarse level.

What can go wrong?

Two of the difficulties that can be faced when implementing the SAFe approach that should be considered both revolve around the issue of maintaining the flexibility that Agile principles allow, while sticking to the rough roadmap agreed at the start of the PI.

Synchronising teams.

In our example above, A has a dependency on B which has a dependency on C. In the PI planning session at the beginning of the 8-12 weeks, team C estimate that they can deliver B’s dependency by week 4. B plans accordingly to delay that piece of work until week 4 and get on with other parts of their own backlog. Based on the back of this B promises to deliver A’s dependency 1 week later, which A agrees to, as they can continue to work around the dependency for that length of time without being blocked and will have their product deliverable by week 7. This works brilliantly, as the product manager (who has overall responsibility for all teams) would like the last week to be used for refactoring and code tidy-up.

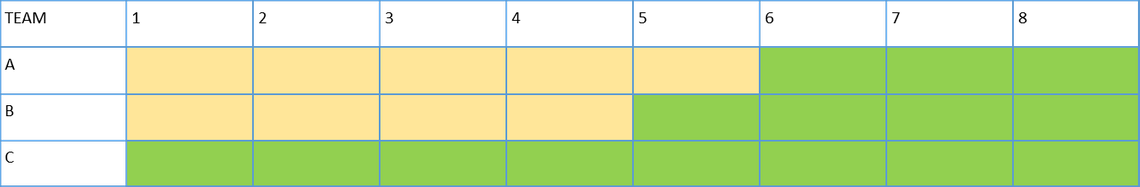

In the following diagram green boxes are a week with no dependencies which the team can work, the yellow boxes are a week when work can be done but that team are waiting on a dependency to be delivered

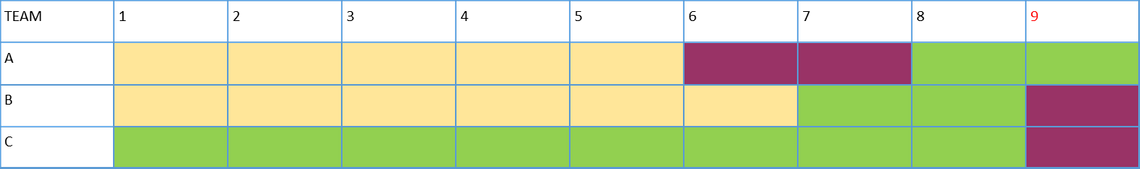

Unfortunately, it becomes clear that team C cannot deliver B’s dependency on time. An underlying issue has been discovered which needs prioritising, and using the agile methodology, the backlog refinement sessions result in the dependency being pushed back by two weeks. Teams A and B only find out about this change three weeks in after the next scrum of scrums, and now the roadmap doesn’t work because A will be blocked from week 5 to week 7, after which two more weeks are required to deliver. Now the project is behind schedule, and a team of developers are blocked.

(Red boxes are boxes where the team cannot work (either blocked or without any tasks to complete)

Allowing time for refactoring and innovation

The project being behind means that now the week the product manager wanted to allow for teams to refactor and tidy code is going to be absorbed catching up with the delay (meaning A and B cannot refactor/tidy their own code despite it being a delay from team C). This is a problem that can (and does) occur all the time in software development, including individual teams using agile methodologies.

How to resolve the problem (are you just using waterfall?)

The solution to resolving this problem is obviously dependent on a lot of external influences: The appetite of stakeholders / the product manager of delaying the release; any external deadlines; the potential for this product itself being a dependency for a different group of developers (SAFe inside SAFe is possible), to name a few. At this point I think there are two options worth considering.

Embrace Agile – when SAFe works well

The reason agile works is seated in it’s flexibility and adaptability. Team C could not anticipate the time sink that existed at the beginning of the road map, and agile practice would suggest adding it to the backlog, prioritising it (in this example, highly) and then implementing, testing, and delivering a solution. Team B can continue working with it’s backlog. Team A being blocked is a tricky problem to solve, but solutions should exist such as mocking the dependency from B. If nothing else is available, then refactoring and code tidy (which the product manager is wanting anyway) can fill the void. This is clearly dependent on the product manager accepting a delay to the delivery of the project.

Accept the project is more Waterfall than Agile – when SAFe doesn’t work well

One could argue that if the product manager and stakeholders cannot accept the agile nature of a delay inside one team then the project is more based on a waterfall approach - and should be treated as such. Rather than adding, testing and delivering a solution team C should be working to implement a solution for team B as soon as possible, and then testing fixing and refining at a later date (as is done with waterfall). Team B should then also adopt the approach, as should team A. Once all the rough edges are done all teams can test and refine their own pieces before one large deliverable is (hopefully) ready by the deadline of the long term roadmap. However, at this point the fluidity and flexibility of agile practices have all but disappeared.

So should we use SAFe or Waterfall?

Any scaled agile approach has issues with dependency management. I am not advocating an “either use SAFe properly or use Waterfall” approach with this blog post. I understand (and agree) that the Waterfall - agile transition is more of a spectrum and a sliding scale then a switch. Indeed the idea of having a PI planning session at the beginning of a longer term 8-12 weeks involving all teams is certainly similar to the planning phase of the Waterfall approach. However I believe agile methodologies are the most optimum way to get the best out of developers and have incremental, meaningful releases of products. If this can be scaled up using the SAFe methodology correctly then that would certainly be the approach I would be attempting to use. But if (for whatever reason) there is a rigidity and inflexibility in the PI planning sessions, such as a hard deadline for regulatory compliance, as an example, then I believe you are better to accept and embrace that the approach is more of a Waterfall approach, and dedicate less time to backlog refinement and estimation, and focus more on delivering the promised product on time.