TensorFlow, as you may have heard, is an open source library for machine learning, originally developed by Google. However, you may not be familiar with TensorFlow.js - an implementation of some of the basic frameworks in JavaScript designed to run in the browser, as well as Node.js, by taking advantage of WebGL to accelerate computations.

Using this relatively new development in machine learning, we attempted to build a web app that applied some of its features. We wanted to recognise products sold in the office honesty store from a camera feed. Along the way we were met with several challenges, however. Hopefully by compiling some of what we learned, it might save you some time should you decide to use TensorFlow.js in future.

What’s it good at?

There’s a few neat examples of what the library is capable of on the TensorFlow.js home page. If you’ve looked at any of these (which can be quite fun) you might notice a common theme in that they all use pre-trained models for predictions or “transfer-learning” when used in the browser, though.

Playing around with the Emoji Scavenger Hunt demo is a great way to see the speedy predictions in action. The app flashes up an emoji and you are tasked with pointing your phone’s camera at a real example of that object as quickly as possible. It’s impressive how well it’s able to pick up on some things and how quickly it identifies objects after they come into frame, despite the relatively low performance of many mobile devices.

That said, it is evident they have compensated for this lack of performance by reducing accuracy and confidence levels. With some Emojis in particular, such as the light-bulb, it is very easy to get a false positive.

The PacMan demo is also a lot of fun to play with. It retrains the commonly used MobileNet network to predict a new set of categories or “classes”. In this instance, those classes are the 4 directions you’d like to move PacMan in. This is an excellent example of how quickly and easily we are able to use transfer learning in the browser to perform basic classifications on, relatively speaking, tiny data sets.

What’s it not so good at?

In the 2 demos discussed above, most of the grunt work is being done by an already trained model. This is a common theme across the other examples and demos. It is clear that the TensorFlow developers have placed a focus on these areas. The reason for doing so became ever more apparent as we attempted to delve into model training for our project.

We wanted a model that could recognise new classes of items from a webcam feed in the browser, much like the PacMan demo. The difference being, we wanted our model to recognise around 50 different products, not just 4 directions. This meant that we needed much more training data. Even only using around 30 images for each class, we would still need around 1500 training images to achieve any kind of reliability in our model. Moreover, other sources suggest a minimum of 100 training images, bringing that total up to 5000 training samples!

But why is this a problem? Well, when running TensorFlow as a dedicated application on your machine, file system access and RAM usage are much more in your control, allowing you to easily manage large training sets. However, in the browser we are not afforded this luxury. Instead, at least in the examples written by the TensorFlow developers, we are simply loading all of our training data into memory immediately and passing the whole lot as one giant tensor to the model for training. Once we started to collect more than a few hundred training images, we started to see problems occurring, most of which manifested themselves as crashes.

Initially we thought that this would be easily avoided by simply training the model on only a small subset of the training data at a time. Then, returning to the model with a new set of data and repeating the process but it turned out to not be so simple. Instead we found that by not providing it with enough examples of each class to begin with, over-fitting was completely unavoidable.

How can we mitigate these problems?

After much trial and error, many hours spent collecting training images, 2 different target devices and hundreds of failed models, these are our top tips for using TensorFlow.js in the browser.

Know your target hardware

TensorFlow.js is obviously targeted at low-power, low-performance mobile devices. Particularly when used in conjunction with MobileNet, for example, a model designed specifically with mobile device performance in mind. However, this does not mean it is capable of running on any old device.

Initially we targeted our project at a low cost android tablet, the Kindle Fire HD 8, but quickly discovered that such devices have limited WebGL capabilities. This is a known issue and might be changing soon but for now these low end devices are missing features required by TensorFlow.js. Therefore, we decided to target an iPad Air 2 instead and found the performance on this device to be much more reasonable.

If considering specific devices to target, it may be worth loading up WebGL Report on a demo model to see what features are supported. Look out for EXT_color_buffer_float in particular as we found this to be a good indicator of whether the device is supported.

Know your target software

When it came to the training process we noticed a distinct difference in success between Windows and Mac OS and even differences between individual browsers. It turns out that Mac’s are much better at in-browser training than PC’s. Mac’s have great support for OpenGL out of the box while Windows does not. Therefore, browsers like Chrome and FireFox use ANGLE to translate OpenGL API calls to Direct3D which is better supported on Windows.

This could explain some of the performance loss. While using our model training app, we were able to load in maybe 400-500 training images in Chrome on windows, a couple hundred more in Firefox and almost none in Edge before the browser crashed. But, on Mac OS, we could easily load up 1000+ training images and while performance wasn’t anywhere near that of the Python TensorFlow library, it did work without crashing the browser.

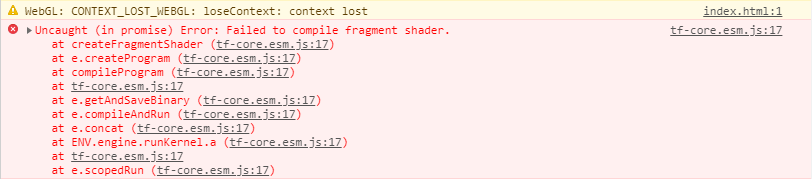

We believe these browser crashes are down to TensorFlow.js having to guess at how much VRAM is available, as this information is not provided by the browser APIs to the JavaScript engine. As a result, it would fill up the VRAM, causing the browser to clean up it’s WebGL instance altogether without any way to catch or prevent it. After which, WebGL would not function at all until the browser was restarted altogether.

It was possible to alter the TensorFlow.js source to fix these crashes by reducing the amount of VRAM it would attempt to use. While this did work, the performance was significantly reduced as a result, so much so that this wasn’t a practical solution to the problem.

Consider training outside the browser

As previously mentioned, we wanted a model that could recognise around 50 different products from a shop - with the possibility to expand on this in future - but we had very little success training such a model in-browser. We were able to train a pretty good model using only 4 products, though. Therefore, if a use case only requires a small number of classes, as with the aforementioned PacMan demo, you can expect to achieve reasonable results. But, anything much higher than this, is probably a no-go. As such it may be that, as in our situation, the models need to be trained using the Python TensorFlow library outside of the browser, exporting this to a web-friendly format for later use using tfjs-converter.

Experiment with confidence metrics

Initially we simply set a threshold value, accepting any predictions with a confidence higher than this value. However, the more classes we added, the less reliable this became. We experimented with comparing the models confidence at its best guess with its second best guess and requiring it be some multiple higher. However, we found that with some products that looked quite similar, this reduced the models performance. Eventually we settled on using a threshold of 80%, with the added condition that the last 3 predictions had the same top result. This worked well in our case as we had a video feed performing continuous predictions.

Use the right base model

In transfer-learning we are using an already trained model and re-purposing it for our own use. This is done by “chopping off” the last few layers of a model and training a new, smaller model to replace these few layers - taking the last layer used from the original model as an “activation” to act as our inputs to the new model.

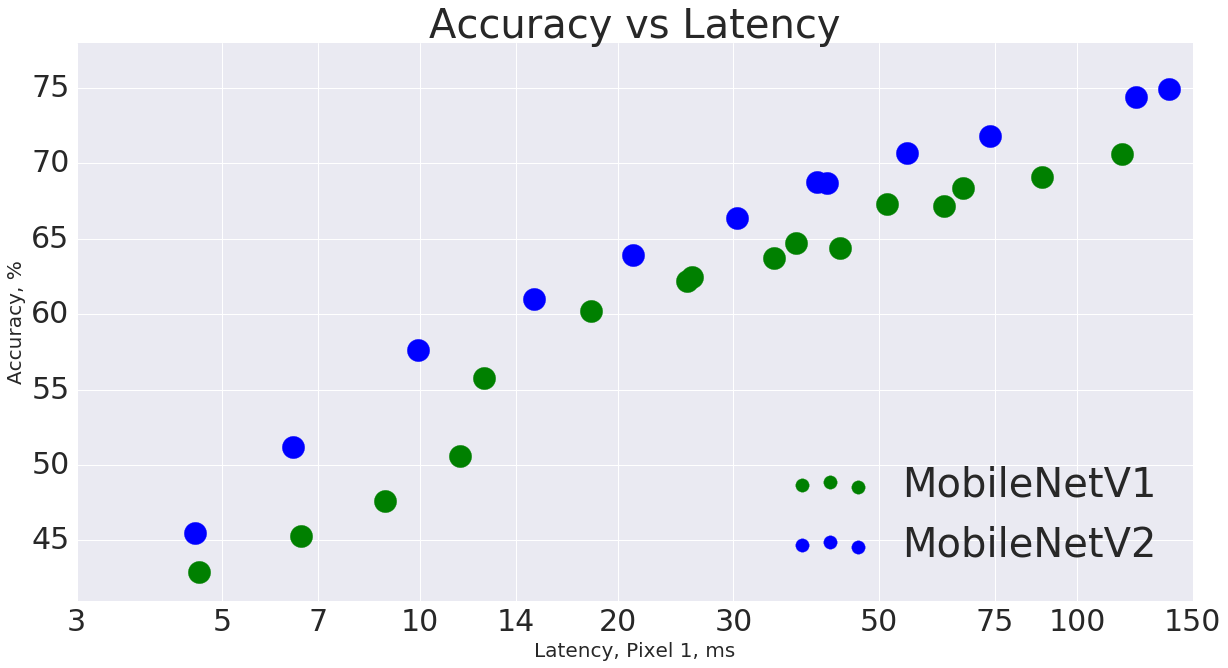

As such, you have a choice of which model to use for generating these activations. The MobileNet collection of models is an excellent place to start for image-retraining on mobile devices but there are several versions listed on TensorFlow Hub. We saw obvious improvements by using MobileNet V2 as opposed to V1 for a start. Additionally, there are different depth multipliers and image resolutions available. The depth multiplier is used to determine the number of nodes used to detect features in the image, a higher multiplier producing better accuracy at the cost of slower performance. Similarly, lower image resolution sped up performance but reduced accuracy.

There’s a handy table comparing the different models on the TensorFlow GitHub that we used to help decide which models to test. After experimenting with a few of these we settled on MobileNet V2 with a depth multiplier of 50% and image resolution of 160 pixels. We found this to be a good compromise between performance and accuracy on the iPad.

Collect good training data

Collecting the training data needed to build a model can be a very tedious process but it is one of the most important factors in training a good model. Our initial training data consisted of myself holding the products in front of a camera in different orientations and angles against a plain but consistent background. The resulting model was quite good at predicting some products, but others it was plain hopeless at. We could only kid ourselves about how good it was by selecting items we knew worked well for so long. So, here’s our checklist for collecting good training data:

-

Collect true-to-life data

By taking images in the same location as what our model would see, we ensured that the background, lighting, and positioning of objects was more true-to-life and we saw vastly better results. Furthermore, as we knew our model would always be seeing images through the iPad’s camera, we collected all the training images using the very same device and camera.

-

Don’t use repetitive data

The more images you have in a class that are too similar to each other, the more likely the model will find something in those images to over-fit to. If 2 images in our training set looked too alike, 1 of them got the axe. This made it much better at picking up on the details we wanted it to, ones related to the object of interest.

Towards the end of our project we had a stream-lined process whereby each member of the team would take a few photos of each product each day. This meant the person holding the product, their clothing, the time of day, lighting conditions, and the way in which a product was held were all varied a great deal across our training data.

-

Make use of an “unknown” class

By introducing an additional “unknown” class it can make it easier to determine if a product is present or not. This class contained lots of random images, such as an empty room or someone standing empty handed, that the model might see that didn’t represent any particular product. This meant that if a product was not held in front of the camera while the model was predicting, the model wasn’t trying its hardest to fit that image into one of the product classes, it simply classed it as unknown. That way we could be more confident in our models predictions when something else came out on top.

In Summary

We found that TensorFlow.js is great for running in-browser predictions and even for re-training models on small datasets. However, should you wish to have a model trained on more than a few classes or with a dataset larger than a few hundred examples, you’re probably best sticking to the regular TensorFlow libraries. Moreover, not all low-end hardware supports the WebGL features needed to perform such tasks and you may have to bring this into consideration.

Lastly, once you start building your models, it’s important to carefully think through how to curate your training data as well as considering the best ways to interact with your model; both in terms of its inputs and how you generate activations, and how you react to its predictions.