This blog post is targeted at people with (at least) a basic knowledge of what source control (aka version control) is. The post doesn’t describe the different tools, or how to operate them, it approaches a subject common to all of them.

When I was reading Software Engineering at university we were taught the importance of software design, the risks with software development and how to manage them. At no point was source control ever covered; I believe this is still the case. The Scott Logic graduate programme covers - from the ground up - the proper use of source control, as it still appears to be a skill that is left for each of us in the industry to ‘figure out on our own’.

I’ve been a developer for many years now, and I’ve learnt to adopt the approaches below. It’s made things considerably easier when developing and supporting the codebases I’ve worked with. Hopefully I can shed some light on why and how it can make the process of software development and maintenance that bit better for everyone involved. I’ll describe functionality and terminology from a git perspective, but I’ve used the same approach to good effect with Subversion and even back as far as sourcesafe.

We’re taught about the single responsibility principle when it comes to software development, why not the same for source control commits. Why is the history of our code any less important than the code itself?

Think about it, you’re asked to implement feature X. It’s a big old change and takes you a week to complete, finally you make one commit so it can be merged. Yes, I know to many of you it’ll seem like an exaggeration, but it happens more than you think. Now if everything with feature X works well then great, fantastic even, I’m happy for you. But think for a moment, if it didn’t go well… what then? I’m not talking about immediately. Sometimes you wouldn’t know until much later.

You’ll either be looking back at the code in a while, thinking “I wish I could undo just that bit” or “why did they do that?”. The thing is you have no idea; it’s clear it is part of feature X but that’s it. You have to keep feature X. It’s essential to your business or it’s required by some regulation. You can’t just revert all of it. So now what? Maybe you’ve worked out what is causing the issue and maybe even why, but you don’t know why that code was introduced.

So now what, you try and find the original author - but they’re on holiday, damn. Next step, take a look at the commit and what else has changed… wow there are a lot of changes there, it’s difficult to see the wood for the trees. Next step, a bit of head scratching trying to find out whether there was a reason for this change. Are there other parts of the system that would break if it was simply undone? This process can take a while to go through and certainly increases the risk of issues cropping up elsewhere.

So what could have been done differently…

If you save each change in its own commit, giving it a clear message§, you’ll build a rich history and increased capability into your codebase. You’ll be able to manage each change in isolation, rather than each change being tied to the others. On top of that you’ll have a rich chronological history of each change made to your codebase with the reasons for them, providing greater insights into analysis in the future.

Software quality doesn’t stop with the code, the history of it matters just as much

Now you can see what changed during the development of feature X, why each change was made and - if the messages are clear - what can be kept or even what needs to be changed to fix your issue. Time, risk and stress reduced 😀

Remember the source control best practices, the most important in my opinion are:

- each commit should contain a single change

- each commit should build on its own (don’t break the build)

- each commit message should support understanding of the changes

If you remember to commit early and often it will help approach the above, and save confusion and hassle when you come to the end of the task. Also, with git, don’t be afraid to rebase (rewrite history) - so long as you follow the rules!

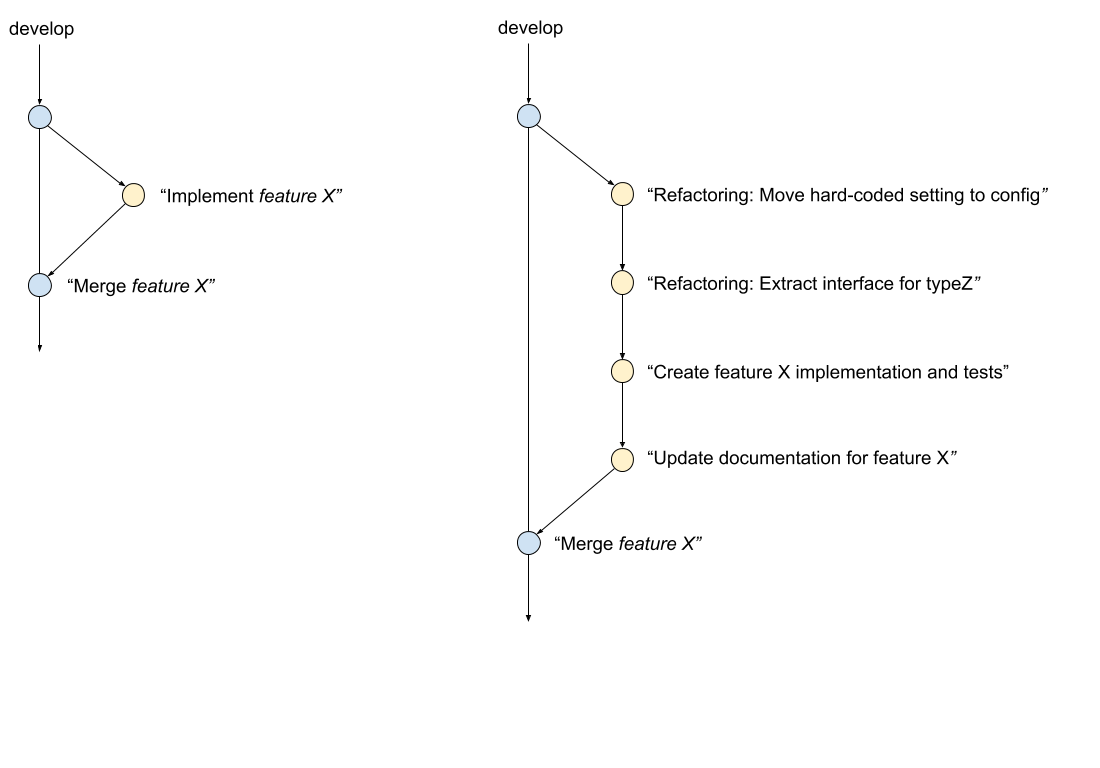

Compare the following:

Each refactoring commit has a value, and the message§ is part of that value. It explains why the change has been made. Anyone code-reviewing feature X, or assessing the history of those changes in the future can see the reasons for them. If you want to revert (for example) the config setting you can. You don’t have to - manually - reverse engineer the change.

Understanding how and why a codebase has evolved supports the effective development and maintenance of it in the future.

§ It can be a good idea to include story references in your commit messages, e.g.

ABC-123- Refactoring: Extract interface for typeZ

The message format will vary between projects, but the practise adds some additional value to each commit. You don’t need to assess when it’s been merged; you can see all of the changes related to one task (and its additional detail) in the commit history.