Microservices is no longer new and shiny. Maybe it never was - it being a term coined in the early 2010s to describe an emerging set of common architectural characteristics, a kind of “lightweight” Service Oriented Architecture. Many organisations, following the lead of pioneers such as Netflix or independently, were doing it long before it had a name.

A few years down the line, with the explosive growth of cloud computing and the convergence on enabling technologies such as Kubernetes - and in particular the availability of such platforms as managed services in the cloud - the barrier to entry to this architectural style has lowered dramatically, contributing to its increasing popularity.

Now that microservices is a thing, with so many organisations claiming to do it or aspiring to, it’s time to re-examine: What is it really? What advantages do we hope to gain and at what cost? Under what conditions is it right? Is it still the future?

This post is about my own opinions, formed from my own experience. I am fortunate to have witnessed the evolution of a system and engineering team on a more than 10 year journey, before, through and after taking the microservices approach.

In my view microservices is not an architectural blueprint for the perfectly optimised system. It’s not about REST APIs or containers. Rather it is a loose set of principles, aimed at supporting and arguably depending upon a certain software engineering culture. Its benefits pay off in the long term, for systems that must be continuously adapted while they run, to exploit emerging opportunities and respond to the unexpected challenges of business.

Microservices is therefore more about people and change than about any specific technology.

What defines the microservices approach?

From the technical architecture point of view, I would summarise the microservices approach with the following set of principles:

- The system is decomposed into small services

- Decomposition is by functional area rather than technical concern

- Services are independently deployable

- Services communicate using simple mechanisms and formats

- Services manage their own data

- Service coordination is done by the services themselves

Small services

Small is of course a relative thing. In terms of code, in my experience some might be simple enough to have only 10s of lines of meaningful logic, but generally 100s or 1000s and probably not 100s of thousands. That said, lines of code is an imperfect measure of complexity. Every case is different, and it depends on the language and style of implementation as well as what the code is actually doing. The important point of course is separation of concerns: break a large multi-faceted system into smaller parts.

Decomposition by functional area

The separation of concerns into microservices is unlike traditional n-tier architecture where decomposition is based on layers of technical abstraction - validation tier, business tier, data access tier for example - although internally, each service may indeed be structured along those lines. What functional area really means is highly dependent on context. It could be business domains, or groups of closely related features.

Independently deployable

Independently deployable means that each service runs in separate processes, often on separate host machines although not necessarily so. This means they can be stopped, updated and started independently, but of course does not necessarily mean they have no dependencies on other services to get their actual work done.

Simple mechanisms and formats

Microservices are so often associated with REST APIs that one would be forgiven for believing these things are synonymous. Simple HTTP request and response mechanisms with JSON bodies, such as in the RESTful approach, are a popular choice, owing in part to their accessibility to browser technology. The main point though is to prefer mechanisms that are ubiquitous or simple enough to implement that they don’t tie to a specific platform or runtime. This is in contrast with platform-specific remote procedure mechanisms such as Java RMI or .NET Remoting. Even “Web Services” standardisation attempts such as SOAP suffered ultimately from diverging implementations causing compatibility issues.

REST is a fine choice for many scenarios, but there are many cases where other communication mechanisms are a better fit for requirements. In my experience REST is commonly mixed with one or more asynchronous messaging mechanisms - for example queues, publish/subscribe. Event-driven and streaming approaches are increasingly popular and worthy of discussion beyond the scope of this post. The main principle remains: keep the means of communication as simple as possible for the sake of broad compatibility.

Services manage their own data

Let’s make the assumption that in our system the storage of some kind of data is inevitable. Given that we decompose the system by business domain area, this means broadly speaking each service is responsible for dealing with distinct parts of the overall data. Sharing data stores between services should be avoided to reduce coupling, so that each service’s data schema may evolve independently.

It has become very common to use a variety of storage mechanisms across an overall system to best meet the functional and nonfunctional requirements of its features - for example a mix of relational databases, key/value stores such as DynamoDb, and search indexes such as ElasticSearch. This idea is sometimes referred to as polyglot persistence. The use of more than one type of storage is not of course a prerequisite of microservices, but the decomposition supports making that choice independently in each part of the system, as well as retaining loose coupling.

Service coordination is done by the services themselves

By definition one system cannot be decomposed into separate parts that have literally no dependencies on each other. The parts must work together to perform a useful function. In microservices this means features generally involve multiple services. We’ve discussed the mechanisms of communication above, but what of the coordination, or flow, of work across the system?

The microservices approach advocates that it is the services themselves that perform such coordination, as opposed to the alternative that this is centralised into some kind of service orchestration platform. The idea, dubbed “smart endpoints, dumb pipes”, is that all business logic, even high-level workflow, belongs in the implementation of services, not in the mechanisms that provide the infrastructure for communication. This is one way in which the microservices approach distinguishes itself from Service Oriented Architecture, where often some kind of configurable middleware system such as an Enterprise Service Bus provides capabilities like data transformation and routing of client requests to appropriate services. In practice this means finding new ways to solve the issues that such platforms attempt to abstract out, such as for example the handling of exceptions, or the monitoring of communication between services. The core idea, just like services managing their own data, is decentralisation.

For a more thorough description of the microservices style and its origins as perceived back in 2014, I recommend Martin Fowler’s microservices paper.

What’s in it for me?

Adopting a microservices approach can bring significant challenges. It is certainly not what Extreme Programers would call “the simplest possible thing”, and so with a healthy scepticism and a lean enterprise mentality, why would we choose to go there?

The guiding technical principles described above are all intended to protect freedom:

- Freedom of teams to focus on smaller parts of the business domain

- Freedom of teams to test and release different parts of the system independently

- Freedom to adapt to new business opportunities or challenges over the system’s lifetime with reduced risk to other parts of the system

- Freedom to scale different parts of the system independently

- Freedom of teams to choose the right technology and tools for each part of the system independently

- Freedom to evolve technology choices incrementally over the system’s lifetime with reduced risk through experimentation

The value of microservices depends on the value you would ascribe to these freedoms in your particular context.

None of these claimed advantages is new or original, but the last of these seems often overlooked, or at least underestimated. Without the benefit of hindsight it is difficult to anticipate the value in this long-term benefit of evolution through experiementation. It is also extremely hard to achieve it without similar principles of decentralisation.

The last big rewrite

In 2006 I joined a startup providing a platform for music download and streaming services. Through multiple acquisitions over more than 10 years, the organisation served many masters and was subject to huge and unpredictable changes in direction. Meanwhile its system grew to cater for many different consumer-facing incarnations and gained millions of consumers worldwide.

In the beginning was the “monolith”, typical of its time, a fairly complex multi-tier web app backed by large relational databases.

In 2008, the decision was taken to rebuild from scratch due to a build up of seemingly intractable problems:

- Huge cost of scaling up to meet user demand

- Pressure from the business to build new features very quickly to meet new requirements but in the face of already crippling complexity

- Pressure from operations teams to NOT change the system due to the risk of downtime involved in the complex manual release process

- User experience improvements difficult to achieve with existing architecture and yet too dependant on existing logic and data to make use of alternatives (example: universal search)

With the benefit of knowledge of the domain and the existing technical challenges, we chose to break the new system down into loosely coupled services, following our own loose interpretation of Service Oriented Architecture. We defined the interfaces between the services as REST(ish) APIs and ignored what we considered the “enterprisey” elements of SOA, in particular Enterprise Service Bus, in favour of simple direct communication between services. Importantly, for the sake of splitting the work into multiple teams, we avoided as much as possible the idea of shared infrastructure services - another common SOA idea at the time. Our services each ran on their own sets of virtual machines, therefore independently deployable. Essentially we started down the path of microservices, like many others, before the term was coined, and before many of the enabling technologies such as Docker and Kubernetes had emerged.

It’s worth reflecting on the fact that we did not try to take the monolith and evolve it into microservices (the “monolith first” approach). What we already had was much too tightly coupled and riddled with legacy complexity. Rather we took this very rare opportunity to start from scratch. This was an expensive and painstakingly managed migration, running two entire systems side by side for many months while clients were gradually migrated or deprecated. It was however the last big rewrite. Not because we arrived at the ultimate solution, but because the new approach gave us freedom to change.

Here are some of the very many changes that happened in the years that followed:

- The new system grew from around a dozen microservices initially to over 50, created and maintained by multiple independent teams.

- While adding a new microservice was relatively common, some were also deprecated as older features became redundant. By monitoring requests it was easy to remove unwanted legacy parts of the system.

- Given the skills of the existing teams, initially most services were .NET / Windows with just a couple of services deliberately Java / Linux to allow easier interoperation with open source tech including Apache Solr for search. Gradually Windows-based services were replaced with open source-based services reducing the licensing cost.

- As new services emerged we tended to prefer JSON for message format rather than XML, and so the latter was gradually phased out. Some services supported both for a period of time, usually with a thin “transformation layer” for backward compatibility that was later removed.

- Some engineers experimented with functional programming languages Scala and Clojure. Due to the relative simplicity and clear APIs of each microservice it was possible to incorporate this into real work with low risk, either by using it for a new service, or by rewriting an existing service, without affecting other services.

- By 2013, Clojure had gained traction in the engineering community and eventually became the preferred language for all back-end services. (Clojure is awesome, but that’s another epic!)

- There were similar stories with databases: services owned their own data, so teams were able to introduce new storage and query approaches. For example MongoDb, MySql, ElasticSearch and various “no sql” stores including DynamoDb. Some of these were adopted broadly and others were eventually phased out based not only on their features but on ease of use and operability in production.

- Increasing focus on collection and use of consumption data to drive business analytics and personalisation features led us to introduce a pub/sub architecture for event data using Apache Kafka. As microservices began to produce and consume events, the architecture evolved to a mixture of event-driven and request/response interactions.

- Initially hosting in traditional data centres, gradually new parts of the system were created in Azure and AWS using a hybrid approach until eventually everything was migrated to the cloud.

By 2016 the system was almost unrecognisable in terms of features, architecture and technology stack, compared to that of 2009. Despite increasing demands of scale and high availability, and ever more varied and challenging feature requirements, change was achieved in small, relatively low risk, evolutionary increments.

Of course this cannot all be attributed to software architecture alone. Intertwined in this story were other related organisational and cultural transformations, absorbing ideas from industry trends of the time, most notably:

- Adoption and evolution of agile ways for working - most importantly the embedding of a culture of incremental and continuous improvement, rather than any specific ceremony or process.

- Removing the organisational boundaries and conflicts of interest between developing, testing, releasing and operating software in production, i.e. what has become known as DevOps.

Agile, DevOps and microservices were all complementary aspects of this journey towards a culture of autonomy. The pace of change achieved would certainly not have been possible without the freedoms afforded by microservices approach.

With freedom comes responsibility

To adopt a microservices approach we must accept the challenges that come with it. Some of the potential technical pitfalls are easily predicted - for example increased latency due to additional network hops. I’d like to focus here on some of the less obvious aspects - what it takes to embrace autonomy, the responsibilities this brings and how this both depends upon and ultimately benefits engineering culture.

The art of decomposition

Separation of concerns is the art involved in microservices. There are no prescriptive rules about where the service boundaries should lie, whether a feature should be implemented in one service, or yet another new one. There are no strict limits on how coarse or fine grained to make the services. Since decomposition is by business domain rather than technical aspect, this is all context dependent.

The point of this of course is to align software delivery teams more closely to the different parts of the business, or features of the product offering, so that each may independently focus and create value more quickly. This means the decomposition into services is somehow related to the structuring of the teams along functional lines. Often this means teams end up owning one or several closely related services.

The APIs of the services in the general sense are the boundaries of decomposition. The importance of time spent on API design discussion cannot be underestimated, especially when attempting to spread the work across multiple teams. This should be a cross-team collaboration thing, whether led by team members or people with broader oversight such as architects. Even if internal only, the API is a contract to others and therefore should be simple, understandable and useful. This applies not only for REST-like APIs, but anything that forms the interface between services - e.g. event message formats and so on. It is the APIs themselves that should be expected to stand the test of time above all other implementation details.

Even when there is only one team initially, the division of the problem space into small loosely coupled parts is central to the microservices approach and worthy of careful consideration before diving into implementation, in anticipation of future growth and evolution.

Let’s say we’re starting from nothing - a “green field” project. What of the commonly touted advice to “start with a monolith”? With an extremely disciplined internal design structure, one could imagine delaying the decomposition into separately deployable pieces, but in my experience this is rare. It is far easier to combine separate services into one (for the sake of performance gains for example) than it is to separate an already tightly coupled system for the sake of freedom. If you buy into the microservices benefits, then with an awareness of the culture it requires as discussed in this post, my advice is to set out as you mean to continue: with fine-grained microservices from the start. To quote Stefan Tilkov, “I’m firmly convinced that starting with a monolith is usually exactly the wrong thing to do.”

What if we get the separation wrong? Just a few example signs that decomposition is causing problems could be:

- Dependencies on other teams paralyse productivity

- Temptation to reproduce features that exist elsewhere to remove dependencies

- Use cases involve many services (“hops”) degrading performance to an unacceptable degree

- The same data appears in multiple systems causing potential inconsistencies or complex coupling for synchronisation

- Fear of changes due to risk of breakage to other systems

- Services become so large that their own build and test processes are cumbersome and slow

- Many people (or even teams) work simultaneously on the same service tending to “step on each other’s toes”

Some of these are a matter of granularity: too fine perhaps leading to wasted effort and poor performance for limited benefit in terms of flexibility; too coarse leading to lack of independence. Others are related to the division of the problem space across teams and dependencies between them.

At the technical level there are of course techniques to be aware of to better reduce the risk of issues due to dependencies. APIs must change over time of course to accommodate new features, and ideally to remove features as they become redundant. Simple principles like “tolerant reader” can help with this. Changes such as adding new resources to REST API should always be safe, but sometimes the most common changes such as adding new data fields to responses can break clients if they are not created with tolerance in mind. To put it simply, a client should only use what it needs and ignore anything else.

One mitigation I propose for dependency problems between teams is weak service ownership, meaning that teams are capable and supported in making changes to other team’s services when necessary. To compare to Martin Fowler’s code ownership description I would advocate collective code ownership within a team and weak code ownership across teams. It may be tempting to believe that in a scaled agile software organisation running with a pure feature teams approach, there should be no sense of teams owning services: each would be tasked with implementation of new features and expected to change whatever part of the system that requires. One could call this collective service ownership perhaps, i.e. collective code ownership across all teams and services. However, I would be wary of deliberately denying the sense of team ownership and treating teams as completely fungible. With the microservices approach, business domain areas, and therefore features, should align largely with service boundaries. Therefore in reality feature teams working with microservices tend to focus their attention on some services more than others, in a way that lends itself naturally to gathering domain knowledge. I believe there is huge value in teams building domain expertise and feeling guardianship of their software products - more on this later. What I would advocate is more like the “empowered product teams” as described by Marty Cogan. Of course we are bleeding into a much broader topic of product ownership here. Anyway, weak service ownership accepts and supports the idea of domain expertise within teams while providing means for teams to unblock themselves.

We need to accept that an initial attempt at separation of concerns, both at the detail and at the business level, will be imperfect and will need to be corrected. Of course this will also continue to be true over time as the business adapts to new challenges. Therefore to remain productive and support the changing needs of the business, there must be an acceptance of and support for change of engineering team structure over time. If we are to expect the software to continuously adapt to reflect the business need, then so too the team structure.

Autonomy through trust

To follow the microservices approach requires each of these business-focused teams to possess a broad range of skills. This may involve individual collaborating specialists within the teams, or generalists taking on the breadth of knowledge to fulfil multiple roles as needed. Either way, the technical skills to write application code is no longer enough now that the team must not only develop but also design, build, test and deal with a wider range of technical pieces such as databases and infrastructure.

Further, to achieve real autonomy and independently deliver value to the business, each team must be empowered and trusted to deploy and run its software in production. This is of course what has become known as DevOps. Whether each team is responsible for the whole operational function, or works in close collaboration with a specialist operations team, the point is that delivery teams must be trusted to change things.

To get to this point can be a painful journey. Referring back to my music streaming story, DevOps was a vital part of what became a highly productive engineering culture, but it certainly did not start out that way. There were the typical boundaries, checks and processes in place to try to reduce risk of downtime, people employed to apply these controls, and operations teams whose incentives were based on uptime, not the delivery of new features. In short: conflict. It turned out the key in our case was to slowly reduce the conflict by ensuring that all teams had largely aligned business targets: in this case, customer engagement, not basic measures of availability. This did not mean all the checks and balances went away, but that the product delivery and operational teams started to collaborate positively to deliver value, and to find ways to do this more efficiently. This collaboration, taking small steps, eventually fostered the required trust for autonomy. There is risk in any change, but microservices principles helped to make the changes smaller. Frequent, tiny changes are far safer than large complex changes made infrequently. Over the years that followed the big rewrite, this meant gradually shifting from four complex major releases per year to a constant flow of many small independent releases every day.

A related issue of trust exists within the product delivery organisation: engineers must be trusted to decide how much effort is devoted to essential non-functional aspects such as monitoring, logging, automated testing, delivery pipelines and so on. The priority calls involved here become much easier to deal with as a collaborating cross-functional autonomous team with empowerment and ownership of their own area. It’s not something that appeals to every developer maybe, but in my experience engineers who have direct visibility of how their software behaves in production tend to enjoy this and feel compelled to nurture and improve it. Not only to add features and fix bugs, but also to improve visibility, stability and operability.

Given the right support, this sense of ownership engenders a bottom up rather than top down approach to quality.

Developer anarchy

The microservices approach gives us freedom to “choose the right tools for the job” for each part of the system independently. That’s a clear benefit. In practice, how far should we take this?

Do we allow uncontrolled divergence as each team makes their own decisions? Different frameworks, programming languages, runtimes? Different cloud providers? All of this can certainly be made to work, given enough autonomy and loose coupling. I know organisations that have allowed divergence to go this far, but at what cost?

With microservices it remains as true as ever that sharing common tools and approaches across an organisation has its advantages. For example, wherever some aspect of operations remains centralised, it makes sense to consolidate as much as possible cross-cutting concerns such as monitoring, logging and tracing. Not to mention the obvious fact that it’s more manageable to host things in the same data centres! So there are bound to be cross-team decisions, likely involving people with broad technical oversight.

There’s also the notion that a “stable stack” is necessary to ensure developer productivity. Language and runtime in particular is very commonly deliberately fixed. One often hears an organisation describing itself as a “Java shop” or “.NET shop” for example. There are many sane reasons for this, over and above someone’s personal preference: to avoid the burden of cross-training when moving between teams, to maximise re-use of shared libraries, to focus hiring, and simply to build deeper technical expertise by sticking to one ecosystem. In the extreme case, autonomy threatens to erode all of this.

Stability and consistency are sensible motives. However, with the best intentions and preparation, technology choices taken, just like business ones, often turn out to be wrong. They certainly rarely remain optimal for long periods of time.

Technology itself moves on. What was state of the art eventually becomes old hat. The consequences of falling behind the curve are compounding: most obviously, we miss out on the benefits of technical advances, but perhaps more importantly, it becomes demotivating for the engineers involved. This leads at best to reduced productivity, at worst to attrition. People move on too: they want to try new things and seek to exploit new advantages. The best technologists thrive on continual learning and improving. They have their careers to consider too.

So there is a careful balance to be made between stability and evolution - somewhere between constraint and chaos.

Experiment to evolve

One of the great things about a microservices architecture is that technology changes can be made independently to small parts. There is no longer the need for an expensive and risky “big rewrite” to replace everything. Rather try something new in a small part of the system and roll it out incrementally if successful. This allows for experimentation, which I believe is fundamental to long-term motivation and productivity.

It’s worth a quick diversion to clarify what I mean by experimentation. Of course, given a little spare time, anyone can experiment with technology with zero risk to the business. However, there’s nothing like working on real world business problems, operating live services, and collaborating with others to really prove out an approach. So I include the notion of experimenting in production, i.e. doing it as part of day-to-day work, which is why the decentralisation of the microservices approach is relevant for the reduction of risk.

In my experience many of the most successful and enduring technology changes have come about through the experimentation and advocacy of software engineers, rather than at the instigation of senior technology leadership. The adoption of the utterly awesome Clojure is just one of many examples of this from my music streaming story. This does not mean developer anarchy, or a lack of oversight. Evolution of the “stack” happened organically, with the support of and in collaboration with leadership and those with broad responsibility such as architects, operations teams and business owners.

This requires leadership to embrace the passions of the engineers. Give them the time to experiment. Trust them to take controlled risks and challenge them to measure outcomes. Allow them the freedom to fail and ensure that they have the support structures to communicate, promote ideas and collaborate across teams. This helps to create a culture of self-organised consensus - neither top-down governance, nor unchecked divergence.

Let’s not forget the most important point here: experimentation is fun! Fun is motivating, and motivation, along with ownership and trust, leads to high productivity and innovation.

Unconstrained complexity

With more independent parts to manage, the microservices approach does not necessarily make a system simpler as a whole. If we are doing it properly each of the services should be simple in itself, but the complexity of the system overall moves into the interactions between these services to perform their functions.

To achieve a highly available service supporting continuous deployment, a microservices architecture tends to also require more complex hosting infrastructure, tooling and processes to manage than a more “monolithic” equivalent. These non-functional aspects of the solution should be less frequently changing once in a stable state than the functional microservices themselves, but the setup can be a significant investment. Happily in this area, the industry has made huge progress over the last few years - a prime example being Kubernetes, which has become a de-facto standard for hosting containerised microservices. Now that Kubernetes is offered as a managed service by each of the major cloud providers following Google’s lead, the growing pains and operational overheads previously associated with configuring and running such platforms are dramatically reduced.

Testing can also be more complex to achieve in a microservices environment due to the out-of-process dependencies involved. Confident, independent continuous deployment requires strong automated testing at multiple levels of abstraction. Automated testing for microservices is a topic I wrote about a few years ago in a previous role.

It is likely and natural that a microservices architecture, as any other system responding to changing context, will become more complex over time. How do we tame that growing complexity? How do we ensure appropriate knowledge is retained to allow people to continue to work within it?

On the issue of knowledge, my general advice would be: favour observation of system behaviour over written documentation. It will be even more difficult in the case of multiple autonomous teams to continue to accurately document the entire system. In the sentiment of the agile manifesto “working software over comprehensive documentation”, it’s better to let the latest code and the automated tests be the source of truth on the working details of each microservice. But what about the overall system?

Architecture diagrams are extremely useful to convey understanding of processes and dependencies, but as the system grows, it’s unlikely that it will all fit into one clear picture. Further, without incredible discipline and cross-team coordination, manually crafted diagrams, just like detailed documentation, will never keep up with reality. Ultimately we must let go of the objective of creating accurate and complete architecture documentation.

Rather than rely on incomplete and potentially inaccurate clues about how services depend on each other, we can also use tools and techniques to observe system behaviour in production. Modern monitoring and logging techniques allow us to diagnose operational issues. Given appropriate access and tools, data such as request logs can also help developers to explore how the system is working, although it is often difficult to piece together the data from the distributed system in a way that helps explain end-to-end features. An extension of this idea called distributed tracing can provide the means to link log messages together and using this data interactively explore and visualise how interactions flow through the microservices system. Compared to gleaning dependencies from source code and configuration, this has the added advantage of reflecting what’s actually used in the production system and can be used to identify performance bottlenecks and opportunities for optimisation at the level of service interactions.

As a business expands, it’s going to be rare that we can reduce necessary complexity over time. However, as demands evolve there may be features or even whole business areas that become redundant. In a microservices architecture, more so than most other approaches, it’s easy to remove the unwanted legacy. Even when it’s not obvious what is actually redundant, using monitoring and logging, it’s possible to detect when certain API resources or entire services are no longer receiving requests and may therefore be removed completely.

Is growing overall complexity bad or just necessary for business?

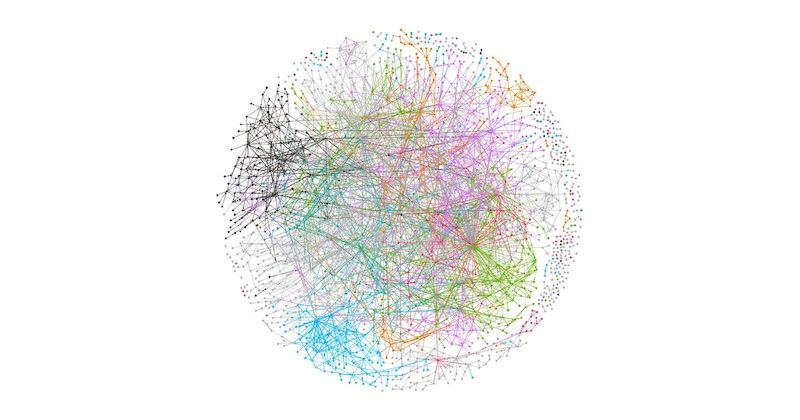

Monzo bank is an interesting extreme case, its story attracting attention in software circles due to the sheer number of microservices involved. According to their 2016 blog post Building a Modern Back End, they had 150 services at that time. That’s similar to my experience. More recent tweets and blogs appear to argue about the sanity of Monzo growing their platform beyond 1500 microservices. It’s likely that the complexity of the overall solution in terms of what it achieves functionally is no more than in almost any other bank. What’s different here is that they can visualise some of that complexity as a network of interacting microservices. It’s clear there must be interesting challenges there, but the fact they continue with the strategy shows it seems to work for them. A more monolithic approach often has numerous dependencies and couplings that are hidden and require deep code analysis to discover and understand, whereas by externalising these as relationships between microservices, the couplings are surfaced and visible.

Maybe complexity overall doesn’t need to be constrained: to do so might constrain the business itself. Rather we must learn to cope with it, observe it, navigate it and communicate about it. Understanding, just like responsibility, becomes devolved.

Are microservices right for me?

To wrap up, in summary my advice is this:

For anything roughly matching the following description, I would strongly recommend considering a microservices approach:

- Building a scalable bespoke system with a non-trivial back end

- Large enough to have multiple functional areas, potentially multiple software teams

- Long intended life expectancy (years)

- Likely to need to change frequently over lifetime, while continuously running

- Adaptability is priority over raw performance

For the best chance of sustained success and happiness follow the microservices principles and ensure that:

- Engineers are empowered and trusted to care for the running system, not only the codebase

- Engineers are empowered and trusted to make technical decisions and to experiment

- The team structure is allowed to evolve with the functional needs of the business

Note that I use the term engineer here rather than developer or programmer for two reasons. Firstly to emphasise that the act of software creation is much broader than code. Also to encompass other potential technical roles than developer - for example architects, test specialists, database experts, DevOps specialists. Whether each individual plays many roles or each has specialism, the cross-functional team is necessary to benefit fully from the microservices approach.

I’m a strong believer in the long-term relationship between software teams and the software products they create. I like to think of it as “living software” - always running but never staying the same. It is in this context that microservices principles and a culture of trust, autonomy and experimentation can help a software organisation sustain a fast pace of change.

Are microservices still the future?

“Are Microservices the Future?” asked the 2014 post on Martin Fowler’s site. Popularity of the term in the market and among our customers shows that the approach continues to be a growing trend in 2020. When will it end? What will replace it?

For the currently popular implementation details such as Spring Boot, .NET Core, or even the mighty Kubernetes, this is hard to predict. With no disrespect whatsoever to these great things, technical implementations come and go. Architectural patterns such as event-driven will likely grow in popularity over more direct internal REST API interactions. A “serverless” future is also compelling, taking the fine-grained approach to new extremes with the added twist of virtually unlimited scaling and an entirely usage-based cost model.

I would argue that these things do not replace but rather add new variety and nuance to the microservices approach. Microservices as a term may well fall out of favour but the principles of decentralisation that support freedom to adapt will endure.