A lot of people are talking about the Data Mesh concept first referenced by Zhamak Dehghani in her blog How to Move Beyond a Monolithic Data Lake to a Distributed Data Mesh. It’s not hard to understand why.

The Data Lake journey has been a bumpy one, as many organisations have tried centralising into a master Data Lake and been hit by many of the challenges that the paradigm brings along with it – including data quality, ownership and accessibility – all of which impede the value of a centralised Data Lake.

On top of that, there is a growing recognition in the industry that if the organisation of IT can more accurately mirror the structure of the organisation, it is more likely to be successful. A good example of this is a microservices approach; this enables technology teams to be distributed across an organisation, granting them greater independence and alignment with the organisation’s business domains. This contrasts sharply with the Data Lake approach, where a centralised IT team typically owns the data.

The Data Lake paradigm is just one milestone on the longer journey that organisations across the globe have been on to find the optimal approach for managing and leveraging analytics data. In this post, I’ll set out each of the key milestones on the journey, to arrive at the latest milestone: the Data Mesh paradigm. And given we’re only at the embryonic stage of this new approach, I’ll ask whether Data Mesh is even really a thing.

But first, let’s define what we mean by a Data Mesh.

Defining a Data Mesh

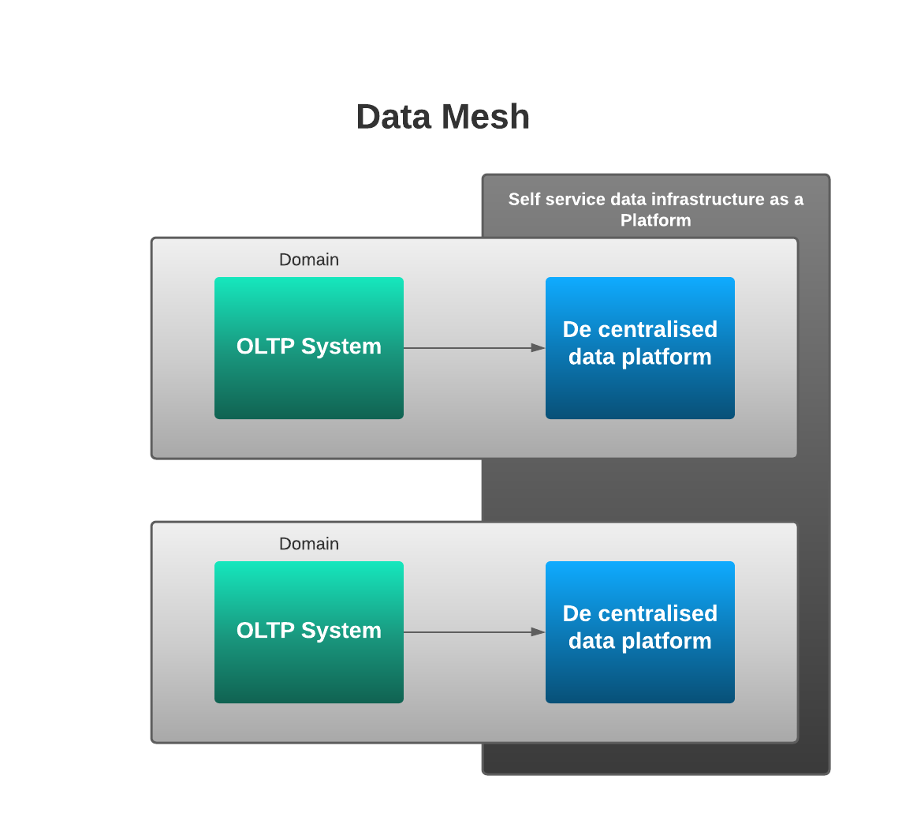

A Data Mesh is a new Enterprise Architecture where the domain teams own the data in the mesh in a decentralised approach supported by a platform. In this way, it brings analytical data and operational data logically closer together.

According to Zhamak, a Data Mesh has four key principles:

- “Domain-oriented decentralized data ownership and architecture” – the domain teams own their own data instead of the ownership and architecture being handed off to a centralised technology team.

- “Data as a product” – treating data as a product involves thinking about others using the data and focusing on it as an asset.

- “Self-serve data infrastructure as a platform” – to facilitate this decentralisation, a self-serve data infrastructure is needed. This platform/infrastructure can very much still benefit from being centralised, but the local IT teams can build upon it and use it to service their own needs.

- “Federated computational governance” – to ensure the data from different domains can be joined together, it is important that the system itself supports the work needed to ensure the domain models align correctly. I personally find “Federated computational governance” confusing, so I will refer to it as “Interoperability of data models across domains”.

To understand why these four principles differ so markedly from previous data architecture approaches and why collectively they make a significantly different paradigm (i.e. that Data Mesh is a thing), let’s take a step back through time: follow me as I trace the journey towards a Data Mesh using the generations mentioned by Zhamak Dehghani in her first Data Mesh blog.

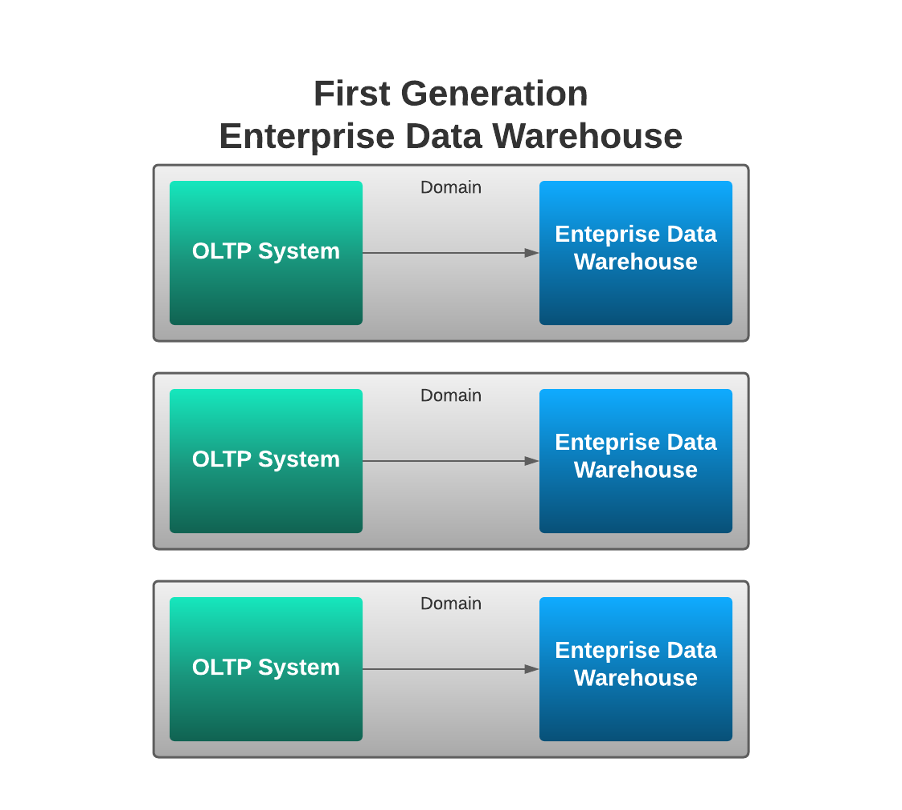

First generation: Enterprise Data Warehouse

Ignoring mainframes, big data has been around for decades. An example of an early use case is from Telecoms: the processing of huge volumes of Call Data Records to generate phone bills. Apart from the bespoke solutions for each sector, the Enterprise Data Warehouse marked the first milestone in the big data journey and became the go-to solution for producing analytics and reports.

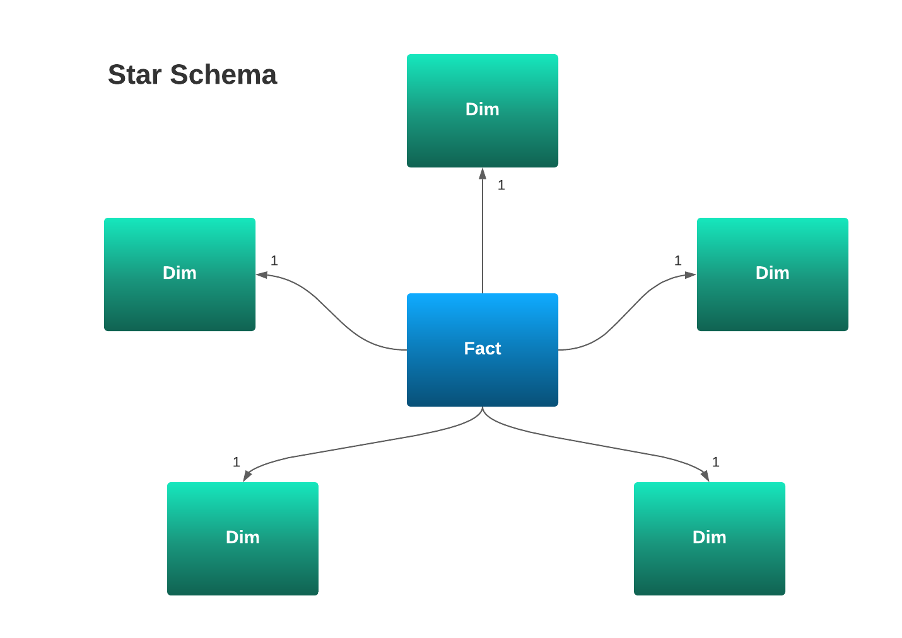

Enterprise Data Warehouses offered fast generation of reports/analytics from large volumes of data, but these benefits typically came with large costs in time and explicit costs in hardware and software licences. Adding tables to a new report in a Data Warehouse typically required ETL scripts to load the extra data in and development work on the warehouse (adding to the current schema, a common approach was an optimised star or snowflake schema that tended to differ from a heavily normalised schema in an OLTP system). This meant new reports tended not to benefit from the general development of the OLTP system (if you added new data to the OLTP system, you then needed to add that data to the Data Warehouse schema and change the ETL scripts).

Enterprise Data Warehouses have evolved a lot over time and their evolution warrants a blog post in itself, but we’ll gloss over the changes and nuances to follow this current line of thinking to help explain the emergence of the Data Mesh.

So, given that the speed of change for the Data Warehouse was slow – requiring Development time and resource – and the licensing costs tended to be very high, this was often a costly solution. And that’s not to mention another issue – the incremental development of Data Warehouses which often resulted in systems accruing a large amount of technical debt.

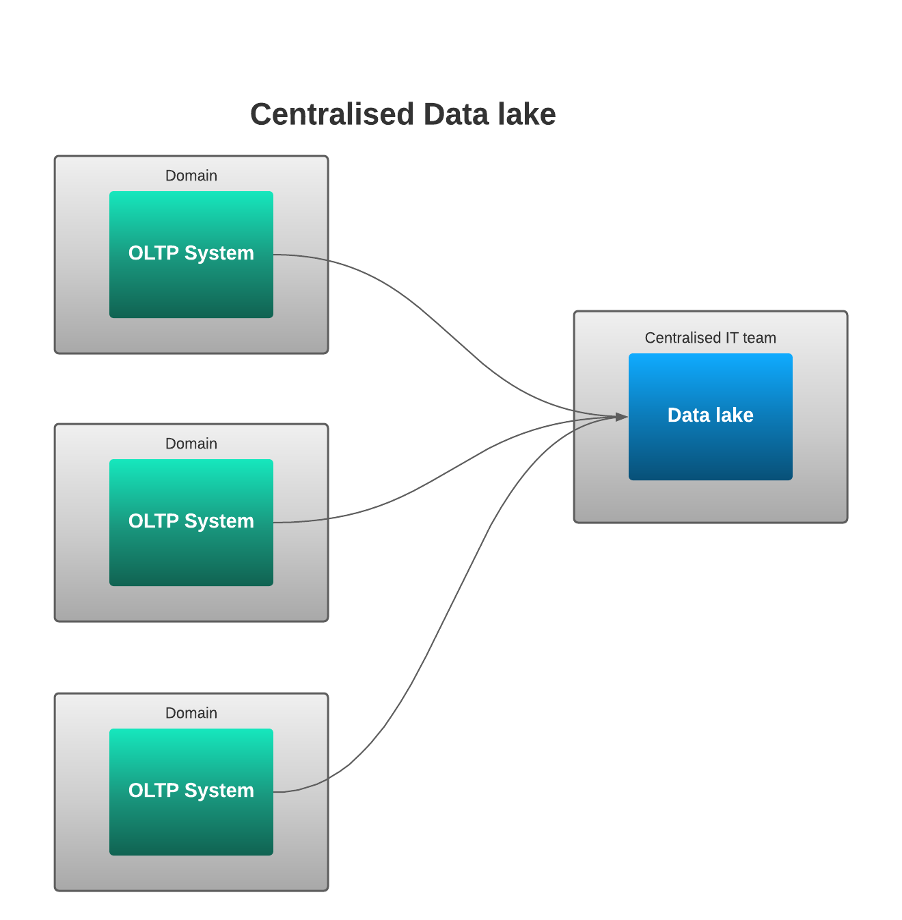

Second generation: Centralised Data Lake

Everything was disrupted in 2005 when Apache Hadoop was built from the design in the Google white papers on MapReduce and the Google File System which offered new solutions to storing, searching and processing large amounts of data.

The solutions were designed for a very particular use case – namely, storing web pages and indexes and being able to retrieve data from them at very high speed (in parallel) on commodity hardware.

The sheer volume of the data being stored (i.e. the output of a webcrawler), and the nature of that data (raw web pages and indexes) meant that an Enterprise Data Warehouse architecture was not a great solution.

Developers at Yahoo took the white papers from Google and built Hadoop which introduced an open source implementation of MapReduce and HDFS (based on Google File System) to the world.

Hadoop enabled a whole new generation of large-scale data storage and processing with four big differences from the Enterprise Data Warehouse:

- It was super-easy to do a new search/report without having to change the structure. The fact that development changes to the data storage weren’t needed to optimise the reports meant that as long as you had the raw data stored in HDFS, you just had to do the development for the report itself.

- It was open source, so there were no large licensing costs.

- It ran on commodity hardware, so offered a huge reduction in the cost per Mb of storage and processing of the data.

- The skills required to write MapReduce jobs and manage Hadoop were very, very different from those required to use an Enterprise Data Warehouse. A Data warehouse required SQL skills which matched those who did development on the SQL OLTP databases.

But the second generation wasn’t perfect. Everyone tended to dump all the raw data into one central place. The cause of this was mostly technical – the specialist knowledge required to maintain the tools and carry out development on them took the data further away from the business. However, the impact was often organisational, with a huge impact on the data quality and its fitness for purpose. While the centralised team owned the data and had the remit to clean it up, they often didn’t understand the data as well as the IT teams who worked on the systems from which the data originated.

The impact of taking the data further from the business can be seen in the challenges in centralised Data Lakes around:

- Access control – Who should see which data? How is that data access applied to a centralised data lake?

- Data Quality – Being further away from the business, how is the quality of that data ensured?

But aside from the impact on data quality and the challenge of access, there were also significant technical challenges which put pressure on the second generation systems to evolve.

One of the biggest technical challenges with Hadoop was that a lot of developers found working with MapReduce jobs quite hard, especially debugging. The skills and knowledge required didn’t tend to match common software development, which meant there was often a shortage of people with the required skills. This, along with the fact that managing the clusters such as HDFS required specialist knowledge quite dissimilar to previous systems, meant the pressure to centralise was very high.

Moreover, the split between streaming and batch processing often cost the Development team time; frequently, they would need to write the same code in both a batch algorithm and using a stream-processing algorithm/framework. A typical example of this would be something like a bill processing system that had a batch algorithm to manage large volumes of bill calculations overnight, and a streaming algorithm to do the same calculation on the fly for the UI whenever a user requested their bill be regenerated due to a change in data. This double keying gave way to the Lambda and Kappa architectures.

Third generation: Kappa and Lambda architectures

Addressing some of the technical challenges of the second generation led to optimisations that arrived at the Lambda and then Kappa (a specialisation of Lamdba) architectures.

The tools and architectural approach for these centralised Data Lakes steadily improved, such that a more unified batching/streaming architecture became the norm, reducing the need to write a lot of the processing twice.

The Kappa architecture simplified the Lambda architecture by making the batch processing a type of stream processing. Plus, the tools have improved so much that the need for specialists to develop on the platform has been reduced; the development technologies have moved closer to those used in Data Warehousing and are more aligned with the SQL standard of old. For example, you can see SQL being available in KSQL (in Kafka), Spark SQL (in Spark), Flink SQL (in Flink), among the numerous technologies which support SQL syntax.

The technology in the third generation is much closer to regular software development. The increased use of SaaS versions of Hadoop, Spark, Flink, Kafka etc. removes the complexity of managing these highly complex clusters. This meant that many of the drivers to stay centralised – including the dependency on specialists – were slowly falling away during the third generation.

However, there was still no technology or defined paradigm to support full decentralisation. This would be left to the fourth generation – Data Mesh Enterprise architecture.

Fourth generation: the proposal of the Data Mesh

Several companies have started experimenting with self-service platforms to enable teams close to the business (the original development teams of the OLTP systems) to support the business better by owning their own data. This move has been named by Zhamak Dehghani as a Distributed Data Mesh.

As the four key principles described above indicate, the Distributed Data Mesh approach is very different from the previous approaches:

- Instead of one centralised model, the domain-oriented models are owned by the IT teams/business.

- Data is treated as a product itself, and systems need to be in place for the business to manage this data as an asset.

- There needs to be a self-serve infrastructure platform that the IT teams can use to store the data, and host the processing of it and access to it – this ensures that it isn’t just disconnected collections of data with no easy way to combine it when needed.

- There needs to be a systematic way of ensuring the models link together so that data between domains can be joined up, like in a centralised Data Lake.

The promises of the Data Mesh approach include:

- Better data quality as the business owns the data as a product, and is driven to ensure it remains high quality.

- The analytics data is back with the domain-oriented IT teams who understand the data better and are close to the business.

- The access control models in the OLTP systems can more easily be mirrored into the storage for the analytics systems.

There is still a lot to unpick around what precisely a Data Mesh is, so I will look more closely at the four principles and their implications in a future blog post.

But for now, let’s go back to our original questions: what is a Data Mesh? And is it a thing? I hope I have demonstrated that a Data Mesh is a different architectural approach from the generations that came before. It contains significant changes in who owns the data (the teams who own the OLTP systems and the business), how that data is treated (as a product), and in relation to the approaches/platforms that enable data to be used across domains.

I believe it is sufficiently different to be a distinctive change, and therefore that it is definitely a thing.