…or what I should have known before I jumped in

I recently received an invite to try out the OpenAI API beta. As always, I jumped straight in and started playing around. By tweaking the examples I was able to produce some interesting and/or entertaining results.

However, after a little while I realised I didn’t really understand what was happening or what the various parameters really did. So I jumped into the docs and read/watched around the subject. This mini-series of posts are a summary of what I’ve learnt -

- Part 1 (this post) covers the basics of tokens, the model and prompt design.

- Part 2 covers logprobs and the “creativity” controls.

- Part 3 covers few shot learning and fine-tuning.

If you were hoping for examples of what it can do, this isn’t going to be for you. I’d recommend checking out the impressive examples in the documentation.

Introduction

The OpenAI API (what a mouthful!) provides functionality which is quite unlike any other service I’ve interacted with. At its core is the completion API. It provides the most direct interface onto the trained GPT-3 models which power the whole service. But what is a GPT-3 model and what’s so different about it?

At a high level, the GPT series is a set of language models which try to predict the next word in a sequence. This might not sound that impressive, but in the case of GPT-3 that sequence could have been drawn from many terabytes of text data covering the whole of Wikipedia, large numbers of published books and huge swathes of the internet.

It follows that for the model to perform well during training, it had to internalise significant amounts of general knowledge, writing styles and languages. It also has to be able to accurately parse the prompt, which can span many paragraphs, in order to apply that understanding appropriately when predicting a completion.

Crafting prompts is a bit of an artform that even a year after the service launched, is not fully understood. However, there are a number of impressive examples available to review. In this post, I’ll mainly focus on the options available, covering their background and how to use them.

Tokens

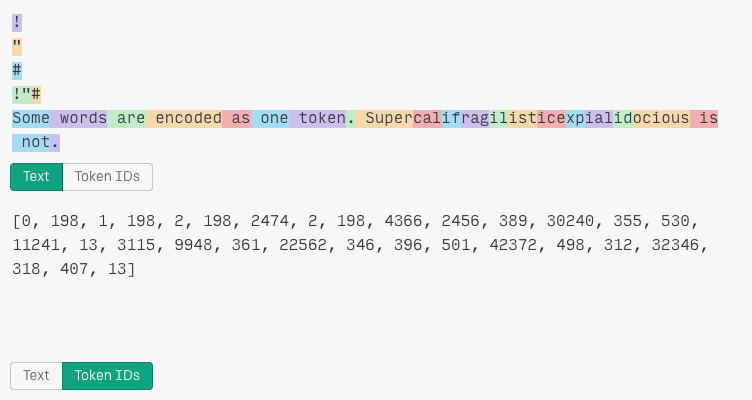

It’s impossible to get far with the OpenAI API before you run into the concept of tokens. I did my best to blunder on regardless, assuming it was a complicated topic. It turns out not only was I wrong but I found tokens to be one of the easier topics to wrap my head around. So what is a token?

When I’ve learnt languages or witnessed smaller, more vulnerable germ-factories learning languages, whilst some focus is given to learning the individual letters, a lot more focus tends to go on the sounds that make up words. Those sounds tend to be the building blocks of language, rather than the individual letters they are made of.

Somewhere between these sounds and journalistic shorthand, is the best (short) explanation of tokens I can think of. A common sequence of characters is abbreviated into a single token. Sometimes this can be full words, parts of words and in less common situations, individual letters. All of these tokens are stored in a big lookup table which maps character sequences to positive integers.

Importantly these sequences of characters tend to include leading whitespace. For example, "text" (which has the token identifier 5239) is a different token to " text" (2420). This has massive implications for structuring prompts for the model which we’ll come onto later.

Engines

Any AI-powered service will be backed by one, or more, models. I think of a model as a set of interconnected nodes, and training as a search for the optimal parameter values for each of those connections.

By choosing different numbers of nodes and connecting them in different ways, there are an infinite number of ways of structuring a model. These structures are called model architectures and designing them is a highly-skilled, multi-dimensional compromise of potential model capability against training time.

In the case of the OpenAI API, when making a request to the API, you choose from one of these Engines (aka models e.g. Ada, Babbage, etc.). In doing so, you are choosing the relative size of the model (in terms of nodes and connections), its prior training regime (e.g. what set of texts it was trained on, how long it was trained for, etc.) and how much you’ll pay per-token (both prompt and completion tokens are billed). The documentation has a good breakdown of all the available models, some of which are general purpose and others which are more specialised such as the codex series which were trained on code or the instruct series which were trained on instructions.

All of these models are based on the transformer architecture. There are lots of interesting characteristics of this design but I think of its key feature as being its lack of internal state when generating completions. So how does it work?

This post assumes GPT-3 token encoding which is used by most of the engines. However, the codex series use a different encoding which can more efficiently encode the whitespace typically found in code. For example, " if" is encoded as 4 tokens (" ", " ", " ", " if") by the GPT-3 encoding and just 2 (" ", " if") by the codex encoding.

Basic prompt design

Let’s consider a simplified invocation of the model, with the prompt text "Once upon a" -

model(tokenise("Once upon a")) == tokenise(" time")[0]

Firstly tokenise converts the text into a sequence of tokens [7454, 2402, 257]. This sequence is passed into the model and it produces a single token 640 which equals the text " time".

To generate the next token, because the model has no internal state, we just concatenate the output onto the original input producing the sequence of tokens [7454, 2402, 257, 640] and re-invoke the model -

model(tokenise("Once upon a" + " time")) == tokenise(",")[0]

With this understanding that the model generates a single token at a time, I was able to infer that sequences of tokens must be generated within a loop. Therefore I was able to wrap my head around a few more of the request options -

Response length- the maximum number of iterations of the loop i.e. the number of times the model will be invoked and therefore the number of output tokens.Stop sequences- one, or many, sequences of tokens that will cause the loop to break early.

In summary, sequences of tokens are presented to the model as inputs which produces a token as its output.

Trailing whitespace

Remember I said that whitespace really matters when structuring prompts? Well, now I can give an example of why. If the original prompt had a trailing space ("Once upon a ") it would produce a different sequence of tokens [7454, 2402, 257, 220].

Whilst it is reasonable to assume that a human would still complete this with "time" (2435), the model will not. That’s because in its training examples "Once upon a time" is always encoded to [7454, 2402, 257, 640], so this alternate sequence of tokens will only rarely have been encountered (e.g. exotic whitespace in a poem or the like). This low occurrence in the training data will result in the most commonly occuring token being output instead "\t" (197).

I think it is fair to say that this is firmly in the realms of - it’s a feature not a bug… honest! My assumption is that using the tokeniser simplifies the model, by externalising this knowledge at the cost of unintuitive behaviour such as this. However, at 175 billion parameters, I can forgive GPT-3 the odd simplification.

Conclusion

When I first played with the API in the playground, I quickly learnt not to end my prompts with whitespace. However, I was only doing so to placate the annoying warning message that popped up, I had no real understand of why I needed to do it and I found that incredibly frustrating.

Hopefully this post has saved you from that same fate, or at the least, inspired you to keep reading about some of the more interesting options I’ll cover in part 2. In the meantime, here’s a great OpenAI blog post covering an alternative application for a transformer architecture.