The recent Log4j vulnerability has once again sparked a lot of debate around our reliance on open source projects and their sustainability challenges. In this blog post I argue that money cannot fix this issue, nor can hiding behind security scans, audits and other defenses. The solution is to genuinely understand the open source community, acknowledge the shared responsibility we have in our commons and through the well-understood tool of Corporate Social Responsibility, look to fill the ethical and philanthropic gaps.

If you’ve not heard of the log4j vulnerability (where have you been this last week?), allow me to briefly summarise …

Log4j is an open source logging framework that has been a de-facto part of the Java stack for two decades. One week ago a vulnerability was identified that allows attackers to load malicious code into an application via a simple JNDI URL. As a result, any application that logs user input (e.g. chat logs) is vulnerable. The impact of this vulnerability is widespread, the Google Security team estimate that 8% of Java packages are affected, leading to disruption impacting many critical services including cloud providers, government and education bodies.

As the maintainers of Log4j scrambled to fix this issue (together with an additional two that have been identified since) it emerged that the project was maintained by a team of three developers, on a part-time basis. They had a GitHub sponsorship page for the project, with a grand total of three sponsors, earning barely enough to buy the team a round at Starbucks!

The impact of this vulnerablity has drawn comparison to Heartbleed, the OpenSSL security hole that emerged nine years ago and caused significant disruption, shutting down hospital’s computer systems. In the aftermath of Heartbleed the Core Infrastructure Initiative was formed in an effort to identify and support critical open source projects. The group (renamed to OpenSSF), recently published their methodology for identifying critical projects, with 200 Java projects making the list. Log4j was not among them.

This ‘focussed’ approach to fixing the issue clearly isn’t working. In my opinion, any project within your software bill of materials, or supply chain, should be considered critical.

So what is the solution?

💰 Money

Surely money is the answer, is there anything you can’t solve by throwing money at it?

A year ago I performed my own analysis on a popular open source project, ExpressJS, asking myself important question such as, is this secure? is it sustainable? who wrote this code? Question that I keep coming back to time an time again.

So I just installed the latest electron / react boilerplate, and it has 108 direct, and 1,861 transitive dependencies.

— Colin Eberhardt (@ColinEberhardt) July 15, 2021

This is a problem.

A thread about the fragile, bloated, insecure ecosystem we are building.🧵

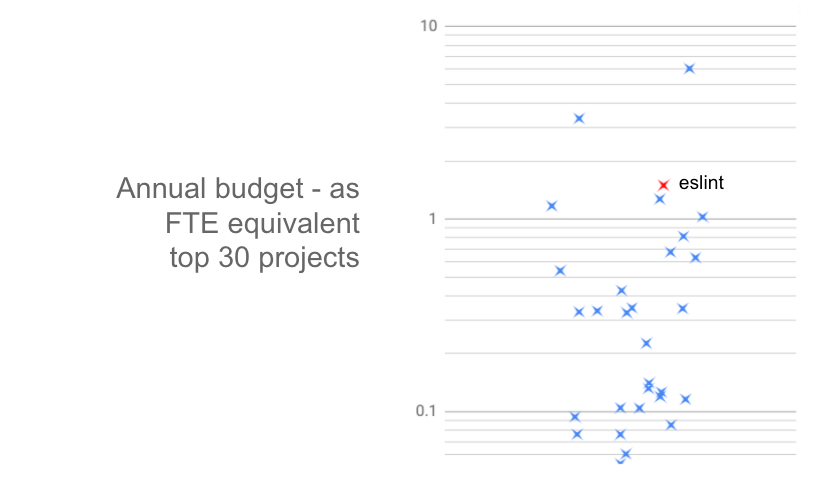

ExpressJS is comprised of over 200 open source projects. Of all of these only one has a funding model, via the popular Open Collective website. Looking at the top 100 projects on the Open Collective site, only six of them earn enough to fund a single full-time developer.

To contrast, a recent OpenUK report estimated that open source contributes £43.1bn to the UK economy - while Open Collective and Tidelift, the two leading open source funding sites, collect roughly £40m annually. That’s quite a gap.

If we assume money is the solution (which it isn’t, more on that later), there clearly isn’t enough money flowing into open source to fix these issues.

🏰 Build your defenses

Unfortunately the most common approach I’ve seen to the open source sustainability issues, at least from large enterprises, is somewhat medieval - build a great big defensive wall around your riches!

Tooling for cataloguing, CVE management and automated analysis is big business, with Black Duck recently selling to Synopsys for $565m. If you can’t fix the sustainability issues, you can at least create ‘clean’ copies of this code and keep it safe within your castle.

This is clearly wrong. To quote Feross (a well know open source maintainer):

So this means that they charge a 50-person startup a whopping $30,000 per year to help them feel safe using code that open source authors like me have given away for free.

If it’s not fun anymore, you get literally nothing from maintaining a popular package.

🔄 We need a new direction

Clearly we need a new direction - our current approach isn’t working.

Firstly we need to change the way we think about the problem. As mentioned previously, money is not the answer. To find out why, we need to gain a much better understanding of the problem itself, and to do this we need to gain a better understanding of the community that have created so much of the open source code we rely upon.

I’m not going to delve deep into this topic, instead I am going to recommend that you buy a copy of, and read “Working in Public” by Nadia Eghbal. I learnt so much from this book.

🏆 Attention is the most prized asset

One of the key learnings I took away, which is pertinent to the challenge of sustainability is that attention is the open source maintainer’s most prized assets. Attention is limited, and maintainers wish to use it on the tasks they find most rewarding. Conversely, activities which steal their attention (aggressive behaviour, people who feel entitled to a bugfix or response, etc) cause lasting damage.

A great illustration of ‘stealing attention’ happened last year during Hacktoberfest, a well-meaning project sponsored by Digital Ocean where open source contributions are rewarded with T-Shirts (what could possibly go wrong?!). Unfortunately maintainers of popular opn source projects were bombarded with low quality pull requests to the point where they declared Hacktoberfest a distributed denial of service attack on the open source community.

On a more specific note, last month I wrote about a recent open source survey we undertook within financial services. We found that identifying and resolving security issues was the biggest obstacle to open source adoption (by large fnancial service organisations), yet open source maintainers only spend 2.27% of their total on security issues, and they reported that they do not desire to increase this significantly.

To protect open source we must understand the motivations of the community that built and help them preserve their limited attention.

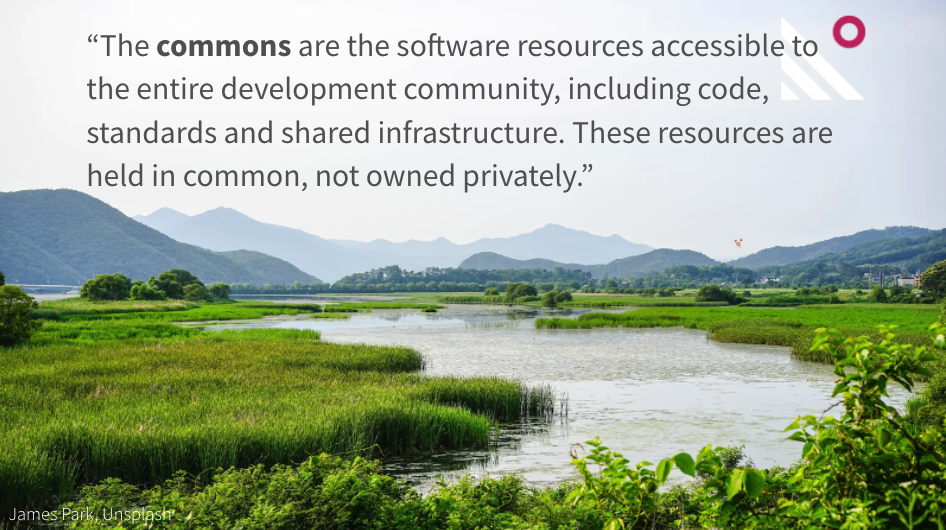

🌳 Open source is our commons

Another key change we need to make is to our overall perspective of what open source is - it isn’t just a pile of code thrown up on a website. It is a valuable resource that is accessible to everyone, often maintained by volunteers, oftentimes simply because they see an inherent beauty in what they have created.

There are very strong parallels between the open source community (and the projects it creates) and the definition of the “commons”

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable earth. These resources are held in common, not owned privately.

With just a few small tweaks:

The commons are the software resources accessible to the entire development community, including code, standards and shared infrastructure. These resources are held in common, not owned privately.

Now that we have shifted the language away from money to understanding and empathy; and from code to community and the commons - let’s start talking about our responsibility.

🏛️ Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility (or CSR) emerged in the 1960s as a way of codifying the responsibility companies have with respect to various societal goals. Whilst it was initially introduced as a form a self-regulation, social responsibility is increasingly legislative. For example, in the UK, government procurement processes require that contracts in excess of £5m can only be awarded to companies with a published carbon reduction plan.

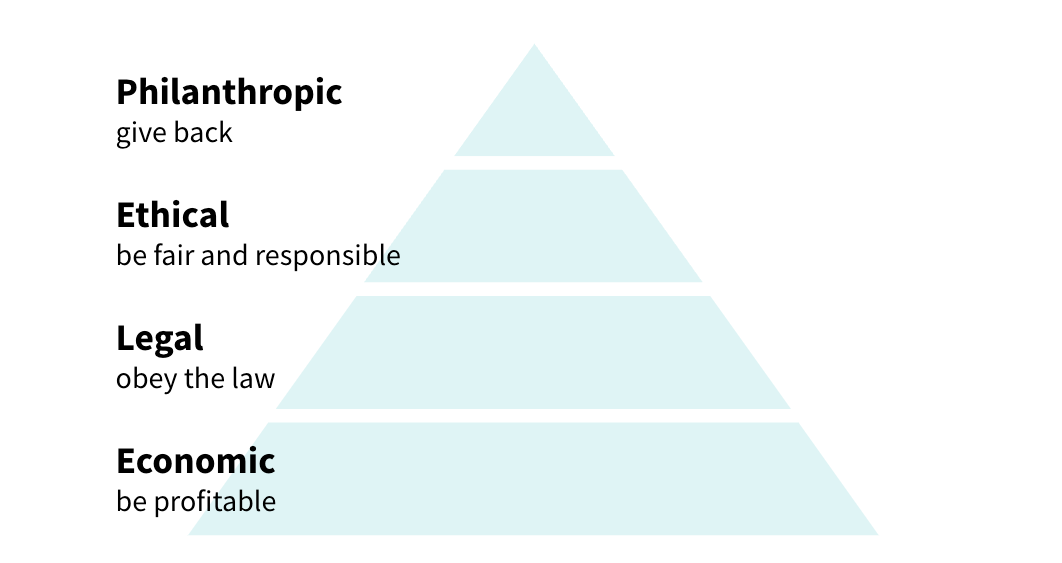

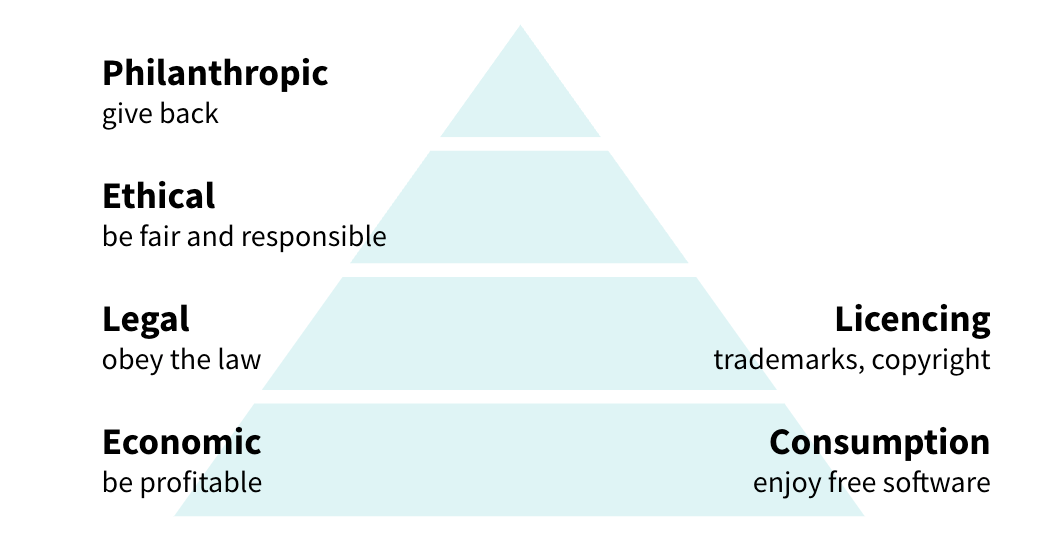

The various components of a business’ responsibility are neatly captured by Carroll’s Pyramid:

Whilst the foundations of the pyramid are mandatory, a company needs to be economically viable to survive and must also be compliant with the law, the top two layers are optional. Through CSR, companies are encouraged to act ethically; be fair and reasonable, consider the impact their decisions have on others. Finally, at the very peak of the pyramid, they are encouraged to give back, be a net positive contributor. The ‘commons’ very much benefits from CSR.

So why not leverage this same model for protecting the open source commons?

In my experience, this pyramid does exist, but there are gaps:

The economic case of open source is quite clear, generally speaking it provides an financial advantage by lowering the total cost of ownership. In many cases it is simply free. When it comes to the legal aspects, again this is quite clear, open source licenses and patents are straightforward and well understood.

But what about the ethical aspects of open source software? Is it fair that the burden of responsibility for ensuring a project is secure falls entirely on the shoulders of unpaid maintainers? No. It is not.

What about philanthropy? How many companies can honestly say that give back as much as they take from open source? How many of them are protecting the commons?

My hope is that through the well-understood vehicle of Corporate Social Responsibility, business will wake up to the shared responsibility we all have for maintaining this precious, yet fragile, resource we have become so deeply dependant on. The problem is not one that can be solved by throwing money at it. We need to better understand the open source maintainers and their motives - I gave an example earlier of how they value and protect their attention. Through genuine understanding and a deep willingness to help, I’m sure we can find a solution.

Regards, Colin E.