Humans are causing climate change; a statement that more people agree with today than ever before in human history. The knowledge that Green House Gas (GHG) emissions are the cause of this change is also growing. So this blog is going to focus on understanding where software, the people who develop said software and GHG emissions intersect.

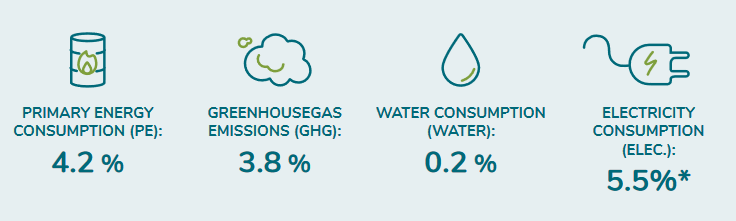

The world is now dependent on the digital sector, whether that be phones, computer screens or data centres. To start with a scale, it is estimated that this sector emits 3.8% of the total Green House Gas emissions (GHG) of the planet. Everyone needs a bit of context, so that is more GHG emissions than Japan - the fifth biggest contributor. The sector’s contribution is therefore considerable, and unsurprisingly this is a sector that is predicted to continue growing substantially.

Footprint of the digital world

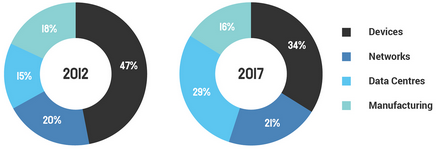

The internet - it’s a pretty big deal. The many benefits of the internet, you getting to read this blog post etc., are well documented. It has been described as the biggest machine ever built. I don’t know how someone worked this out, but I do know that it has over 4.5 billion users. Cloud data centres are a key component of this machine, and themselves consume 1% of electricity used globally. In 2012, data centres share of electricity used by the internet was 15%. By 2017 this had grown to 29%. There have been great strides to optimise these data centres by the big tech firms like Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft. The biggest source of energy use for these data centres is cooling, so Facebook set up one data centre in Lulea, Sweden.

Breakdown of the internet’s footprint

As a software developer it is very easy to claim that all of these emission problems are hardware and energy problems; it’s the running of the machinery and how the energy required to run that hardware that is the issue. Can software actually make a difference? You can’t improve what you don’t measure, and currently there is no HTTP header returning the total amount of carbon emitted to return data from an endpoint. Google, however, now has a Carbon Footprint tool to allow users to measure and visual the carbon emissions of their cloud usage. For that tool to be effective, developers have to actually use it.

In a capitalist world, the value of things is usually a good indicator of how important humans value something. Over the last decade investors have lost $123bn by investing in fossil fuel producing and related companies, while investors in renewable energy/cleantech have gained $77bn. So who are these silly people still investing in fossil fuels?

In the UK, it’s most people who have a pension. If someone is paying into a pension that isn’t specified as ‘Sustainable’ or something, well then it’s probably going to be somewhat invested in fossil fuels. An estimate places the investment in fossil fuels from UK pensions as £128bn. It’s likely that very few people paying into their pension even know their actually funding climate change.

This makes one of the most powerful steps that any individual can take to living more sustainably is to simply opt in to their pension providers ‘Sustainable’ fund instead of the default. Almost every major UK pension provider now has this fund option. So if every UK pension contributor made this change, all that investment wouldn’t flow into fossil fuels. One question you may have is, “Why don’t employers enrol employees into the sustainable fund by default when they set up the pension?”

It may seem inevitable that when discussing software and the environment that bitcoin and NFTs would be involved, seeing as they’ve been making headlines over the last couple of years. These headlines, however, are the exact reason that they have been omitted, as they have been covered by much more intelligent people in far more detail than could be covered here. These are two brilliant articles on the environmental impact of bitcoin and NFTs.

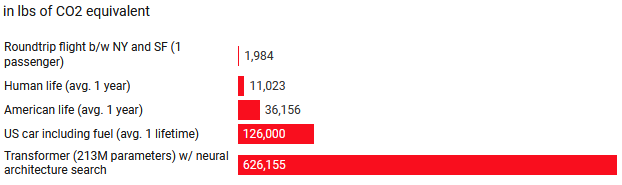

Another interesting technology is Hollywood’s absolute favourite, Artificial Intelligence. This is, however, a good example of where the development of software has a genuine carbon impact, rather than the use of the product once created. Training a single neural network model can emit roughly the same amount of carbon as the lifecycle of five standard American cars (including manufacture). Understandably there are no plans to limit the use of AI in the future, just worth understanding the potential cost of this technology. Could utilising AI to tackle environmental problems cause more harm than good?

Carbon footprint benchmarks

COVID-19 was significant. It finally convinced all employers that when the employees told them that they could work just as well from home as in the office, that they were telling the truth. This, in part, is due to the remote tooling (Zoom, Teams etc) improving to a sufficient standard. A side effect of this remote migration, in the UK at least, was a reduction in commuters. Transport contributed to 27% of the total UK emissions in 2019. The overall emissions from the UK in 2020 were down 4-7% compared to 2019, and so some of this reduction may well be attributed to this change in commuter habits.

People working from home now use more emissions to heat their house due to spending longer in it, as well as little things such as cooking lunch. They also are utilising more energy using those working from home tools, for example Zooming a work colleagues using their work laptops rather than wondering over and convincing them to take a break from their work to have a real life chat. However, the overall emissions of the UK have reduced, so it stands to reason that these extra emissions from working from home are still less than the emissions saved from the commute. With electric cars set to overtake the sector, and fewer commutes overall, transport looks in a good place.

Covid, as mentioned, was significant. It is estimated that in 2020, the global emissions fell by largest annual percentage decline since World War II. So taking a moment to think about these two events which triggered the largest decrease in emissions, what do they have in common? Could we derive a singular solution to solve the emission crisis from that?

I hope that the rambling exploration of a few areas where technology intersects with the environment have been interesting. Some areas have solutions currently being implemented; some areas have solutions that are yet to be implemented; some areas still have no solutions. This blog was not intended to convince you either way that climate change is a problem we can solve or not, it was merely a chance to introduce people to how technology can have a real impact on the environment. It has, hopefully, also shown how indirect this impact can be, and also how in order to use technology to better the planet we are going to have to be brilliantly clever. Feel up for that?