![]()

An introduction to Markdown

Markdown is a brilliant tool for quickly writing up universally accessible documents. Created by John Gruber and Aaron Schwartz in 2004, it stands as one of the most popular and widely used markup languages around. It uses simple and intuitive formatting that can be easily read and understood.

“A Markdown-formatted document should be publishable as-is, as plain text, without looking like it’s been marked up with tags or formatting instructions” John Gruber, creator of Markdown (Source)

A Markdown file can be used for just a quick to do list, written and used exclusively in it’s raw form. But it can also be a well organized and formatted space for ideas, documentation and a range of other things once utilized correctly.

Markdown’s rise in popularity

Before Markdown became widely used, writing straight to HTML was the accepted way for publishing on the web. As a tag-based markup language, raw HTML was (and is) not pretty to read. It includes a large variety of tag choices and often achieving simple things such as bold text embedded in a paragraph can make content illegible to the writer. When Markdown was released, it’s design solved this issue for many, especially among writers who were not developers. For those who adopted to use Markdown, writing on the internet was now easier and faster; removing the need to be proficient in HTML. This accessibility and readability was it’s main driver into popularity.

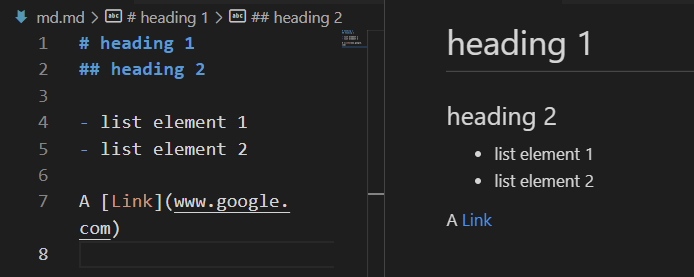

Core tools in the Markdown language

Markdown comes with a myriad of syntax rules for organizing. By far the three most common tools you will use when writing in Markdown are lists, links and headings.

Adding these three components to your document is fast, easy and legible. Typically when I write meeting notes, quick checklists or timeboxed research all I use are these 3 tools. Being able to simply copy and paste the text to another space (a key strength of all markup languages) removes formatting issues experienced with more sophisticated text editors.

Markdown flavours

As more people began to use Markdown for specific needs, the demand for new features in the language grew. Enter Markdown flavours - a range of extensions on the language increasing it’s capability and utility.

When Markdown was released the syntax was not specified unambiguously. Often documents would render differently across different systems due to the variety of Markdown’s rule set interpretations. CommonMark is a modern day solution to this ambiguity, specifying a standard specification for users of Markdown. This allowed easy conversion of Markdown files to HTML across different systems and safe syntax extensibility.

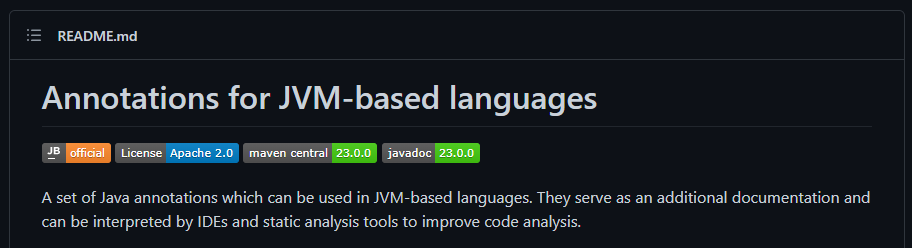

As a developer an example you have most likely encountered before is the GitHub Markdown flavour, a superset of the CommonMark specification. This flavour adds many useful changes relevant to the software world, such as highlighting for a range of programming languages within a Markdown code blocks. By simply adding the language to the start of the block, code snippets can be coloured and formatted as the language would.

Other additional tools include checklist items that can be interactively checked off and text strikethrough for clearly deprecating comments or wording without removing it. As a Markdown flavour, the GitHub flavour interpreter is able to successfully compile these additional features to HTML for use on GitHub.

Real world usage of Markdown

Due to its ease of translation to HTML and readability, lot’s of websites use it for messaging, documentation, blog posts and more! Website’s like Reddit store all posts and comments as Markdown files, giving users lots of choices for formatting their communication on the site. Even Scott Logic’s own blog site (with the Kramdown flavour) allows Markdown blog posts!

Markdown was designed to be compiled to HTML as it’s primary function. This makes it great for static websites such as blogs and documentation. Static site builders like Hugo and Jekyll take this a step further, enabling easy and quick site building where pages can be designed and written straight from Markdown. With almost no handwritten HTML and mostly Markdown files with the styling rules and content, static websites can be quickly created using these tools.

All GitHub repositories include a Markdown README.md. Alongside all other extra syntax rules included with the GitHub flavour, these Markdown files support additional community-made widgets, or “badges”. These can display information such as page traffic and package versioning. A good example of one of these tools is the visitors badge, simply a counter for the number of visits to a specific page. For examples on how people use badges see shields.io.

Creating content for the web isn’t the only use people have for this markup language. Using Marp users can create presentations from Markdown. Additional rules are included to dictate the structure and look of the presentation, with all the styling content and slide transition preferences contained within a single .md! It is also easy to create print ready documents of Markdown files in a variety of formats using conversion tooling like Pandoc.

Final thoughts

Ultimately your use of and interaction with Markdown will likely be dictated by what digital tools you use, be it on a Stack Overflow thread or personal blog page. Personally, I believe it’s greatest strength to most people is through its use as a note-taking tool. I encourage you to explore some of the note taking tools that support Markdown, such as Notion and Obsidian. These are great for organising notes, and even it you don’t use/dislike a tool you can always move .md notes between them later. Once you’ve learnt the syntax, writing quick, widely supported and convertable content in Markdown is a snap.