The Internal App Portal Project

What do you do when you’re a software consultancy that uses small, internally developed applications, and you need to be able to spin those applications up on demand? You build something!

Part of life at a consultancy means stints on the bench, allowing us to participate in internal projects. One of those projects is the ‘Internal Application Portal’ (IAP). A team of developers and testers, often rotating due to being pulled onto client projects, have researched, designed, and built a web application for internal use, which deploys containerised versions of our small applications on demand.

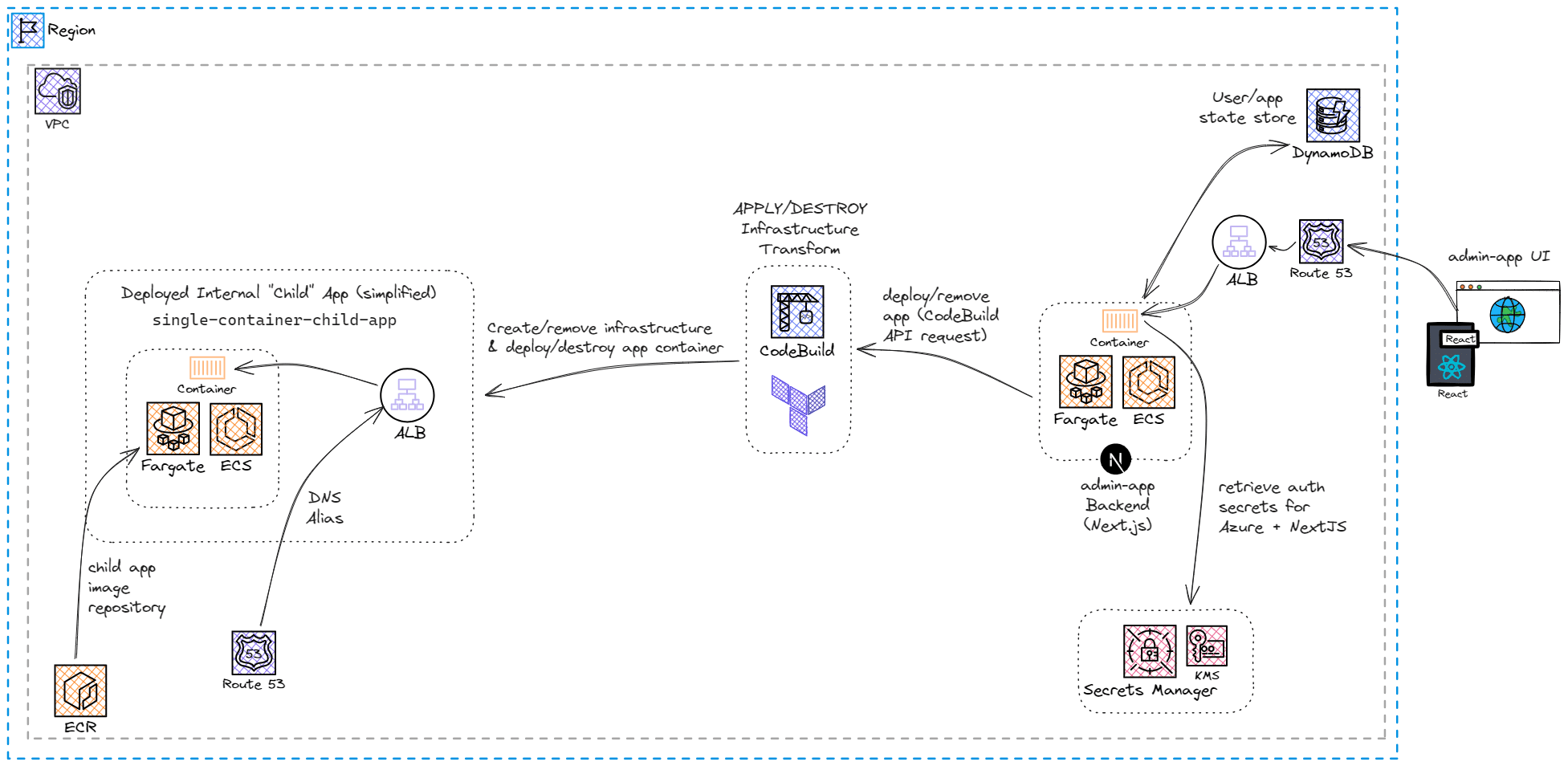

The IAP consists of a Typescript, React, and NextJS web application, deployed on AWS. The small apps, known as child apps, are containerised, and the images are pushed to ECR. From the main IAP web app (the admin app), the user clicks a button, which sends a request to AWS CodeBuild through the SDK, triggering a build.

CodeBuild is AWS’s fully managed continuous integration service. Developers can configure build jobs, and then CodeBuild runs the build scripts, without needing to configure servers. In the case of the IAP, CodeBuild runs the child app Terraform scripts, which then deploys the infrastructure to host the child apps. The child app Terraform scripts are stored on S3, which are zipped and pushed when the IAP Terraform is deployed.

Among the requirements of the IAP project are that the child apps must:

- Be ephemeral

- Be able to be destroyed

- Have unique URLS

- Only have one instance deployed for each user

These requirements mean that the IAP must keep track of the state of the CodeBuild build jobs for the child apps.

Initially, the build job status was retrieved by polling CodeBuild, using SDK. Polling has its limitations and felt like a clunky way of doing things, so we looked to AWS, which would surely have a better solution.

EventBridge

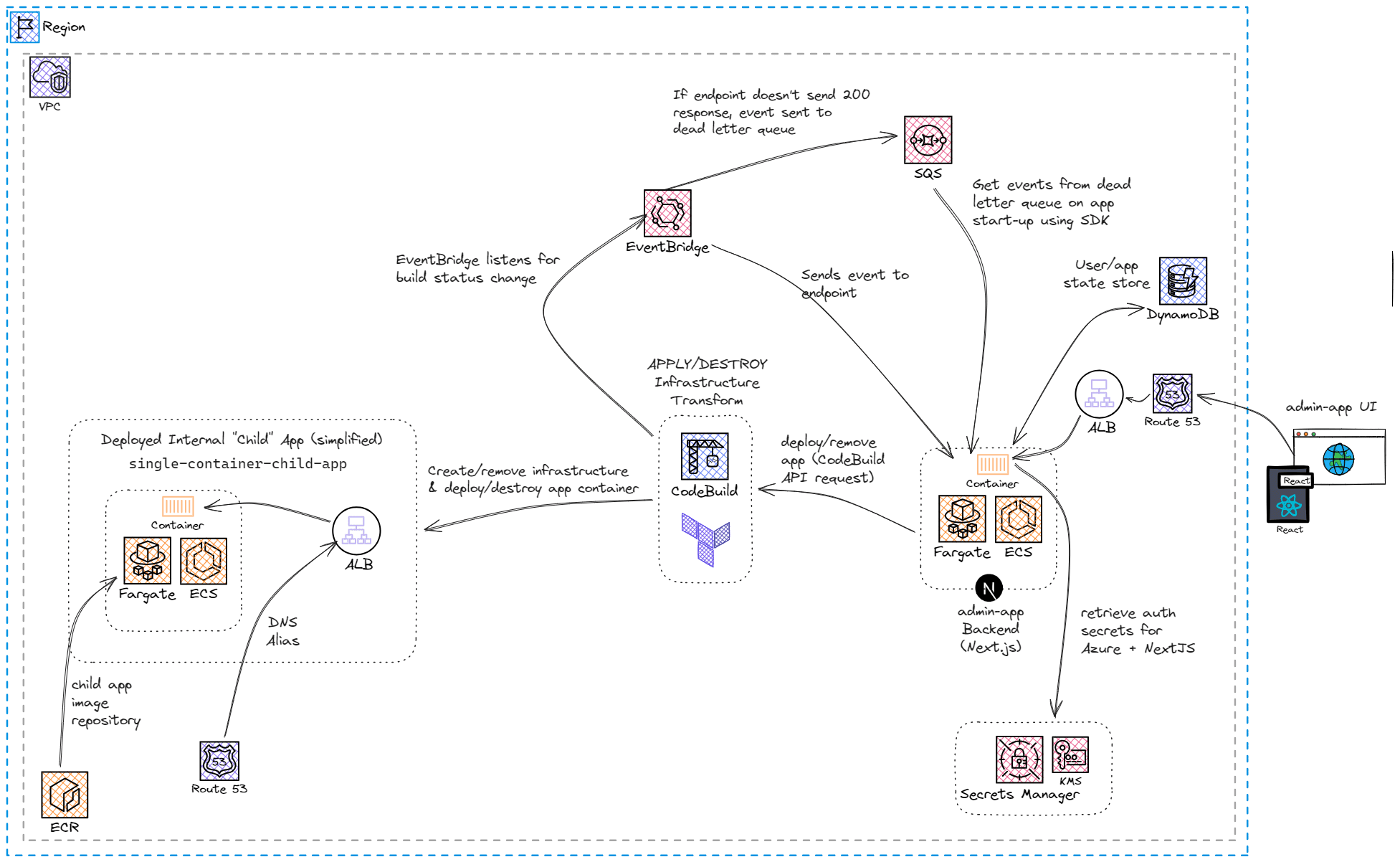

A vast majority of AWS services generate events when there is a change in the service or application. AWS EventBridge can have rules that listen for certain events; for example, a rule could listen for when an EC2 instance changes from ‘Pending’ to ‘Running’. In the case of IAP, a rule was created to listen for the status change in the CodeBuild build job.

The EventBridge rule was configured to send the event to an endpoint in our NextJS app, which stored the details in DynamoDB. The team decided to use DynamoDB as the source of truth for the CodeBuild build status so that if the NextJS app went down, the status of the child apps wouldn’t be lost.

Talking of the app going down, we needed to think about redundancy, and what happens if the app goes down whilst a child app build is running. EventBridge can use SQS as a dead letter queue (DLQ); if the endpoint doesn’t return a 200 response, the event is sent to an SQS queue. After a glance at SDK, it seemed we’d be able to get the events from the DLQ - happy days! (Side note, how many TLAs can I fit into this blog post?)

The issue and the lesson

When implementing the DLQ logic, we discovered that the SQS ReceiveMessageCommand only gets up to 10 messages from the queue. If there are less than 10 messages, you may only get a sample of them, for example, if you have 6 messages in the queue, you may receive 3. To ensure you get all of the messages from the queue, you have to repeat the request… and reimplement the original polling, this time with extra AWS resources and steps.

A small glimmer of hope appeared when we saw that there is a ‘first-in, first-out’ (FIFO) queue type available, which quickly died when we discovered that a FIFO queue could not be configured as the DLQ for SQS

Although the chance of a user deploying a child app, and then the app going down before the response can be sent, was pretty small, especially for the internal once-in-a-while use case of the IAP, it was still causing concern and a reason to go back to the drawing board.

There’s a lesson here though - don’t have a glance at SDK and just assume it will work how you think it does!

Step Functions

To truly understand where we were going with the event-driven architecture and come up with an alternative solution, we took a step back and had a look at what we required. These were:

- The user can load the current state of the child apps

- The user is updated “instantly” when the child app state changes

After picking the brains of some clever consultants in the company, the team started to look at AWS Step Functions.

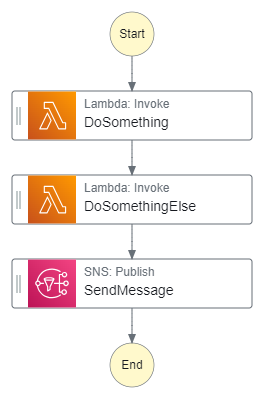

Step Functions is an AWS service that provides serverless orchestration for other AWS services. A workflow, known as a state machine, runs a series of event-driven steps. These steps are generally tasks done by other AWS services through the AWS API, but Step Functions can also call out to external APIs. A state machine allows users to chain multiple lambdas and API calls together whilst preserving the inputs and outputs. The state machines are written in JSON format, but Step Functions has an easy-to-use UI to drag and drop steps.

For example, you may have a state machine that is triggered when a file is added to an S3 bucket, which then runs a series of lambdas to manipulate the file in the bucket, and then sends a notification to a user; whilst you could do this flow without Step Functions, the UI makes the flow easy to visualise, the state machine preserves inputs and outputs, and just makes the whole process a bit nicer.

Two steps forward…

A few investigations and proofs-of-concept later, the team had ideas for using Step Functions instead of the EventBridge/SQS architecture, as well as cost estimations that showed that the two designs had very similar (minimal) costs.

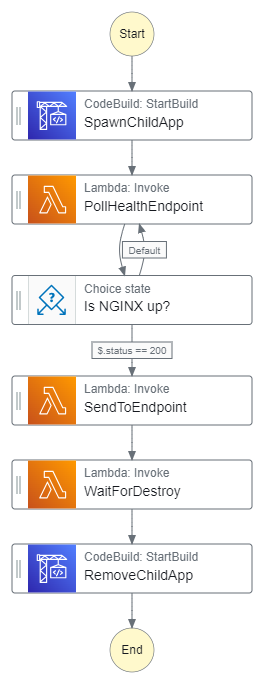

The initial idea was to use Step Functions for the full lifecycle of a child app. Instead of the NextJS admin app sending a request to CodeBuild to start a build, the admin app would trigger a Step Functions state machine. The state machine would trigger the CodeBuild job to deploy the child app, Step Functions would wait for the user to request to remove the child app, and then trigger the destroy job.

Like the example S3 workflow above, we can already do this basic CodeBuild deploy/destroy without Step Functions. We thought Step Functions would give us a few nice things over the then-current solution:

- Easier to add nightly shut-downs of the child apps

- Easier to add health checks for the child apps to ensure they are fully deployed before giving the URL to the user

- Able to use Step Functions as the source of truth for the app build status, rather than DynamoDB

Our rough idea for the state machine was something like this:

… One step back

Of course, nothing is that simple, and we discovered problems with our ideas.

We first investigated how to handle user input with Step Functions - the answer here is callbacks and task tokens. If you set a lambda function in the state machine to ‘wait for callback’, the step will generate a task token in the lambda’s context object, and wait for that task token to be returned. The task token can be returned in a few ways, including webhook listeners, but the simplest way is using the API.

aws stepfunctions send-task-success --task-token YOUR_TASK_TOKEN

When the task token is returned, the state machine resumes - in our case, this would be used to wait for the user to trigger the destroy on the admin app, and then run the CodeBuild build job to destroy the infrastructure.

One of the main benefits we thought Step Functions would have is using Step Functions as the source of truth for the state of the child apps. This would mean we could eliminate a complex flow and reduce the amount of logic in our NextJS app. This was possible in theory, as we could use the AWS API to get the state from each step as needed, reducing our need to handle and store it. In practice, however, when we looked into using callbacks and task tokens, we realised we’d need to store the task token, which means we’d still need our DB.

No doubt there is a better architecture for us to use Step Functions for the full child app lifecycle, but that would involve refactoring. Having weighed up the pros and cons, and keeping in mind that we were almost at MVP and ready for our first release, we decided to park the idea of having the full child app lifecycle on Step Functions and focus on a smaller area - a nightly shutdown of the child apps.

The use case for the child apps, for MVP at least, is for interviews, so they will not need to run overnight. There’s an environmental and monetary cost to leaving apps deployed when they aren’t required, so being able to shut them down automatically is a good feature to add.

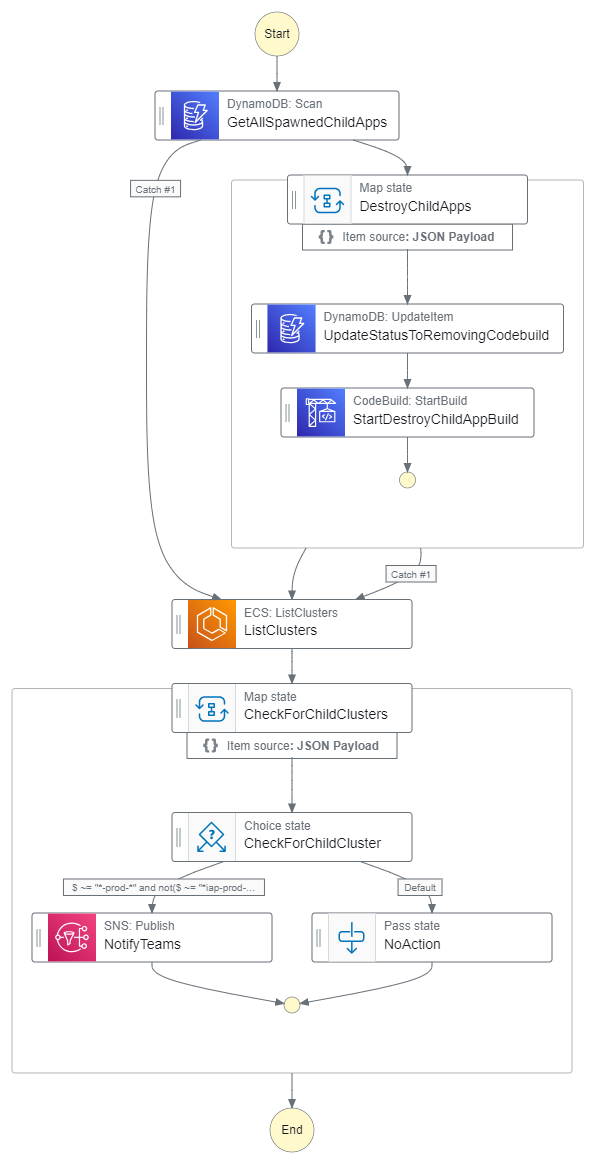

The first design for our nightly shutdown used an ECS:List Clusters step to get the running containers and then shut them down using the CodeBuild build job.

This brings us to the second big issue we found with using Step Functions for our app and infrastructure. For our CodeBuild build job to run, we need to give it a host-name variable, which is used for the ephemeral URL generated for the child app, as well as the names of the AWS resources deployed for that child app. The host names are generated from three words along with the name of the deployed child app, so they can end up being long. As AWS limits the number of characters in names, the host names are truncated when used for the AWS resource names. This posed a problem when we tried to get the host name from the outputs of the ECS step in the state machine - there was no easy way to get the full name needed for the variable, so we’d have to get it from the database.

A redesign brought us to querying DynamoDB to get the host names. This solution has been implemented, and so far, successfully destroying any child apps left up at the end of the working day.

Conclusion

As we have reached MVP and done a release, the team is continuing the investigations into Step Functions and getting the full child-app lifecycle managed by a state machine.

In my opinion, Step Functions is a cool AWS service that is worth spending time looking at. It can do the heavy lifting and make life easier; I’m sure that if the team knew about it earlier, and we had had the benefit of a team that wasn’t constantly changing and making consistent architectural decisions harder, we could have designed our app so that Step Functions and Lambdas do a lot more of the backend work, taking logic out of the NextJS app.

The Internal App Project is an interesting bench project, and I’ve learned a lot!