Knowledge graph technologies certainly appear to be on the rise, and if adoption rates continue to climb these data stores may quickly become something we all need to sit up and take notice of. Indeed, there are already many applications of knowledge graphs out there in domains as diverse as finance, health and social media, all the way to the latest AI and Natural Language Processing techniques.

With no personal experience with them however, I’d always found knowledge graphs (and graph databases) to be a nebulous concept - in short I didn’t really know what they were, but I kind of knew they existed.

In this blog post I’ll give my impressions having looked into these data stores. I’ll go over the basics of what a knowledge graph is, and discuss how and why graph databases can be useful compared to more traditional relational databases. Hopefully this can serve as a useful springboard for anyone else interested in learning the basics.

What is a knowledge graph?

There are a few different definitions around, all of them fairly abstract, but in effect they’re a graphical representation of entities and the relationships between them. They are knowledge that is modelled as a graph of connected entities, hence knowledge graph.

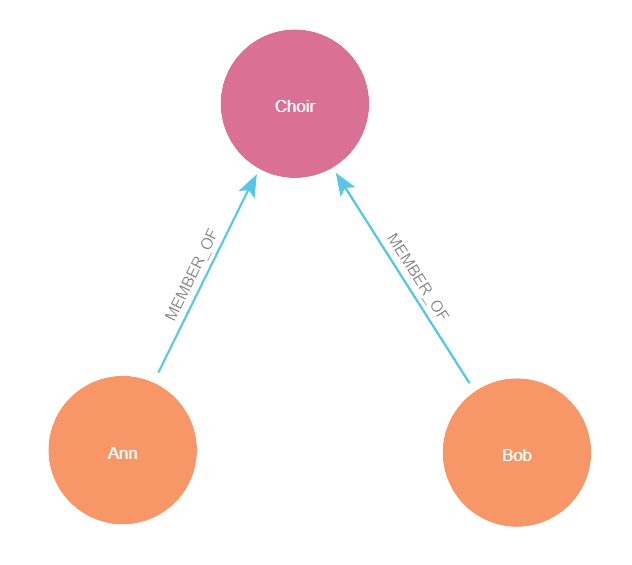

Below is an example of a knowledge graph showing a choir club alongside two of its members - the knowledge it represents is that Ann and Bob are members of a choir.

A simple knowledge graph

Ann, Bob and Choir are entities in the knowledge graph, commonly referred to as nodes.

These nodes can represent anything we can think of, as knowledge graphs are structureless. Here we’re only representing two types of node, members (Ann and Bob) and clubs (Choir), but we could add whatever we like in. If we decided it worthwhile to model the building the choir takes place in, we could add another circle, write ‘village hall’ inside it and we’re away.

The two MEMBER_OF arrows represent the relationships between these entities, commonly referred to as edges.

Here the arrows suggest the relationship has direction; Ann is a member of the Choir, but the Choir is not a member of Ann. In this blog we’ll limit ourselves to relationships that have direction.

So we’ve got a conceptual model of nodes which represent entities, and edges which represent the relationships between those entities. Great!

What is a graph database?

Graph databases are data stores for knowledge graphs. They are databases built on the foundation that the relationships between entities are as important as the entities themselves. By doing so they can put relationships at the forefront of how they are structured, and therefore how they can be queried. As we’ll see later they make traversing relationships in a data store far easier. I have also seen claims that this translates to faster query times when traversing relationships in highly connected data, albeit I haven’t benchmarked this myself.

There are many different graph database vendors around, from Neo4j and TigerGraph, through to Neptune on AWS and Azure’s Cosmos DB. I won’t be doing an in depth analysis on these here, but I think it’s fair to say there’s plenty of choice in the market.

I’m using a Neo4j database throughout this blog alongside their visualisation engine, which lets you view the data as a knowledge graph. Whilst the visualisation engine isn’t necessarily always a part of graph databases (you can store data without one), they are a standard way of interacting with them and viewing the data. Indeed you’ve already seen one, the initial image in this blog post was taken from a Neo4j database.

We’ve got some circles and lines, but where’s the rest of the data?

Knowledge graphs, and by extension graph databases, can include implicit data on both the nodes and the edges.

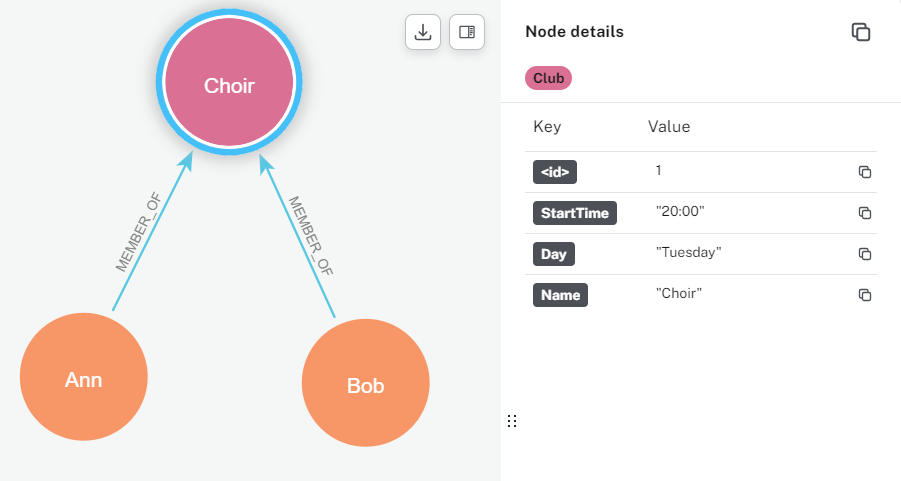

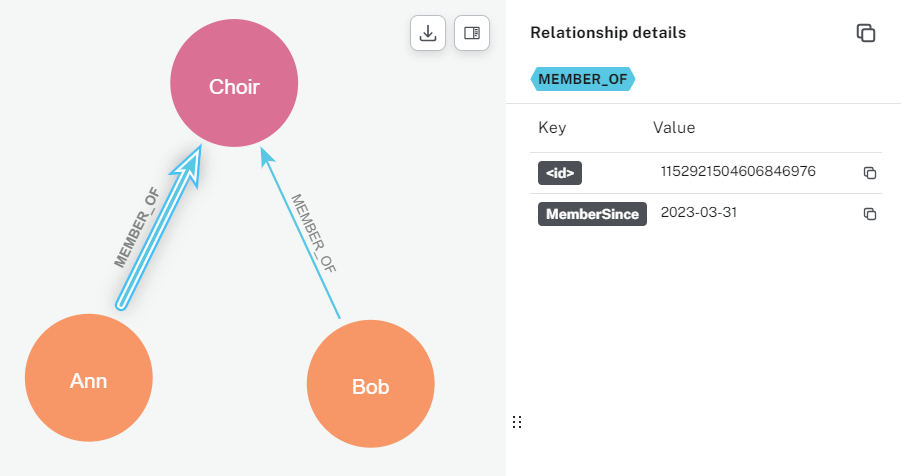

For this example, Neo4j has the concept of labels on nodes, and types on edges. Both can then also have additional data properties. Below shows the Choir node with a label ‘Club’ and a property ‘StartTime’. The edge has type ‘MEMBER_OF’ and property ‘MemberSince’.

Label and property on a node

Type and property on an edge

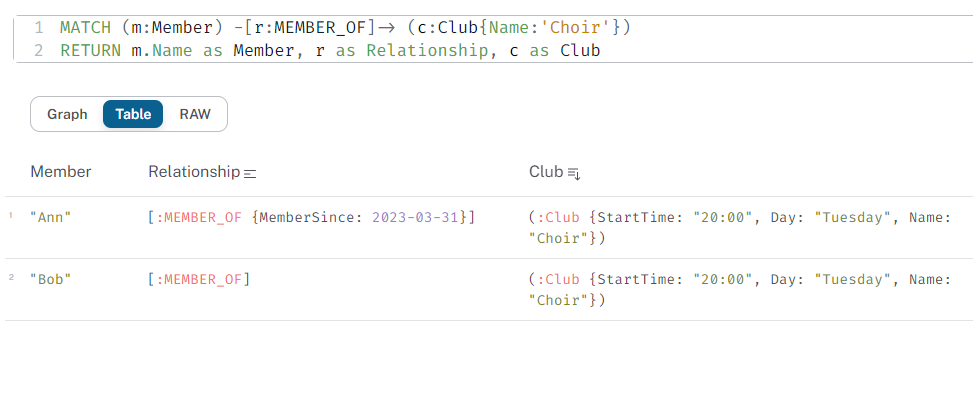

This data is stored directly against these items, and just to show you, you can also retrieve this information in a tabular form as follows:

Properties displayed in a table using Neo4j

A brief Cypher aside

The query at the top is an example of Neo4j’s query language Cypher.

MATCH (m:Member) -[r:MEMBER_OF]-> (c:Club{Name:'Choir'})

RETURN m.Name as Member, r as Relationship, c as Club

I’m not going to go into the details of Cypher in this blogpost, but the above matches any node with the Member label that has a MEMBER_OF relationship to a node with the club label and name property ‘choir’.

It’s a powerful language which is basically the equivalent of SQL in a relational database. Originally created solely for Neo4j it has been open sourced through OpenCypher, a popular querying language for graph databases across multiple vendors.

It’s also worth noting that just recently the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) certified GQL as the official language for graph databases; and Cypher appears to have been a large influence in the creation of this standard.

Why would I use a graph database over a relational database?

I’ll admit this was my first thought, so I knocked up an example of each to allow myself to compare how they act.

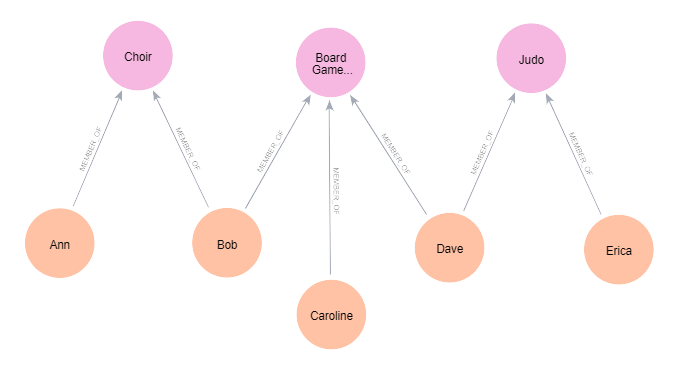

To make things a little more interesting I first expanded out the example from above, adding in some extra clubs and members. We now have 3 clubs: Choir, Board Game club, and Judo. We’ve also got some extra members in those clubs.

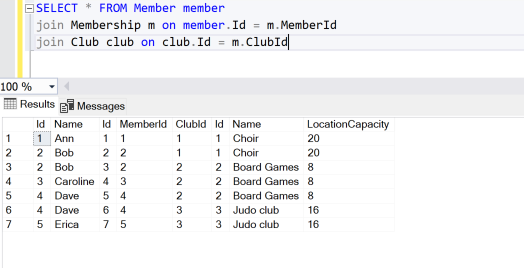

For the purposes of comparison I then created three database tables in Sql to hold the same data. Those tables were Club, Member and Membership, where the Membership table holds the many-to-many relationship between clubs and members.

Knowledge graph representation of members and clubs

Tabular representation of members and clubs

Both of these representations are pretty easy to read, but traversing the relationships of the tabular representation feels clunky in comparison.

For example, what if we wanted to know which members go to a club with Bob?

I find that in the knowledge graph I can link through the relationships easily to traverse the data, whereas in the table form I need to keep track of the data in my head as I read it.

That may sound obvious, but I think it’s a powerful representation of what knowledge graphs and graph databases are for; they are for when the relationships between data are as interesting or important as the data itself. To put it another way, if you have a connected dataset where you’ll be traversing relationships often, they could be the way to go.

Now you might argue that it’s perhaps an unfair comparison, as there is nothing stopping anyone from building a tool to sit above SQL tables to show them in a similar graphical format. The point is that graph databases are built in a way that makes the creation of this visual knowledge graph far easier. Whichever vendor we pick, we can expect there to be nice tools to do this out of the box. So rather than wrangling SQL to try and be something it’s not, we can just use a graph database.

But that’s just a visual, now let’s compare how we might query this data. We’ll construct a Cypher query for the graph database, and a SQL query for the relational database. Let’s assume that Bob wants to throw a party with all of his friends from the clubs he goes to; we want the list of all people who go to a club with Bob. We don’t want to retrieve Erica, as Bob doesn’t go to Judo and doesn’t know her. For the sake of the query let’s also assume he’s always changing clubs, so we don’t have a way of knowing what clubs he goes to ahead of time.

With the SQL tables one such SQL query could look like this:

select mem.Name as PotentialGuests

from Member mem

join Membership mship on mem.Id = mship.MemberId

join Club club on club.Id = mship.ClubId

where club.Id in

(select ClubId

from Membership mship

join Member mem on mem.Id = mship.MemberId

where mem.Name = 'Bob')

and mem.Name <> 'Bob'

Whereas the Cypher query?

MATCH (m:Member) -[r:MEMBER_OF]-> (c:Club) <-[]- (bob:Member{Name:'Bob'})

RETURN m.Name as `PotentialGuests`

They both return the same thing, a table named PotentialGuests with the three members Ann, Caroline and Dave.

Even if you don’t fully follow either of these queries Cypher is clearly the more efficient language in this example. By making relationships a first class citizen of both the data and the language I can more easily query how the different relationships play out.

Even as someone new to it, it was far easier to query nodes and traverse through relationships in Cypher than SQL.

They’re schemaless?

It’s worth mentioning that as graph databases are schemaless they are inherently more extensible than SQL.

If we wanted to add on a new type of Instructor node in our graph database it would be a simple matter of adding an Instructor node, and joining it to our Judo Node with a new type of ‘Instructs’ relationship. In our relational database we’d need to create a new table for our Instructor to live in, then potentially create a new many-to-many table to handle the relationship, so it would be a more involved job. Alternatively maybe we want to refactor the Member database into a People database, who knows? In order to ensure we don’t end up making silly decisions it becomes useful to know our domain space up front, which often isn’t a given in the real world.

The graph database lets us expand out our data in any direction we like, as it isn’t constrained by schema definitions.

Depending on your use case this can be a very beneficial advantage. If you’re building up a database of relationships from natural language processing for example, it can be very useful to be able to store data in a non-normalised manner to allow your data to grow organically as different entities and relationships present themselves.

This can also have a drawback of course; if your data grows organically to a large scale it might become harder to traverse in a meaningful way - without the rigid boundaries such as the table definitions in SQL you might find yourself in a soup of similarly connected nodes connected by almost-but-not-quite-the-same edges.

It’s worth saying that there are tools out there to apply boundaries to graph databases if you need to. As with any schemaless data store just because the technology allows us to grow our data unfettered by any rules, it doesn’t neccesarily mean that we always should. Obviously there are cases where you don’t want to constrain your data, but it’s worth thinking about.

Any other points?

The equivalents of an Object Relational Mapper (ORM) seem to be a bit thin on the ground, and likely vendor and query language dependent. For example coming from a .Net background I’m used to using Entity Framework as an ORM to provide some protection from threats such as SQL injection attacks. Whilst some support is there for graph databases they don’t necessarily give you everything, so you’ll need to be sure you’re not opening yourself to any injection attacks in whichever query language you’re using.

In addition, just to mention, graph databases are for the most part ACID compliant. You’ll want to double check the documentation for the vendor you’re interested in, but it’s certainly a valid requirement and one that many graph databases can handle.

Conclusion

This has been a fairly brief rundown of knowledge graphs and graph databases.

Of course even ignoring SQL there are a multitude of database technologies vying for our attention, from document and key-value stores through to vector databases. Only time will tell how widely adopted knowledge graphs and graph databases will become, but they could be worthy of a look depending on your needs.

Whilst they’re not a magic bullet, with knowledge of the domain space and how the data has been mapped into the graph they can be a powerful tool to help investigate and curate data, allowing you to extract meaningful business insights that might otherwise have been overlooked.

If nothing else, when someone asks you what a knowledge graph is you’ll be able to tell them - they’re just circles and lines*.

*Conditions apply 🙂

Happy graphing all!