Self-Organizing Teams

One of the principles behind the Manifesto for Agile Software Development is:

“The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.”

It’s a simple statement but it hides a big idea. The first and maybe most obvious question is, “What is a self-organizing team?” The Scrum guide has this to say:

“Self-organizing teams choose how best to accomplish their work, rather than being directed by others outside the team.”

Again, very simple but quite powerful.

It’s easy to misinterpret this I think and a criticism I’ve heard levelled at agile development a few times is that it is anti-management. Indeed, it’s easy to see how, taken at face value, those two statements combined could lead you to the conclusion that agile teams should get rid of leaders and management. I don’t believe that’s either true or the intent. Teams need leaders and removing leadership entirely is never a good idea. Most projects, especially larger ones, also need management in some form or another. It’s important to recognise that management isn’t the same as leadership: a leader can be anyone, they are defined by what they do rather than their job title. A manager on the other hand is specifically hired for the role. That’s not to say managers can’t also be great leaders and often they are.

If we’re not talking about embracing anarchy and removing all leadership and management then, what are self-organizing teams all about?

Ways we can direct tasks

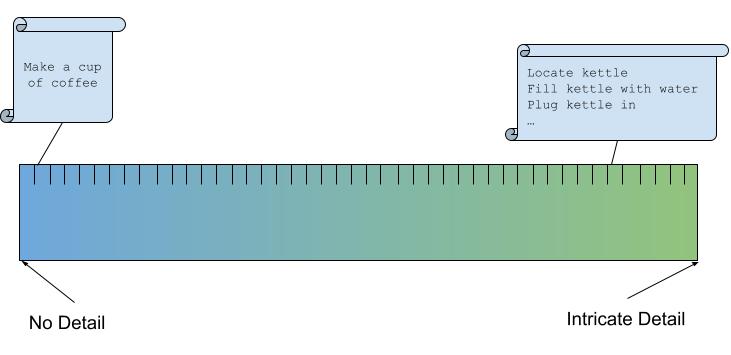

Let’s think for a minute about how we perform tasks. Any given task can be directed on a scale going from no instructions at all right up to specifying the steps in intricate detail. The appropriate level of detail to give depends on the task and is not always easy to decide. For example I could ask you to make a cup of coffee in multiple different ways from “Can you make me a coffee please?” right up to a detailed list of all the steps required to do that and everything in-between, such as “milk no sugar”.

I have a military background and many tasks in the military are directed at the more detailed end of this spectrum. For example, when firing a rifle on the range the list of steps is clearly and strictly set out as a series of drills which must be memorised and performed exactly. This has the benefit of removing ambiguity from the process. If a mistake is made then there is no argument around what the correct process should have been, either the drill was followed correctly or it was not. On a rifle range this increases control and reduces the chances of something unexpected happening thus increasing safety. What this approach does not allow for is creativity which is arguably a good thing in that particular context.

I’m also a big fan of Jazz as a musical genre. The central idea common to all types of Jazz music from New Orleans to Fusion is that of improvisation. As a very generalised example, a Jazz band may play a piece of music through as written (or straight) once or twice and then members of the group will take turns in improvising over the piece before ending with another straight play through. This, in my opinion is what makes Jazz so interesting, the freedom to improvise can facilitate some truly great music that may not have happened otherwise and means that you can hear the same band play the same piece many times and always get something new. This is very much towards the other end of the detail spectrum, the piece of music providing the high level rules for the task and the band making up the rest. In fact in Free jazz we go even further and throw the rule book out almost entirely!

How we create software and does it matter?

So what has all this go to do with software development? The concept of self-organizing teams moves the pointer away from the granular end of how we can direct tasks and instead the team improvises its own process within the rules provided. An agile team for example may take the Manifesto for Agile Software Development as a starting point and build out their own process within that boundary and maybe others set out by management.

The question then is, why do we care about how much freedom we have to improvise and create process for ourselves? It certainly sounds a lot easier to let someone else define the way we work and then just do that. After all, we didn’t become software engineers, testers, UX designers etc. to sit around worrying about process. Add to that it sounds safer: if there are a strict set of instructions we know exactly what we’re doing and if it all goes wrong then, as long as we did the drill correctly, the blame can’t be laid on us. Sounds much nicer to just be left to get on with the coding, testing, designing work, right? The answer I think is very simple. We should care, and care passionately and I’ll tell you why.

The Toyota way 1

One reason we should care of course is because we’re the people who are going to have to work with these processes every day. That’s a great reason, but it’s not the only reason. It turns out, from a business perspective it’s important that the people doing the work care about, and have a say in how that work is done as well.

In the early 1980’s the General Motors factory in Fremont California was notoriously one of the worst in the country. Workers were regularly late or didn’t turn up at all and cars were riddled with defects. The plant was eventually shut down but was reopened when GM later decided to partner with Toyota who were looking to break into the American market. Toyota took over using Lean manufacturing techniques and quickly transformed the factory to having one of the lowest defect rates in the country with absenteeism falling from 20% to 2% using the same labour force. One of the secrets behind this transformation was in putting trust in the workforce and giving them control over their own processes. Rather than tell workers the best way to do their job, workers were given control over their own processes to the extent of even being able to stop production entirely if they encountered a problem. Toyota understood that the people best equipped to decided the optimal way to do a job are those who do the job every day. This seems logical when you step back and look at it.

If we want to find the best way to develop software, then we have to ask the people developing the software. We need to make sure the development team are directly involved in defining the process which they are going to use every day and that the process can be easily and quickly changed without friction or blockers from above.

Control -> Ownership -> Engagement -> Interest -> Fun

Let’s reflect for a moment on that high absenteeism in the GM factory. It seems a safe bet that the workers there did not enjoy their work. When teams have control over process, if people are unhappy with the process they make a change and things improve; if the ability to change the processes is restricted people either remain unhappy or worst case will leave the team entirely.

Back in the Air Force, we occasionally had military exercises where everyone would go and live in a field and pretend to be at war essentially. During these exercises various scenarios would be acted out, both official and ad hoc, to simulate the real events. One rainy evening we were all pulled from our warm sleeping bags and lined up in front of the station Warrant Officer for a collective tongue-lashing. This issue preoccupying the Warrant’s mind it seemed was this: A drill had been organised to simulate a fire on camp, this had been achieved by lobbing a smoke grenade into the Padre’s tent (presumably notifying the padre in advance). The officers organizing this drill had then stood back and waited for the troops to spring into action. To their dismay what they observed was that, as the smoke bloomed out of the tent, rather than run towards the smoke and sound the alarm, service personnel, on sighting the smoke either did nothing or quickly turned around and walked in the opposite direction. In fact, one Airman walking past the tent was overheard to observe to his mate “Padre’s having a good time!”. Needless to say the Station Warrant Officer did not see the humour in the situation.

While this is an amusing story, it illustrates an important point. The personnel in the story had by that time been on exercise for over a week and they were cold, wet and tired. The drills happened at least a few times a day and those participating were expected to respond correctly first time or else receive a dressing down from the officers in charge. By the time of the incident in question, people had lost any enthusiasm they may have had for participating. No one walking towards the tent that evening after a long day wanted to get dragged into yet another drill which would not only take up most of their evening but also put them in the firing line if they didn’t get the drill correct. This resulted in people either avoiding the obvious problem or else pretending they hadn’t seen it.

People who are not enjoying what they do or feel that they are not safe to make mistakes are not motivated to run towards the smoke. In software this translates to scenarios such as developers seeing issues and not raising them. They may be worried about getting the blame or maybe they just don’t care enough to get sucked into trying to fix the issue. It’s far easier to pretend you haven’t seen it and hope someone else picks it up. An important realisation is that no amount of top down enforcement of rules will address this problem, change will only happen when people start to care about the project.

Giving teams control fosters a sense of ownership, ownership creates engagement, engagement leads to interest and if something is interesting, then it’s fun!

Software development teams

Let’s take a pause here and consider how all this applies to developing software. It’s important to state upfront that there is no “correct” answer to how much freedom teams need to thrive. Clearly, the intricate detail end of the scale will likely cause issues for most teams and restrict a teams ability to fully define their own process. On the other hand providing no instruction at all, or very little is often not helpful either. A company, for example, may mandate that teams must all be practising Scrum: this might seem logical at first as all teams are doing the same thing while still having some flexibility within that framework. In practice however it may be that some Scrum practices do not work well for certain teams and restricting teams from changing those practices, simply because it doesn’t fit the provided framework, may very well prevent teams from finding the process which works best for them. It’ worth noting that all teams need a starting point and suggesting that teams use a certain framework to get started is most likely useful, the key here is to allow teams to then evolve those processes as they go forward and not restrict that process unnecessarily.

Conclusion

Why should you care about process? Well first up, because you’re most likely the one who has to follow that process! Software development should be both fun and engaging for the creative and intelligent development teams who do the job, this is beneficial from an individual perspective but also benefits the project and team as a whole as we saw in the Fremont case study. Moreover, development teams are best placed to say how development should be done and when they have control over process as a self-organizing team, they not only can guide creating the best processes but also gain a sense of ownership which often translates to pride in the product being created. If we are happy with the processes we are working under and feel we have control we are more likely to give our best effort, we are more likely to run towards the smoke than to turn around and go the other way.

-

For more information on the Toyota story see Lessons on culture change at Toyota and How GM learned from the Toyota way at Fremont. ↩