If you’ve worked in software for more than 5 minutes, then you’ve probably heard of cloud computing. And if you’ve worked in cloud computing for more than 5 minutes, you’ve probably heard of either Terraform or AWS CDK (also known as CDK).

Both Terraform and CDK are tools for implementing infrastructure as code (IaC) which speed up cloud development by allowing a user to code their cloud resources before deploying them.

This allows the cloud architecture to be treated as code, that is, replicated, reviewed and stored just like any other code. It also means that we can deploy or destroy a complex mesh of cloud resources with just one command; saving a lot of time, effort, money and mistakes.

Using IaC for cloud deployment has become an industry standard thanks to its security properties.

If you want a record of all resources deployed (without having to search through cloudtrail logs), who deployed them and when, and allow the ability to review the resources in code before deploying, you can create a role with deployment permissions, and allow only a CI/CD runner to have that role. This means that a person cannot physically deploy without first having their resources reviewed, scrutinised, approved, and their deployment recorded by the CI/CD job.

As a developer with 2 and a half years experience with cloud computing and over 2 years of experience with Terraform, I’ve recently finished an upskilling project learning CDK.

In this blog, I’ll cover some of the differences between the two and which one you might prefer to use. To explain their differences, it’s easier to start with explaining how they work…

Terraform workings

Terraform works with something called the ‘Terraform state’ , a JSON file (stored either locally or within the cloud) which acts as a record for all the resources that Terraform has deployed to the cloud.

When deploying, Terraform will write to the state, and when deleting, it will remove from the state. This enables Terraform to know what to delete and which resources to change/replace when alterations are deployed.

The Terraform state leads to some of the major common issues people run into when using Terraform.

If anything is not deployed with Terraform, but is changed manually, it is not recorded on the Terraform state and can lead to errors when re-deploying.

As the Terraform state isn’t directly tied to AWS, and Terraform itself is cloud agnostic, it can be used on any major cloud platform.

CDK workings

CDK on the other hand, is fully integrated into AWS, and uses CloudFormation to deploy its stacks.

When you deploy CDK code, it will compile the stack into a CloudFormation template, a machine-readable list of resources in either YAML or JSON format.

After this, the template is then deployed and can be viewed under CloudFormation in the AWS Console.

While this eliminates the problems which come with the Terraform state, any issues that you have with a CloudFormation deployment will be inherited by CDK, such as stack drift (the same error we get with Terraform where the stack has changed significantly from its template) or stack resource limits (although at 500 resources, the limit is arguably big enough for a well-coded stack).

Getting to grips with Terraform

Terraform is written in hashicorp language (HCL), which reads similar to JSON. Personally I find it quite easy to read, however at first it took some time to get to grips with. Particularly on how to write variables, and writing/ using modules.

resource "aws_instance" "example_instance" {

instance_type = "t2.micro"

ami = var.ami_name

}

One particular issue with Terraform (which I guarantee you will come across on any multi-env Terraform project) is almost embarrassing in its solution.

There are occasions where you’d want to create a resource only when you’re in a certain environment; like an IAM policy allowing user permissions or a bastion host which you want on a dev environment, and not a prod one. The way to go around this with Terraform is to use the ‘count’ meta-argument. ‘count’ allows you to specify how many instances of a resource you’d like to create, and can be thought of as a loop.

An example of using ‘count’ to deploy 3 separate EC2 instances is shown below:

resource "aws_instance" "example_instance" {

count = 3

instance_type = "t2.micro"

ami = var.ami_name

tags = {

Name = "instance ${count.index}"

}

}

Its original intended use was for creating many resources with the same configuration (as seen above), but it’s mainly used as a ‘create one of these only in this environment’ argument.

For example, creating an instance only in a Dev environment:

variable "environment" {

type = string

description = "Environment where resources are deployed"

validation {

condition = contains(["Dev", "Prod"], var.environment)

error_message = "The environment must be either 'Dev' or 'Prod'"

}

}

resource "aws_instance" "only_exists_in_dev" {

count = var.environment == "Prod" ? 0 : 1

instance_type = "t2.micro"

ami = var.ami_name

tags = {

Envrionment = var.environment

}

}

In fact, I’ve personally never seen it be used to create more than one resource.

It seems like there should be an easier way of alternating resources with each environment, as using different environments is so common in cloud computing that it’s almost laughable that there isn’t an integrated environment argument for resource creation.

It’s ironic that this is predominantly the main use for ‘count’ and most users hate it, yet in its 8 years as open source, no one came up with a better solution.

However, I will admit that the well written documentation, and the sheer number of examples you can find online makes learning and solving problems in Terraform a lot easier than they could be.

Another thing I find useful with Terraform is that it appears asynchronous, meaning that any resource can be referred to in any other Terraform file. Order does not matter. I can create an EC2 which references a VPC further down the file and have no issues. This comes in quite useful in cloud computing with the amount of interlinked dependencies and will still allow for tidy, organised codebase.

It’s important to note that Terraform isn’t actually asynchronous, it takes what is given to it, and creates a dependency chain upon compiling; hence some cyclic dependencies such as security groups require separating.

resource "aws_security_group" "A" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

egress {

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

security_groups = [aws_security_group.B.id]

}

}

resource "aws_security_group" "B" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

egress {

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}

resource "aws_security_group_rule" "Traffic from A to B" {

type = "ingress"

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

security_group_id = aws_security_group.A.id

source_security_group_id = aws_security_group.B.id

}

For example, we can reference Security Group B from Security Group A with no issue, but we can’t directly reference Security Group A from Security Group B (as this would create a cyclic dependency).

So the chain of dependency upon deployment is Security group B, then Security Group A (reliant on B), and then adding the rule referencing A to B (reliant on both A and B).

When working with Terraform you have to write out every single resource you declare, you can however put it behind a layer of abstraction by using Terraform modules. If you’re familiar with CDK, Terraform modules are the Terraform equivalent of Constructs. You can create and declare them locally, or you can use modules provided on the Terraform registry from both official providers and community contributors.

However if you want an architecture which is incredibly tight security-wise, it’s common practice to resort to only using locally defined modules, so that the code is explicit with every single resource created.

Getting to grips with CDK

If you have any experience with TypeScript, JavaScript, Python, Java, C# or Go, then you can already code CDK. There is no new language to learn, you can integrate it entirely into your codebase.

As there’s no need to learn an entire language before you can start to write up resources, this leads to a quicker initial learning curve. I noticed this on my upskilling project: Devs who had never touched AWS or Terraform picked up on CDK quicker than people tend to do with Terraform. In part because there were fewer barriers with language, layout and syntax.

Another property speeding up the learning curve is that CDK can ‘fill in the gaps’ of cloud computing.

A great example is the automatic creation of subnets (public and private), NAT Gateways, an Internet Gateway, route tables and ready-configured security groups AS WELL AS the creation of our EC2 instance, AMI and VPC, all done within the creation of a single instance, as shown below:

new ec2.Instance(this, "instance", {

vpc: new Vpc(this, id),

instanceType: ec2.InstanceType.of(

ec2.InstanceClass.T2,

ec2.InstanceSize.MICRO

),

machineImage: new ec2.AmazonLinuxImage({

generation: ec2.AmazonLinuxGeneration.AMAZON_LINUX_2,

}),

});

When using standard L2 Constructs in CDK, the CDK compiler will fill in gaps as shown above, and (most usefully) will analyse which resources are connected to which, and will create route tables and security groups and even configure them for you based on those connections. While you may have to add a connection or correct a security group if CDK does miss out a connection, in most cases CDK has it covered.

CDK’s resource abstraction dramatically cuts down on the lines of code needed to deploy resources, as well as reducing the time taken working on connecting resources up.

To demonstrate this, I’ll show the following architecture on both Terraform and CDK:

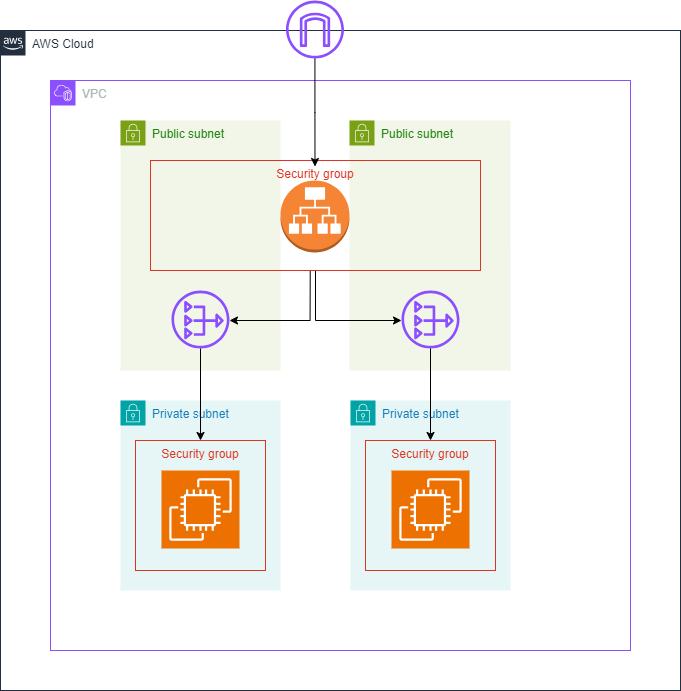

An Internet Gateway, connected to an Application Load Balancer (ALB) inside a VPC in a subnet group consisting of two Public subnets. This is routed to two NAT Gateways (one per Public subnet), which each point to an EC2 in their corresponding Private subnets.

Both the EC2s and ALB have Security Groups controlling traffic in/out.

Bearing in mind that both of these examples are using their out-of-the-box libraries (no 3rd party modules or constructs), here’s the architecture coded both ways.

Terraform - 178 lines

resource "aws_vpc" "example_vpc" {

cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/24"

}

resource "aws_subnet" "public_subnet_a" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/26"

availability_zone = "eu-west-2a"

}

resource "aws_subnet" "public_subnet_b" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

cidr_block = "10.0.0.64/26"

availability_zone = "eu-west-2b"

}

resource "aws_subnet" "private_subnet_a" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

cidr_block = "10.0.0.128/26"

availability_zone = "eu-west-2a"

}

resource "aws_subnet" "private_subnet_b" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

cidr_block = "10.0.0.192/26"

availability_zone = "eu-west-2b"

}

resource "aws_internet_gateway" "example_igw" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

}

resource "aws_route_table" "public_subnet_a_routetable" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

gateway_id = aws_internet_gateway.example_igw.id

}

}

resource "aws_route_table_association" "public_a_routetable_association" {

subnet_id = aws_subnet.public_subnet_a.id

route_table_id = aws_route_table.public_subnet_a_routetable.id

}

resource "aws_route_table" "public_subnet_b_routetable" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

gateway_id = aws_internet_gateway.example_igw.id

}

}

resource "aws_route_table_association" "public_b_routetable_association" {

subnet_id = aws_subnet.public_subnet_b.id

route_table_id = aws_route_table.public_subnet_b_routetable.id

}

resource "aws_route_table" "private_subnet_a_routetable" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

nat_gateway_id = aws_nat_gateway.natgw_a.id

}

}

resource "aws_route_table_association" "private_subnet_a_routetable_association" {

subnet_id = aws_subnet.private_subnet_a.id

route_table_id = aws_route_table.private_subnet_a_routetable.id

}

resource "aws_route_table" "private_subnet_b_routetable" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

nat_gateway_id = aws_nat_gateway.natgw_b.id

}

}

resource "aws_route_table_association" "private_subnet_b_routetable_association" {

subnet_id = aws_subnet.private_subnet_b.id

route_table_id = aws_route_table.private_subnet_b_routetable.id

}

resource "aws_security_group" "alb_sg" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

ingress {

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

egress {

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

security_groups = [aws_security_group.ec2_sg.id]

}

}

resource "aws_security_group" "ec2_sg" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

ingress {

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

security_groups = [aws_security_group.alb_sg]

}

}

resource "aws_eip" "eip_a" {

vpc = true

}

resource "aws_eip" "eip_b" {

vpc = true

}

resource "aws_nat_gateway" "natgw_a" {

allocation_id = aws_eip.eip_a.id

subnet_id = aws_subnet.public_subnet_a.id

}

resource "aws_nat_gateway" "natgw_b" {

allocation_id = aws_eip.eip_b.id

subnet_id = aws_subnet.public_subnet_b.id

}

resource "aws_instance" "instance_a" {

ami = "ami-f976839e"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

subnet_id = aws_subnet.private_subnet_a.id

vpc_security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.ec2_sg.id]

}

resource "aws_instance" "instance_b" {

ami = "ami-f976839e"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

subnet_id = aws_subnet.private_subnet_b.id

vpc_security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.ec2_sg.id]

}

resource "aws_lb" "example_alb" {

internal = false

load_balancer_type = "application"

subnets = [aws_subnet.public_subnet_a.id, aws_subnet.public_subnet_b.id]

security_groups = [aws_security_group.alb_sg.id]

}

resource "aws_lb_target_group" "example_target_group" {

port = 80

protocol = "HTTP"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example_vpc.id

}

resource "aws_lb_target_group_attachment" "target_group_attachment_a" {

target_group_arn = aws_lb_target_group.example_target_group.arn

target_id = aws_instance.instance_a.id

port = 80

}

resource "aws_lb_target_group_attachment" "target_group_attachment_b" {

target_group_arn = aws_lb_target_group.example_target_group.arn

target_id = aws_instance.instance_b.id

port = 80

}

resource "aws_lb_listener" "example_alb_listener" {

load_balancer_arn = aws_lb.example_alb.arn

port = 80

protocol = "HTTP"

default_action {

type = "forward"

target_group_arn = aws_lb_target_group.example_target_group.arn

}

}

CDK - 58 lines

const vpc = new Vpc(this, id);

const instanceSG = new ec2.SecurityGroup(this, "instanceSG", {

vpc,

allowAllOutbound: false,

});

const instance1 = new ec2.Instance(this, "instance1", {

vpc,

instanceType: ec2.InstanceType.of(

ec2.InstanceClass.T2,

ec2.InstanceSize.MICRO

),

machineImage: new ec2.AmazonLinuxImage({

generation: ec2.AmazonLinuxGeneration.AMAZON_LINUX_2,

}),

securityGroup: instanceSG,

});

const instance2 = new ec2.Instance(this, "instance2", {

vpc,

instanceType: ec2.InstanceType.of(

ec2.InstanceClass.T2,

ec2.InstanceSize.MICRO

),

machineImage: new ec2.AmazonLinuxImage({

generation: ec2.AmazonLinuxGeneration.AMAZON_LINUX_2,

}),

securityGroup: instanceSG,

});

const albSecurityGroup = new ec2.SecurityGroup(this, "albSG", {

vpc,

allowAllOutbound: false,

});

albSecurityGroup.addIngressRule(ec2.Peer.anyIpv4(), ec2.Port.tcp(80));

albSecurityGroup.addEgressRule(instanceSG, ec2.Port.tcp(80));

instanceSG.addIngressRule(albSecurityGroup, ec2.Port.tcp(80));

const alb = new elb.ApplicationLoadBalancer(this, "alb", {

vpc,

internetFacing: true,

securityGroup: albSecurityGroup,

});

const listener = alb.addListener("listener", { port: 80, open: false });

listener.addAction("action", {

action: elb.ListenerAction.forward([

new elb.ApplicationTargetGroup(this, "TargetGroup", {

vpc,

targetType: elb.TargetType.INSTANCE,

port: 80,

targets: [

new elb_target.InstanceTarget(instance1),

new elb_target.InstanceTarget(instance2),

],

}),

]),

});

While you can argue that some of the line number difference could be down to the standard formatting I’ve used, there’s no argument that CDK undeniably uses fewer characters (1633) than Terraform (4646) I can confirm that the Terraform example took me twice as long to configure than the CDK one.

However this ‘fill in the gaps’ approach with CDK does come with its downsides. By making the resources deployed less explicit within the codebase, you potentially run into issues with budgeting, security, monitoring, and even hitting the max resource quotas without even knowing that you were deploying said resource.

An example of this from my recent upskilling project was hitting the maximum number of ElasticIPs for a region. Each environment had two private and two public subnets, with our EC2 instances in the private subnets connected to the ALB in the public subnets. As mentioned, CDK helpfully created two NAT Gateways (one per public subnet) per environment, which also requires an ElasticIP per NAT Gateway.

When attempting to deploy a 3rd environment, we hit the max number of ElasticIPs in the region (5) without even realising that we were deploying any. If you’re reading carefully, you’ll notice that the architecture is very similar to the one above used for our comparison, and be able to spot where Terraform creates the NAT Gateways and ElasticIPs, but not CDK…

It’s also worth mentioning that there is a way to code with CDK which avoids creating resources which aren’t explicitly specified: L1 constructs, which are essentially basic CloudFormation resources, translated into an easy to use coding language.

The majority of our use of CDK on project was with L2 constructs (shown in the examples), which have this abstraction built in. There is an alternative option of L3 constructs, which abstract away resource creation even further, to the stage of creating complete application architectures.

Much like the Terraform Registry, there is also the CDK construct hub for community-written constructs. However from opinions I’ve heard so far, the Terraform module registry is much more favoured than the construct hub.

The main difficulty I had with learning CDK was the lack of examples online. It has only been around since 2019, whereas Terraform was launched in 2014, meaning that the CDK documentation isn’t quite as clear, there are fewer code examples, and still has the odd bug (the one we came across required cancelling and rerunning cdk deploy if using addAsgCapacityProvider).

It would also be a crime on my part to forget to mention that CDK allows you to directly integrate your cloud infrastructure into object oriented code, whereas Terraform has to be in separated files in a different language to the rest of your code. While this can be incredibly useful for someone more used to object-oriented coding, the majority of my uses for CDK was limited to just resources, so I didn’t get an opportunity to give this an honest go.

That being said, I’ve definitely saved some time with CDK and found that other developers new to the cloud have picked it up well.

So….. Which one’s “better”?

Well like with most tech… it depends…. Personally I’d lean towards Terraform, however that could be more to do with my familiarity with the tech, the explicitness which comes with the lack of abstraction, and my love of high quality documentation and (somewhat) asynchronous development.

If you want a cloud agnostic IaC, and want to be explicit in all your resources you’re deploying, then Terraform is the go to choice. However, if you’re already familiar with other coding languages, would like to integrate your cloud architecture with your codebase further than you can with Terraform, want to specialise in AWS and (understandably) hate updating route tables and security groups, then CDK is the way forward.

As an amateur cloud architect, I’m glad to have had some practical experience with both, but I would rather stick with Terraform in future endeavors.

Although Terraform has been an industry standard for years now, it has recently had a change of license, and of 10th August 2023, is no longer open source, so it’ll be interesting to see the trends and popularity of different cloud IaC technologies, whether Terraform will keep the title of industry standard, or whether it will be overtaken by AWS CDK, CDK for Terraform (a recent new contender from hashicorp since 2022), or even openTofu, a new, opensource IaC which was forked off an older version of Terraform, now maintained by the linux foundation.