Introduction

In the Java ecosystem, dealing with null values has always been a source of confusion and bugs. A null value can represent various states: the absence of a value, an uninitialized object, or even an error. However, there has never been a consistent, standardized approach for annotating and ensuring null-safety at the language level.

Nullability annotations like @Nullable and @NonNull are often used, but they’re not part of the core Java language, leading to inconsistencies across libraries and frameworks. Some use the defunct JSR-305 @Nullable from the javax.annotation package, while others prefer @NotNull from org.jetbrains.annotations. However, these solutions are often inconsistent and can lead to confusion or errors in codebases.

JSpecify is a specification that provides a standardized approach to annotating nullability in Java, offering a set of annotations designed to improve code clarity and prevent null-related bugs. The goal is to eventually make these annotations part of the standard Java platform.

The Four Nullness Annotations

JSpecify introduces four key annotations to express nullness:

@Nullable: Indicates that a variable, parameter, or return value can be null.@NonNull: Indicates that a variable, parameter, or return value cannot be null.@NullMarked: Marks a package or class that you’re annotating to indicate that the remaining unannotated type usages are not nullable. This reduces the noise from annotation verbosity.@NullUnmarked: Explicitly marks a package or class as not using JSpecify’s nullness annotations as the default. This is used for exceptions to@NullMarkedpackages.

The goal is to allow for more predictable null handling, minimizing the need for runtime null checks and making nullness explicitly part of the contract of methods and fields.

This post covers the process of setting up JSpecify 1.0 in your project, configuring IntelliJ IDEA and Gradle, and how to effectively use the four core annotations: @Nullable, @NonNull, @NullMarked, and @NullUnmarked.

Applying JSpecify Incrementally to a Legacy Project

Let’s imagine a very simplistic User class:

public class User {

private String name;

private String address;

public User(String name) {

if (name == null) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Name cannot be null");

}

this.name = name;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public String getAddress() {

return address; // Could be null

}

public void setAddress(String address) {

this.address = address;

}

public String getFormattedAddress() {

return getAddress().toUpperCase(); // Potential NPE!

}

}

This User class has a glaringly obvious NullPointerException in getFormattedAddress(). Let’s use JSpecify to address this.

Step 1: Add JSpecify Dependency

To integrate JSpecify into a Gradle project, add the JSpecify annotation library as a dependency. As of version 1.0, JSpecify is available in Maven Central, so it’s straightforward to include.

In your build.gradle (or build.gradle.kts), add the following dependency:

First, in your build.gradle (or build.gradle.kts) add the JSpecify dependency to your project (using Gradle):

dependencies {

implementation 'org.jspecify:jspecify:1.0.0'

}

Step 2: Introduce @Nullable and @NonNull

We can start by annotating the getAddress() method:

import org.jspecify.nullness.Nullable;

import org.jspecify.nullness.NonNull;

public class User {

public User(String name) {

if (name == null) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Name cannot be null");

}

this.name = name;

}

public @Nullable String getAddress() {

return address;

}

public void setAddress(@Nullable String address) {

this.address = address;

}

public @NonNull String getName() { return name; }

public String getFormattedAddress() {

String address = getAddress();

if (address != null) {

return address.toUpperCase();

} else {

return ""; // Or handle null appropriately

}

}

}

Now, a static analysis tool (like IntelliJ’s built-in inspection or Error Prone) will warn us about the potential NPE in getFormattedAddress() if we don’t handle the null case. We’ve added a null check to fix it.

Step 3: Using @NullMarked

To reduce verbosity, especially in larger classes or packages, use @NullMarked:

import org.jspecify.nullness.Nullable;

import org.jspecify.nullness.NullMarked;

@NullMarked

public class User {

private String name; // Treated as @NonNull because of @NullMarked

private @Nullable String address;

// ... other code

}

Now, all unannotated types within the User class are treated as @NonNull, unless explicitly marked with @Nullable.

We can also apply @NullMarked and @NullUnmarked at the Package and Module Levels. If you needed to exempt a class from the null marked package you would use @NullUnmarked on the class you need to exempt.

At the Package Level

You can place @NullMarked or @NullUnmarked in a package-info.java file to affect the entire package.

// package-info.java

@NullMarked

package com.example.myapp;

All classes in the com.example.myapp package will now assume non nullable types by default unless explicitly overridden.

At the Module Level

If your project is modularized, you can also use these annotations at the module level by adding @NullMarked or @NullUnmarked to the module-info.java file.

// module-info.java

@NullMarked

module com.example.myapp {

requires java.base;

// .... other require details

exports com.example.myapp;

}

This will make sure all types within the module are non nullable by default.

Starting at the class level annotations and then moving to package or module annotations provides a way to apply nullness analysis in stages to what may be a large existing project.

IntelliJ Null Analysis

Once JSpecify is included in your project, you need to ensure that IntelliJ IDEA is properly set up to recognize and process these annotations.

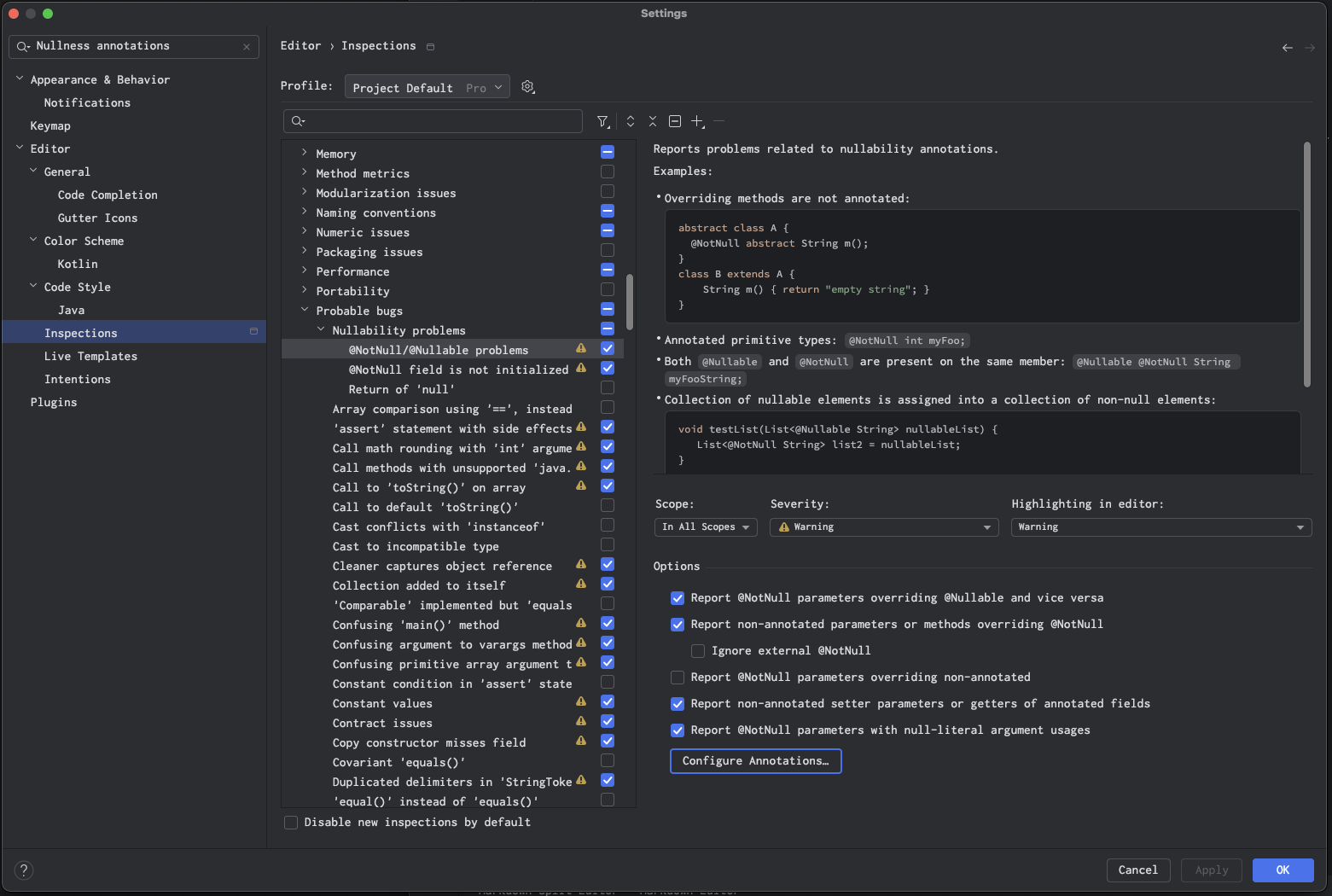

IntelliJ IDEA has built-in support for JSpecify. Enable “Nullness annotations” under Settings/Preferences > Editor > Inspections > Java -> Probable bugs to see warnings about potential NPEs based on your JSpecify annotations.

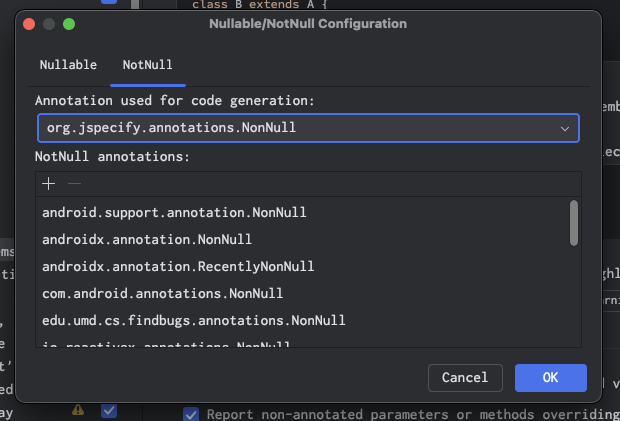

If you want to use jspecify notifications in generated code then you can set that here

If you want to use jspecify notifications in generated code then you can set that here

Implementing detection with Gradle using ErrorProne and Nullaway

Error Prone

Error Prone is a static analysis tool for Java that catches common programming mistakes at compile time. Instead of just producing compiler warnings, Error Prone directly integrates with the Java compiler to generate more informative and precise error messages. It goes beyond simple syntax checking by analyzing the abstract syntax tree (AST) of your code to identify problematic patterns.

What Error Prone Does:

Finds common bugs: Detects a wide range of errors, including null pointer dereferences, incorrect equality checks, misuse of collections, and many more.Provides clear error messages: Offers specific, actionable error messages that explain the problem and often suggest how to fix it.Integrates with the compiler: Works seamlessly with the Java compiler, so you don’t need a separate tool or process.Extensible: Allows you to write custom checks to enforce project-specific coding standards.

Error Prone can be used in many useful ways, even fixing some issues automatically. This will be covered in more depth in a future post.

NullAway

NullAway is a static analysis tool built on top of Error Prone specifically designed to detect null pointer dereferences. It leverages annotations (such as JSpecify’s @Nullable and @NonNull) to understand the nullness constraints of your code and identify potential NPEs.

What NullAway Does:

Focuses on nullness: Specifically targets null pointer dereferences, providing highly accurate null analysis.Annotation-driven: Uses annotations to understand nullability, allowing you to express your intent clearly.Integrates with Error Prone: Builds upon Error Prone’s infrastructure for seamless integration with the Java compiler.Configurable: Offers various options to fine-tune the analysis and handle specific scenarios.

Using Error Prone and NullAway with Gradle

Here’s how to integrate Error Prone and NullAway into your Gradle build:

plugins {

id("net.ltgt.errorprone") version "4.1.0"

id("net.ltgt.nullaway") version "2.1.0"

}

dependencies {

implementation('org.jspecify:jspecify:1.0.0')

errorprone('com.google.errorprone:error_prone_annotations:2.36.0')

annotationProcessor('com.google.errorprone:error_prone_core:2.36.0')

}

tasks.withType(JavaCompile).configureEach {

options.errorprone.nullaway {

error()

// This will default this package to @NullMarked

// If you don't want any specifically marked then need to pass empty string

annotatedPackages.add("your.basepackage")

}

// Include to disable NullAway on test code

if (name.toLowerCase().contains("test")) {

options.errorprone {

disable("NullAway")

}

}

// Optional: configure Error Prone to fail the build on errors

options.errorprone.allErrorsAsWarnings.set(true)

options.errorprone.disableWarningsInGeneratedCode.set(true)

options.errorprone.errorproneArgs.addAll(

"-Xep:NullAway:WARN", // Enable NullAway with WARN severity

"-Xep:CheckReturnValue:WARN", // Example of another Error Prone check

"-Xep:UnusedVariable:WARN",

"-Xep:UnusedMethod:WARN",

"-Xep:EqualsHashCode:WARN",

"-Xlint:-processing" // Suppress annotation processing warnings

)

}

This configures Error Prone (with NullAway) to run during compilation, providing more robust null analysis that could be enhanced to be used with a gradle profile as part of automated CI builds.

JSpecify with Generics

JSpecify also works with generics providing some more advanced capabilities

import org.jspecify.nullness.NonNull;

import org.jspecify.nullness.Nullable;

import org.jspecify.nullness.NullMarked;

@NullMarked

public class Result<T, E extends Throwable> {

private final @Nullable T value;

private final @Nullable E error;

private Result(@Nullable T value, @Nullable E error) {

this.value = value;

this.error = error;

}

public static <T, E extends Throwable> Result<T, E> success(@NonNull T value) {

return new Result<>(value, null);

}

public static <T, E extends Throwable> Result<T, E> failure(@NonNull E error) {

return new Result<>(null, error);

}

public boolean isSuccess() {

return error == null;

}

public boolean isFailure() {

return !isSuccess();

}

public @Nullable T getValue() {

return value;

}

public @Nullable E getError() {

return error;

}

public @NonNull T getOrThrow() throws E {

if (isFailure()) {

throw error; // Safe because error is @NonNull in failure case

}

// value could be null if the Result was constructed directly using the private constructor.

if (value == null) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Result was constructed in an invalid state. Value was null despite being a success.");

}

return value;

}

public <U> Result<U, E> map(java.util.function.Function<? super T, ? extends U> mapper) {

if (isFailure()) {

return Result.failure(error);

}

T val = getValue();

if (val == null) {

return Result.failure((E) new IllegalStateException("Value was null despite being a success."));

}

return Result.success(mapper.apply(val));

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Result<String, IllegalArgumentException> successResult = Result.success("Hello");

Result<Integer, IllegalArgumentException> failureResult = Result.failure(new IllegalArgumentException("Invalid argument"));

if (successResult.isSuccess()) {

String message = successResult.getValue();//message can be null if the result was constructed incorrectly.

System.out.println(message.toUpperCase());

}

if (failureResult.isFailure()) {

IllegalArgumentException exception = failureResult.getError();

System.err.println(exception.getMessage());

}

Result<String, Exception> result = Result.success("42");

Result<Integer, Exception> mappedResult = result.map(Integer::parseInt);

System.out.println(mappedResult.getOrThrow() + 1);

Result<String, Exception> badResult = new Result<>(null, null);

badResult.getOrThrow(); //Throws an exception because the result is in an invalid state.

}

}

Lets breakdown what we are doing here

-

@NullMarked: The@NullMarkedannotation on the class simplifies the code so that all types within theResultclass are treated as@NonNullby default unless explicitly marked with@Nullable. -

Generic Type Parameters: The Result class uses two generic type parameters: -T: Represents the type of the successful value. -E: Represents the type of the error, constrained to be aThrowable(or a subclass). -

@NullableAnnotations: -@Nullable T value: Indicates that the value can be null in the case of a failure. -@Nullable E error: Indicates that the error can be null in the case of success. -

Factory Methods: Thesuccess()andfailure()static factory methods make it clearer how to createResultinstances and enforce correct nullness: -success(@NonNull T value): Takes a non-null value and creates a successful Result. -failure(@NonNull E error): Takes a non-null error and creates a failed Result. getOrThrow(): Demonstrates how to safely retrieve the value and handle the error case: - It throws the error if theResultis a failure. - It is annotated with@NonNull T, indicating that it will always return a non-null value if it doesn’t throw an exception. -map(): This allows mapping the value of a successful result to a new type, while propagating the error in case of failure. The important part here is the correct handling of nulls.

While IntelliJ is improving its JSpecify support, you might encounter situations where it doesn’t fully capture all nuances, especially with generics.

This is why I would recommend using static analysis tools directly in your Gradle build:

Benefits and Pitfalls

JSpecify 1.0 brings much-needed standardization and clarity to nullness annotations in Java. By using @Nullable, @NonNull, @NullMarked, and @NullUnmarked, We can can write safer, more predictable code and avoid the common pitfalls of null-related bugs. Integrating JSpecify into your project is straightforward and can be done incrementally, making it an excellent choice for both new and existing Java applications. As Java continues to evolve, null safety is likely to become an even more integral part of the language, with JSpecify playing a key role in this transition.

Benefits:

Early detection of NPEs: Catches potential null pointer exceptions at compile time.Improved code clarity: Clearly expresses nullability intent.Reduced runtime errors: Leads to more robust and reliable code.Standardized approach: Provides a common language for nullness across projects.

Pitfalls:

Initial annotation overhead: Requires effort to annotate existing code.Potential for false positives: Static analysis might sometimes flag safe code.Tooling support is still evolving: IDE and build tool integration is improving but not perfect.

The Future directions for Java and Nullness Annotations

Java is moving towards stronger null-safety mechanisms, and JSpecify plays a key role in that. In the future, the Java language may introduce native support for null-restricted and nullable types, making null-safety an intrinsic part of the type system.

Null-Restricted Types:

The Null-Restricted type, for instance, would be a type that cannot hold null, and would be enforced directly by the Java compiler. Similarly, nullable types would allow null values but with clear constraints, ensuring more predictable behavior when dealing with null.

A couple of recent Java Enhancement Proposals (JEP) in this area - Project Valhalla aims to introduce value types which are immutable class instances without identity - JEP Draft: Null-Restricted Value Class Types (Preview)

The Key Idea:

A null-restricted type is a reference type expressed with the name of a value class followed by the ! symbol. For example, if you have a value class Range, then Range! would be a null-restricted type, meaning that a variable of this type cannot hold a null value.

void printAll(Range! r) {

for (int i = r.start; i < r.end; i++)

System.out.println(i);

}

printAll(new Range(5, 50));

printAll(null); // compiler error

Default Values: Instead of null, a null-restricted type would have a default value (azero instanceof the value class). This zero instance is created by setting each of the class’s instance fields to its own default value.Conversions: Conversions between normal class types and null-restricted types would be possible, similar to how Integer and int can be converted.Enforcement: The compiler would enforce the null restrictions, issuing errors if you try to assign null to a null-restricted type.

This is still a long way off. As of now, JSpecify provides a way to get closer to that vision, with annotations acting as a bridge until stronger null safety features are possibly added to the language itself.