AI’s potential is immense, yet clunky user interfaces and a lack of discoverability are holding it back from seamless adoption. To unlock AI’s true power, we need interfaces that guide, adapt, and engage—moving beyond the blinking cursor to something more intuitive, proactive, and, ultimately, more human.

Every day I find myself reflecting on the gap between the ever-growing capability of AI, and the somewhat modest impact it is having on our day-to-day life. Apple Intelligence was nothing short of a flop, and our in-home assistants (Alexa, Google Home) feel increasingly dumb.

The gaps are also more subtle and exist on a human level too. Some people just seem to ‘get it’ and have developed an intuition for how and where to apply general-purpose AI tools (exemplified by ChatGPT). This is an intuition that is built through trial and error; in order to ‘get it’, you need to invest time in this technology, a trial-and-error process which takes time.

Surely adopting technology shouldn’t be this hard work?

I’m increasingly of belief that one of the biggest challenges we are facing here is the age-old problem of the user interface. We haven’t found the right way to unlock the potential of AI in such a way that it feels natural and friction free.

The blinking cursor problem

The most notable advances that (text based) Generative AI brought to field of AI are:

- General purpose – GenAI is adept at a wide range of tasks, including translation, creative writing, computer coding (and much more besides) and can undertake more nebulous activities such as being “a friend”.

- Human language – The above is unlocked simply by asking. For the more technical among us this is called prompting, but in simple terms, you just talk to the AI.

These combine to create a significant leap forward, a form of AI we’d have struggled to imagine just five years ago.

So how is this awesome power presented to the user? At the moment, almost every general-purpose AI interface presents you with little more than a blinking cursor:

ChatGPT interface

Perplexity interface

Claude interface

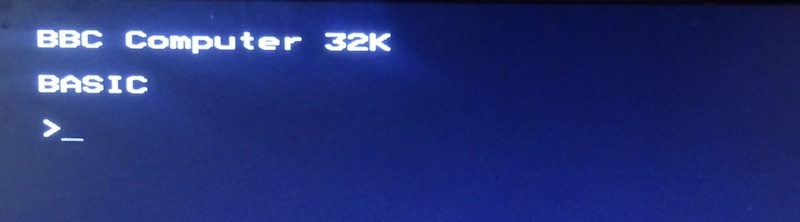

For those of us who’ve been using computers for a while, this is all too familiar. Here’s the interface to the BBC Micro, the first computer I ever used (back in the 1980s):

Back then very few people knew what to do when faced with this screen, and while ChatGPT (and co) are much more powerful than a BBC Micro, the blinking cursor surely evokes the same response - “what am I supposed to type into this box?”, or simply “how do I work this thing?”.

More technical computer users are often happy to experiment (time permitting), whereas less technical or simply less confident users tend to have a fear of “getting it wrong”, informed by years of experience with unforgiving computer interfaces (yes, I’m looking at you Windows … and MacOS … and …) that punish users for their lack of understanding.

The fundamental problem here is a lack of discoverability, where a user must work hard to find and understand the available features or actions within a system. Furthermore, if they are aware that ChatGPT is able to perform a specific task, for example summarisation of meeting notes, it lacks the affordances that guide the user towards successful completion of this task.

The blinking cursor of both the BBC Micro and ChatGPT do little to aid discoverability or provide affordances to guide users.

Lead by example

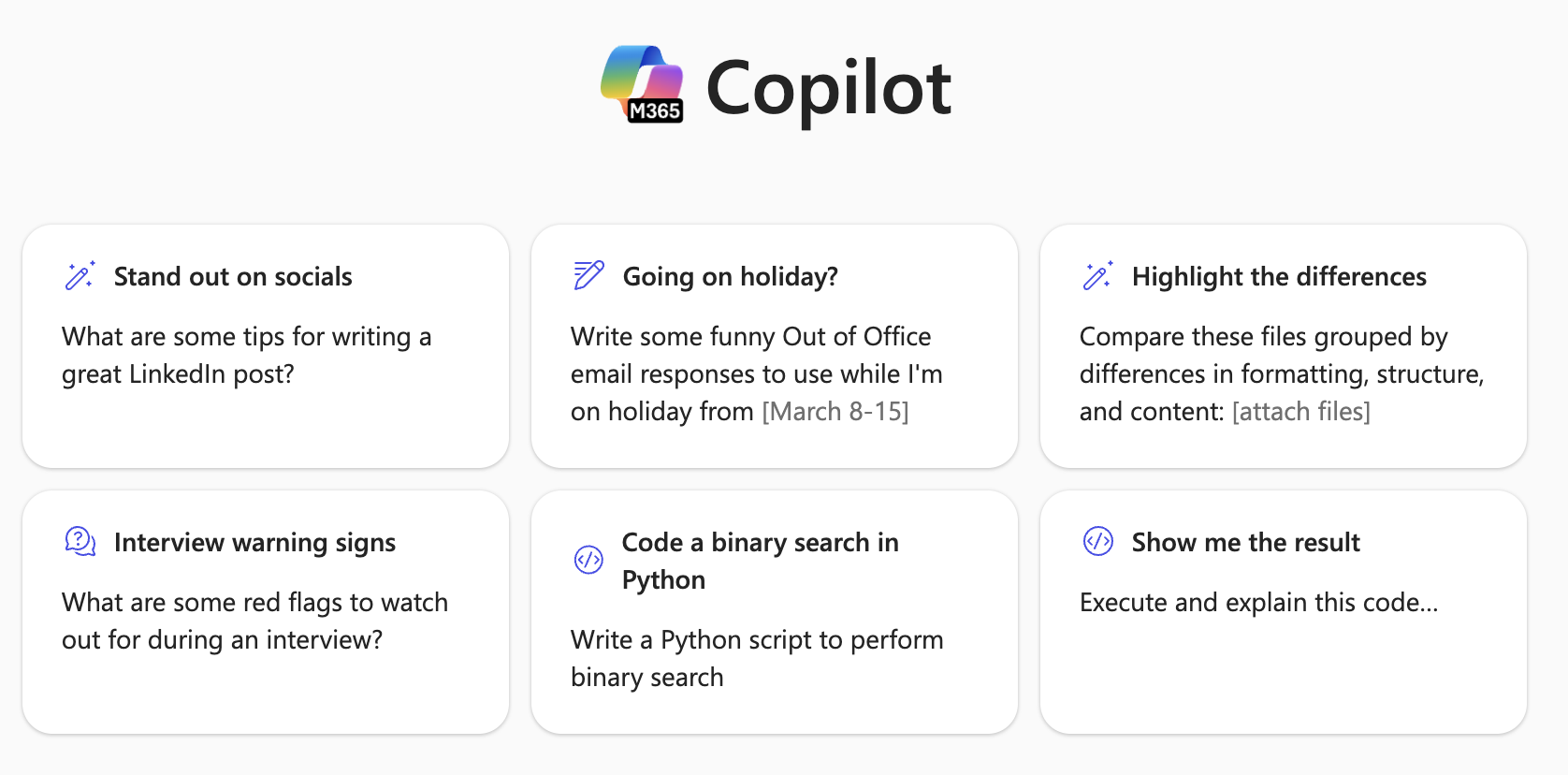

Some of the general-purpose AI interfaces tackle this problem by providing several examples that illustrate the breadth of capability. Here’s Microsoft’s Copilot:

Copilot takes this a step further by providing a prompt gallery, which helps people explore the art of the possible.

Unclear capabilities

Once you’ve overcome the intimidation of the blinking cursor and typed something in, one of the next obstacles you’ll likely meet is the lack of clarity regarding the overall capabilities of these general-purpose AI systems. These systems have been designed to respond in a very positive (and sometimes sycophantic) fashion and will happily undertake a range of tasks for you. However, they do little to help you understand how capable they are of a given task and how well they will respond to your instructions.

The most well-known problem is that of hallucinations, where the AI confidently provides a factually incorrect response in a highly plausible way. However, the problem goes deeper than just fabrication of falsehoods. These AI systems are not able to describe their own capabilities or strengths and are not aware of their limitations and weaknesses. Whilst chain of thought reasoning partially addresses this, it falls far short of the metacognition that allows human beings to confidently state facts.

The problem is further exacerbated by our collective belief that computers are always right. With traditional (non AI) applications, if the computer gives a wrong answer, it is considered a bug that needs fixed. The expected, or desired behaviour is perfection and repeatability.

With the types of tasks that Generative AI excels at (for example creative writing), beyond obvious factual inaccuracies, there may not be a clear right or wrong answer. The quality of the output is subjective and the overall capability of the AI tool in performing a given task is something we must learn through experience.

We’re simply not used to computers giving us answers that are anything other than correct.

Hidden strengths

But AI doesn’t just hide its weaknesses; it also hides its strengths!

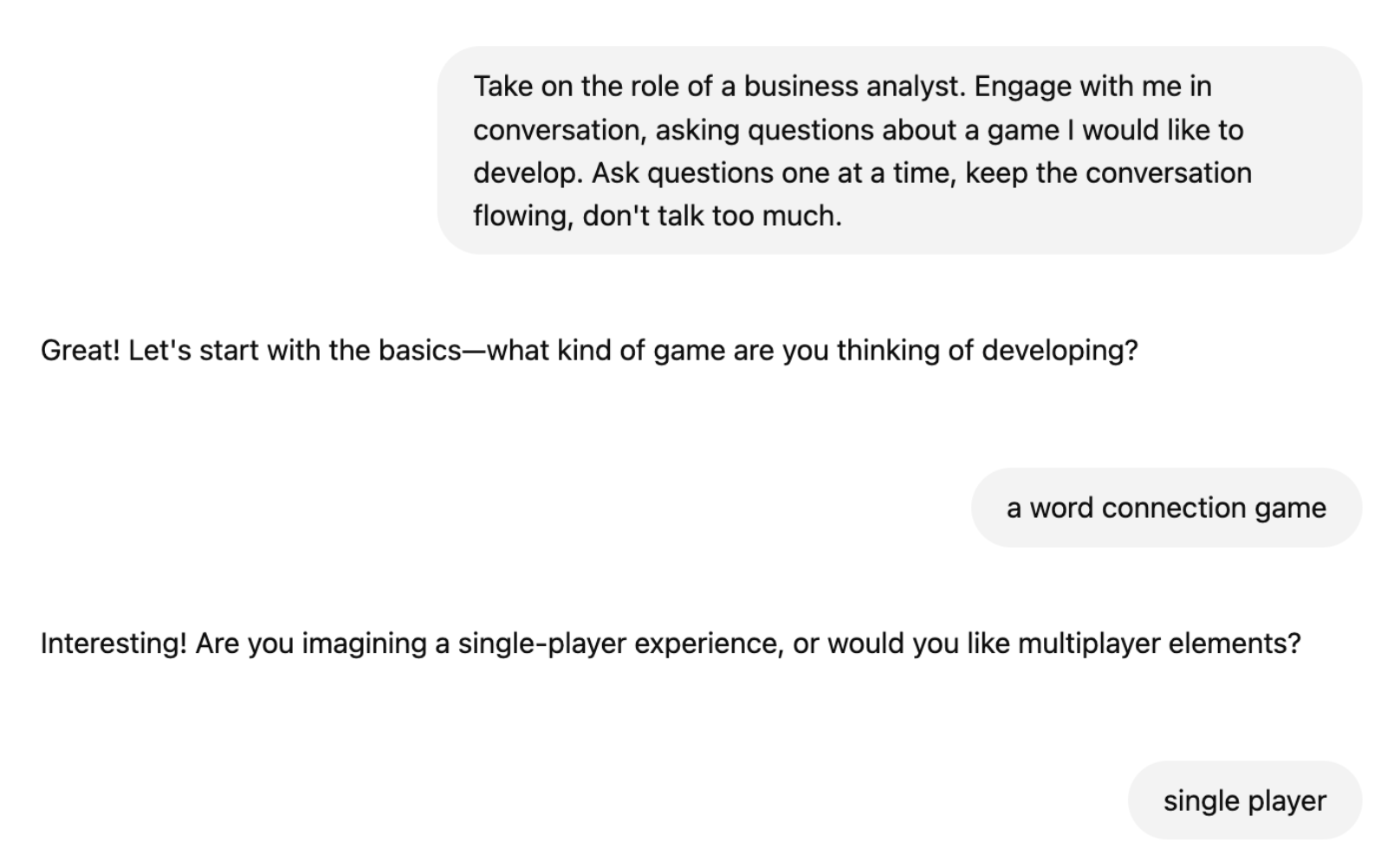

As an example, the standard UI paradigm for using ChatGPT-style interfaces has the human in the driving seat. We ask questions, the AI responds. However, it doesn’t have to be this way. You can ask the AI to turn the tables and drive the conversation; a technique that can be highly effective in some contexts.

For example, you can ask it to take on the role of business analyst and illicit the requirements for a software product:

I continued the above conversation for about 5 minutes, and when the AI analyst was done, asked it to write up the conversation as a formal use case specification. Impressive.

Another notable feature you tend to learn about general purpose AI is that it is incredibly effective at document transformation or interrogation. e.g. “summarise this document”, or “turn this transcript into a blog post”. This significantly limits the risk of hallucination. You can also ask it to perform some very subtle transformations, “make this case study a little more modest in tone”.

Unfortunately, none of these strengths or weaknesses are discoverable.

Finding equivalents and metaphors

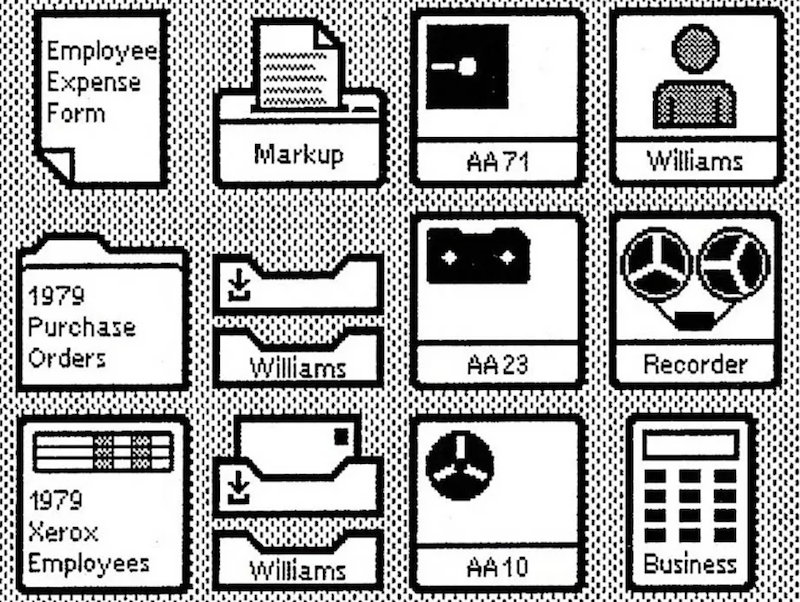

Early computers removed the blinking cursor with graphical user interfaces:

The Xerox Alto UI, 1973

Not only did this help improve discoverability, by giving people visuals cues regarding the functionality of the computer – they also helped people understand the underlying capabilities of the computer through real-world metaphors. For example, to help people understand that computers can digitally store information, the interface draws a parallel with physical equivalents such as filling cabinets. This gave rise to the well-known term What You See Is What You Get (WYSIWYG), which has shaped user interfaces ever since.

It would seem impossible to illustrate the full breadth of capabilities that Generative AI could offer through a single visual interface. A more creative approach which some are researching is the notion of Generative UI where a user interface is dynamically created by the AI, based on the current conversation.

A human metaphor

The blinking cursor interface presented by AI systems isn’t that far removed from the interface presented by human beings. We don’t walk around presenting a clear outline of our capabilities and the tasks we can perform; we lack a comprehensive or accessible user interface.

Our capabilities are expressed both directly and indirectly in a variety of ways. Here are just a couple of examples:

- Job title – in the world of business our job title is a primary indicator of our capabilities. At a stretch one software engineer in your team is largely interchangeable for another, the same is true of copywriters or financial controllers

- Job role – outside of the world of business job role is almost entirely interchangeable, we consider one doctor to be largely equivalent to another, and the same is true for electricians and builders.

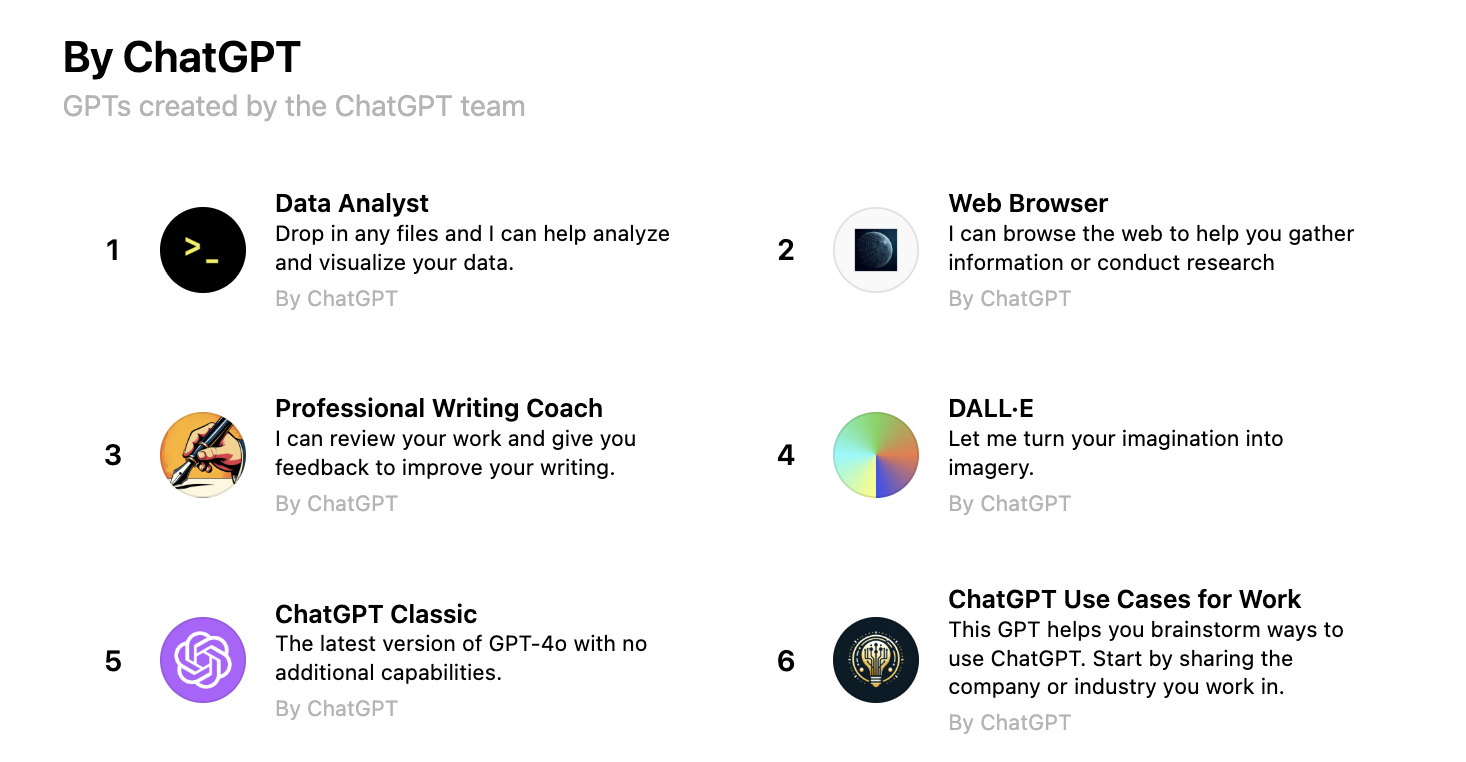

We see something similar with OpenAIs custom GPTs, that use extra knowledge and instructions to adopt a narrower role. While this technique allows you to supplement the foundational model with extra data and instructions, personally I think the main advantage of custom GPTs stems from them being quite clear about what you can do with each AI tool. You can also browser the various GPTs via a ‘store’:

While this narrowing of capabilities helps discoverability, it does feel like this approach suppresses one of the most notable aspects of Generative AI, that it is general purpose.

Humans have roles which may be formal and long-lived (software engineer, doctor), or more informal (coach, mentor, friend) and have the ability to change roles based on circumstance. We also learn more about the capabilities, strengths and weaknesses of our fellow humans through experience and relationships. Could we do the same with AI?

Science fiction often does a good job of predicting the societal impacts of technology, and in the case of general-purpose AI this tends to be presented as a companion, or friend. For example, Tony Stark’s relationship with JARVIS is conversational and warm, it is far from just being transactional.

This might sound a bit ridiculous, but to get the most out of AI, I think we’re going to have to find a way to build a relationship with it (no … not that kind). We need to:

- Forgive errors – allow AI to make mistakes, change our perspective that computers are always right. Understand that its greatest value is often delivered through tasks that have a subjective level of quality.

- Invest time (in this relationship) - learn its strengths and weaknesses

But on the flip-side, the AI interface needs to evolve to:

- Adopt roles – understand that depending on context, the user will have very different needs and expectations

- Environmental awareness – in support of the above. This doesn’t have to be vision, or audio, it simply needs to understand the basics, is this a home or work environment?

- Learn about us – some of the chat interfaces have ‘memory’, but at the moment this is quite shallow. Ideally the AI should adapt to use our language, understand our moods and personal values.

- Be an active part of the conversation – rather than waiting for us to start the conversation, why not be proactive? “what have you got planned for the day?”, and offer up targeted support

- Better understand its own weaknesses – from a technical perspective this is probably the greatest challenge. I’d much prefer working with an AI that is able to express its own strengths and weaknesses

The five points above could simply be described as “be more human”.

A final point I want to make is that of trust. Our expectation that computers are deterministic and always right almost immediately leads to us trusting their output. Whereas an AI system that behaves as I describe above is probably something that wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) immediately earn your trust, although the characteristics and behaviours described could lead to trust.

Conclusions

In many ways, AI interfaces mirror human interactions—imperfect, contextual, and evolving. The key to making AI more effective is to acknowledge these realities and build interfaces that feel less like command lines and more like intuitive, supportive collaborators.

The blinking cursor isn’t the future. The future is AI that guides, adapts, and engages. The future is AI that feels more human.

This post generated a lively debate over on Hacker News.