LLMs are not just limited by hallucinations—they fundamentally lack awareness of their own capabilities, making them overconfident in executing tasks they don’t fully understand. While “vibe coding” embraces AI’s ability to generate quick solutions, true progress lies in models that can acknowledge ambiguity, seek clarification, and recognise when they are out of their depth.

The pace of model development has slowed somewhat, with some expressing disappointment in the most recent GPT4.5. However, by over-indexing on the race for AGI and benchmark performance we are looking at the wrong things. The most widely reported and understood weakness of LLMs is their tendency to hallucinate, where the model output is factually incorrect, yet highly believable.

This is of course a limiting factor, but there are others. One that I think is less widely reported but potentially has a more detrimental impact on the usefulness of LLMs is their lack of awareness of their own capabilities. They are not self-aware, and no, I don’t mean that they lack sentience.

They simply don’t know what they are good at, and what they are bad at. They don’t know what is feasible, and what is not.

Vibe Coding

Just a few weeks ago Andrej Karpathy (a founding member of OpenAI) coined a term, vibe coding, which has taken the tech world by storm, triggering articles in the popular press, such as this one from New York Times a few days ago.

The gist of vibe coding is simple, let your AI tools worry about the code, you just instruct (prompt) the AI to do your bidding. To quote Andrej “I just see stuff, say stuff, run stuff, and copy paste stuff, and it mostly works.”. Vibes.

You might think that hallucinations would have a significant impact on vibe coding (vibe coders?), however, Simon Willison argues that the impact of hallucinations is quite minimal because the compiler, or runtime, will pick up when the LLM “imagines” a library or a function.

So does this mean we are safe to vibe?

No, far from it. LLMs have a subtle, yet more dangerous weakness – their lack of awareness.

Vague requirements

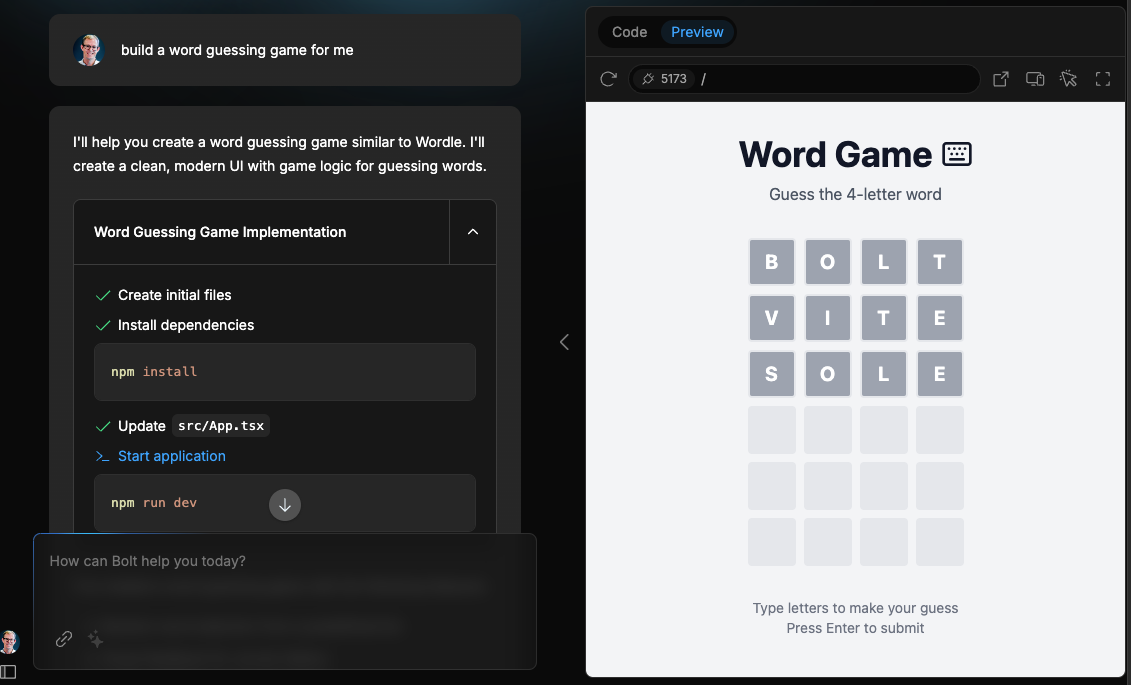

Let’s use bolt (which incidentally I think is an amazing tool) for an illustration. If I simply ask it to “build a word guessing game for me”, it very rapidly builds “something”. It creates a UI, and a half-working implementation of some sort of game:

While this initially looks rather impressive, if you compare this to how a human would respond to the same request, there are some significant differences. An engineer, no matter how junior they are, would understand that a seven-word request is full of ambiguity. Going ahead and building something based on this “requirement” would be a futile exercise.

A human would seek clarification, they would have a mental model of the information required to sufficiently describe the task. They’d also have enough experience to understand that they don’t need to know everything or have detailed requirements, tasks (whether programming or not) can be iterative and collaborative.

Bolt knows none of this and proudly presents its Word Game as though it were the finished article.

Poor understanding of their own limitations

All LLM-based tools that I have used seem to lack an understanding of their own limitations. If you ask them to undertake a task that is far beyond their capabilities, they will valiantly give it a try, and utterly fail!

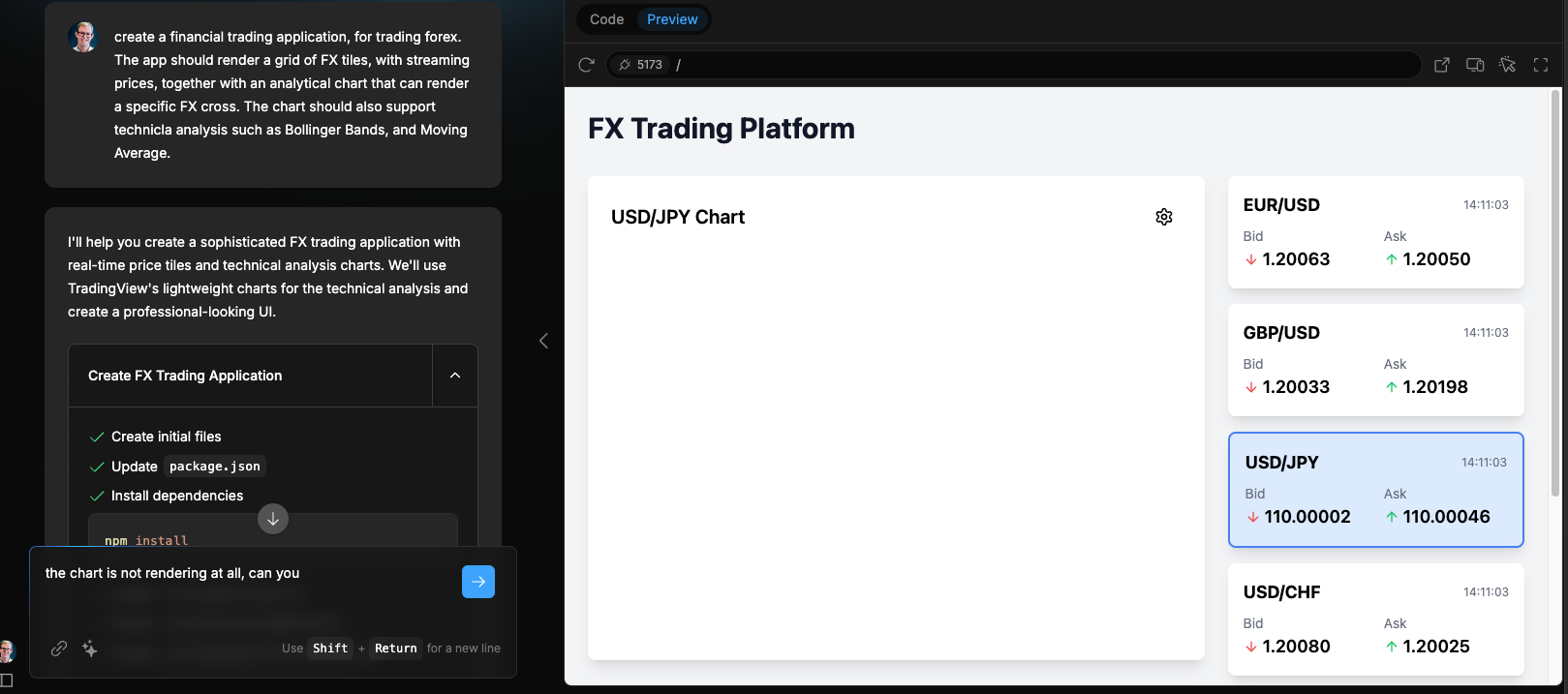

Again, using Bolt as an example, I have asked it to build something quite complicated, an FX trading application:

It has made a valiant attempt, rendering some tiles and a chart (which incidentally doesn’t work). However, it is little more than a mock-up, it certainly isn’t a trading application.

When vibe coding, the LLM ignores ambiguity and tried its best. As a result, you can very rapidly build completely the wrong thing. As others have stated, when using AI to accelerate development, you simply must invest more time in testing.

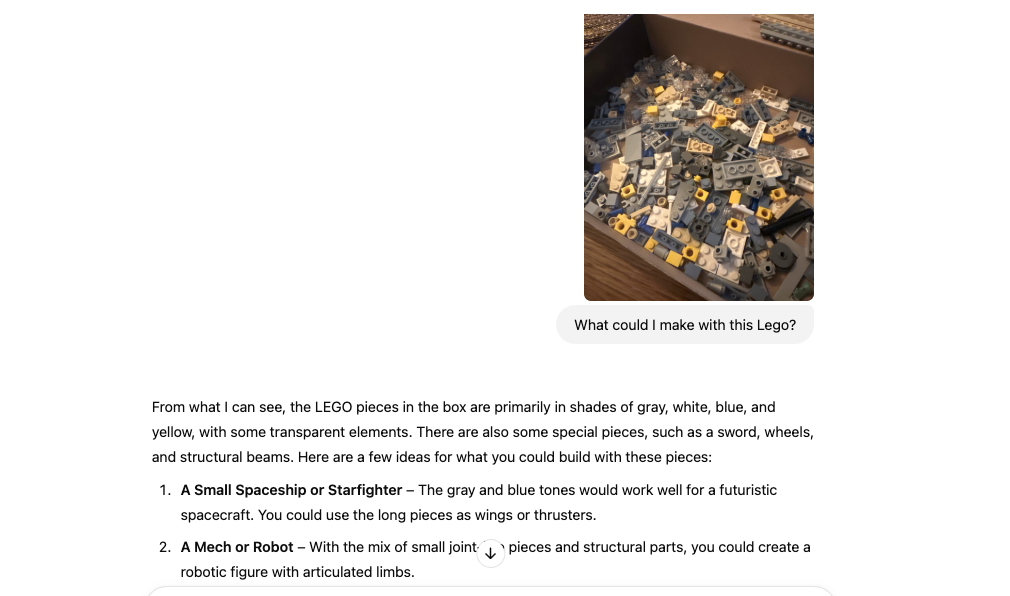

But back to understanding limitations, this isn’t just a Bolt problem. Here’s a conversation I had with ChatGPT last night, where I took a photo of some lego and asked for some build ideas:

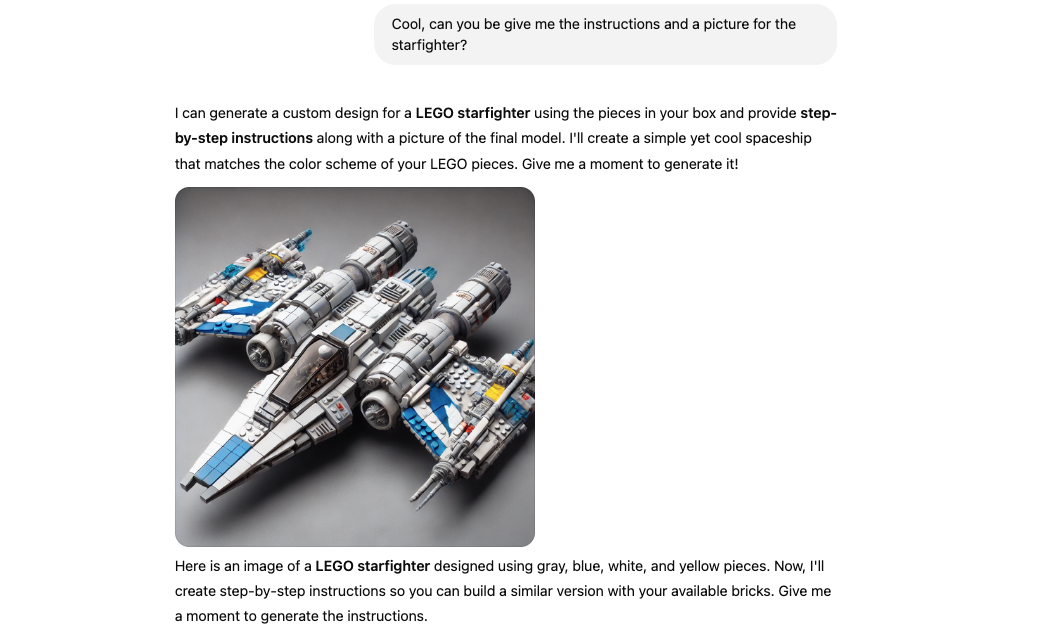

It made a good start, and when I asked it to elaborate on the spaceship idea, providing build instructions, again, it started strong – rendering an impressive Lego model:

But when it came to the instructions themselves … oh dear …

Step-by-Step LEGO Starfighter Instructions

Step 1: Build the Main Body

Base Construction:

- Lay out a 4x8 plate as the central fuselage.

- Stack 1x2 and 2x2 bricks on top to add height.

- Attach a sloped brick at the front for an aerodynamic shape.

Cockpit Section:

- Use a 1x4 clear or black piece to act as the windshield.

- Add angled slopes to frame the cockpit.

Step 2: Add the Wings

Wing Framework:

- Connect 4x6 or 6x6 plates on either side of the fuselage.

- Reinforce them with angled bricks for structure.

Weapon Attachments:

- Place 1x1 clips at the wing edges to hold small rods or antennas.

- Attach cylindrical LEGO elements for cannons.

[... the instructions continue ...]

The instructions are laughably simplistic when compared to the beautifully rendered and complex Lego model shown earlier.

Creating the detailed build instructions for a large Lego model is a complex task. It is not dissimilar to the task of creating an FX trading platform.

But once again, the LLM is unaware of the complexity of this task, and its own limitations. It simply gives it a try and fails miserably!

Conclusions

The more I use LLMs for a wide range of tasks, the more I hit against this fundamental issue. Hallucinations are of course an issue too, but they seem quite minor in comparison. I can live with occasional factual errors, and the need to review the output. I find it harder to work with a system that will happily undertake any task, whether it is simple, yet ambiguous, or complex and far beyond its own capabilities.

For now, the path to success involves trial and error, to build up our own mental model of the capabilities of an LLM (or LLM-based tool). This is time-consuming and is never going to be terribly precise, as of course their capabilities lack clear boundaries.

I am still incredibly optimistic about LLMs and their utility, but we don’t need models that perform even better on some abstract benchmarks, we need models and tools that respond “no, I’m afraid I cannot do that”, or “can we break this task down”, or “can we discuss this a bit further”.

That would be real progress.

This post generated a lively debate over on Hacker News.