This post outlines a general purpose alternative to ArrayLists which provide lazy insertions and deletions to speed up those operations. The Java source code, unit tests, javadoc and jar file for all the classes mentioned in this blog is available here:scottlogic-utils-mr.zip.

ArrayLists are perfect when you want to get elements by their indices but not so brilliant when you want to insert or remove elements. In a previous post, I showed how a balanced binary search tree can be designed to work as if it's an extendable array, this approach offers faster removals and insertions at the cost of more time to get elements. In this post, I'll go through an implementation of a new list (at least I don't know what the name for it is, if it has one already!) which attempts to marry up these two approaches, offering improved speed on all operations over the binary tree based list by being lazy.

I call this new list a "PatchWorkArray" because it stores its data in patches throughout a regular ArrayList. The idea behind it is this: Suppose you've got a list with a large number of elements in it and want to remove the element at index i, where i < n, and n is the number of elements in the list; instead of moving elements i+1 to n up one place (which is what happens in an ArrayList), you could just leave the list as is, then, when someone asks for the element at index j, where j >= i, you just give them the element at index j+1 instead.

The PatchWorkArray generalizes this idea; it's an ArrayList (the "backing list") and an associated set of alterations (insertions and removals) to that ArrayList. When an element is requested, the set of alterations is queried to figure out the correct location of the element in the backing list, which is then returned.

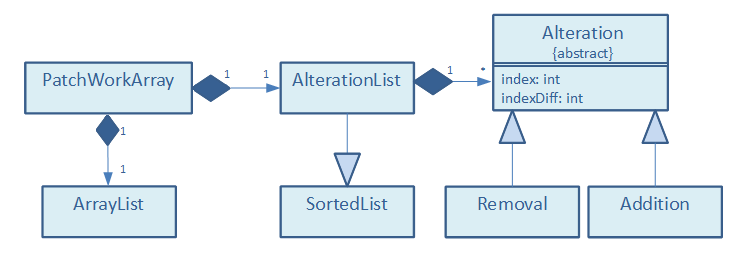

The relationship between the various classes involved is described in the following UML diagram:

Dealing with AlterationsThe PatchWorkArray doesn't do anything special about removals or insertions made to the end of the list - they simply get performed on the backing list itself. However, the effect differs for alterations made at any other position. When an element is removed, instead of removing the corresponding element from the backing list, it is instead replaced with a dummy value. When an element is inserted, the element currently in the corresponding position in the backing list is replaced with a new sub-list containing the newly inserted element followed by the replaced one. This sub-list is an instance of a binary tree based list, which allows log time insertions and removal by index. Further deletions and insertions at indices covered by this sub-list are then performed on the sub-list itself, rather than affecting the backing list.

For example, suppose you have a PatchWorkArray storing the numbers 0 to 9, in the most simple case the backing list would look like so:

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

If you then removed the element at index 2, then inserted -1 at index 6, the backing list would appear like so:

[0, 1, R, 3, 4, 5, 6, [-1, 7], 8, 9]

where the 'R' represents the dummy value. Note that indices start from index 0 and that when we inserted the -1 at index 6, this actually causes a sub-list to be created at index 7 in the backing list, due to the removal we made before. To make rapid searching of the list possible, the PatchWorkArray needs to store an alternative representation of the alterations that have been made.

In this representation, alterations are represented by simple Java objects (instances of the Alteration class) with two key integer properties: index, and indexDiff. Index is the index in the backing list at which the alteration occurs and is unique. IndexDiff is the difference to the index that the alteration makes when you're searching for an element; if that sounds a bit abstract now, not to worry, as hopefully it'll become clearer later on. Removal and Addition are the two concrete subclasses of Alteration. A Removal object represents a block of consecutive removals in the backing list starting at the index position; its indexDiff is set to the number of removed elements. Additions have negative indexDiffs equal to one minus the size of the sub-list at the index in the backing list.

For example, you can have a PatchWorkArray, once again storing the numbers 0 to 9, with a backing list that looks like this:

[R, R, R, 0, 1, [2, 3, 4], 5, R, 6, [7, 8], 9].

If this were the case, the following Alterations would need to be stored:

| Type | Index | IndexDiff |

|---|---|---|

Removal |

0 | 3 |

Addition |

5 | -2 |

Removal |

7 | 1 |

Addition |

9 | -1 |

The data structure that stores these Alterations is an instance of AlterationList, a subclass of the SortedList class I wrote for a previous post, and is relatively complicated in itself. It's a balanced binary search tree (actually an AVL tree) that stores Alterations in order of their indices, where each node in the tree caches the sum total of all the indexDiffs of its descendants.

The AlterationList class has only one key method with the signature ArrrayLocation getLocationOf(int index), which takes an index of an element in the PatchWorkArray and returns the position it would expect to find it in the backing list. This position is represented as a simple object (an instance of ArrayLocation) which is effectively a wrapper for two integers - the requested element's index in the backing list and, if appropriate, its index in the sub-list at that index. The getLocationOf method is similar to a binary tree search, other than the fact that each time we encounter a node whilst traversing, it needs to update the index of the element its looking for, based on the Alteration at that node and the Alterations in its left sub-tree (those with smaller indices). The commented source code for this method is given below:

ArrayLocation getLocationOf(final int index){

int mainIndex = index; //the index in the backing list that contains the value we want (updated as the search progresses)..

int subIndex = -1; //the index of the sub-list that contains the value we want (-1 means no sub-index)..

AlterationNode current = (AlterationNode) getRoot();

while(current != null){

//get the alteration of the node..

Alteration alt = current.getValue();

//the change that the current alteration makes to smaller indices make..

AlterationNode leftChild = (AlterationNode) current.getLeftChild();

int leftSideDiff = (leftChild == null) ? 0 : leftChild.totalIndexDiff();

//what's the index taking into account what happens in the smaller indices..

int adjustedIndex = mainIndex + leftSideDiff;

//this alteration occurs at an index too big to affect us..

if(adjustedIndex < alt.index){

current = leftChild;

} else { //case that this index will affect the index we want to find..

if(alt.indexDiff < 0){ //it's an Addition so may be we need to return a sub index..

//smallest and largest indices of elements that being stored in sub list...

int smallestIndexInSubArray = alt.index - leftSideDiff;

int largestIndexInSubArray = smallestIndexInSubArray + Math.abs(alt.indexDiff);

//case that we want an element in this location..

if(mainIndex <= largestIndexInSubArray){

subIndex = mainIndex-smallestIndexInSubArray;

mainIndex = alt.index;

break;

} else { //(mainIndex > largestIndexInSubArray)

current = (AlterationNode) current.getRightChild();

mainIndex = adjustedIndex + alt.indexDiff;

}

} else { //alt instanceof Removal

current = (AlterationNode) current.getRightChild();

mainIndex = adjustedIndex + alt.indexDiff; //need to change what we are looking for..

}

}

}

return new ArrayLocation(mainIndex, subIndex);

}With the getLocationOf method in place, the PatchWorkArray's code is greatly simplified, for example, the get method of the PatchWorkArray is fairly straight forward and looks like this:

public T get(int index) {

if(index < 0 || index >= size()){

throw new IllegalArgumentException(index + " is not valid index.");

}

ArrayLocation loc = alterations.getLocationOf(index);

return (loc.hasSubListIndex())

? ((List<T>) backingList.get(loc.backingListIndex)).get(loc.subListIndex)

: (T) backingList.get(loc.backingListIndex);

}Note that in this case, the PatchWorkArray is parameterised by the type T, but the backing list is actually an instance of List<Object>. This is because the backing list has to store sub-lists and dummy values as well as objects of type T, hence the use of casting.

The Advantage of LazinessAlthough it's clear that lazily removing and inserting elements can make these operations faster; being lazy has another advantage - it gives you the opportunity to optimise the data structure over a series of operations. In a simple case, imagine you remove the element at index zero from a list, then, afterwards, insert a new element at that index. If the list is an ArrayList, this would involve copying the whole array twice. However, if it's a PatchWorkArray, making these changes only requires a constant number of operations and what's more, thanks to some optimisations, you are left with a backing list which is an exact match of the equivalent ArrayList (i.e. its AlterationList is empty).

The optimisations carried out in the PatchWorkArray are relatively simple and are by no means pushing the boundaries of what could be achieved with more time and attention. These optimisations can be considered "local" since they work only by considering what's happening in the indices directly next to where a change is being made. They are implemented in the add and remove methods of the PatchWorkArray class and are an attempt to reduce the number of alterations to the backing list when making a change. They ensure that consecutive blocks of dummy values in the backing list are represented by a single Removal in the AlterationList and that indices holding dummy values are used to store newly inserted elements whenever possible. The following simple examples show these local optimisations at work and how insertions and removals affect the state of a PatchWorkArray:

| Before | Operation | After | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backing List | Alterations | BackingList | Alterations | ||||||

| Type | Index | IndexDiff | Type | Index | IndexDiff | ||||

| 1 | [R, 1, R, 2] | Removal |

0 | 1 | remove(0) |

[R, R, R, 2] | Removal |

0 | 3 |

Removal |

2 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 | [9, 8, R, 7] | Removal |

2 | 1 | add(2, -1) |

[9, 8, -1, 7] | |||

In example one, an element is removed which has dummy values to the left and right, causing the entire block of dummy values to be represented by a single Removal in the AlterationList. In the second example, an element is added to a position where it can replace a dummy value, causing the AlterationList to be emptied.

PerformanceThe asymptotic runtime of the PatchWorkArray methods are slightly harder to quantify than those in regular data structures as they are dependent on its alterations, rather than the number of elements in it. The important metric, which I call the "performance hit" is the number of Removals plus the sum of the absolute index diffs of all the Additions. Note that this metric can never be greater than one plus the number of elements in the backing list, since consecutive removals are represented using a single Removal object. Although it's not strictly true, I like to think of this metric as a measure of where the PatchWorkArray lies between an ArrayList and a binary tree based list; if the performance hit is zero, its backing list is pretty close to the equivalent ArrayList, if it's close to the number of elements in the list, then it's likely that it contains at least one large binary-tree based sub-list.

The asymptotic worst-case runtimes of various operations on a PatchWorkArray and other list implementations are given below, where n is the number of elements in the list and p is the performance hit of the PatchWorkArray:

| Adding To By Index | Removing From By Index | Get by Index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Middle | End | Front | Middle | End | ||

| LinkedList | O(1) | O(n) | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) | O(1) | O(n) |

| ArrayList/Vector | O(n) | O(n) | O(1)* | O(n) | O(n) | O(1)* | O(1) |

| UnsortedList (binary tree based list) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) | O(log(n)) |

| PatchWorkArray | O(log(p)) | O(log(p)) | O(1)* | O(log(p)) | O(log(p)) | O(log(p))** | O(log(p)) |

| (* amortized constant time - running the method k times takes O(k) time, ** if the removal is from the end of the backing list the time taken is O(1)*, if however the end of the PatchWorkArray is not the end of the backing list, the time required is O(log(p)). | |||||||

I suppose you could call it cheating to say that theoretically the performance of a PatchWorkArray is superior to that of a binary tree based list, since it's possible that p = n + 1. However, the point is p can be controlled separately from n, and in practice, it's likely that p is significantly smaller than n anyway.

Other "Non-Trivial" MethodsThe PatchWorkArray contains a fair amount of code and took a quite lot more time than I anticipated, especially owing to the fact that I needed a binary-tree based list implementation first! Apart from the add and remove methods which perform the optimisations, the other technically involved code is in the internal implementation of the Iterator interface returned by the iterator method, and in the fix method, which is unique to this type of list.

I won't go through it here (as the code is pretty long and rather ugly!), but the Iterator implementation allows the PatchWorkArray to be iterated over in linear time in the number of elements in the list. This is more difficult than you might think, owing to the fact that this number is potentially far smaller than the number of dummy values in the list. The fix method however is worth considering; its purpose is to resolve the alterations in the backing list so that it becomes effectively just like the equivalent ArrayList. The runtime for this method is linear in the number of elements in the list too. The idea is that this method be called periodically, or when required, to allow the PatchWorkArray to operate with maximum efficiency. The commented source code for this method is given below:

public void fix(){

//the new backing list and the next index to add to..

List<Object> fixedList = new ArrayList<Object>(size());

Iterator<Alteration> itr = alterations.iterator();

int blIndex = 0; //index into backing list..

while(itr.hasNext()){

Alteration alt = itr.next();

int altIndex = alt.index;

//copy the elements from blIndex to altIndex-1..

for(; blIndex < altIndex; blIndex++){

fixedList.add(backingList.get(blIndex));

}

if(alt.indexDiff > 0){ //alt instanceof Removal..

blIndex += alt.size();

} else { //alt instanceof Addition..

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

Iterator<Object> subListItr = ((List<Object>) backingList.get(altIndex)).iterator();

while(subListItr.hasNext()){

fixedList.add(subListItr.next());

}

blIndex++;

}

}

//copy in the final elements..

for(int size=backingList.size(); blIndex < size; blIndex++){

fixedList.add(backingList.get(blIndex));

}

backingList = fixedList;

alterations.clear();

modCount++;

}This method works by creating a new ArrayList, which will form the new "fixed" backing list, then filling in the elements by iterating over the AlterationList, rather than the backing list itself. This is crucial in order to keep the process linear. The method ends with simply switching the backing list for the new list and resetting the alterations. The call to increment modCount enables iterators going through this PatchWorkArray to fail on a best effort basis, for more information see AbstractList, which is an ancestor of the PatchWorkArray class.

In the next post, I'll go through how to use effectively subclass and use the PatchWorkArray class and show how it compares in empirical tests to other List implementations. Meanwhile, feel free to try it out and let me know what you think. I've written a fair number of unit tests, which are included in the download, so hopefully it's all working asexpected (especially as it really isn't the easiest thing to debug!), but if you come across an issue please let me know.

Mark Rhodes