Android targets a wide user base. It runs on budget to high-end phones and tablets, digital cameras and even refrigerators! In its short lifetime, several major versions have been shipped. This proliferation has been described as the ‘fragmentation’ of the platform.

Looking at the numbers; OpenSignal detected 11,868 distinct Android devices this year, up 200% from 2012. Gingerbread (an Android version that is 2 ½ years old), still accounts for 30% of devices. Whilst these numbers can be considered rock-solid, they’re only really painting a picture of what’s intended by design - Android is fragmented. It’s a feature, not a bug!

What truly matters is the impact this has on developers and product owners. Fragmentation is a problem if applications are difficult to develop, maintain and market. By looking at some of the key attributes and supporting mechanisms of the platform, we can assess whether Android’s fragmented nature is a strength or weakness.

Handling different screen sizes

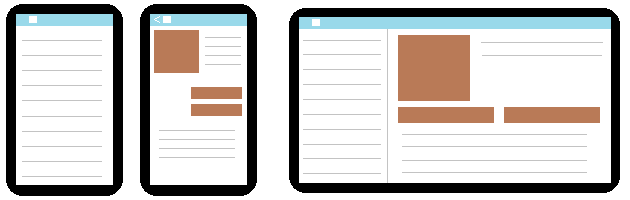

With such a wide variety of devices, how is it possible to make sure your app looks great everywhere? The solution is to design with this in mind. Responsive design involves adapting the UI such that it is optimized for the user’s advice. Layouts displayed individually on a phone may be combined into a multi-column layout on tablets. Adaptations apply at the micro level too, with flexible margins for content to scale and fit a new boundary, and images displaying at an appropriate resolution.

Android supports, indeed encourages, this style of design. Images, layouts, colours and strings are all loaded dynamically. Apps can therefore provide multiple versions of an asset for different situations and let the system choose the most appropriate resource, based upon the device configuration. It’s possible to load a resource based on screen size, OS version, screen orientation, language - or a combination of these!

What’s great about how Android approaches this solution is that it is flexible. You can buy into as much or as little as your app needs to work. If you want your app to look the same everywhere, it can. Android does its best to help you out. This flexibility also extends to when you need to tweak something for a particular form factor - the scope of the change is limited.

Part of getting a responsive design right is rigorous testing. This is especially essential when there is code that reacts differently based upon the device configuration. Using Android’s emulator, developers can simulate a device according to some custom specification - such as screen size, hardware and OS version - and test the app. There is a risk bugs can be introduced, causing behaviour to differ between devices. You do not need to test every possible combination, but rather focus on well-established form factors and then think about edge cases.

Overall, responsive design somewhat future-proofs your application. If a new 15” tablet is released tomorrow, your UI will scale and arrange itself appropriately so that it looks good. There is no need for you to release multiple versions of an application, one to target phones, another for tablets and so on. Admittedly, creating and testing responsive layouts incurs a larger development cost, but this is somewhat mitigated by the wealth of tooling support available and the benefit of being flexible enough to look great on all devices.

Android OS Version Changes

Between Gingerbread and Ice Cream Sandwich, Android did a lot of growing up! Honeycomb was a tablet-only version of Android, including a new visual style, the Fragments API (a key component in creating multi-column layouts) and the Action Bar design pattern. These changes were made available to all devices with Ice Cream Sandwich.

Alone, these additions are welcome, but not useful to apps which would like to support versions of Android before Honeycomb, too. To avoid this predicament, Google packages up re-implementations of these new APIs as part of its Android Support Library package. This is compatible with older versions of Android and mirrors the native APIs. Developers can very quickly hook it into their applications to bypass lots of platform-specific behaviours and UI inconsistencies.

Not all API changes can be backported. A simple example is when APIs are added to support a new hardware feature. Furthermore, there have been bugs found in the Support Library. However, the support library significantly reduces the cost of fragmentation, by providing consistency in looks and behaviours between platforms. Developers aren’t left to completely re-implement core Android elements!

New OS versions are stricter than previous versions. This is normally done for security or efficiency reasons. For example, a change was made recently to further restrict costly operations during UI layout. Following the strict guidelines can benefit all versions - especially so for older devices where processor speeds and memory are lower.

In the case where APIs are superseded by new OS versions, you have a choice on the course of action to take:

-

Always use the old API. This is the easiest option, as it involves no extra code. However, it does mean that your app does not take advantage of new features available in the new API.

-

Use the most appropriate API. Add some code to detect which version a device is running, and use the most appropriate API. This technique is often used to handle small behavioural differences between platforms, but can be extended to full features. A consequence is that features introduced in new APIs will not be available to incompatible devices, so the functionality of your app diverges by OS version.

-

Reimplement the new API. Just like the Android Support Library, you can opt to use the native API where it is supported, and provide your own implementation where it is not. This involves the largest cost in terms of development, but comes with a great benefit of cross-OS-version consistency.

Taking this decision on a feature-by-feature basis is most appropriate, as no “one size fits all” solution exists. Assessing the business value of each feature can often determine the method to overcome the platform inconsistency.

Android handles OS differences primarily through its supporting infrastructure, such as the Android Support Library. The resourcing system encountered previously also plays a role (it is possible to provide different UI styles for different OS versions). However, it is inevitable that version differences can result in bespoke solutions, which come at a cost.

Security

One final factor to consider is how fragmentation affects security. Security considerations are fourfold:

-

Security vulnerabilities in a manufacturer’s custom code. Device manufacturers ship lots of additional material with the stock Android code. Samsung and HTC, for example, add their own UI layer and pre-installed applications to create a consistent look and feel for their range of Android devices. Alongside this are bootloaders and device drivers. Vulnerability in this code is the responsibility of the manufacturer and not the core Android team; although they do work in close collaboration when such vulnerabilities are found. Working around these issues can be extremely costly and tricky, although they are a rare occurrence.

-

Security mechanisms shipped in new Android versions. New versions of Android do not ship to all devices. The consequence is that new security mechanisms, such as application verification, are restricted to the devices that can support the new version, and receive an update. Of course, this risks introducing behavioural inconsistencies between platforms, requiring either workaround code, or updating code to follow new best practice. Implementing such changes comes at a cost of added development. Furthermore; existing mechanisms are strengthened in newer OS versions. Typically reacting to these changes involves making a configuration change to your application that was not mandatory on earlier versions, but is in newer versions. These changes are typically safe, recommended and easy to implement.

-

From an enterprise perspective - Device Management. Device administration is supported in Android from Froyo onwards - which is pretty much every device on the market. Enterprises may wish to further ‘lock down’ devices to provide a further level of security on corporate devices. New features were added to this API in Honeycomb, so if your company has lots of pre-Honeycomb devices, be aware that they are more open to exploitation.

Following security developments in the Android community and documented security best practices will limit exposure to vulnerabilities. If your requirements determine security to be a Very Important Thing (such as if you are handling sensitive information or money), consider hiring a penetration tester. There’s a cost associated with good security and the fragmented nature of Android certainly increases this cost.

Conclusion

Fragmentation is a feature with bugs. There is a wealth of support available to handle Android’s fragmented nature, some of which is built-in to the framework. External solutions, such as the Android Support Library, are also available to speed up development within this environment and helps apps behave consistently. When fragmentation issues do pop up, a tailored cost-benefit analysis approach must be taken to ensure that the right decision is taken. Factor into analyses the time involved to fix an issue, versus the amount of affected devices and the impact of the fix.

Android embraces fragmentation. You should too! A more open operating system results in more innovation and a wide uptake of devices. Embracing fragmentation means your application is ready to handle whatever device the market produces, and works to a high degree of quality. Maximising the amount of devices your application is compatible with ensures you are well-placed in an increasingly lucrative marketplace.