Over the past year, I worked on a large project which saw a dramatic shift towards a more Agile way of working. In this post, I will run through exactly what changed, how it made our project better, and what you can do to become more Agile.

In the beginning

Our previous process used a lot of the common Agile tools. We worked in sprints, estimated our tasks, held standups, implemented the work, then held a retrospective at the end.

Our retrospectives consisted of our Project Lead talking us through the work over the previous sprint, covering the larger issues we had encountered and the work we had done. We finished each retrospective with the Project Lead asking “does anybody have anything else to add?”, although it was rare for anyone to speak up.

During the sprint, we estimated tasks in days and hours depending on how many “developer-hours” we had that fortnight, taking into account team size and upcoming holidays. When work was done, we would log hours against the task and chart the remaining time as a burndown chart.

A lot of our work was centred around “Pet projects”. These would be sub-projects within the main product development and were the result of requirements capture from the Product Owner. These tasks were assigned directly to team members, and were planned as taking half the allotted time for each sprint, with the other half being spent on main feature development.

The Retrospective

Our team was distributed across multiple offices so communication was more difficult than we’d have liked. To help with this, we ran annual “All-hands days” to get everyone on the project (developers, marketing, UX, website, etc.) in the same place at the same time to discuss the previous year and look ahead to the next. Small workshops allowed us to gather ideas for improvements, which were then collated and presented to the lead developers. In effect, we had a retrospective.

One point raised during the discussions was that the process we had been working with could be improved. We had been using the process for a while, but we had stopped evolving the process, and felt it was not as Agile as it could be.

It was suggested that we should change the format of our fortnightly retrospectives to encourage more developer participation and take the focus away from the project lead. To do this we started simple: each developer brought one “Good thing” and one “Thing to improve” to the retrospective and read them out. We soon saw a few issues bubbling to the surface, and were able to list actions to take over the next sprint.

These actions were clearly actionable and verifiable. We avoided actions such as “Do more reviews” in favour of actions such as “Don’t pick up a new task until your review backlog is cleared”. By doing so, we were able to check at the start of each retrospective whether the actions from the previous retrospective had been completed successfully, and if not, we could ask why.

Getting it ‘Done’

We introduced a formalised “Definition of Done”, where work was only considered “Done” when it was reviewed, tested, and approved by the Product Owner. To reflect this, we changed our burndown chart to plot Story Points instead of time - a story would only ‘burn-down’ when it reached the “Done” column.

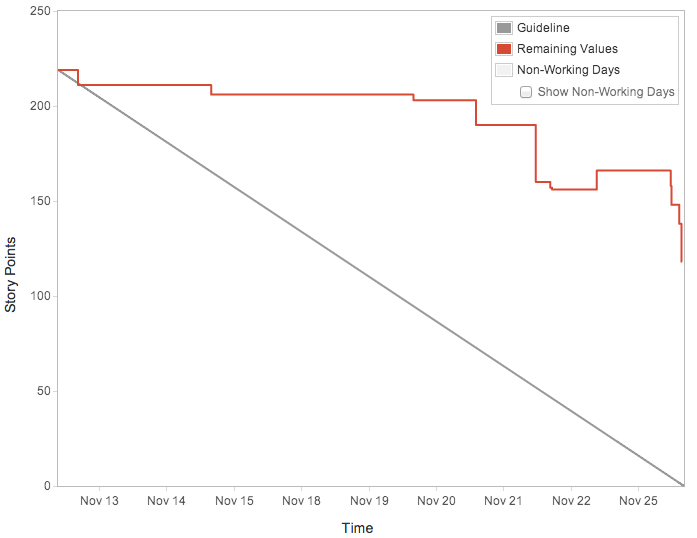

The following burndown chart from before this shift shows how the burndown would have looked, had we been using story points. Because the in-review issue was not as apparent before the end of the sprint, we were unable to get everything through review in the last section of the sprint, and so didn’t get everything “Done”.

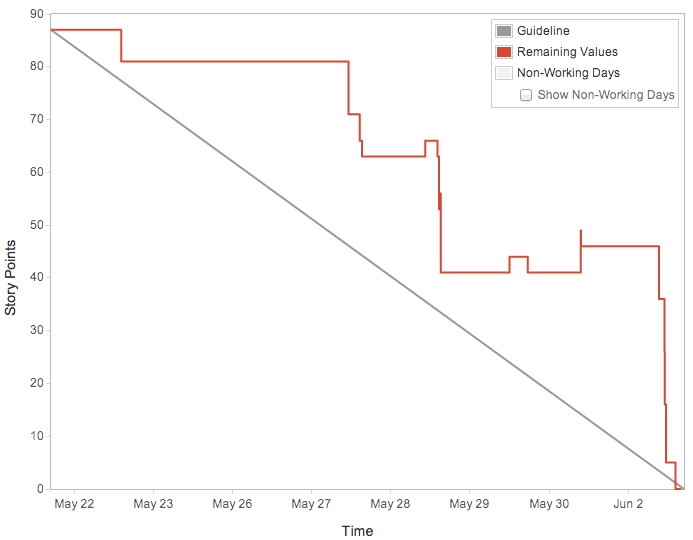

After changing to plotting Story points, it became more apparent when reviews weren’t completed. A good burndown chart is one where the line follows a gradual downwards trend, following the guide line as closely as possible and reaching 0 by the end of the sprint. The chart below shows this much more than before, with issues being completed much earlier in the sprint and following the guideline more closely.

The new view of our sprint-in-progress focused us on completing stories as opposed to getting them to review, cutting the churn dramatically.

Focus Point

We very quickly found that having multiple streams of work was causing problems, both for development and review. Time was split between main development of features, and investigation of “pet projects”, assigned to us by the project lead. It was common for a sole developer to be responsible for developing a single feature, whilst also being the only developer on a “pet project”.

An early retrospective highlighted this issue, and the idea of pet projects were dropped. The tasks were turned into stories or epics, put onto the backlog, and prioritised. Instead, we limited the team to one or two streams of work.

The benefit of this was immediate; design discussions were much more informed between members of a team, and we were able to do faster code reviews within the team as more developers were up to speed and dependent on each other’s features being finished.

Better Together

Soon after we condensed down to one or two streams of work, another retrospective finished with an action to “Do more pair programming”. While this was quite vague (we should have said “Spend at least 20% of our time doing pair programming” to be actionable and verifiable), it allowed us to focus on the fact that we were doing almost no pair programming at all. The action had the immediate positive effect of giving the coder a second pair of eyes to spot issues at the earliest stage, as well as encouraging more discussion about design and implementation.

As a result, we caught more of the minor issues that normally came up in code reviews such as typos or design patterns, so the tasks moved through the “In review” stage much quicker.

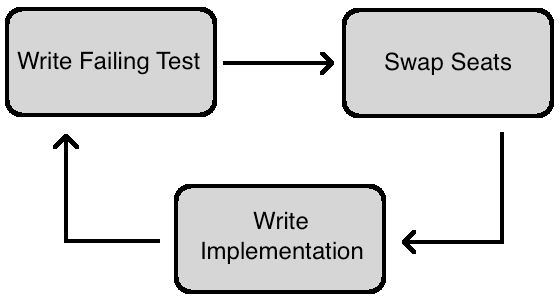

Although we didn’t mandate it at the time, we could have further improved our pair programming by introducing “Testing Tennis”. This form of pair programming has one developer writing a failing test, then passing over the keyboard to have the other developer write the minimal implementation to pass the test, followed by a new failing test before passing the keyboard back.

This keeps from having one developer “driving” for too long, as well as introducing some competitive fun. The tests tend to be more robust, as you actively try to poke holes in the code, instead of just treading the “happy path”.

Onwards and Upwards

The changes to the team didn’t stop after these points. Being Agile means constantly changing and evolving. New ideas come in, and old or outdated ideas are phased out. The most important thing is that the team believes that it is worthwhile to change. We had the desire for an Agile process from within the team as well as from the top, which made it much easier to bring in.

Had it been imposed on the team without them wanting it, there could have been quiet rebellion or undermining of the principles, where the team does what it wants while appearing to those above to be Agile. Likewise, if we wanted as a team to be Agile but management did not, we would have to appear to be doing all the processes they wanted while trying to introduce our own. This would undoubtedly mean that some processes couldn’t be introduced.

We picked a number of standard Agile processes, but not every process will be suitable for every project. Agile is a toolbox, and you need to pick the right tool for the job. It can help to introduce a number of new processes to begin with, before iteratively introducing new processes and removing redundant ones. The important thing is to keep evolving the process, discovering what works best for you.

Tom