When it comes to automated UI checking, there are a complex variety of tools at the disposal of the Tester; including Technologies, Test Runners, Test Frameworks, Cloud Services, Reporters, and CI Systems. While the project itself may dictate a small selection of the combination above, choosing the remainder and getting them to play nicely can be a time consuming task.

WebdriverIO is a Node.JS webdriver library and test runner designed to simplify the testing process, with support for the most popular test frameworks, cloud services, CI Systems, and Reporters out the box - for more info see WebdriverIO’s Getting Started Page (and here for a [loosely] relevant xckd).

This blog post is written in an attempt to guide a new user through setting up WebdriverIO, automating the test workflow with gulp, and then expanding the tests to incorporate the page object model.

The final product will see WebdriverIO set up using Mocha and Chai as the test framework and assertion library, respectively, with the full project accessible here. All tests will be executed on a local Selenium server, with Gulp used to launch the server, run the test runner, and then kill the server afterwards(to keep things tidy), using an npm script command.

Getting Started:

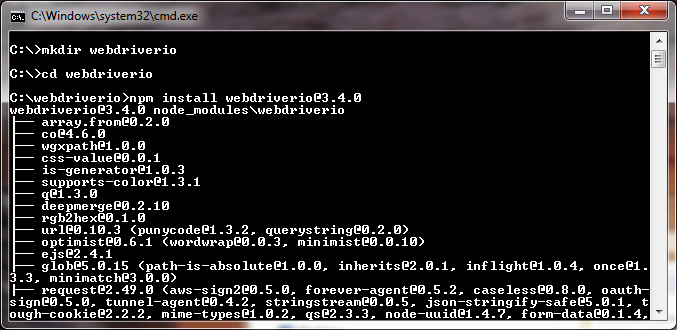

Diving straight in, the first thing we need to do is create a directory for the entire testing library to live in, and install WebdriverIO itself. We’ll be working with v3.4.0, which can be specified with npm install webdriverio@3.4.0 (we’re installing to the current directory, if we wanted to install globally we’d append with –g, npm install webdriverio@3.4.0 –g):

The once empty directory should now contain one new folder, node_modules, which will contain all the npm dependencies.

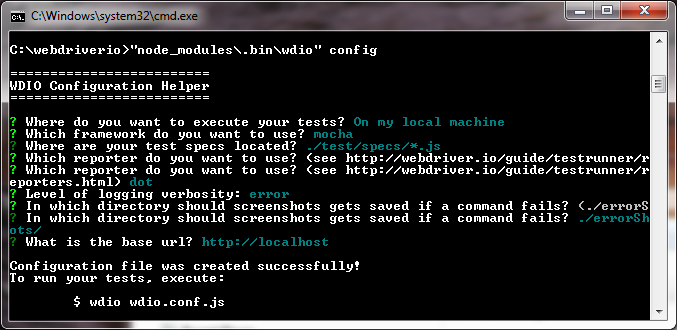

The WebdriverIO provided test runner, wdio, executes all commands synchronously and handles session management very well, so we’ll be using this to execute the test suite (more info here). For wdio to run, it needs a configuration file, which is essentially an object that specifies the location of test scripts/specs, the framework, reporter, and some of our hooks. Luckily, WebdriverIO comes with a handy command line helper to set up the config file, this can be accessed by running wdio config:

//./wdio.conf.js

exports.config = {

specs: [

'./test/specs/*.js'

],

exclude: [

],

capabilities: [{

browserName: 'firefox'

}],

logLevel: 'error',

coloredLogs: true,

screenshotPath: './errorShots/',

baseUrl: 'http://localhost',

waitforTimeout: 10000,

framework: 'mocha',

reporter: 'dot',

mochaOpts: {

ui: 'bdd'

},

onPrepare: function() {

// do something

},

before: function() {

// do something

},

after: function(failures, pid) {

// do something

},

onComplete: function() {

// do something

}

};

We’ve had to point directly to the ‘wdio’ command which resides in the node_modules folder, rather than being able to call wdio itself. This is a consequence of installing locally (the wdio command hasn’t been added to PATH), but this won’t be a problem once we set up Gulp.

You can either set up your config file by running the config helper from your newly created test directory, or create your own wdio.conf.js in the root of your test directory and copy the above code into it. The main points to take away are that we now have a config file in the root of our test directory, which specifies that we’ll be running our tests on the local machine (using a local selenium server, as opposed to Saucelabs etc.), we’ll be using Mocha as our testing framework, and the location of the test specs relative to the location of the config file.

Next up, we need a test/spec file for wdio to execute, which should be in the directory location referenced in the config file:

//”./test/specs/spec.js”

describe("First Spec", function() {

it("should navigate to the WebdriverIO homepage", function(){

return browser.url("http://webdriver.io/")

.click("[href='/guide.html']")

.getUrl().then(function(url){

console.log(url) // outputs "http://webdriver.io/guide.html"

});

});

}) ;

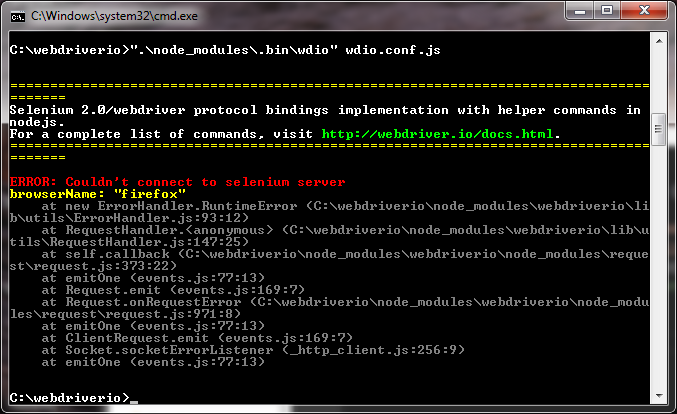

With that set up, we can run wdio providing it with the config file:

That’s good, no WebdriverIO specific errors have fired, and it has found our config file and tests/specs. The next step is to deal with the rather obvious “ERROR: Couldn’t connect to selenium server”, and fix up a connection to the local selenium server.

Setting up the Selenium Server:

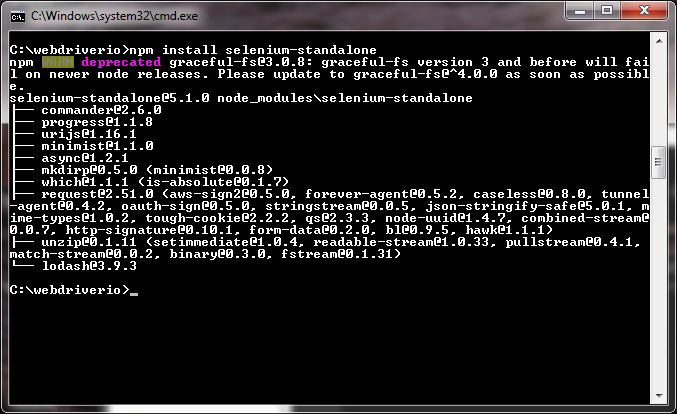

Here we’ll be using the Selenium-Standalone npm package. This package allows us to install the selenium server binary, browser drivers, and the ability to launch a selenium server all from the command line (and programmatically, which will come in handy later), clever right? This can be installed alongside WebdriverIO, using npm install selenium-standalone:

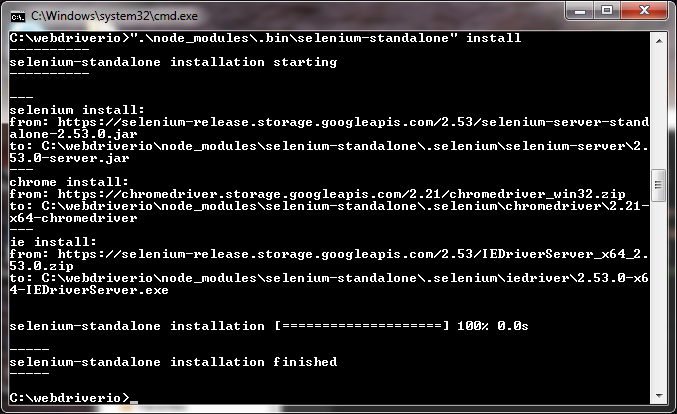

And following that, run selenium-standalone’s install command with ".\node_modules\.bin\selenium-standalone" install:

This command pulls in the latest selenium server version, as well as the default versions of each browser-driver. You can specify exactly which drivers and versions you want to install using variations of the following command (See the npm page for more info):

selenium-standalone install --drivers.chrome.version=2.15 --drivers.chrome.baseURL=https://chromedriver.storage.googleapis.com

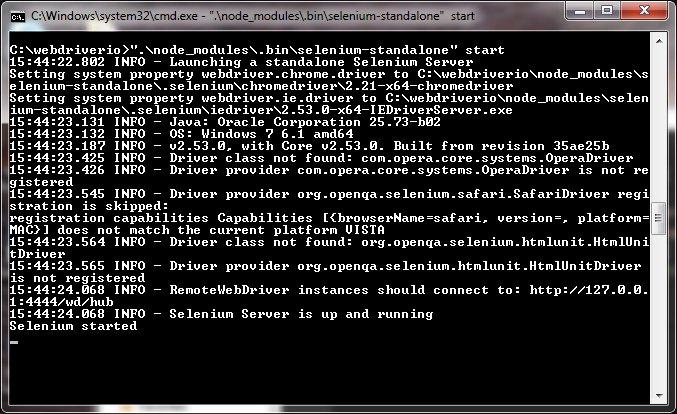

But we’ll stick with the defaults now, following which, we should be able to launch a server using ".\node_modules\.bin\selenium-standalone" start:

The Selenium server remains registered to the command window, so after launching a new one and returning to the test directory, we can try to a test run!

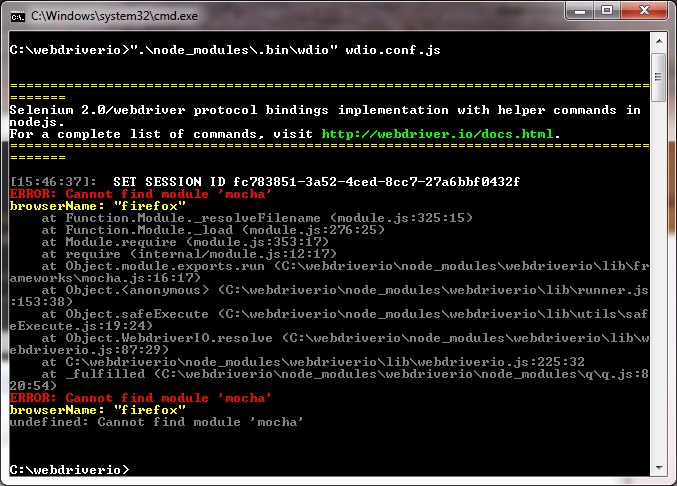

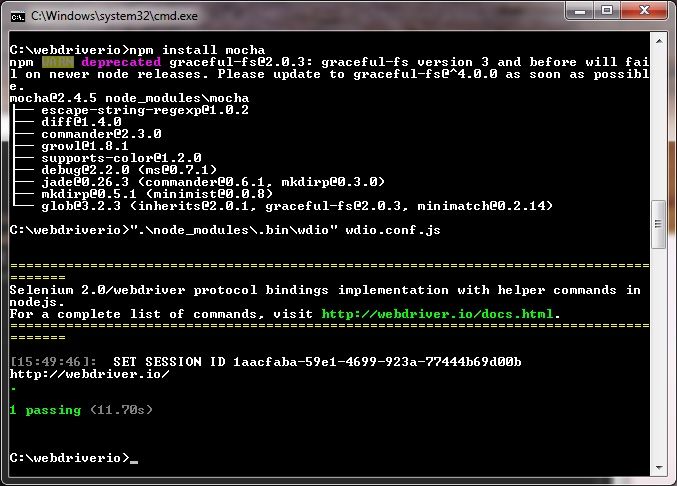

…almost. There’s one last thing we need to do. As we’re using mocha as a test framework, we need to install this as a dependency too. After simply running npm install mocha:

Sweet, one running and passing UI test. Okay, so I guess that was the pretty long version of ‘Getting Started’, but we’ve covered all the basics and developed a solid foundation. Although, having to point directly to the wdio command and manually launch the selenium server when we want to run a test is a bit of a pain; so, let’s make it a bit easier to run our specs by automating the automation!

Setting up Gulp:

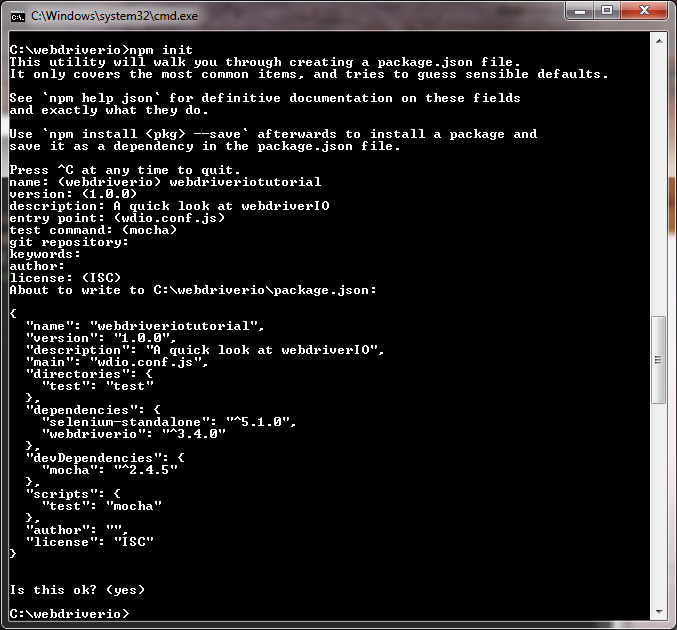

We’re going to take a slight detour and first set up a package.json file so npm can recognise our directory as a package(allowing us to use the npm run command later!). Npm can create one for us by using npm init, which will make assumptions based on the existing directory, and create a package.json from it. Running this in the root of the test directory should give us a package.json that matches the following:

With that done, gulp can be installed locally with the following command:

npm install gulp --save

Appending the command with “—save” tells npm to add gulp to the list of dependencies in the package.json file.

Another package that will help us is gulp-webdriver v1.0.3 (to be compatible with WebdriverIO v3.4.0), from the WebdriverIO team. This package allows us to easily access the WebdriverIO test runner via gulp.

npm install gulp-webdriver@1.0.3 –-save

With gulp, Selenium-Standalone, and gulp-webdriver installed, we now have all the dependencies required to automate the test workflow. This is what we’re building:

//./gulpfile.js

var path = require('path');

var gulp = require('gulp');

var selenium = require('selenium-standalone');

var webdriver = require('gulp-webdriver');

gulp.task('selenium', function (done) {

selenium.install({

logger: function (message) { }

}, function(err){

if(err) return done(err);

selenium.start(function (err, child) {

if (err) return done(err);

selenium.child = child;

done();

});

});

});

gulp.task('runTest', ['selenium'], function() {

return gulp.src(path.join(__dirname, 'wdio.conf.js'))

.pipe(webdriver()).once('end', function() {

selenium.child.kill();

});

});

Which is the ‘gulpfile.js’, where the gulp processes are defined. This is located next to the wdio config file, in the root of our test directory.

We first load all our gulp dependencies:

var path = require('path');

var gulp = require('gulp');

var selenium = require('selenium-standalone');

var webdriver = require('gulp-webdriver');]

And then declare the first gulp task we’ll need, selenium, which follows the structure:

gulp.task(name [, deps, fn])

Where we give the task a name, declare the task’s dependencies (our Selenium task has no other dependencies), and then a function that performs the task’s main processes. Generally, the options for these main processes are outlined on the plugin’s github/npm page (see here for selenium-standalone’s options). Our Selenium task comprised of two; selenium.install() and selenium.start():

//.gulpfile.js

...

gulp.task('selenium', function (done) {

selenium.install(function(err){

if(err) return done(err);

selenium.start(function (err, child) {

if (err) return done(err);

selenium.child = child;

done();

});

});

});

...

Both commands can take an options object before the callback, but we want to run with the default options, so we provide only the callback functions.

Looking inside the selenium.start callback, we set the selenium child process on to the selenium object so it can be shut down later.

Our second Gulp task is going to run the wdio command, executing our tests:

//./gulpfile.js

...

gulp.task('runTest', ['selenium'], function() {

return gulp.src(path.join(__dirname, 'wdio.conf.js'))

.pipe(webdriver()).once('end', function() {

selenium.child.kill();

});

});

...

Following the same setup as before, we’ve named this task ‘runTest’, declared our previous Selenium task as a dependency, and then defined the main operations for the task. Simply, gulp.src obtains the file located at the provided file location/glob, which can then be piped to the chained process. We’re piping the config file into the gulp-webdriver process, webdriver(), which is the equivalent of running wdio wdio.conf.js in the command line. It is possible to provide gulp-webdriver with config options at this stage, such as:

.pipe(webdriver({ logLevel: 'verbose',

waitforTimeout: 10000,

reporter: 'spec' })

However, it is much more maintainable to contain these in the external config file (further info on gulp-webdriver and available options can be found here - Getting-started and gulp-webdriver).

The final thing we need to do before running is set up an npm run script so we can access our newly created gulp tasks from the command line. We could run them via gulp runTasks, but as we only have Gulp installed locally we would have to point directly to the gulp command in our node_modules e.g. “./node_modules/.bin/gulp” runTasks, and using npm scripts is a much cleaner and easier method.

Setting up the npm run task is super simple, and can be done via the project.json file. init should have been kind enough to set up a “Scripts” attribute. In here we can define our gulp task:

//./package.json

…

},

"devDependencies": {

"mocha": "^2.4.5"

},

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha",

"runTest": "gulp runTest"

},

"author": "",

…

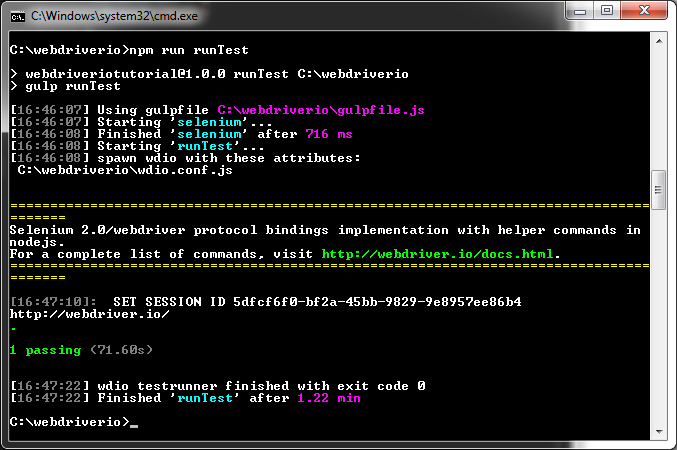

From here, all we need to do is execute npm run runTasks to access the assigned gulp workflow. This works because the npm run command adds node_modules/.bin, our local dependency directory, to the shell’s PATH, allowing us to run Gulp like it’s installed globally!

That’s it for setting up our workflow environment! Without gulp, each time the test were to run we’d need to (perhaps update) launch our selenium server, run our test scripts, and then kill the server. With it, we’ve automated this workflow, allowing us to run it all with one simple npm command.

Continue on to part 2 for a guide to setting up tests and developing them in more maintainable way using the page-object model.