When we think of Interfaces, we often imagine some sort of device or application. An interface does not have to be limited to an object. It is a point of communication between two systems, whether they are objects or living beings. Certain iPhones support User TouchID that allow you to unlock the phone by placing your thumb on a biometric reader. The biometric reader acts as an interface. I could argue that the thumb is an interface as well.

We use our body as an interface every day without even noticing it. Think about how often you walk into a room and lights turn on because of a sensor detecting your movement, or how often you walk through automatic doors that open when you get closer to them. You might have used sound activated lights that turn on when you clap your hands. Some of us may even remember their first light up LED shoes that lit up every time we took a step.

In my opinion, there are two categories in which the body is used as an interface: the first one is within a controlled environment. The second one is when the device becomes part of the body.

In the first category, users do not need to hold any devices, but need to be in a specific location that has been set up to allow them to use their body as an interface. Their location is known, and the designer controls the space within which they interact. These conditions lend themselves to a curated type of interaction, commonly found in interactive art installations. The video gaming industry brought this type of interaction to the mainstream with products like the Kinect.

In the second category, the device remains unintrusive and seamless. Users can wear it in any location and are able to move freely. Examples in this category are found in wearable technology. Devices like bluetooth headsets, Google Glass, or Fitbit become part or an extension of the body.

Some products like the Wii Remote or Microsoft’s HoloLens fall under both categories. Users need to hold a device and be in a specific location in order to use their body as an interface.

BODY AS INTERFACE IN CONTROLLED ENVIRONMENTS

Within the art field, the notion of the body as an interface is not a new idea, but one that artists have been experimenting with for a while.

In 1999, Camille Utterback created Text rain, an interactive installation in which participants use their body to interact with words of a poem. Participants stand in front of a screen where letters are dropping like rain. A camera detects where they are standing and allows them to virtually catch those words on the screen. Participants only need to stand to interact with the letter, but the letters also respond to their body motions.

“Text Rain”, Camille Utterback.

A similar project is Body paint by Mehmet Akten. The interactive art installation allows people to paint on a virtual canvas with their body. The paint reflects the movement of their body and the direction in which they move.

In both examples, the body is used to interact with visuals on a screen. The artists designed where users would stand. They set up the environment for them and controlled the lighting. They presented their projects in art galleries or museums where Users are open to experimenting with this type of interactivity. Body movement is not the only trigger for this type of interaction. Biometrics have also been used for that.

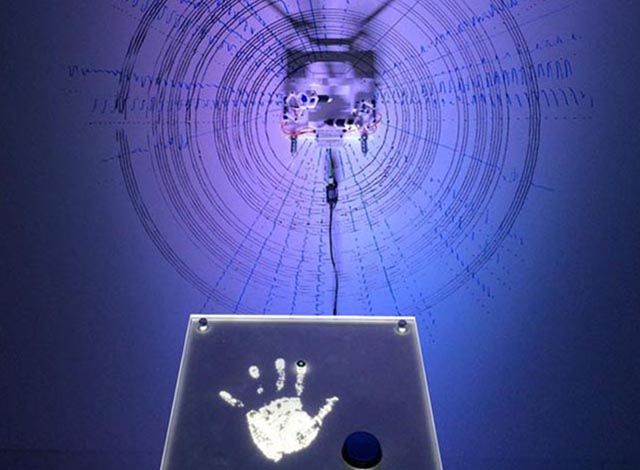

The Heart Bot is an experimental biometric installation in which a drawing machine allows people to draw on a canvas using their heart rate. Users place their hand on a sensor that reads their heart rate. A mechanical tool draws the pattern created on a paper mounted on the wall in front of them. Through this process, the collected heart rate data from users is translated into art.

“Heart Bot”, Commissioned by Sid Lee for Intel x SMS audio collaboration.

With the Heart Bot, biometrics are used to initiate the interaction. The artist not only controls the environment, but also guides the interaction with a drawing of a hand. The hand print specifies exactly what part of the body the artist expects of participants to use, and where they would place it. Similar to Text Rain and Body Paint, people do not need to carry any device and can use their body as an interface in the exhibition space.

DEVICE BECOMES PART OF THE BODY

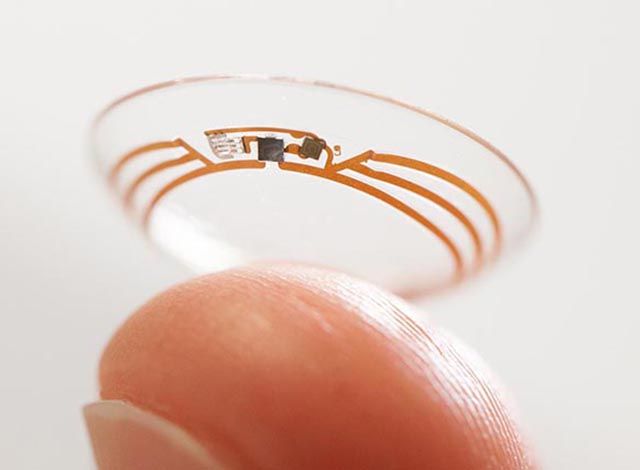

In wearable technology, devices become integrated into our clothes, or take the shape of accessories we wear. Products like bluetooth headsets, smartwatches, Google Glass, and Virtual Reality goggles augment our bodies. Some of these devices are almost invisible. Smart contact lenses are an example of that. Tech companies have started showing an interest in it. Google is designing a contact lens that allows diabetic patients to monitor the level of glucose in their body. Samsung is contemplating designing augmented reality contact lenses. Most wearable devices try not to obstruct any of our usual interactions or movements. They become part of our body.

In some cases these technologies go a step further and alter the way we use and experience our body. They reveal to us information about ourselves that we otherwise would not have had access to. We see a rise in the adoption of fitness trackers that track location, number of steps taken, sleep patterns, heart rate etc. These monitors allow us to analyse our behaviours and set goals to alter them.

Products like Microsoft’s HoloLens and the Oculus headset alter our vision. They extend the screen to the space around us and change our vision, even if only temporarily while we are wearing the device.

CREATING ALTERNATIVE EXPERIENCES

Wearable devices can alter the way we experience the space around us. When the body is thought of as an interface, designers start adapting the device to the body rather than expecting users to adapt to the device. This is very powerful when applied to sectors like healthcare. We started seeing its benefits with fitness trackers and smart lenses. Another example would be the Eyewriter.

The Eyewriter is a low cost eye tracker system. It was designed for American graffiti artist Tempt One who was diagnosed with degenerative nerve disorder ALS in 2003, which left him fully paralysed except for his eye movement. Eyewriter tracks the movement of the eye to allow ALS patients to draw using their eye movement.

“Eyewriter”, Tempt1, Evan Roth, Chris Sugrue, Zach Lieberman,Theo Watson and James Powderly.

These projects and devices have in common the ability to create alternative experiences. They leverage the body as an interface to do that. When we start thinking of the body as an interface, we stop designing interfaces and we start designing experiences. This allows us to leverage the body to design experiences that adapt to users’ interactions rather than force users to adapt their interactions to the device.