This is the second blog post orientated around Bitcoin and its inner workings. The first post took the blockchain and broke down the algorithms which create the fundamental structure of any cryptocurrency. The post was separated into two sections; the first focusing on the block header and the second focusing on the construction of a transaction. If you are not comfortable with how the blockchain works, I suggest you read the first blog post before continuing.

Recently there has been much discussion, or rather argument, over the block size limit in bitcoin. A change to the block size limit could not be achieved without a hard fork of the network, and without nearly all active nodes adopting the new fork, the network may fracture into multiple altcoins. There are many arguments for and against, but the key arguments for are that more transactions can occur per second and off-chain solutions are currently not in a position to take the load off the main blockchain. The off-chain solution of the lightning network is the focus of this blog post, in particular how Hash Time-Lock Channels are formed offline between nodes.

In particular, the following post looks at transaction types, with a goal of creating a transaction channel which can be implemented in an off-chain, trustless channel between multiple parties. Once again, we will use the cryptocurrency bitcoin when illustrating theory with examples. In all situations described in this blog, we want everything to be a completely trustless model, where everything can be cryptographically proven and no one is trusted with any of the money they hold.

Simple Transactions

Let’s recap how transactions work quickly. Firstly, outputs from previous transactions, which the sender owns, are identified. The amount of bitcoin located at each output is checked and more previous outputs are pulled in until the sender has enough money for their desired transaction. The list of previous outputs is then added to the transaction, each identified by using the previous transaction hash and output index. A stub value of #ffffffff is added to each input. The sender then requests an address from the recipient to which money can be sent to. Rather than receiving an address, the sender receives a scriptPubKey (a focus of this post). The scriptPubKey is a simple stack of commands which when popped and evaluated determine whether money at these addresses can be spent. The amount of bitcoin to be sent to each output is then added. The sender now has a set of inputs and outputs. They populate the remaining values before signing each input and submitting the transaction for approval on the network; nVersion, inputCount, outputCount and blockLockTime (also referred to as nLockTime).

So now we are comfortable with a simple transaction, we can play about with the scriptPubKey to create some interesting redeem conditions. Here are some common scripts and the associated signatures which are used to redeem the transaction is possible.

Pay-To-PubKey-Hash Output;

scriptPubKey: OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

scriptSig: <sig> <pubKey>

Provably Unspendable Outputs;

scriptPubKey: OP_RETURN

scriptSig: -

Anyone-Can-Spend Outputs;

scriptPubKey: -

scriptSig: OP_TRUE

Multi-Sig Output;

scriptPubKey: OP_2 <pubKeyA> <pubKeyB> OP_2 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

scriptSig: <scriptSigB> <scriptSigA>

In order to better understand how the stack operations work, here is a worked example of a Pay-To-PubKey-Hash script which has a valid signature provided.

1. An input will reference an existing output, and the scriptPubKey is taken

from that old output:

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

2. The input then contains a scriptSig used to redeem the coins at the address

contained within the scriptPubKey:

<sig> <pubKey>

3. The scriptSig and scriptPubKey are appended together on a stack and each item

is popped and transferred to a processing stack. The check stack is shown below

and at each stage the leftmost item is removed and processed. The state of the

processing stack is shown below each operation.

<sig> <pubKey> OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

STEP 1 : Pop the first item of the Check Stack into the Processing Stack.

<sig>

STEP 2 : Pop the first item of the Check Stack into the Processing Stack.

<pubKey> <sig>

STEP 3 : Apply the duplicate operator to the top of the Processing Stack.

<pubKey> <pubKey> <sig>

STEP 4 : Apply the hash160 operator [Sha160(Sha256(<pubKey>))].

hash160(<pubKey>) <pubKey> <sig>

STEP 5 : <pubKeyHash> is popped onto the Processing Stack.

<pubKeyHash> hash160(<pubKey>) <pubKey> <sig>

STEP 6 : <pubKeyHash> and hash160(<pubKey>) are checked for equality

according to OP_EQUALVERIFY. If the result is true, continue.

<pubKey> <sig>

STEP 7 : Compare <pubKey> and <sig> according to OP_CHECKSIG. If the result

is true, the <pubKey> and <sig> are popped from the stack.

-

STEP 8 : If once the output script has been executed the stack is empty,

bitcoin interprets this as a valid execution of the stack.

-

Time-Lock Channels

The last blog post did not go into the nLockTime in large amounts of detail. Lets look at what we can achieve through playing with the nLockTime. It is used to determine how long a spender must wait after the inputs were created before the transaction they have created can go live. A value below 500000000 is treated as a block height (the transaction is locked in this block) and a value equal or larger is treated as a UNIX timestamp.

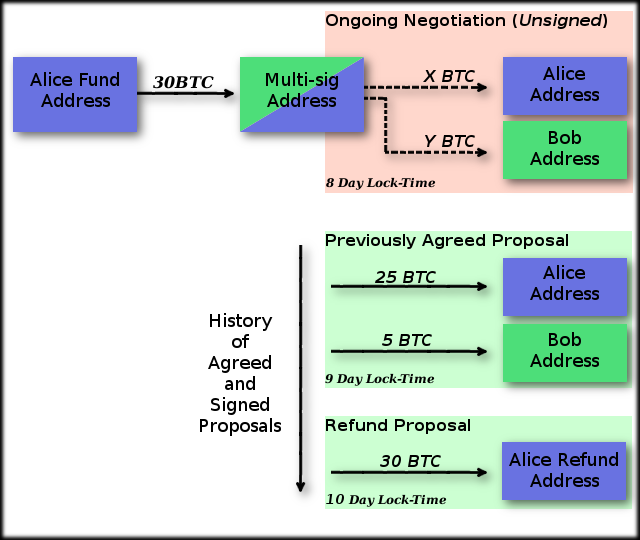

So what is the benefit of delaying a transaction from becoming live once it has been created? A common example where this is beneficial is when there is some uncertainty about the transaction output. Given the situation where Alice wants to send Bob some money but is unsure of exactly how much, Alice can create three transactions (with a little help from Bob). The first transaction has inputs from Alice to an address owned by both Bob and Alice. This is a Multi-Sig address and this transaction is funding this joint address. Let’s say the address is funded with 30BTC. The second takes coins sat at the multi-sig address and sends them to Alice and Bob. The third takes the coins at the multi-sig address and sends them back to Alice. This is a refund transaction of all 30BTC sat in the multi-sig address. Transactions two and three are multi-sig transactions which must be signed by both Bob and Alice in order to be valid. Here is a diagram for the Time-Lock Contract we have just described and will be building a new type of transaction channel around. The multi-sig address funding (transaction 1) is not broadcast until Bob has co-signed Alice’s refund transaction.

Below is a pseudocode algorithm for creating these two transactions, note that unless stated, all contents of the transactions are kept local to the person who created it. In the example below, Alice and Bob have 10 days to agree on final payments before Alice can refund her money located in the multi-sig account. 10 days has been chosen in this example as a nice, round value to work with. In actual fact these numbers may be much smaller or larger depending upon the reason for the channel’s existence. So long as numbers are chosen which will give participants enough time to perform negotiations without suffering from race conditions, values can be as small as users wish. The limit on the value is the length of time you wish all negotiations to have finished by, this may be years or decades ahead of time. If the value is too large the participants of the channel may no longer be alive to claim the bitcoins, making it fairly foolish to have a nLockTime this far into the future.

1. Alice and Bob create a multi-sig address.

2. Alice creates a transaction which sends 30 coins to the multi-sig

address, signs it, and calculates the transaction hash. This

transaction is stored privately by Alice.

3. Using the previously created multi-sig address, Alice creates a

transaction which takes all coins from the multi-sig address and

sends it back to another address Alice owns. The transaction has

a nLockTime value for 10 days in the future.

4. Alice signs this transaction and sends it to Bob.

5. Bob signs the transaction and sends the signatures he made back

to Alice.

6. Alice saves this transaction. This is her refund transaction.

7. Alice broadcasts the transaction she saved privately in step 2.

Money is now sat in the multi-sig address and Alice can claim

a refund on it in 10 days unless it is spent in another transaction.

8. Alice and Bob can now create a transaction spending the coins

located at the multi-sig address. When a transaction has been signed

by both parties and broadcast, the refund transaction will become

invalid.

The nLockTime value for this transaction is 9 days initially.

Each time a new set of outputs is proposed, whoever proposes

the transaction signs it. If the other party agrees to the outputs

they can sign it also and then broadcast it. Each agreed upon proposal

should use a nLockTime which is slightly smaller than the last. This

will allow the most recently agreed transaction to be broadcast and

invalidate any older agreements.

This collection of transactions can be called a unidirectional channel. The two members can barter and propose who gets how much of Alice’s money and if no decision is reached within 30 days, Alice will receive her money again. This could become a bidirectional channel if Bob was to also pay money into the multi-sig address and generate a refund transaction using the multi-sig address in the same manner Alice did.

We now have a structure which allows an exchange of coins to be debated by multiple parties and refunded after a timeout occurs. This idea can be expanded to allow money to move over N parties en route to its destination. We could now describe this transfer over all parties as a channel, more specifically a Time-Lock Channel as the channel has a timeout which will result in a channel closure. A practical use of this N party bartering system would be in compiling many micropayments into a single transaction. Over the course of however many days, banks could create a channel with the client, and as multiple micropayments come in, the channel will continuously update the payment between the client and the bank. As the client spends more and more money on microtransactions, the bank adjusts the balance of funds paid to itself and back into a client’s account. If at any point, the client or bank disputes the most recent payment, a previously agreed and signed transaction exists which they can fall back to.

Unfortunately, when we expand this approach over more than two parties, we begin to require an element of trust with the middlemen, and even the recipient of the transaction. Bitcoins may be sent to the recipient through a third party, who claims to be paying the recipient, but is actually keeping the money for themselves. At this point the recipient tells the sender they are not getting money. How does the sender know where the flow of bitcoins in the channel is being blocked? The inherent problems we see when sending normal transactions between multiple parties remain when third parties are involved, such as denying that money was ever received. We aim to find a method to transfer money between these third parties which requires absolutely no trust and is cryptographically secure.

Hash-Lock Channels

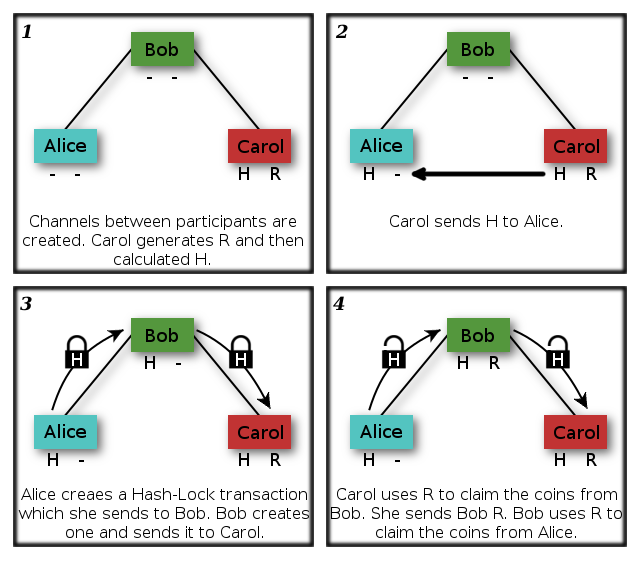

A step towards a solution of off-chain secure payment channels is to look at Hash-Lock Channels. These are contracts where a hash output (H) is used to create the contract, and the only way money can be redeemed is through providing the hash’s raw input data (R). The recipient generates R and keeps it hidden from the rest of the network and shares H at no risk to R since hash functions cannot currently be reversed. When the recipient uses R to redeem their coins they propagate R through the channel back to the sender. As each member of the channel is able to redeem their coins using R, it can be shown to the redeeming member that the recipient has received their due coins. This is because R could have only been found if the recipient announces it, and R will only be announced once the recipient has received their coins.

If the recipient generates the raw data, the hash, and provided other members of the channel with the hash, they will be able to redeem the final transaction to them from anyone in the chain.

Once they have redeemed the transaction they provide the raw data down the channel to each participant, allowing each member to redeem money contracted to them. Here is a diagram showing Alice sending money to Carol through Bob.

It is important to note that each transaction is sourced from coins owned by the sender. Coins are not chained through transactions as this is impossible to do when a transaction has not been completely signed. As each new transaction is created up the channel, the scriptPubKey remains almost the same. It is possible for a sender to copy the R component of the key into the new transaction they make.

Issues remain with this approach however. Carol can refuse to disclose R, and if her channel with Bob expires after Bob’s channel with Alice, Carol is able to steal funds from Bob as he is no longer able to take his funds from Alice. This leads onto another issue with this approach. Bob needs to have a large pool of funds in order to handle transactions. If an exchange of 25BTC at the current rate of £300 per bitcoin (£7500) was to move through the channel, Bob would need to be able to part with 25BTC for a short period while he waits to receive R.

Hash Time-Lock Channels

We now introduce the idea of a Hash Time-Lock Channel. This merges the idea proposed by Time-Lock and Hash-Lock into a channel which requires a hash to redeem output, and in doing so acts as a way of confirming receipt of payment, but also has a timeout to prevent the race conditions described above.

Let’s look at how a Hash Time Lock Transaction is created, specifically how coins are redeemed. We will take an output signature along with a valid input signature and process through the stack for some better understanding as to how HTLCs work.

1. An input will reference an existing output, and the script is taken from

that old output. The stack has been formatted for readability:

OP_DEPTH OP_3 OP_EQUAL OP_IF

OP_HASH160 <H> OP_EQUALVERIFY

OP_0 OP_2 <AlicePubKey1> <BobPubKey1> OP_2 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

OP_ELSE

OP_0 OP_2 <AlicePubKey2> <BobPubKey2> OP_2 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

OP_END

2. The input then contains a scriptSig used to redeem the coins at the address

contained within the scriptPubKey. This output can be redeemed with either of

the two signatures:

<R> <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

<BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

3. The scriptSig and scriptPubKey are appended together on a stack and each item

is popped and transfered to a processing stack. The check stack is shown below

and at each stage the left most item is removed and processed. The state of the

processing stack is shown below each operation. Shown in this example is the

evaluation of the first of the two valid signatures.

<R> <AliceSignature1> <BobSignature1> OP_DEPTH OP_3 OP_EQUAL OP_IF OP_HASH160 <H>

OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_0 OP_2 <AlicePubKey1> <BobPubKey1> OP_2 OP_CHECKMULTISIG OP_ELSE

OP_0 OP_2 <AlicePubKey2> <BobPubKey2> OP_2 OP_CHECKMULTISIG OP_END

STEP 1 : Each top item in the check stack is popped into the processing stack

until an opcode is hit.

<R> <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 2 : OP_DEPTH is popped and evaluated, adding the size of the stack to the

top of the processing stack.

3 <R> <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 3 : OP_3 is popped into the processing stack.

3 3 <R> <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 4 : OP_EQUAL is popped. It takes the top two items of the processing stack,

checks if they are equal, and pushes the result back to the stack.

OP_TRUE <R> <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 5 : OP_IF is popped. It pops the top item of the processing stack and checks

if it is true, at which point it enters the first nest in the if/else

clause.

<R> <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 6 : OP_HASH160 is popped. The top value of the processing stack is popped,

hashed and pushed back to the processing stack.

hash160(<R>) <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 7 : <H> is popped into the processing stack.

<H> hash160(<R>) <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 8 : OP_EQUALVERIFY is popped. It takes the top two items of the processing

stack and checks to make sure they are equal. If they are not the

script execution halts and returns failure.

<BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 9 : Each operand is popped from the check stack to the processing stack in

turn until an opcode is hit. OP_X is evaluated to X.

2 <BobPubKey1> <AlicePubKey1> 2 0 <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 10 : OP_CHECKMULTISIG is popped. This pops the first item on the stack and

pops this many other items. These will be read as public keys. It then

pops the next item and due to an indexing error in bitcoin, will pop 1

more than stated signatures. The state of the stack is now empty, but

the multisig is yet to be validated. Below is the state of the multisig.

Public Keys [2] = <BobPubKey1> <AlicePubKey1>

Signatures [2 + err] = 0 <BobSignature1> <AliceSignature1>

STEP 11 : The first signature is taken. Due to the bitcoin off-by-one error the

first signature is ignored and read as <BobSignature1>. This is validated

against each public key until one returns valid. The next signature is

taken and compared to the next public key in the sequence. If any

signatures fail to validate script execution stops and returns a failure.

4. Using the alternate script requires signatures from Alice and Bob but no hash.

The transaction with these signatures has a nLockTime included to prevent instantly

withdrawing funds from the multisig address. This alternate signature is the

refund transaction for Alice in the example below.

This hash time-lock contract can be expanded from two to multiple people safely.

Let’s say Alice wants to pay Carol some money, channeling through Bob. As per the Hash-Lock channel, Carol will generate R and H, sending H to Alice. Alice then creates a transaction which can only be unlocked using R. Alice forwards this transaction to Bob with a nLockTime of 2 days, Bob creates a similar transaction for Carol with a nLockTime of 1 day. In order for Carol to redeem this transaction, she must sign the transaction from Bob with R. In turn each member of an amicable chain would add R to their scriptSig and then forward R to the next member of the chain so they can redeem their coins. Here are some situations which could arise to cause problems in other types of channels but not with HTLC:

Carol signs her transaction and refuses to send R to anyone. In this scenario Carol then has two options, either she waits until her HTLC with Bob expires before broadcasting, or she broadcasts her signed transaction to the blockchain to claim her money. If she waits until the channel expires, Bob will activate his refund and this will halt any exchange of coins between Bob and Carol. If she redeems her money before the channel expires, Bob is able to read the value of R from the broadcast transaction and redeem his money from Carol.

Bob’s node goes offline and cannot be contacted. In this scenario the connection between Carol and Bob may timeout, or Carol can take the money contracted to her from Bob. If Bob has been sharing his working contracts with the network, another member of the network could sign on Bob’s behalf, and send the multisig coins to Bob’s address. A less friendly member of the network may leave Bobs transaction unsigned and use the refund transaction to deny Bob his funds. It is unlikely Bob’s node would be down for a long time, so larger lock times could be used to mitigate this problem.

Reflection

So the whole process of moving towards the creation of Hash Time-Lock Channels involved simply placing an ‘if/else’ statement between a Hash-Lock Channel and a Time-Lock Channel. As with most great ideas, this principle is remarkably simple, it just takes an intuitive mind to spot the solution. The amalgamation of Hash-Locks and Time-Locks leads us to a transaction type which is resistant to receipt fraud in any situation and to missing channel members (if the channel is somewhat amicable). The ability to hold channels open and renegotiate with its members multiple times before the channels close allows many transactions to occur and to be compressed into a single larger transaction. Using numbers provided by Joseph Poon and Thaddeus Dryja in their white paper, with the current approach a network of 7 billion people making 2 blockchain transactions a day produces 24GB blocks (assuming 250 bytes per transaction and 144 blocks each day) and requires 50 Mbit/s node speed. Utilising channels to compress transactions and broadcast out transactions when they are significantly large, could reduce this to 133MB blocks (even when transactions are 500 bytes in size) at 3Mbit/s. The inherent problem of increasing the block size to this extent is that very few nodes will be able to keep up with the network. Full nodes will require machines with much larger storage capacity and much faster internet. It will become much smaller in network and resultantly only a few full nodes will be able to exist. This diverges from bitcoins intent of being a completely decentralised network.

Conclusion

The result of these projections could mean the difference between mainstream international cryptocurrency trading being impractical and practical. A concept certainly worth further investigation, especially as we continue to see a growth in the size of the market. A project started recently called Thunder, which is the first implementation of the Lightning network. Could this be the start of the end of the traditional payment networks?