We’ve recently been investigating uses for the blockchain and as part of this, we’ve developed our own system called Scottcoin which powers our office tuck shop. This post will explore the core components of the Bitcoin system, how a transaction goes through it, how our internal version differs and what advantages and disadvantages it brings.

This post will cover things at a very high level of detail, if you are interested in the “nitty gritty”, check out these other two blog posts: Jenny from the Blockchain and Bitcoin Payments and the Lightning Network.

The Structure of Bitcoin

Bitcoin is primarily made up of 3 main components, transactions, the network and miners.

Transactions are the heart of the system and everything else is made to support them. At the lowest level they contain the information of a transfer of currency from one set of wallets to another. Anyone can write a transaction, as long as they have the private key for the input, but on their own they don’t mean much.

For example: on their own, users could attempt to double spend money or say they have money that they don’t, however this is where the rest of the system comes in. For a transaction to be confirmed as valid it needs to be accepted by the majority of the network.

The network is a peer to peer network made up of a collection of nodes. A node is an instance of bitcoin that connects to other nodes so that it can receive transactions from and publish transactions to the wider network.

Once a node is connected to the network and has downloaded the current blockchain, it can then help to propagate transactions around the network. Firstly it listens for new transactions coming in, if it has seen the transaction before it discards it but if it’s new, it will validate the transaction and then pass it on to all its peers. This viral propagation means that eventually the transaction should reach the majority of nodes (at least once).

If users could constantly submit vast quantities of valid transactions to the network, they would not have enough time to propagate around the network. Without the majority of nodes knowing about transactions, they would not be able to come to a consensus and users would be easily able to double spend their money. Miners, using a concept called proof of work, are the decentralised solution to this tricky problem.

Miners bundle a group of transactions submitted to the network together into a block so that they can be submitted in batches rather than a constant stream, allowing time for them to propagate around the network. A block is only considered valid by the nodes when it contains a piece of work that is very hard to calculate but easy to confirm.

Since it’s hard to calculate the PoW and the solution can only be found by a random search, the miners can be considered to be in a race. In bitcoin, the difficulty varies slowly over time so that the PoW can be solved in roughly 10 minutes.

With these 3 core components, Bitcoin provides a system which lets its users trade openly and securely without requiring a central governing body. The rest of this post will talk through the journey of a transaction in more detail. Not only should this reveal more about how bitcoin itself works but how the general concept can be more widely applied.

The Journey of a Transaction

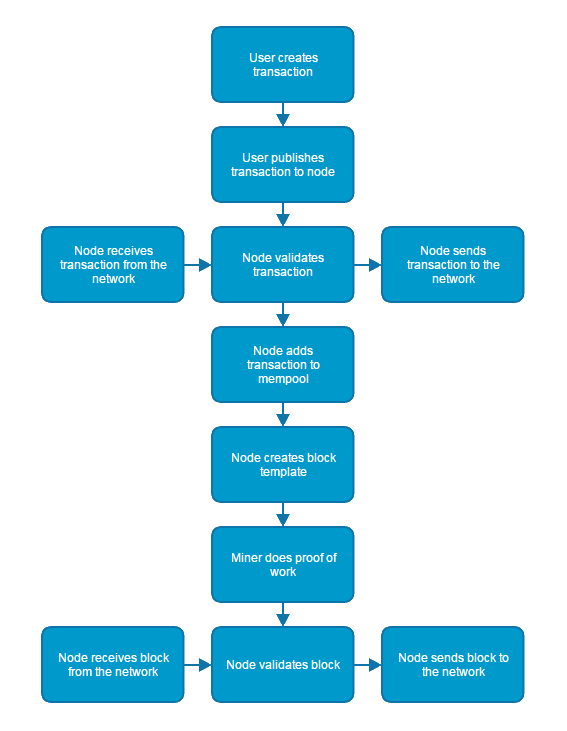

Transactions

When a user creates a transaction, they specify a set of address to source coins from and a set of addresses to which the coins are sent. Against each address, an amount is specified which allows the user to partially spend funds or proportion them across address.

The transaction is first checked by the node it is submitted to, to see if the transaction is valid. This is just a simple check to see that it was made by the owner of the keys to the input addresses and that there are more funds in the input addresses than the output addresses. Once the node has accepted the unconfirmed transaction, it sends it to the network for other nodes to see and adds it to its mempool.

Blocks

Mining nodes in the network may update their block template to include the new transaction if its fee, the difference between the sum of the input amounts and the sum of the output amounts, makes it worth including. If not, they may store it for inclusion in a later block when the transaction volume, and therefore the fees, have decreased.

Theoretically transactions could be mined individually with each referencing the previous transaction to create a transaction chain. However for a large volume of transactions it is more efficient to group them together.

A block is primarily made up of transactions, which are included up to of a preset limit currently fixed at 1MB (normally around 0.75MB or 2,000 transactions). Additionally the block contains, the root of the merkle tree of transaction hashes, the proof of work (PoW) and a reference to the previous valid block.

Since a block has a reference to its preceding block, and that block has a reference to the block before that, this creates a chain of blocks. The “blockchain” records all transactions since the genesis block, producing a “distributed ledger”.

Miners

Miners get the block template from a node which includes the above and adds an additional transaction called the coinbase transaction. The coinbase transaction that the nodes allow to break the rule of requiring input addresses to contain enough coins to be sent to the output and instead allow the input to be anything at all. The value of this transaction is capped at the total of all transaction fees in the block and a value which varies over time but, for now, it acts as an additional incentive for the miner.

The final task is the proof of work which ratifies the block. Once the miner has solved that, it can send the valid block back to the network to be propagated around and for the network to come to a consensus that the block is the next one on the chain.

For a more in-depth discussion on this process, like how the merkle tree is calculated, see here.

How Scottcoin’s different

Bitcoin is decentralised, where anyone can attempt to mine a block and receive a reward for it at the expense of processing power. There is no central governing body that decides the rules of the system e.g. the minimum fee level, the value of the coinbase transaction, etc.. These decisions are instead encoded in the software run by miners. In the case of a disagreement on these values, the version being run by holders of more than 50% of the network’s mining power will triumph.

Whilst this is great for a decentralised system, in our internal version it made more sense to run a “Permissioned blockchain”. In these systems instead of having a computationally expensive proof of work, we use a mining system where mining is restricted to a permissioned set of nodes. This allows us to protect our system from double spending without requiring us to pay for 51% of the computing power.

The signing is done using the same cryptographic primitives already employed by bitcoin. A private key is used to sign blocks and a public key to verify their signatures. When the miner creates a new block, instead of solving a difficult PoW, it signs the block using the private key only it has access to. All nodes in our system have access to the public key via a back channel. This allows them to easily verify that the block was signed by our central system.

To make these changes to the network we only need to change how the miner works, slightly modify how the blocks are serialised to the network and tweak how blocks are validated. We did not need to change anything about how transactions worked.

As discussed, in Bitcoin users can add fees to their transactions. There are multiple reasons for having fees on transactions and one of them is to prevent flooding attacks on the system, another is to incentivise miners to include transactions faster. As our system is closed to outside participation and only expects a very low volume of transaction, we additionally decided to remove the fees.

Why Scottcoin will (won’t) take over the world!

Whilst our system allows us to have all the features we need to run a simple tuck shop, it’s far from perfect.. Fundamentally we’ve taken a system full of the complexity required for running in a decentralised manner and centralised it without removing any of the complexity!

For example, not having a fee doesn’t affect how fast a transaction will be confirmed in our system however it does leave us open to flooding attacks on the system. This is fine for our small system but for a real world system, this wouldn’t be acceptable.

Another problem would occur if the private key were ever to be compromised. As we have our own miner, we can easily rewrite the blockchain with a new key pair and revert any malicious transactions. However, to do this we need to bring the network down for a short period of time while we roll the keys. Once again, this is fine for our small system but clearly not in the real world.

Overall creating our own system has given us a much greater insight into the workings of bitcoin both at the lowest level and on a much larger scale. It’s also indirectly responsible for a fair amount of weight gain around the office. Personally, I am excited to see the direction blockchain work can be taken and what the future holds for it.