No more pet build servers!

Have you ever spent several days setting up a build server? I’ve done this on quite a few projects and I can’t say I’ve ever particularly enjoyed the experience. I think there are a number of reasons for this, chief among them being:

- It takes quite a while to install some of the tooling, e.g. compilers

- If a tool doesn’t function correctly, I’m never quite sure if everything is cleanly removed when I uninstall

- Different tools sometimes clash and special configuration is needed to get them to live together on the same host

- I try to be a good boy and document everything I do, but sometimes I forget, or simply note something down wrong

All of this contributes to something I like to call “pet build server syndrome”. The phrase comes from the idea that a server that has been created and maintained over time without declarative configuration is a “pet”, whereas a server that can be recreated easily is just “cattle”. Check out the Puss in Boots slide in this article.

It’s not a nice feeling to know that your build server is crucial to your project and yet can’t be easily recreated if something goes wrong, or cloned if contributions to your project increase and you need more compute power. What we really need is some way to turn our build servers into cattle. Enter Concourse!

We’ve been using Concourse for several months now and have found it liberating to be able to recreate a build server from scratch in a matter of minutes and store our CI definition along with the code it builds and deploys. We had a few teething problems along the way, both because we were on a learning curve and also because we started using Concourse prior to version 1.0, but overall it has been a great experience. I’d find it hard to go back to non-declarative CI!

What is Concourse?

Concourse is a simple and scalable way to declare your continuous integration as code. It’s compelling because that means that the configuration of your build server is known and repeatable without manual intervention. You can tear down your CI infrastructure and recreate it in a matter of minutes rather than hours or days.

All of this is made possible by the magic of containers. The tooling installed on actual CI host machines should be restricted to Concourse itself. Anything else is wrapped up in images, e.g. compiler, unit test framework, Git. So rather than installing things on the build server, we encapsulate our tools in images and store them somewhere else, e.g. DockerHub.

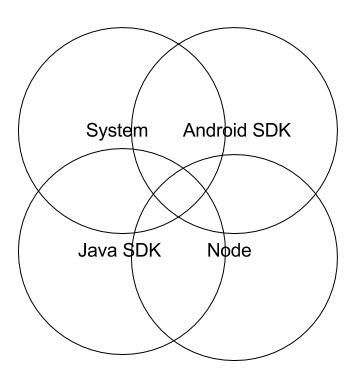

A “traditional” build server might look something like this, with the build system installed onto the same file system as the tooling needed to actually do the builds:

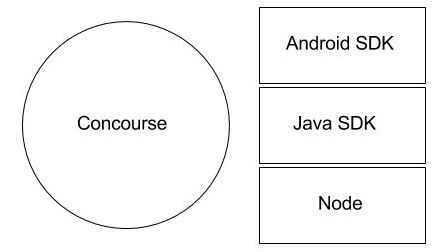

In contrast, a build server running Concourse runs the tooling in containers, which have their own separate file systems.

There’s no overlap and creation of the build server for us involves putting a single binary on a VM, configuring it, running it and then sending build pipelines.

Concourse “pipelines” are YAML files that declare resources to use, e.g. Git repos or Docker images, and contain a set of jobs to execute. In turn, jobs are sub-divided into tasks and each task runs in a container. Some readers may be surprised to learn that Docker and containerisation aren’t synonymous. Concourse uses Garden containers and when a task needs Docker, e.g. to build a Docker image, Docker runs in a Garden container!

The Concourse documentation is very good and there’s an excellent tutorial by Stark & Wayne to get you started here.

Our use case

In this blog post, I want to focus on the very positive experience we’ve had using Concourse for continuous deployment of a microservice-based application written in F# into AWS using Docker Swarm. The application is in a set of repositories under the BristechSRM GitHub organisation, here.

Very briefly, Bristech is a not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to share knowledge within the Bristol tech community, where I work. I help to organise the monthly meetups and we currently use this application to manage our speaker pipeline. I don’t want to go into the details of the application, since it is currently only for use by the Bristech organisers, but I will refer to code in the public repositories.

The important thing to note is that microservice repositories such as sessions or comms have a concourse directory so that their CI pipeline has its home in the same place as the F# code. Resources shared by microservice builds, such as the Dockerfile for the F# compiler tooling are stored in the infrastructure repository.

Our use case makes an interesting case study because we use images that come out of the box with Concourse and our own custom images both for resources and for tasks. In the case of resources, we use Git repositories and DockerHub repositories out of the box and a Docker Swarm resource that we have written ourselves. In the case of tasks, we use the Busybox image for simple file manipulation and a custom image for our F# compiler tooling.

Continuous deployment pipeline

We currently only have a single job for a typical microservice. The definition looks like this:

jobs:

- name: build

public: true

serial: true

plan:

- get: code

trigger: true

- task: build

file: code/concourse/build.yml

- task: create-context

file: code/concourse/create-context.yml

- put: image

params:

build: context

- put: swarm

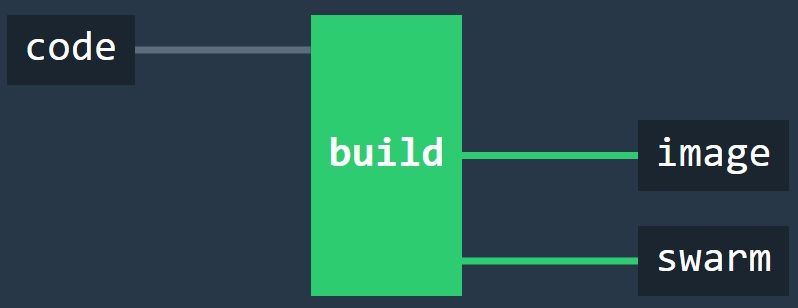

One of the nice things about Concourse is just how readable this is. It says “Get the code whenever there’s a change, build it, wrap it up in a Docker image, push it to DockerHub and then tell Docker Swarm to deploy the new code”. There are more details in the task YAML files and their associated shell scripts, but this pipeline file gives the overall gist.

In the Concourse UI, the pipeline looks like this:

If you want to check out a (much) larger pipeline, then you’ll be pleased to hear that Concourse eats its own dog food. Concourse builds with Concourse and its pipeline is here.

In the following sections, I’ll describe the resources and tasks in the pipeline in the order in which they run.

Getting the code

The plan for our job says

- get: code

trigger: true

In turn the code resource is defined in the pipeline file as:

- name: code

type: git

source:

uri: https://github.com/BristechSRM/comms.git

Git repositories are a standard resource type.

Because we set trigger to true, Concourse polls the Git repository for new commits on master. When it finds some, it pulls the repository. Any subsequent task in the pipeline that requests code as an input then has the directory containing the repository mapped in as a volume in the task container. The code appears as a code directory to shell scripts.

Building the code

Our microservices are written in F#. They use Nuget for package management and FAKE for build.

Our compiler tooling is wrapped up in a custom Docker image, which is created using this Dockerfile:

FROM ubuntu:14.04

RUN apt-key adv --keyserver keyserver.ubuntu.com --recv-keys 3FA7E0328081BFF6A14DA29AA6A19B38D3D831EF && \

echo "deb http://download.mono-project.com/repo/debian wheezy main" | sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/mono-xamarin.list && \

apt-get update && \

apt-get -y install mono-devel fsharp wget

RUN mkdir -p code/.nuget && cd code/.nuget && wget https://dist.nuget.org/win-x86-commandline/latest/nuget.exe && cd .. && \

mono .nuget/nuget.exe install "FAKE" -OutputDirectory packages/ -ExcludeVersion

Here’s what this does:

- We add a key for Mono’s package repository and register the repository in sources for the image

- We then download packages for Mono development, F# and also wget for the next step

- Nuget isn’t in a Debian package, so we get it from a URL

- Then we use Nuget to get FAKE

Putting tooling in images allows us to compile our code and be left with just the binaries. The container itself is destroyed once the binaries have been created. Nothing is installed on the build server.

Here’s the task that does that:

platform: linux

image: docker:///bristechsrm/build-fsharp

inputs:

- name: code

outputs:

- name: binaries

run:

path: code/concourse/build.sh

In brief, it says “spin up a container with F# build tooling, map the code in, run a shell script and map the binaries out”. Once that is done, the tooling can be removed from the machine, leaving a clean build server with nice shiny new binaries!

The shell script looks like this:

#!/bin/sh

set -e

cd code

cp -R /code/.nuget/ .

cp -R /code/packages/ .

mono packages/FAKE/tools/FAKE.exe build.fsx

cd ..

cp code/build/output/* binaries/

The essential thing to note here is that container volumes for code and binaries are created automatically by Concourse. code contains the repository and the script compiles the code and copies the binaries out into a volume that persists when the container is removed.

The binaries are then used as input for the next step, which wraps them up into a Docker image with the Mono runtime.

Creating a docker build context

Creating a Docker image for deployment starts by creating a directory for our docker build context. We take a standard Dockerfile from our code and transfer it to a directory along with the previously built binaries. Running docker build in the next step will wrap up our binaries with the Mono runtime, ready for deployment.

The task looks like this:

platform: linux

image: docker:///busybox

inputs:

- name: code

- name: binaries

outputs:

- name: context

run:

path: code/concourse/create-context.sh

Since we are only copying files with the shell script, we only need limited shell functionality, which is supplied in a small standard image by Busybox.

Building and pushing the deployment image

We are using one of Concourse’s standard images (containing Docker), to build a Docker image containing our code and push it to DockerHub! (Yes, that is mind bending when you first hear about it.)

This is accomplished very simply by the following directive in the pipeline file:

- put: image

params:

build: context

Note that context is an output from the previous task.

In turn, image is defined as a standard Docker image (docker-image) resource:

- name: image

type: docker-image

source:

email: {{docker-hub-email}}

username: bristechsrm

password: {{docker-hub-password}}

repository: bristechsrm/sessions

We need credentials to push an image to a DockerHub repository. How these credentials get onto the build server is described after we look at the final stage in our continuous deployment pipeline - kicking Docker Swarm.

Kicking Docker Swarm

The Git repository that we watch for code changes and the DockerHub repository where we push our microservice image are standard resources supplied by Concourse out of the box. However, there isn’t a resource for a Docker Swarm, so we wrote our own.

A Concourse resource is a Docker image containing three executables:

- check

- out

- in

For something like a Git repository, check looks for new commits on a given branch, in corresponds to git pull and out corresponds to git push. In the case of Docker Swarm, we haven’t implemented check and in, but have written a shell script for out, in order to tell the swarm master to update a particular running microservice. The script looks like this:

#!/bin/sh

exec 3>&1 # make stdout available as fd 3 for the result

exec 1>&2 # redirect all output to stderr for logging

buffer=$(cat)

#Extract variables from json

serviceName=$(echo $buffer | jq -r '.source.serviceName')

nodeName=$(echo $buffer | jq -r '.source.nodeName')

swarmMasterIp=$(echo $buffer | jq -r '.source.swarmMasterIp')

repository=$(echo $buffer | jq -r '.source.repository')

overlay=$(echo $buffer | jq -r '.source.overlay')

accessKeyId=$(echo $buffer | jq -r '.source.accessKeyId')

secretAccessKey=$(echo $buffer | jq -r '.source.secretAccessKey')

export DOCKER_HOST="tcp://${swarmMasterIp}:3376"

docker stop ${serviceName}

docker rm ${serviceName}

docker pull ${repository}

docker run -d -p 8080:8080 --restart=always --name=${serviceName} --net=${overlay} --env=constraint:node==${nodeName} --env AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=${accessKeyId} --env AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=${secretAccessKey} ${repository}

echo '{ "version": { "ref": "'$BUILD_ID'" } }' >&3

There is some boilerplate reassignment of file descriptors at the start, which Concourse currently requires. The rest of the script takes configuration from STDIN and uses it to talk to the swarm master.

This script is built in to an image using this Dockerfile:

FROM concourse/docker-image-resource

COPY ./resource /opt/resource

RUN chmod +x /opt/resource/*

We piggy-back on Concourse’s base resource for Docker images, meaning that Docker and jq (an executable that can parse and filter JSON) are available to our script.

Creating a Concourse rig

We run our Concourse rig in the cloud on AWS, with web server, work scheduler, build workers and build database on separate VMs. There’s a blog in the pipeline (no pun intended!) describing how we set that up, so I won’t go into it here.

If you want to experiment with Concourse, the best way to get started is to bring up a local instance using Vagrant, as described here. You can send pipelines to a local instance in exactly the same way as you would to a full rig in the cloud. If you want to use a microservice pipeline from Bristech SRM, then you will be able to pull the code and build it easily, but of course you won’t be able to push to the DockerHub repo, or contact our swarm master!

In fact, being able to run a local build machine in this way is another very powerful feature of Concourse. If the build breaks and you’re not sure why, you can experiment locally rather than pushing speculative commits to the Git repo and waiting for remote builds to complete. When it builds locally, it will build on a remote rig because everything is in containers.

Sending pipelines

Pipelines are sent to a Concourse instance with the Fly command line tool. Fly can be downloaded from a running Concourse instance. If the instance has no pipelines, you will be presented with a home screen prompting you to do this.

If you want to download Fly from an instance with pipelines already configured, you can use the small icons in the bottom right corner of the home page.

Fly needs to be targeted at a Concourse instance. For an exploratory rig running on a local VM with Vagrant, this might look something like:

fly --target local login --concourse-url http://192.168.100.4:8080

Once a target has been set, pipelines can be sent to it using commands such as

fly --target local set-pipeline --config pipeline.yml --pipeline my-pipeline

In this example, the pipeline.yml file is sent to the build server and will show up in the UI with the name my-pipeline.

Sending secrets

Build servers often need quite a few secrets to do their magic. In our case, we have database passwords, DockerHub credentials and AWS access keys, among other things.

These get onto the build server by executing set-pipeline with a –load-vars-from flag that references a credentials.yml file that we don’t commit to source control.

For instance, here’s the part of our pipeline that declares a DockerHub repo for our comms microservice:

- name: image

type: docker-image

source:

email: {{docker-hub-email}}

username: bristechsrm

password: {{docker-hub-password}}

repository: bristechsrm/comms

The credentials are parameterised. The credentials.yml file would have entries like this:

docker-hub-email: me@example.com

docker-hub-password: Pa33w0rd

Fly replaces the {{}} parameters in the pipeline with values from the credentials.yml file and sends the resulting definition over a secure connection to the Concourse instance. Once the pipeline is on the instance, there is no way to view its YAML definition.

In conclusion

Thanks for reading this far! I’ve tried to get across how Concourse provides a powerful CI solution by allowing your pipelines to be fully declarative and separating concerns into:

- An overall pipeline definition that should be a readable representation of your CI

- Resources used by the pipeline, e.g. Git repos, DockerHub repos, S3 buckets, …

- Custom resources (e.g. a Docker swarm) with executables to check for changes, and push and pull the resource

- Dockerfiles to declare images for tooling

- Individual tasks declaring the image to run, inputs and outputs and …

- … a shell script to execute the task

I’d encourage you to explore Concourse and use it on your projects. There are many more possibilities than those I’ve had space and time to discuss here, e.g. running the tasks in a job in parallel rather than series. There’s a vibrant community at the moment and I was particularly impressed with the help I received on the Slack channel when I was first setting up our rig.