In this post, Richard and Andy will talk you through their ‘Hell Escape’ game project, which is one of the things they’ve worked on during their first few months working at Scott Logic as graduate developers. Although not a games company, Scott Logic welcomes the transferable skills and experience built up from this kind of project such as JavaScript and Scrum.

After six weeks’ induction and intense HTML5 training, which exposed us to a plethora of new technologies and libraries, we finished our first project project building a simplified trading platform. We were ready to move onto something new, and this something new was a game which was one of the worst kept secrets ever!

The idea

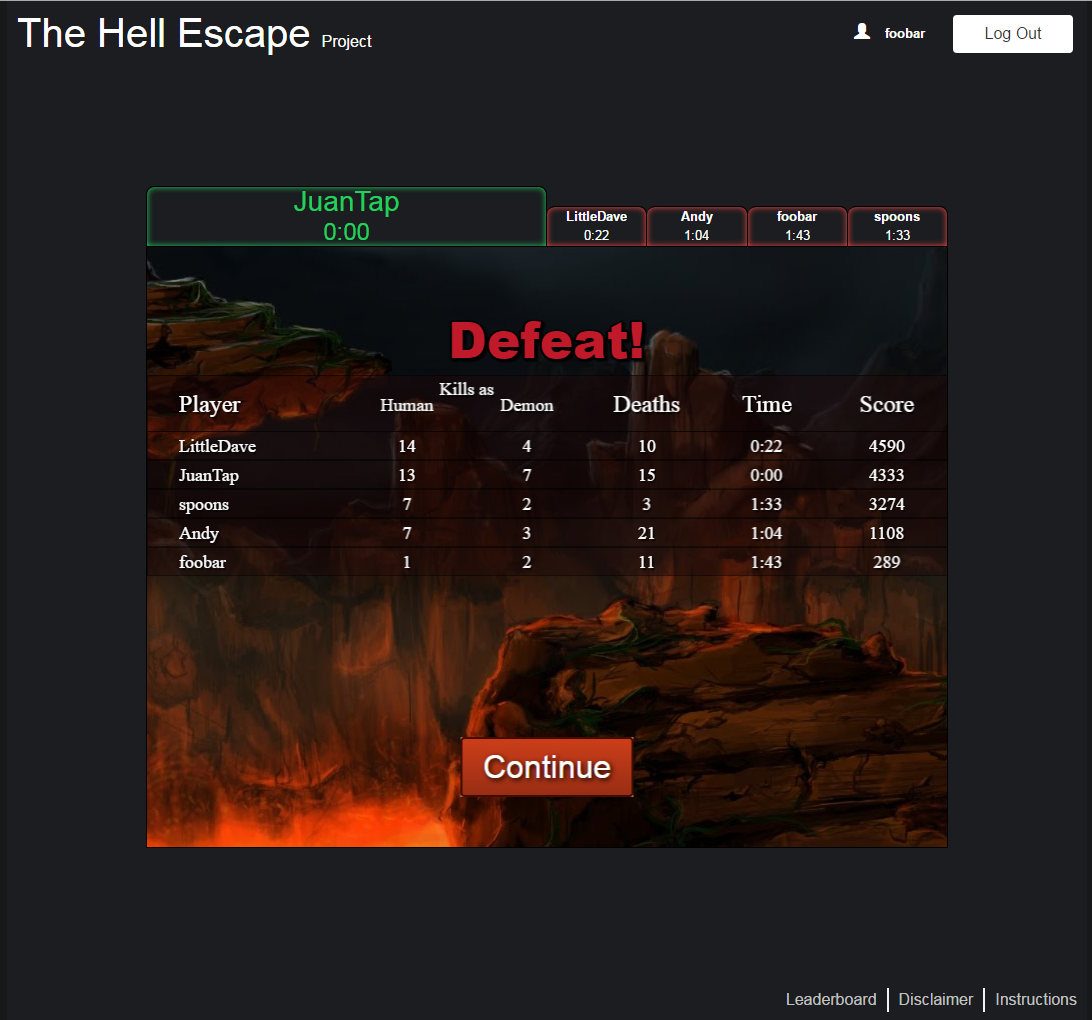

After an initial brainstorming session we narrowed our choice of game down to a ‘Metal Slug’ style platformer with cooperative play, or a player vs player top down shooter, which was described as ‘Pacman where you can also play as the ghosts’. Whilst a cooperative game would have been fun to produce, the lure of player vs player was too strong. Choosing a theme was harder and deciding zombies is an overused genre, we decided on human vs demon.

The tech

We were provided with a list of recommended technologies to use and guidance on how to get everything set up and then we were, to an extent, let loose. Node.js was highly recommended for the server and, as JavaScript was the the main language where our experience overlapped, it was the obvious choice. For any online multi-player game, the communication channel needs to be low latency, with a two-way connection between the client and server. With this in mind we used Socket.IO for the vast majority of the app. We also used Fetch (the next iteration of XMLHttpRequest) when sockets were unnecessary.

The client side of the game was implemented using the JavaScript game engine Phaser, with the rest of the app utilising Knockout.js. Both of these are lightweight packages with Phaser chosen for two reasons: it uses WebGL to help keep the frame rate up, and it had previously been used by others in the office, giving us an easily accessible advice channel should we need it.

Knockout was chosen ahead of other libraries such as Angular and React due to its simplicity and ability to display constantly up to date information through the websocket. We also made use of the Webpack module builder to manage and bundle our Single Page Application (SPA) assets.

Running the project

Using Scrum implementation of Agile development, our weeks were organised into sprints with a main goal achieved by completing stories, tasks and fixing bugs. Although we had doubts this would be useful to a team of just two, it quickly became evident that we were better organised and tasks were being correctly prioritised and estimated, thanks to our daily and weekly meetings. It helped give the project a professional feel and the approach meant we continuously saw tasks we had wanted to tackle, but weren’t essential, fail to make it into the game. Had we been given free reign to do as we pleased with the app, the final product may have been poorer for it.

While we undertook all production ourselves, we weren’t alone. We were supported by other experienced employees acting as our scrum master, technical advisor and product owner. We’d also be regularly stunned by complicated questions, which more often than not, would lead us to re-evaluate and change how we were implementing some functionality.

Lessons learned

The two of us on this project had a very different background which meant we brought distinct knowledge and skills to this project. However, the gap between a university project and a professional project is big and we’ve been amazed by the amount of knowledge we’ve gained through creating this game.

Building the whole app from scratch gave us invaluable experience working with the full technology stack. We found certain areas more challenging, or more enjoyable than others, but it was both necessary and useful not to over specialise or actively avoid working on any particular part of the app. As a two person team, we took part in collective code ownership, we reviewed each other’s code and therefore needed to fully understand and interpret decisions to ensure this wasn’t a perfunctory task. Learning to regularly commit and share our code via Git, as well as effectively review each other's work was key to the game’s development.

Mocking is great

As part of our development process we created unit tests for our code, but found we were unable to test functions that used websocket communication. We then decided to use mocking. By separating the socket communications into a separate layer, we were able to use a mock library to fake the socket and test what was previously untestable. Learning how to mock (and stub and spy) was a headache, but it significantly helped and looking back, was worth it.

Conclusions and improvements

While we are satisfied with the final game, it was nerve wracking to release it to the rest of the company to be played. But the feedback has been really encouraging and everyone seems to be enjoying it.

There are several features we were unable to prioritise but given time we’d like to implement. For example, collectible items (or pick-ups) was trimmed. This would have introduced limited ammunition and health regeneration, adding a tactical element to the game. Making the health pick-ups appear as bacon sandwiches, cake and coffee would also resonate with many in the office.

Similarly, it seems five or six-player games were a lot of fun but games limited to two or three players could be less interesting. This could’ve been improved with the addition of computer controlled opponents, but implementing artificial intelligence would be a complicated task. The demons also had a slightly slower movement speed than humans which, in a two-player game ended up causing a ‘Benny Hill’ like situation. This was quickly and easily remedied by fine tuning the game’s config file, allowing a single demon to catch and kill a human.

Overall, it’s been fun, interesting and challenging making our game. We’re very pleased with the results and the amount of knowledge we’ve gained in the process.