The Performance tab of Chromium (Google Chrome) DevTools is a powerful tool for analysing application performance. It can however be found lacking when looking at some aspects of complex multi-window Electron web-desktop applications. In this post, I’ll introduce the related but lesser-known Tracing tool, and show how it can be used with Electron.

The need for a tool that goes further

DevTools’ Performance tab (formerly Timeline) is built to analyse what goes on within a single web page. Electron is much more than that, which brings in a few additional aspects to analysing performance.

An application has multiple processes: the main Node.js process, and one for each of the multiple windows. They all interact and can affect each other’s performance, so looking at a single one in isolation isn’t always sufficient. It would be practically impossible to have a comprehensible view of what’s going on by looking at multiple DevTools instances (one for each process) - they’re all disconnected, and there isn’t a common time axis.

While normal web applications may open and manipulate a few popup windows, Electron applications can be much more active in managing their browser windows (renderers). This type of activity can be analysed to an extent using a debugger attached to the main process, but that only goes as far as the JavaScript engine - it’s not possible to drill down further to see what exactly is happening.

Finally, the capabilities Electron provides allows us to build applications that far surpass the performance demands of a normal web application. An application could, for example, have many full-screen windows on a multi-monitor array - with the corresponding amount of workload to drive them, and/or could be using many short-lived dialog windows as part of the application experience. Contrast with a normal web application’s usual single window, with the invisible renderers (minimised windows or non-focused tabs) backgrounded by the browser and deliberately starved of resources. We can put more demand on the underlying Chromium than a standalone Chromium instance would likely ever need to handle - increasing the likelihood that we’ll encounter situations that require digging deeper to analyse and maintain/improve performance.

Multi-process architecture

You may be aware that each Chromium tab runs in its own process, in order to isolate them from each other for security and containment of crashes. This is how all your other open tabs are unaffected when one crashes and shows the “Aw, Snap!” message. We can see these processes in the operating system’s task manager, where we’ll also see that there are quite a few more processes than we have tabs open. Toggling on the command line column reveals that all but one of them were launched with a --type argument.

This is Chromium’s multi-process architecture, in which each type of process has a particular role. The most important types are:

- Browser - the main process, that performs central functions and coordinates/controls all the other processes.

- Renderer - renders a particular page; we’ll have one per open tab, or any iframe from a different origin to its host page. There’s also one for every browser extension that’s running.

- GPU process - an intermediary between the other processes and the actual GPU (Graphics Processing Unit). It exists primarily for security reasons.

The architecture is carried over to Electron, where the browser process also runs Node.js, and is called the main process. In addition to it’s Chromium-derived responsibilities, it runs the application’s main script.

Profiling individual Electron processes

Mainstream profiling tools remain the most suitable options for profiling or debugging your code within the main process or a particular renderer process.

For the main process, launch Electron with --inspect (as you would with standalone Node.js), and attach an external debugger (such as your IDE, or DevTools (!)) to it.

For a renderer process, call webContents.openDevTools() on its BrowserWindow. You may find it convenient to define a keyboard shortcut within your application that does this. These are called accelerators in Electron, and an API is available to register them.

I have however found some aspects of DevTools’ Performance tab to be more flaky within Electron than in standalone Chromium/Chrome. Most notably, I often find that the frame information is missing from the timeline and the FPS (frames per second) graph at the top.

Tracing in Chromium

The tracing tool allows us to look deep into the internals of Chromium. Some of the information available is useful for web application developers, but much of it is only meaningful and useful for developers of Chromium itself. To complement the DevTools’ Performance tab for example, you could use it to investigate why things like Update Layer Tree are taking a long time, or what’s going on in the mysterious grey System part of the task-type donut chart alongside Scripting/Rendering/Painting.

I’ll take you through the core things you need to know; you may find it helpful to open chrome://tracing for reference.

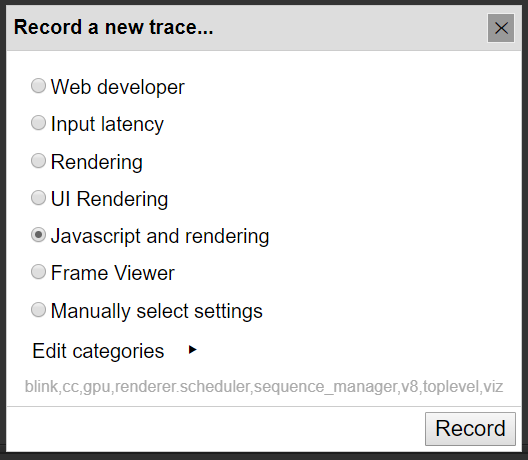

The first step is to record a tracing run. The Record button brings up a dialog where we need to choose which information will be captured. Several preset options are offered, and the Manually select settings option allows a custom selection to be made from well over a hundred individual categories. Enabling too many at once, particularly ones from the Disabled by Default section, can take a heavy toll on performance and generate a huge amount of profiling data that the viewer may not be able to display later. Once tracing is started, the dialog shows data buffer usage, and provides a button to stop tracing - just like with DevTools’ Performance tab (but without a timer, unfortunately).

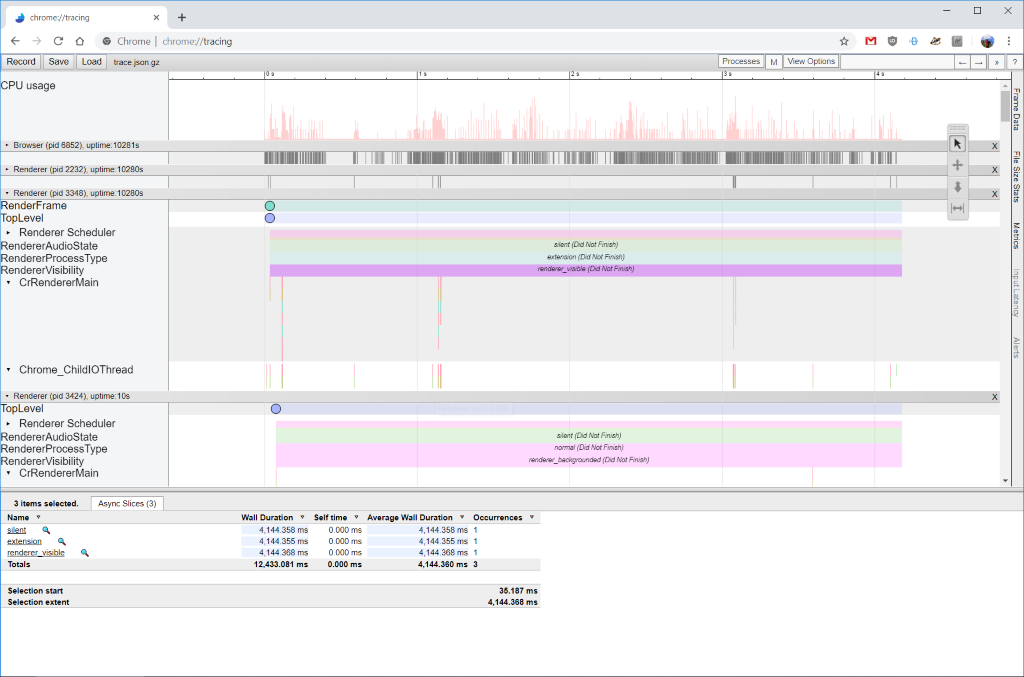

The recorded trace is then loaded, which may take some time. The main view area is a timeline divided into swimlanes; one for CPU usage, and one for each process (see screenshot at start of this section). A single time axis runs across the top. Each swimlane is labelled with its process type, process id, and window/document title (if applicable). Within each process, a number of event timelines are shown for its threads and other activity. This includes a type-based main thread, such as CrBrowserMain, CrRendererMain, or CrGpuMain. What exactly is included (in terms of threads as well as the events within those threads) depends on the categories selected before capturing the trace. Clicking individual events reveals further timing detail, and any other information associated with the event.

Navigation is via the mouse (using various tools from the floating toolbar), and much-needed keyboard shortcuts - which are explained in the “?” help menu at the top right. There is also a search facility. The “M” button at the top displays the trace metadata, which includes system information and the configuration/categories used for the tracing run, all in JSON format - more on this later.

Processes that aren’t of interest (e.g. other tabs, extensions) can be collapsed or hidden. For hygienic profiling isolated from side-effects however, I recommend instead to use a dedicated clean standalone installation of Chromium. You can download a stable build by following these instructions.

Content tracing in Electron

Tracing is also available in Electron, where it’s called content tracing. The word content comes from content module, which is the part of Chromium that’s included in Electron. The module contains all the core web platform features, without the complementary bits that make up the browser chrome such as sync, autofill, and omnibox (address/search bar).

The content module doesn’t include the tracing viewer we saw earlier, so tracing in Electron involves first capturing a trace to a file, and then opening it using a Chromium browser.

Capturing a trace

In the absence of the tracing UI, there are two ways to start and stop a trace in Electron.

The first uses command line flags, a method that’s also available in Chromium. It’s useful for tracing the startup of your application, or as a convenient way of tracing some short activity that you can carry out immediately after startup - before the volume of captured trace data becomes too big for the viewer to handle. Various flags are available for control and configuration, but the simplest way I’ve found is:

- Define the configuration in a JSON file, equivalently to what we would do from the dialog in Chromium (more on that later) - plus a duration in seconds after which to stop tracing, and an output filename for the captured data.

electron.exe --trace-config-file=./trace-config.json- Carry out the activity you want to profile.

- Wait for the duration to elapse, at which point the captured trace data will be written to the file defined in the configuration.

The wait in the final step is important; closing the application sooner would not give the main process the chance to gather all the tracing data from the other processes (renderer, GPU) - and we’d end up with an empty or incomplete trace.

The second method is driven from your application’s main script, and uses the contentTracing export of the electron module. Tracing is started using the startRecording() method which accepts configuration as an argument, and is stopped using the stopRecording() method. The captured trace data is written to disk as before. This method allows more targeted control over when tracing starts/stops, but does require code modification. It would be quite easy to improve on that by defining some keyboard shortcuts within your application, as you may already have done e.g. for launching DevTools.

Configuring tracing

As we’ve seen, in the absence of the tracing UI, the tracing configuration needs to be specified through a configuration file/object (it can also be passed in using command line flags). This section will take a look at how to assemble such a configuration.

The following JSON configuration file is equivalent to the JavaScript and rendering preset from the chrome://tracing dialog. The included categories are taken from the dialog UI, the tracing will run for 30 seconds, and will write the captured data to the file we specify.

{

"startup_duration": 30,

"result_file": "./trace.json",

"trace_config": {

"included_categories": ["blink,cc,gpu,renderer.scheduler,sequence_manager,v8,toplevel,viz"],

"excluded_categories": ["*"]

}

}

If the file isn’t valid JSON, there won’t be any error/logging to inform you of the problem, and the tracing will not start.

The configuration used for capturing a trace is included at the end of the output file as part of the trace metadata. It can be viewed directly, or via the previously-mentioned “M” button in the trace viewer. This is useful for repeating the trace later after you might have modified the configuration file for other purposes.

Categories for tracing

To find other categories that may be of interest, you can look at the other presets or under Manually select settings in the tracing dialog. I’m not aware of any documentation of what’s included in each category, so your best bet is to familiarise yourself with some Chromium terms and general programming acronyms, and try things out. Terms appearing as/within category names include blink (the browser engine; the WebKit fork), browser (main/browser process), cc (Chromium compositor), devtools, gpu, input, ipc (inter-process communication), skia (graphics engine), v8 (JavaScript engine), and viz (visuals).

For the most part, the categories of interest you see in the Chromium tracing dialog will be available in Electron. Should you wish to check exactly which ones are available, use the getCategories() method of contentTracing.

It’s a subset of these categories that Chromium DevTools’ Performance tab captures. Those are all categories that are likely to also be useful in tracing. We can find out which ones they are by inspecting DevTools using another DevTools (Ctrl+Shift+I), finding timeline_module.js (the Performance tab needs to have been loaded), pretty-printing it (button on the lower left), and the finding the startRecording() function. Place a breakpoint after the categoriesArray is composed, then start profiling from the original DevTools. The value of the array shows the following categories in use:

devtools.timeline

disabled-by-default-devtools.timeline

disabled-by-default-devtools.timeline.frame

v8.execute

blink.console

blink.user_timing

latencyInfo

disabled-by-default-v8.cpu_profiler

disabled-by-default-v8.cpu_profiler.hires

disabled-by-default-devtools.timeline.stack

Looking at the code within startRecording(), we see other categories which would be included if we enable options such as screenshots or advanced paint instrumentation (including layers):

disabled-by-default-devtools.timeline.layers

disabled-by-default-devtools.timeline.picture

disabled-by-default-blink.graphics_context_annotations

disabled-by-default-devtools.screenshot

We also see categories relating to DevTools experiments (including hidden ones) such as devtools.timeline.invalidationTracking, which can be enabled by following these instructions.

Tracing tips

Which renderer process corresponds to which window? The tracing viewer shows process type, process id, and window/document title (if applicable). For multi-window scenarios where titles may not be unique, I recommend adding a development-mode flag to add some unique prefix for disambiguation.

Where on the timeline is the bit I’m interested in? It can be difficult to know where too look, time-wise. One technique is to leave a few seconds of idle-time before carrying out the activity of interest, to make it easier to spot. That doesn’t always work so well. A technique I’ve found useful is to start the tracing on-the-minute (or half minute), and later note the time when you carry out the activity of interest. For example, start tracing at 9:00:00, perform action at 9:00:10, then look at the timeline at the 10-second mark. You may find it useful to temporarily enable seconds in your operating system’s clock.

What’s this trace8.json file, again? It’s easy to forget what you traced and why. Perhaps you did before-and-after tracings to evaluate an attempt at optimisation. I recommend keeping your trace files organised using folders and meaningful filenames.

Memory tracing

The tracing tool also includes MemoryInfra, a timeline-based memory profiling system. This too can be captured in Electron, giving a deep and unified view of memory usage across all the processes. Usage is explained on the linked page and others linked from it, and is beyond the scope of this blog post.

Capturing is enabled via the namesake category, and configured via an additional section.

{

"trace_config": {

"included_categories": ["disabled-by-default-memory-infra"],

"memory_dump_config": {

"triggers": [

{ "mode": "light", "periodic_interval_ms": 50 },

{ "mode": "detailed", "periodic_interval_ms": 1000 }

]

}

}

}

MemoryInfra is just one of the many facilities within the tracing tool - many other categories also have non-standard data within their events, and tools to analyse that data.

Conclusion

The Performance tab in DevTools serves most of our profiling needs. The tracing tool provides a deeper view into what’s going inside Chromium, and for multi-window Electron applications has the added benefit of showing all processes on a common time axis. It’s certainly an advanced tool and not one you’d expect to use often (although developers of Chromium itself might), but it’s worth being aware of it for those problems where nothing else will do.

References and further reading

In addition to the inline links above.

- The Trace Event Profiling Tool

- Recording Tracing Runs

- Understanding about:tracing results - a long read, but it will save you time.