In highly-visual, rapidly-updating, multi-window, buzzword-laden apps performance is a big concern. With WebWorkers, SharedWorkers and ServiceWorkers we have a number of options for moving complex scripting tasks off the critical path. However, rendering can be more of a dark art. In this post I’ll dig into how one browser (Chromium) uses renderer processes and how you can use this knowledge to your advantage.

The Chromium Process Model

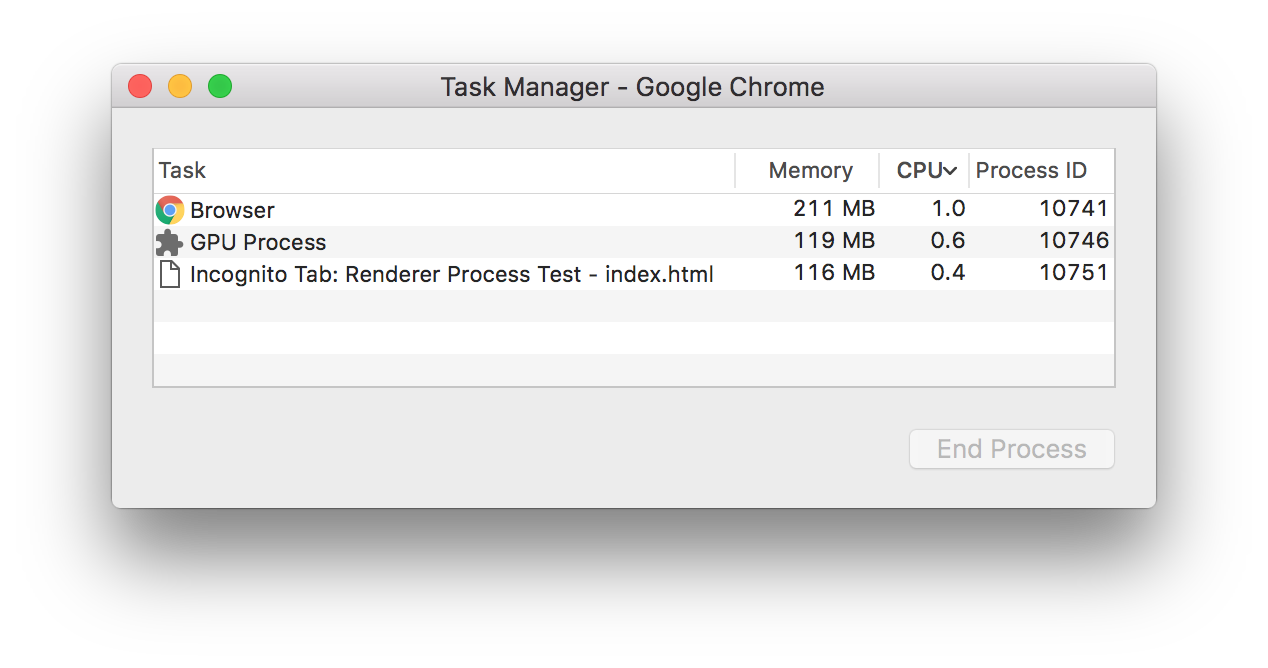

Starting with a clean (incognito) instance of Chrome and disabling extensions (open -a "Google Chrome" --args --incognito --disable-extensions "http://localhost/"), it’s time to crack open the task manager (Window -> Task Manager) and see what’s running -

A bit of digging in the documentation reveals that -

Browser- singleton task which manages renderer process interactions with the host OS (e.g. window management).GPU Process- singleton task which manages renderer process interactions with the (you guessed it!) GPU.Incognito Tab: Renderer Process Test - index.html- a renderer process task for the tab. In this case there’s only one but there’s normally one per tab/extension.

You might also have noticed that, in this example, each task is running in its own process (they each have a different Process ID). The main motivation for this multi-process model is security, a classic defense-in-depth strategy. If an exploit ever does manage to hijack a renderer process, it still has to work it’s way through another layer before it can attack the OS/GPU and cause significant damage.

Another more interesting benefit from the perspective of this blog post though, is the potential for maximising renderer performance by spreading the renderer processes across the available hardware. However, to do this we’ll need to understand how renderer processes are allocated and the degree to which we can influence that.

A Quick Demo

We know that Chromium tries to allocate one renderer process per tab from the documentation but what does that translate to in real-life. In the following video, when the renderer process task appears for the new tab, keep an eye on whether it is allocated a unique process ID -

In the first example, the user manually opens a new tab which results in a separate renderer process being created. Excellent! A new renderer process is exactly what we were looking for. However, we can’t expect users to open links in new windows, let’s do it programmatically instead…

In the second, we try to programmatically mirror this behaviour using a target="_blank" link which results in the existing renderer process being shared. Dagnamit! If we can’t programmatically open a window in a separate renderer process then this idea’s dead in the water…

In the final example, we additionally add in a rel="noopener" attribute on the link and the new tab gets its very own renderer process again. Excellent (again)!

So what exactly’s going on here? Time for a bit more digging through the docs.

Renderer Process Allocation

The process model design document describes how renderer processes are allocated to tabs. Whilst it can actually be controlled using command-line flags, the default behaviour process-per-site-instance is described as -

Chromium creates a renderer process for each instance of a site the user visits. This ensures that pages from different sites are rendered independently, and that separate visits to the same site are also isolated from each other. Thus, failures (e.g. renderer crashes) or heavy resource usage in one instance of a site will not affect the rest of the browser. A “site instance” is a collection of connected pages from the same site. We consider two pages as connected if they can obtain references to each other in script code (e.g., if one page opened the other in a new window using Javascript).

This seems to describe the difference in behaviour we witnessed between the first two examples, i.e. programmatically creating the new window causes the pages to be considered connected and therefore allocated to the same renderer process. However, it doesn’t explain why rel="noopener" worked.

A bit more digging unearthed the site isolation design document which describes the implementation progress of the following as Complete -

Some window and frame level interactions are allowed between pages from different sites. Common examples are postMessage, close, focus, blur, and assignments to window.location, notably excluding any access to page content. These interactions can generally be made asynchronous and can be implemented by passing messages to the appropriate renderer process.

The interesting bit here is the specific exclusion of interactions that access the newly opened tab’s content. By specifying the link as type noopener we’ve effectively isolated the two tabs from each other in the same way as content from different sites would be isolated. And that’s what has allowed Chromium to split the tabs into distinct renderer processes.

Limits on Renderer Processes

Moving everything into it’s own renderer process is great in theory but it’s important to remember that at some point we might still run into the fundamental constraints of the hardware the browser is running on and the singleton browser/GPU processes. As well as these, it’s also worth knowing that there’s a maximum number of renderer processes enforced by Chromium across the entire browser instance (across all profiles & extensions).

The bad news is that if the browser hits this limit then it will start recycling renderer processes. Our tricks from above no longer apply as this demo shows -

As you can see, in all 3 cases the renderer process is shared by the new tab. However, there is some good news! The algorithm Chromium uses for calculating the maximum number of processes assumes a user wants to allocate half of their system’s physical memory to these processes and that each process (on a 64-bit system) will take up approximately 60MB. Therefore on modest desktop hardware featuring 16GB of RAM, Chromium will permit up to 136 renderer processes. So even if we assume a particularly heavy user with 80 open tabs and 10 extensions running, our multi-window app could happily open 10 with plenty of room to spare.

Another reason to use noopener

Obviously splitting your app into multiple renderer processes isn’t a performance magic bullet. There’s a memory and CPU overhead to each process and using multiple windows unnecessarily is going to be confusing for users. However, in cases where you are already using multiple windows, it’s worth understanding a little of what’s going on behind the scenes.

Hopefully this has served as a useful introduction to renderer processes. I’d previously heard about the security problems that can occur when not using noopener but I’d certainly never considered it’s potential to improve performance.