From server to mobile, we’ve seen web technologies being used to create applications well beyond the traditional website. While tools such as Electron exist to also enable desktop app development, I was recently asked by a colleague to investigate how feasible it was to create a multi-window desktop-like app directly in the browser.

Introducing the demo application

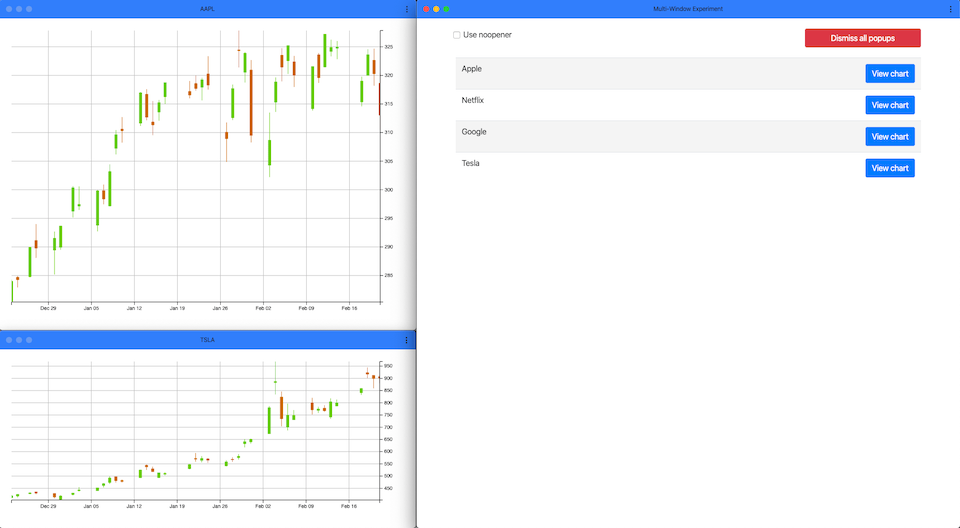

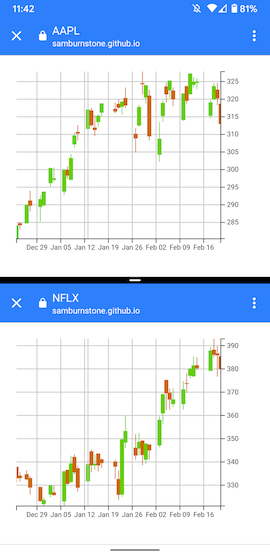

As part of this research, I created a demo application that displays a list of stock prices. Each item in the list has a button that opens up a chart showing the last 3 months of stock prices for that given stock.

The window layout is persisted to local storage upon leaving the app and restored when re-opened. If the tab containing the stock price list is closed, then the pop-ups will also be dismissed.

In order to demonstrate cross-window communication, an annotation is added to all the charts when a user interacts with a pop-up.

The rest of this blog post will build up to creating an app like the one shown above (you can see it in action here). We’ll start by discussing the very basics of how to open a window and end our journey by making the app feel more “desktop-like”. It’s an exciting area of development so please read on to find out more…

Opening a new window

Opening a window is pretty simple:

window.open(

"https://www.example.com",

"popup-1",

"resizable"

);

This opens a new “pop-up” window with the same dimensions and position as the main browser window. I’d encourage you to check out the MDN docs if you’re interested in understanding the function’s parameters in detail, however a quick summary of what we’re doing here:

"https://www.example.com": This is the url we want to open in our pop-up window"popup-1": The window’s name. If this is unique, the browser will open a brand new window. However, if"popup-1"had already been used as a name for a pre-existing window, the url will be loaded into that window."resizable": One of the many “window features”. We’ll go into this in a little more detail later on. Usingresizablewill force the browser to open the url in a pop-up window rather than simply opening the window in a new tab.

Let’s say we don’t want the new window to obscure the main application and instead be able to specify its height and width, as well as its position on the screen. We can use the aforementioned windowFeatures parameter to provide these values. The following code will open a new pop-up positioned near the top left corner of the screen with an outer width and outer height of 400px.

window.open(

"https://www.example.com",

"popup-1",

"top=100,left=100,width=400,height=400"

);

A quick word on pop-up blockers

When creating a new window, you’ll probably find your browser presents you with a warning looking something like the image below.

Modern browsers all come with built-in pop-up blockers designed to prevent nefarious sites from flinging new windows at you. Most browsers only block pop-ups that are created programatically; a new window created in response to a user clicking on a link will not be blocked. On the other hand, a programatically created window will result in the browser asking the user whether they want to whitelist the site.

Performance implications of many windows

Chris Price discussed the effect of using noopener when new windows were created when clicking on a link. While I suggest you give that post a read-through, the core point to take away from it is that any child windows retain a reference to their parent window via a window.opener property and will run in the same “renderer process”. The reason for this was highlighted by Jake Archibald: to enable cross-window access to the DOM.

For most apps this shouldn’t be a problem, however if our pop-ups were to contain intensive applications, users may begin to have a degraded experience due to the apps all running within the same renderer.

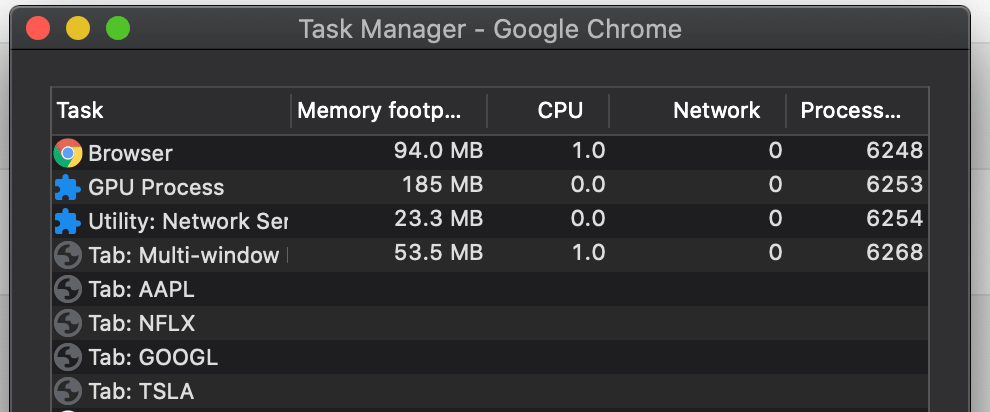

We can see this is the case in Chrome by opening the browser’s Task Manager. If you take a look at the screenshot below, you can see our pop-ups are grouped under the “Multi-window” container tab - this contains the script that spawned our child windows.

Forcing the browser to create a separate renderer process can be done by supplying noopener as part of our window features string. This works in Chrome, Firefox and Edge.

window.open(

"https://www.example.com",

"popup-1",

"noopener,top=100,left=100,width=400,height=400"

);

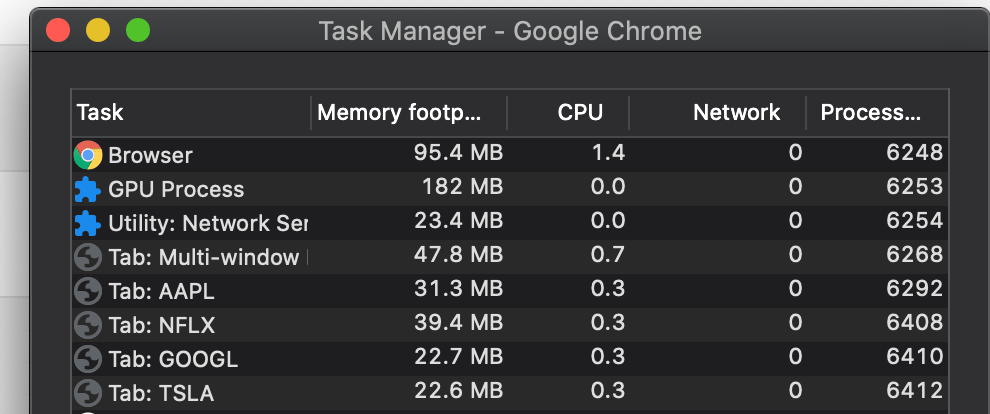

Now if we take another look at the Task Manager, we can see that each window now has its own process (note the identifiers in the right-most column).

Just a quick note on something that tripped me up: I initially assumed that I could provide noopener=true, however this isn’t valid according to the spec. Examples of accepted parameters to enable the noopener feature are noopener and noopener=1.

Chrome

This is all looking pretty promising. However, if we go ahead and run the above in Chrome, then we’ll run into an issue.

Chrome seems to disregard the specified dimensions (we were a expecting a 400x400 pop-up window). I had a trawl through the Chromium bug-tracker and found this open issue.

A slightly nasty workaround I found for this was to supply the layout via query params and then get the pop-up to resize itself using the window.moveTo and window.resizeTo functions.

// In the main application

window.open(

"./popup.html?layout=100,100,400,400", // Window position and dimensions supplied via query params

"popup-1",

"noopener"

);

// In the pop-up

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", () => {

const { layout } = queryString.parse(window.location.search); // Use "queryString" library to parse params

// Layout is sent in format "x,y,width,height"

const [x, y, width, height] = layout.split(",");

// Now resize the pop-up

window.resizeTo(width, height);

// Set the popup's position

window.moveTo(x, y);

});

This works to some extent, however we can see there’s a rather nasty flash where the pop-up is created at the same size as the main browser window, before being resized and repositioned. This problem exists on both Windows amd macOS, but its most pronounced in the latter due to the platform’s love of animating window size changes.

A word of warning: window.resizeTo requires the width and height be in terms of the window’s outer height and width, whereas the window features expect the inner height and width.

Firefox

Firefox also supports noopener as a window feature which results in the browser creating separate threads for each of our windows. It’s worth noting that it seems to have a number of quirks when positioning windows, particularly when multiple monitors are involved.

Even with pop-ups enabled, Firefox seems to prevent sites from programatically opening more than 20 pop-up windows. It looks like this is an additional protection for users where the browser will allow sites to open 20 windows and anything above is deemed to be an “abuse” of the user’s permission. Subsequent pop-ups beyond the limit will result in Firefox blocking them and presenting a banner to the user requesting further permission for the site to open the remaining windows. From my testing, this banner is only presented once if the user allows the pop-up count to exceed the limit.

Edge

Microsoft recently released a new version of Edge which is now built on top of Chromium. While there are many implications of this switch, a big upside is that Edge behaves in the exact same way as Chrome when it comes to laying out windows.

Closing pop-ups

If a user has multiple windows spawned from the main application, it’s unlikely they’ll want to have to dismiss each window separately. It’d be much nicer if we could close all our pop-ups when closing the main window. This is quite simple when we have a reference to the popup window:

const popup = window.open(

"https://www.example.com",

"popup-1",

"height=200,width=200"

);

popup.close();

However, things get quite a bit trickier when noopener comes into play.

const popupWithNoopener = window.open(

"https://www.example.com",

"popup-1",

"height=200,width=200,noopener"

);

popupWithNoopener.close();

// TypeError: popupWithNoopener is null

Uh oh! When we use noopener in order to force the browser to create a separate process for our new window, we’re no longer able to get a reference to it via window.open.

While other windows cannot directly close another window created with the noopener param, if we can somehow inform the pop-up window it should close itself, then that should work.

To communicate across separate windows I used this library which provides a cross-browser implementation of BroadcastChannel. This means we can send a “DISMISS_ALL” message to the pop-up windows when the main app is closed.

Here’s Chrome closing all windows related to our application when the “main window” is closed:

Unfortunately, when trying this in Firefox, the browser presents us with the following console warning:

Scripts may not close windows that were not opened by script.

This leaves us in a bit of a pickle! We’ve created our window running in a separate process, however we have no way of closing this window - not even from the pop-up as it wasn’t responsible for opening itself. This issue has already been raised on the Firefox issue tracker.

Multi-monitor support

Many users nowadays hook their machines up to multiple monitors. I was intrigued to find out how well modern browsers would support laying out windows across multiple monitors, particularly when restoring a saved layout.

Firefox doesn’t play ball here, with windows sometimes opening on the wrong screen after restoring the layout. I struggled to narrow down exactly why this was happening, but it’s possible the width of the main browser window and the proximity of it to any pop-ups was the cause.

As for Chrome, in order to get around the issue with positioning windows with the noopener parameter we used the window.moveTo function. This worked fine when only a single screen was involved, however this function is unable to move windows between screens.

Chromium have an initiative dubbed Project Fugu that’s looking to fix this as well as a bunch of other issues. The project’s stated goal is to “to close the capabilities gap with native to enable developers to build new experiences on the web while preserving everything that is great about the web”.

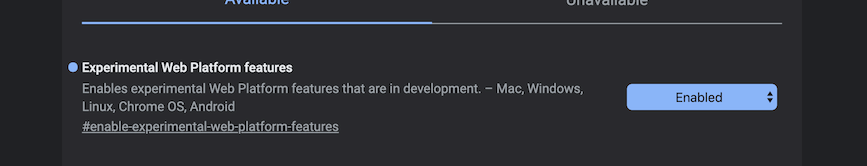

Project Fugu is still very much in progress, however some features are already available and are hidden behind feature flags. These flags can be found by typing about:flags into the address bar. This spreadsheet is a great resource if you’d like find out about all the features that make up Project Fugu and their current implementation status.

The one we’re looking to enable is “Experimental Web Platform features” and the specific issue that relates to window placement can be seen here. There’s also an in-depth explainer that outlines use-cases and the future work planned.

After enabling the flag, Chrome is able to move our pop-up windows across monitors (note that you’ll need to be using a Chromium browser >= version 80 for the new window placement functionality to work).

Other browsers based on Chromium can also enable these experimental features (typing about:flags into Edge results in a similar list).

A little less chrome in Chrome

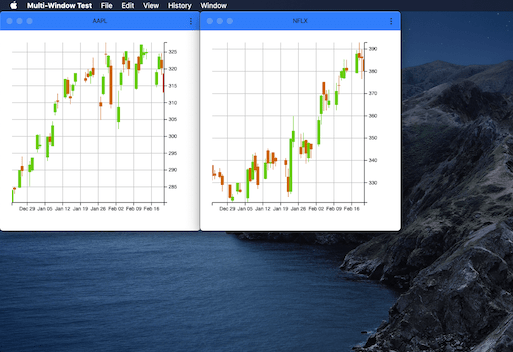

Taking a look at our pop-up windows, we can see both Firefox and Chrome add an address bar. We’re able to remove these by converting our application to a Progressive Web App (often shortened to PWA).

Before writing this blog post, I thought PWAs were specifically for mobile platforms, however it turns out this isn’t the case and that some Desktop support exists. It’s worth being aware that it’s just Chromium-based browsers that support them for now, however Firefox are looking into it.

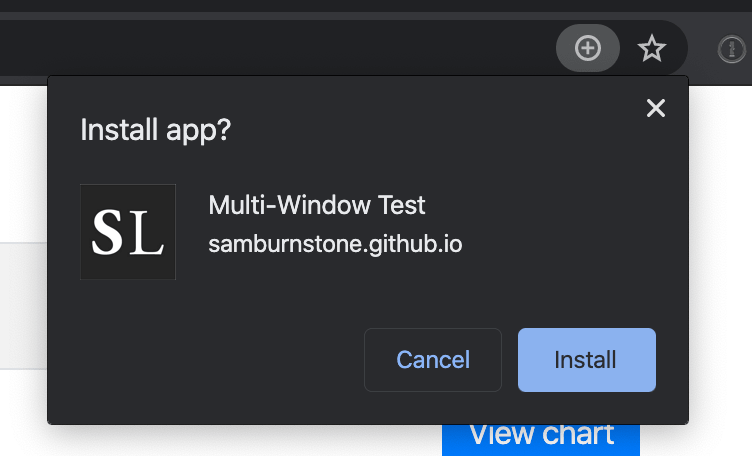

In my example, I used the Workbox Webpack plugin maintained by the Chrome team and quickly added a web app manifest. Without going into too much detail, the important thing to note is we set the “display” key to “standalone”, which will result in our PWA opening without any browser UI. As long as your web app passes the criteria for being “installable”, when you next open the page in Chrome, you should see a small “+” button appear in the address bar (see screenshot below).

Clicking “install” will result in the application being added as a Chrome app (you can view them by typing chrome://apps in the address bar). You can now launch the application as if it were a native app, for example, using the start menu on Windows or using Spotlight on macOS.

The age old battle: Windows vs Mac

Web developers are accustomed to dealing with browser differences, however multi-window applications bring an additional complexity: worrying about cross-platform behaviour.

Taking Chrome as an example, after enabling the experimental feature flag mentioned earlier, windows can be freely moved across monitors on both platforms. I wanted to see how they’d display the exact same layout.

The layout in question contained two 400 x 400 pop-up windows, positioned alongside each other in the top-left of the screen.

On Windows we can see that there’s a slight gap of 10px to the left of the first window. If we wanted to move the window to the very edge we’d need to supply an x position of -10.

On macOS, the layout looks pretty similar, however due to the menu bar located at the top of the screen, each window’s y position is actually 23. Note that the left-most window is flush against the left-side of the screen, unlike on Windows.

Overall, I was pleasantly surprised by how similar the layout was displayed across the two platforms. We can see there are slight differences that would need to be taken into account if we wanted to cater for users that weren’t tied to a particular platform.

Mobile

Out of interest, I thought I’d take a look at the PWA running on mobile. I must admit, I wasn’t expecting much, however I was pleasantly surprised to see the cross-window communication working between split windows.

This goes to show the potential of PWAs: with relatively minimal effort, we have an application that’s capable of running in the browser, on the desktop and also on mobile.

To window.close thing’s off

We’ve seen how to open, position and close pop-up windows. We also covered creating these windows in a separate process in order to prevent us from blocking other windows. Finally, to add a bit of finesse to our application, we saw how we could create a Desktop PWA to remove those unsightly address bars from our windows.

There’s definitely a lot of work still to be done, but it’s evident the Chromium team are working hard to try and level the playing field between the web and native apps, with other browser vendors starting to get on board.

Feel free to have a play around with the project created as part of this investigation. The source code is available on Github.