We’re told that we need to commit early and often. But what does this mean…? What is the right frequency? When should branches be used? When do they work well, and when should they be avoided?

If my last post was about the why, this one is about the when. We tend to figure these things out on our own, we try things in all sorts of different ways until we land roughly on an approach that normally resembles what the rest of us (hopefully) do.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”

George Santayana

The thing is we all go through this dance on our own. There is a ton of information out there about how to do things even why, but what about when? What I’m hoping is that in sharing some of my experience you can understand the benefits of the approach many of my colleagues and I take to good effect.

When to commit

As we go through our careers we typically learn over time to increase how often we commit our changes. This continues until we have normalised with the other developers we work with. But why do we all have to figure this out by trial and error. What are the benefits, why do we all repeat the same process of experimentation? What could we start doing right from the outset?

The ultimate goals are to have commits that:

- make sense

- build and do not present and (additional) test failures

- present value to the codebase

Don’t be afraid of making too many commits. With tools like git they can be tidied up after the event. Even if this isn’t possible, it’s still far less disruptive to have too many commits than too few.

One of the best ways to demonstrate the best practice is to demonstrate the down sides of each approach.

If you commit too rarely, the code history will:

- harder to review (all changes will be bundled together)

- prevent selection of discrete changes

- leave a poorer source control history

- delay others from benefiting from where you are earlier (see branching below)

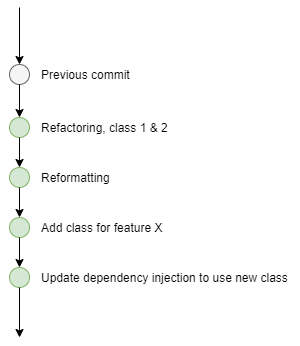

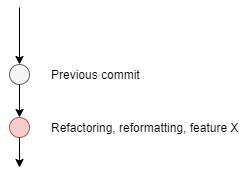

It can be all too easy to refactor and add functionality in one commit. But each of those actions could be saved in individual commits. Your functional changes wouldn’t also include the noise of your refactoring, and vice versa.

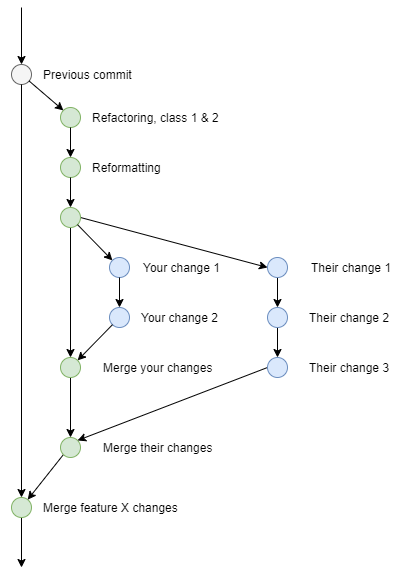

What if you wanted to keep the refactoring and reformatting, but not feature X?

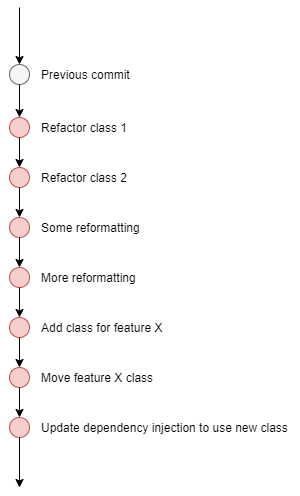

If you commit too often, the code history will:

- potentially not make sense, making for a confusing history

- present issues if the feature needs to be reverted (which of the sea of commits need to be reverted?)

What if you wanted to revert feature X, which commit/s do you need to revert?

Software development is an iterative process, no one gets everything perfect first time. Committing iteratively demonstrates your ability to attack the task at hand in a measured fashion. No one should ever hold you to account for the quantity of your commits, unless you go over the top. Again, remember the rules: each commit should enhance the codebase and not present any new problems. That is, it should build and the tests pass (at least to the degree they did before).

This blog is maintained within a git repository - here’s my commit history for this blog post!

Now imagine a scenario where two (or more) of you are working on a feature. You may both want or need some refactoring changes. If you make these in a discrete commit, you can all use the changes without the noise of each person’s individual activities. You unblock others, whilst also making merging easier in the future.

This also relates to branching; they’re closely linked.

When to branch

In most cases branching will be mandated by the environment you work in, and the tools you’ll be using. For example, GitHub uses branches to encapsulate changes in a pull request. You can prevent changes to the master or develop branches to ensure each change (group of commits on a branch) goes through a review process (the pull request).

I have not come across any scenario where creating a branch causes a problem. On the contrary, I’ve come across problems when branches haven’t been used.

Let’s break it down, a branch (aka a feature branch) is designed to encapsulate a group of changes. These changes might be thrown away, entirely rewritten or in the majority of cases they’ll be promoted into the main history of the codebase - via a merge.

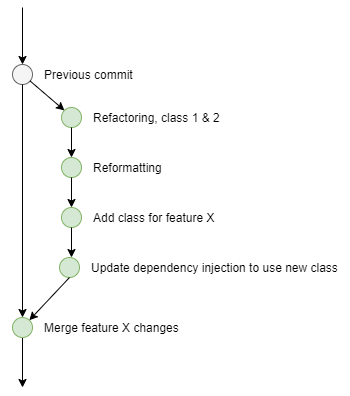

There is value in knowing what changes are contained in each branch and when it was promoted into the codebase. I’ve said before that it is extremely rare for a branch to contain one commit (unless you’re not committing frequently enough). As such a branch will contain many changes. These can be visualised in any source control history tool. They do a pretty good job of depicting when the branch was created and when it was merged, giving you the ability to see the set of commits (changes).

If you don’t branch, you lose all of this capability. Each set of changes appear in the otherwise un-augmented history view. After the event it is nigh-on impossible to detect when a set of changes started or was finished.

As a side note, remember the above points when merging branches. You should - in my opinion - always merge a branch into where you eventually want it, never rebase it. You’ll lose all of the branch information, just as if you committed all the changes directly onto the target branch.

Ok, rant over 🙄

Generally create a branch for every feature you’re working on. Commit all your changes there. Then when you’re done, merge it (pull request or not) to wherever it needs to go.

Simples 😀

Now what about that scenario I talked about earlier. Remember, there are a few of you all working on a feature. Each of you need a single change, so how do save having to repeat the work? Simple…

Create a branch, make your shared refactoring changes there. Keep the branch, you don’t need to merge it yet. Don’t forget this is your feature branch.

Now you and the others working on their own discrete features can branch off this branch for their individual tasks. Each branch can have nice small discrete commits pushed to it. Then when the task is complete, merge it back to the shared branch.

If you find more shared changes you all need, commit them to the shared branch. When all of you have finished and merged your changes to the shared branch, merge it wherever it needs to go.

One last thing. There is nothing more time consuming and troublesome than having to maintain a long lived feature branch. Merge the branch as soon as possible, or discard it. Of course if you make small commits some of them could be ‘cherry picked’ across if appropriate. But otherwise merge it or get rid. It takes so long and ultimately introduces risk and delays keeping them up to date.