While researching constraint-based minesweeper solvers, I discovered that many others had utilised SAT solvers in their algorithms. I had some exposure to SAT solvers in university, but this was the first time I saw them used in the wild. Around the same time, I was thinking back to a painful sprint planning meeting during our Scott Logic Grad Project. Could I use a SAT solver to improve our sprint planning meetings in future?

The full solver code is available on GitHub.

A what solver?

SAT solvers are programs which solve the boolean satisfiability problem (aka SAT). Since boolean satisfiability is NP-Complete, a SAT solver can be used to solve almost anything. In the worst case, they still take exponential time, but they are surprisingly fast for everyday use.

To apply a SAT solver to a real-life problem, we need to translate it into a form our solver can understand. SAT problems come in the form:

- Set each variable

{a,b,c}to0or1such that:a = 1orc = 1a = 0orb = 0orc = 0b = 0orc = 1

There are many solvers available online, but I chose the SAT4J Java library. It provides two extra features that were invaluable:

- Pseudo-boolean constraints let you add constraints in the form

Xa + Yb + Zc is at least/at most/exactly Kfor given integers{K,X,Y,Z}. - Weighted MAX-SAT computes the ‘value’ of each solution and picks the one with highest value. The value is computed using a function of the form

Ra + Sb + Tcgiven nonnegative integers{R,S,T}.

Applying MAX-SAT to sprint planning

In Scrum, sprint planning meetings involve deciding which work from the product backlog to perform in the next sprint. The development team estimates the amount of work required for each user story. The Product Owner decides which user stories are highest priority based on the amount of value delivered to the client. They work together to decide how to maximise the amount of value created in the sprint.

It can be difficult to translate problems into MAX-SAT, but this one seems trivial:

- Create a variable for each user story. If a variable is set to

1, it is included in the next sprint - Estimate the work of each story

e(x), in Story Points - Estimate the value of each story

v(x), in ‘Value Points’ - Constrain the total amount of work to be no more than the story point budget. This is a pseudo-boolean constraint in the form

e(a)*a + e(b)*b + ... <= budget - Maximise the function

v(a)*a + v(b)*b + ...

Value Points (which I just made up) and Story Points are arbitrary scales and each team can decide how to use them. The only requirement is proportionality - on either scale, three 1 point tasks should equal one 3 point task.

Reality is complicated

For the rest of the article, I’ll be referring to a real (slightly adjusted) sprint planning meeting. We had 5 user stories:

- As a user, I want to be able to log in and read posts

- As a user, I want to be able to sign up

- As an author, I want my name to appear on all my posts

- As an author, I want to be able to delete my posts

- As an admin, I want to be able to register authors

Deciding e(x) for each of these stories was easy at first:

The login task is quite big because we’ll need an authentication framework, let’s call it a 3

The sign-up task is even bigger than that! The UX alone makes it into a 5

Wait… it’s only a 5 if we haven’t done login yet - otherwise it’s only a 3

In the end, the real estimates looked like this, where the final cost depended on which other tasks were in the sprint:

User Login: 1-3User Signup: 3-5Author Names: 1-6Author Delete: 2-7Register Authors: 2-6

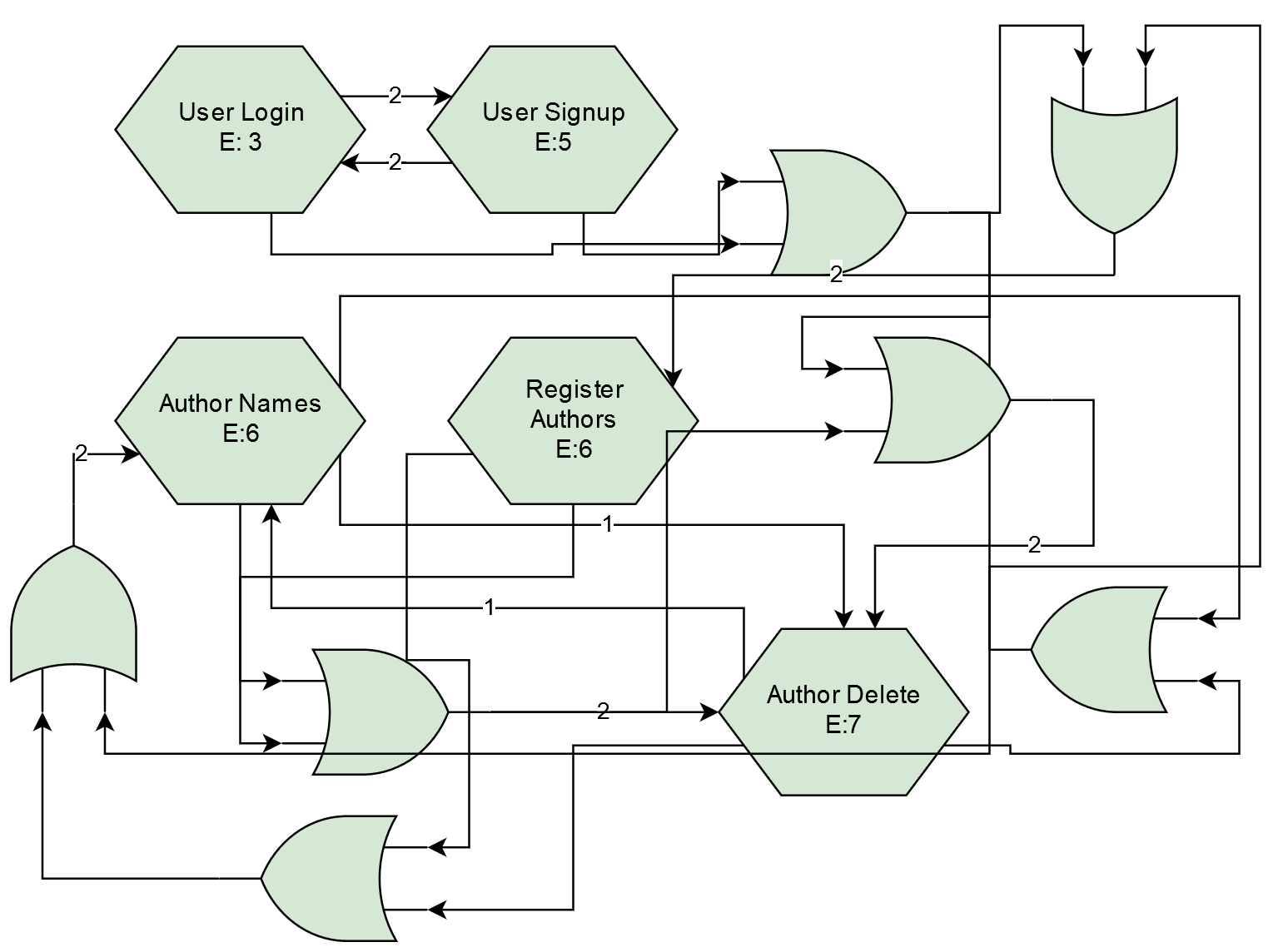

I was going to include the full list of dependencies, but it was too long. Instead, I created a dependency graph for you, which will make it much clearer:

…Nope.

If the development team can’t decide a single number for each user story, we can’t program our solver. It’s useless!

Circular Dependencies

The dependencies between our stories are circular. They’re not hard dependencies, but they affect the estimate for the task. That makes it impossible to give a single estimate for a given task, as we don’t know what other work will be in the sprint.

The real issue is that we’re being implicit about the tech tasks. These tasks don’t provide value to the user, but user stories depend on them being done, and they still take effort. For example, the login and signup stories both depend on an authentication framework being added.

Solving the problem

We need to separate tasks into two categories: tech and story. Tech tasks don’t directly provide any value to the client, so they should only be completed to unblock a user story. This means that all our soft dependencies become hard dependencies. However, it also breaks the circular dependencies, solving our issue.

In the case of login and signup, you end up with this:

- (Tech)

Framework: 2 - (Story)

Login: 1 (requiresFramework) - (Story)

Signup: 3 (requiresFramework)

The total cost of Login is 3, as before.

In the process of completing Login, we completed Framework, meaning Signup is unblocked and will only cost 3.

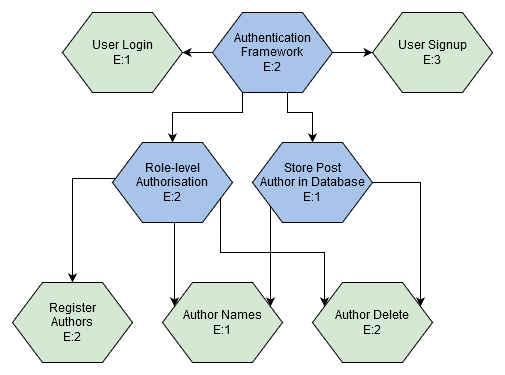

After extracting any tech tasks, and asking the PO to estimate the value of each user story, our final task list looks like this:

| ID | Task | Estimate | Value | Requires |

| a | Auth Framework | 2 | 0 | |

| b | User Login | 1 | 3 | a |

| c | User Signup | 3 | 1 | a |

| d | Role-Level Auth | 2 | 0 | a |

| e | Store Author | 1 | 0 | a |

| f | Register Authors | 2 | 1 | d |

| g | Author Names | 1 | 2 | d e |

| h | Author Delete | 2 | 2 | d e |

When graphing the dependencies, you can see that the situation is much simpler:

Updating the solver

Our first version of the solver didn’t handle blocked tasks, and we assumed that any task could be chosen regardless of the other tasks in the sprint. We need to stop the solver from creating sprints where we do tasks without their dependencies.

In mathematical terms, if we have tasks a and b, where b depends on a, we can say b implies a.

If b is included in the sprint, we know that a must also be included to satisfy the b’s dependency on a.

This is the same as (a and b) or (not b), which simplifies to a or not b.

Thankfully, a or not b is a constraint that our SAT solver can understand!

For each dependency, we can add that constraint.

For the backlog described previously, our final SAT problem is:

- Given variables

{a,b,...,h} - Maximise

3a + c + f + 2g + 2hsuch that:2a + b + 3c + 2d + e + 2f + g + 2h <= budgeta || !b,a || !c,a || !d,a || !ed || !f,d || !g,d || !he || !g,e || !h

Is it useful?

It could be. It’s not going to replace your Product Owner, but there’s a lot of benefits:

- Guaranteed to find the optimal solution

- Very fast, taking a few milliseconds for our tasks

- Allows for quick experimentation:

- If we budget 8 points, we only use 7. What if we commit to 9 points?

- What happens if we estimate this story as a 3?

- The client suddenly values task

cas a 3. What should change in the sprint?

We can even run the solver for all possible budgets to quickly see the options. The total time to run 14 instances of the problem was 250ms. That time includes set-up and outputting a table similar to this one:

| Budget | b |

c |

f |

g |

h |

Cost | Value |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 3 | ✔ | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | ✔ | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 5 | ✔ | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 6 | ✔ | ✔ | 6 | 4 | |||

| 7 | ✔ | ✔ | 7 | 5 | |||

| 8 | ✔ | ✔ | 7 | 5 | |||

| 9 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 9 | 7 | ||

| 10 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 9 | 7 | ||

| 11 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 11 | 8 | |

| 12 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 12 | 8 | |

| 13 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 12 | 8 | |

| 14 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 14 | 9 |

However, it’s not all good. Our solver doesn’t help with the hardest part of sprint planning - estimating the size and value of each task. Additionally, the sprints it creates aren’t very cohesive. They are more like a collection of unrelated tasks. When all the tasks in a sprint work towards a single sprint goal, developers can better support each other, and clients can give more relevant feedback.

This issue is like the circular dependencies we saw before. Tasks provide more value when other similar tasks are also included in the sprint. However, our solver does not support a dynamic value function, so we’ll just have to keep using humans for now.

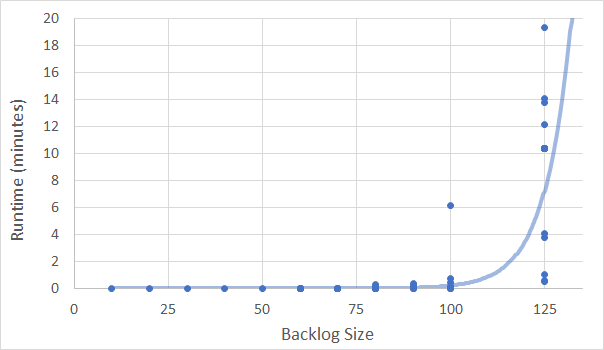

Also, it’s important to remember that SAT has exponential time complexity. As we add more tasks, it gets slow. Very slow:

It might be best to keep your backlog small. If we extrapolate to 300 tasks on the backlog, we get a predicted runtime of 600,000 years. Your sprint will probably be done by then…

Conclusion

Your Sprint Planning meetings are still valuable, and so is your Product Owner. You should probably keep both. However, there are still a few lessons we can learn:

- SAT solvers are useful and surprisingly easy to use

- The ‘optimal’ sprint might not be the best one

- Exponential time is still exponential, even when it’s fast